Tewksbury Hospital

|

Tewksbury State Hospital | |

| |

|

Old Administration Building | |

| |

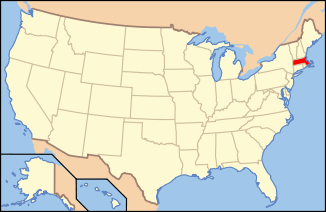

| Location | Tewksbury, Massachusetts |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 42°36′29.5986″N 71°13′3.4608″W / 42.608221833°N 71.217628000°WCoordinates: 42°36′29.5986″N 71°13′3.4608″W / 42.608221833°N 71.217628000°W |

| Built | 1854 |

| MPS | Massachusetts State Hospitals And State Schools MPS |

| NRHP Reference # | 93001486 [1] |

| Added to NRHP | January 21, 1994 |

Tewksbury Hospital, originally founded in 1854 as state almshouse,[2] is a National Register of Historic Places-listed site located in Tewksbury, MA on an 800+ acre campus.[3] The centerpiece of the hospital campus is the 1894 Richard Morris Building ("Old Administration Building").[4]

The Massachusetts Department of Public Health currently operates a Joint Commission accredited, 350-bed facility at Tewksbury Hospital, providing both medical and psychiatric services to challenging adult patients with chronic conditions.[5] The Public Health Museum in Massachusetts now occupies the Richard Morris Building.[6] In addition to the hospital and museum, the Tewksbury Hospital campus also hosts eight residential substance abuse programs, serving up to 275 patients. Five Massachusetts state agencies also have regional offices at Tewksbury, including the Massachusetts Department of Mental Health and the Massachusetts Department of Public Safety.[5] The campus also hosts several non-profit and for-profit private entities, including the Lahey Health Behavorial Services' Tewksbury Treatment Center,[7] the Lowell House's Sheehan Women's Program,[8] the Middlesex Human Service Agency,[9] and the Strongwater Farm Therapeutic Equestrian Center.[10]

History

Almshouse

Authorized by an act of Massachusetts General Court in 1852, Tewksbury Hospital was originally established as an Tewksbury Almshouse (along with similar facilities in Monson and Bridgewater), opening in May of 1854.[11] The original Tewksbury campus consisted of "large wooden buildings [which] were badly designed, poorly constructed firetraps".[2] Upon opening, paupers from across the state were sent to Tewksbury and its two companion facilities, rapidly overwhelming the facilities. Within three weeks, Tewksbury had a population of over 800, well over its intended capacity of 500. By the end of 1854, a total of 2,193 people had been admitted.[2]

By the mid-1860s formal record-keeping had began at Tewksbury, a series of intake records known as "inmate biographies". Based on these documents, historian and sociologist David Wagner estimates that one-third of the original population were children, and of the remaining adult population, 64% were male. The overwhelming majority of inmates were immigrants, mostly from Ireland. Tewksbury's demographics changed over time, with the number of children declining to only 10% by 1890.[12]

Almshouse to hospital

In 1866, a hospital was added to supplement the existing almshouse.[13] In that same year, Tewksbury first began accepting what were known as the "pauper insane".[6] In 1879, Tewksbury was reorganized, and its population separated according to type of illness: 40% of the beds were given over to the mentally ill; 33% to almshouse inmates, and 27% to hospital patients. By the end of the 1880s, Tewksbury had become solely a hospital, serving a combination of mentally and physically ill.[13] And by the 1890s, the original 1854 wooden almshouse building had been torn down, and the remaining almshouse buildings were repurposed for hospital use. Some of these would remain standing until the 1970s.[14]

Anne Sullivan

From February 1876 to October 1880, Tewksbury housed its most famous inmate, Anne Sullivan, best known as the teacher and companion of Helen Keller. Her mother dead, and abandoned by her father, Sullivan was admitted to Tewksbury at the age of ten, along with her younger brother Jimmie. Sullivan was afflicted with trachoma, which was beginning to blind her;[15] her brother was suffering from tuberculosis, which was to cause his death four months later.[14] Sullivan later recalled her time at Tewksbury:

Very much of what I remember about Tewksbury is indecent, cruel, melancholy, gruesome in the light of grown-up experience; but nothing corresponding with my present understanding of these ideas entered my child mind. Everything interested me. I was not shocked, pained, grieved or troubled by what happened. Such things happened. People behaved like that—that was all that there was to it. It was all the life I knew. Things impressed themselves upon me because I had a receptive mind. Curiosity kept me alert and keen to know everything.[16]

In October 1880, Sullivan left Tewksbury, allowed by the intervention of a state official to transfer to the Perkins School for the Blind in Boston.[15] A building at Tewksbury (the old Male Asylum building) is now named for her.[14]

The Butler committee

In 1883, Massachusetts Governor Benjamin F. Butler made headlines when he accused Tewksbury management and staff of variety of abuses ranging from the venal, "financial malfeasance, nepotism, patient abuse, and theft of inmate clothing and monies",[12] to the macabre, including "trading in bodies of dead paupers and transporting them for a profit to medical schools" and "tanned human flesh converted to shoes or other objects [...] from Tewksbury paupers".[12] The General Court (state legislature) organized a committee to investigate Tewksbury,[17] and political factions (and newspapers aligned with them) seized upon the story, either highlighting the most lurid parts of the testimony, or denouncing Butler as a liar using false allegations for political gain.[12]

Ultimately, the General Court rejected most of Butler's charges, but the publicity of the investigation led to new management and major changes at Tewksbury nonetheless.[12] Butler later wrote in his memoirs that the "investigation was productive of great good because it called the attention of the whole people of the country in the several States to the condition of things in institutions, and investigations of like character into their affairs in the succeeding year were quite general and caused great reforms."[18]

Construction and expansion

From 1894 to 1905, the Tewksbury campus saw extensive new construction, including several buildings designed by Boston architect John A. Fox—the Old Administration Building (1894), the Male Asylum (1901), the Womens' Asylum (1903).[14] During that period, the Old Superintendent's House (1894), the Chapel (1896), the Main Gate (1900), the Southgate Men's Building (1905), and Male Officers Dormitory (1905) were also added to Tewksbury, along with several farm and support buildings. [14]

The architectural history and quality of the Tewksbury campus was a key criteria for its inclusion on the National Register of Historic Places. The Massachusetts Historical Commission describes the Tewksbury's historic buildings as "designed in a variety of popular period styles such as Queen Anne, Romanesque Revival, Craftsman, Colonial Revival, and Classical Revival" and "generally unified by two-to-four story height, similar moderate scale, fieldstone foundations and redbrick walls, and overhanging slate hip or gable roofs with exposed rafters".[14]

Hospital

Reflecting it's changing mission, the Massachusetts General Court renamed Tewksbury Almshouse to Tewksbury State Hospital in 1900.[11] Tewksbury was to be renamed three times over the next century: to Tewksbury State Infirmary in 1909, to Tewksbury State Hospital and Infirmary in 1939, and finally to Tewksbury Hospital in 1959, the name it still bears.[19]

Nursing School

A Home Training School for Nurses opened at Tewksbury in 1894, and four years later was expanded to a complete three year training program.[6] Because of the variety of physical and mental conditions treated at Tewksbury, it was considered an ideal place for education of nurses. Author and reformer, Franklin Benjamin Sanborn, observed at the 1902 National Conference of Charities and Corrections:

[Tewksbury] has been obliged to receive all kinds for the thirty-eight years that I have known it, has received every disease which ever appeared in Massachusetts, not excepting leprosy; for we have had several cases of leprosy there. If you will consider what that signifies to the medical profession and the training of nurses, you will see how important it is that their training should go on where no disease is excluded.[20]

In 1921, a School of Practical Nursing was added at Tewksbury,[14] and trained nurses until its closure in 1997.[21]

-

State Hospital At Tewksbury, 1908

-

West Ward, Men's Hospital, c. 1900

-

Sun Room, Female Hospital, c. 1892

-

Kitchen & Dining Hall, c. 1903

-

Men's Dining Hall, c. 1903

-

Male Employees Building

See also

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Middlesex County, Massachusetts

- Tewksbury, Massachusetts

References

- ↑ Staff (2007-01-23). "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service.

- 1 2 3 Meltsner, Heli (March 27, 2012). The Poorhouses of Massachusetts: A Cultural and Architectural History. McFarland. p. 32–33. ISBN 9780786490974. Retrieved 21 January 2016.

- ↑ Town of Tewksbury, Affordable Housing Production Plan, 2012-2016 (PDF). Northern Middlesex Council of Governments. June 2012. p. 40-41. Retrieved 21 January 2016.

- ↑ Feely, Paul (February 15, 2013). "Public Health Museum opens in Tewksbury after extensive renovations". Tewksbury Town Crier. Retrieved 21 January 2016.

- 1 2 "Tewksbury Hospital". Executive Office of Health and Human Services. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- 1 2 3 "Our History". Public Health Museum in Massachusetts. 20 January 2016. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ↑ "Tewksbury Treatment Center" (PDF). Lahey Health. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ↑ "Sheehan Women's Program". Lowell House. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ↑ "Driving Under the Influence of Liquor Program". Middlesex Human Service Agency. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ↑ "Strongwater Farm–About Us". Strongwater Farm. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- 1 2 "Tewksbury Hospital (Mass.)". Social Networks and Archival Context (SNAC). Institute for Advanced Technology in the Humanities. Retrieved 25 January 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Wagner, David (November 30, 2015). Ordinary People: In and Out of Poverty in the Gilded Age. New York City: Routledge. pp. 31–43. ISBN 9781317254942. Retrieved 24 January 2016.

- 1 2 Baxter, William E.; Hathcox, David W. (1994). America's Care of the Mentally Ill: A Photographic History, Volume 1. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association Publishing. p. 56. ISBN 9780880485395. Retrieved 24 January 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Jenkins, Candace (8 December 1993). "National Register of Historic Places Registration Form: Tewksbury State Hospital". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. Retrieved 26 January 2015.

- 1 2 "Anne Sullivan Macy: Miracle Worker, Biography". American Foundation for the Blind. 2009. Retrieved 27 January 2016.

- ↑ "Anne Sullivan Macy: Miracle Worker, Anne's Formative Years (1866-1886)". American Foundation for the Blind. 2009. Retrieved 27 January 2016.

- ↑ "Gov. Butler's Charges Against The Tewksbury Almshouse Management". Disability History Museum. Retrieved 27 January 2016.

- ↑ Butler, Benjamin F. (1892). Butler's Book: Autobiography and Personal Reminiscences of Major-General Benj. F. Butler. Boston, MA: A.M. Thayer & Co., Book Publishers. p. 969. Retrieved 27 January 2016.

- ↑ "Tewksbury Hospital, DPH Medical Units and Hathorne Mental Health Units, Predoctoral Internship in Clinical Psychology". Tewksbury Hospital, Departments of Public and Mental Health. 2014. Retrieved 8 February 2016.

- ↑ Sanborn, F.B. (1902). "Discussion on Almshouse Hospitals". In Isabel C. Barrows. Proceedings of the National Conference of Charities and Correction. National Conference of Charities and Corrections. Boston MA: Geo. H. Ellis Co. p. 525. Retrieved 31 January 2016.

- ↑ Lannan, Katie (19 April 2014). "Classes long over, the caring goes on". Lowell Sun. Retrieved 8 February 2016.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||