Frame fields in general relativity

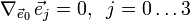

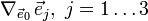

In general relativity, a frame field (also called a tetrad or vierbein) is a set of four orthonormal vector fields, one timelike and three spacelike, defined on a Lorentzian manifold that is physically interpreted as a model of spacetime. The timelike unit vector field is often denoted by  and the three spacelike unit vector fields by

and the three spacelike unit vector fields by  . All tensorial quantities defined on the manifold can be expressed using the frame field and its dual coframe field.

. All tensorial quantities defined on the manifold can be expressed using the frame field and its dual coframe field.

Frames were introduced into general relativity by Hermann Weyl in 1929.[1]

The general theory of tetrads (and analogs in dimensions other than 4) is described in the article on Cartan formalism; the index notation for tetrads is explained in tetrad (index notation).

Physical interpretation

Frame fields always correspond to a family of ideal observers immersed in the given spacetime; the integral curves of the timelike unit vector field are the worldlines of these observers, and at each event along a given worldline, the three spacelike unit vector fields specify the spatial triad carried by the observer. The triad may be thought of as defining the spatial coordinate axes of a local laboratory frame, which is valid very near the observer's worldline.

In general, the worldlines of these observers need not be timelike geodesics. If any of the worldlines bends away from a geodesic path in some region, we can think of the observers as test particles that accelerate by using ideal rocket engines with a thrust equal to the magnitude of their acceleration vector. Alternatively, if our observer is attached to a bit of matter in a ball of fluid in hydrostatic equilibrium, this bit of matter will in general be accelerated outward by the net effect of pressure holding up the fluid ball against the attraction of its own gravity. Other possibilities include an observer attached to a free charged test particle in an electrovacuum solution, which will of course be accelerated by the Lorentz force, or an observer attached to a spinning test particle, which may be accelerated by a spin–spin force.

It is important to recognize that frames are geometric objects. That is, vector fields make sense (in a smooth manifold) independently of choice of a coordinate chart, and (in a Lorentzian manifold), so do the notions of orthogonality and length. Thus, just like vector fields and other geometric quantities, frame fields can be represented in various coordinate charts. But computations of the components of tensorial quantities, with respect to a given frame, will always yield the same result, whichever coordinate chart is used to represent the frame.

These fields are required to write the Dirac equation in curved spacetime.

Specifying a frame

To write down a frame, a coordinate chart on the Lorentzian manifold needs to be chosen. Then, every vector field on the manifold can be written down as a linear combination of the four coordinate basis vector fields:

(Here, the Einstein summation convention is used, and the vector fields are thought of as first order linear differential operators, and the components  are often called contravariant components.) In particular, the vector fields in the frame can be expressed this way:

are often called contravariant components.) In particular, the vector fields in the frame can be expressed this way:

In "designing" a frame, one naturally needs to ensure, using the given metric, that the four vector fields are everywhere orthonormal.

Once a signature is adopted (in the case of a four-dimensional Lorentzian manifold, the signature is −1 + 3), by duality every vector of a basis has a dual covector in the cobasis and conversely. Thus, every frame field is associated with a unique coframe field, and vice versa.

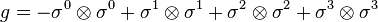

Specifying the metric using a coframe

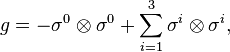

Alternatively, the metric tensor can be specified by writing down a coframe in terms of a coordinate basis and stipulating that the metric tensor is given by

where  denotes tensor product.

This is just a fancy way of saying that the coframe is orthonormal. Whether this is used to obtain the metric tensor after writing down the frame (and passing to the dual coframe), or starting with the metric tensor and using it to verify that a frame has been obtained by other means, it must always hold true.

denotes tensor product.

This is just a fancy way of saying that the coframe is orthonormal. Whether this is used to obtain the metric tensor after writing down the frame (and passing to the dual coframe), or starting with the metric tensor and using it to verify that a frame has been obtained by other means, it must always hold true.

Relationship with metric tensor, in a coordinate basis

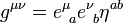

The vierbein field,  , has two kinds of indices:

, has two kinds of indices:  labels the general spacetime coordinate and

labels the general spacetime coordinate and  labels the local lorentz spacetime or local laboratory coordinates.

labels the local lorentz spacetime or local laboratory coordinates.

The vierbein field or frame fields can be regarded as the square root of the metric tensor,  , since in a coordinate basis,

, since in a coordinate basis,

where  is the Lorentz metric.

is the Lorentz metric.

Local lorentz indices are raised and lowered with the lorentz metric in the same way as general spacetime coordinates are raised and lowered with the metric tensor. For example:

The vierbein field enables conversion between spacetime and local lorentz indices. For example:

The vierbein field itself can be manipulated in the same fashion:

, since

, since

And these can combine.

A few more examples: Spacetime and local lorentz coordinates can be mixed together:

The local lorentz coordinates transform differently from the general spacetime coordinates. Under a general coordinate transformation we have:

whilst under a local lorentz transformation we have:

Comparison with coordinate basis

Coordinate basis vectors have the special property that their Lie brackets pairwise vanish. Except in locally flat regions, at least some Lie brackets of vector fields from a frame will not vanish. The resulting baggage needed to compute with them is acceptable, as components of tensorial objects with respect to a frame (but not with respect to a coordinate basis) have a direct interpretation in terms of measurements made by the family of ideal observers corresponding to the frame.

Coordinate basis vectors can very well be null, which, by definition, cannot happen for frame vectors.

Nonspinning and inertial frames

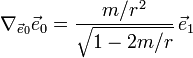

Some frames are nicer than others. Particularly in vacuum or electrovacuum solutions, the physical experience of inertial observers (who feel no forces) may be of particular interest. The mathematical characterization of an inertial frame is very simple: the integral curves of the timelike unit vector field must define a geodesic congruence, or in other words, its acceleration vector must vanish:

It is also often desirable to ensure that the spatial triad carried by each observer does not rotate. In this case, the triad can be viewed as being gyrostabilized. The criterion for a nonspinning inertial (NSI) frame is again very simple:

This says that as we move along the worldline of each observer, their spatial triad is parallel-transported. Nonspinning inertial frames hold a special place in general relativity, because they are as close as we can get in a curved Lorentzian manifold to the Lorentz frames used in special relativity (these are special nonspinning inertial frames in the Minkowski vacuum).

More generally, if the acceleration of our observers is nonzero,  , we can replace the covariant derivatives

, we can replace the covariant derivatives

with the (spatially projected) Fermi–Walker derivatives to define a nonspinning frame.

Given a Lorentzian manifold, we can find infinitely many frame fields, even if we require additional properties such as inertial motion. However, a given frame field might very well be defined on only part of the manifold.

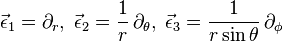

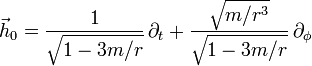

Example: Static observers in Schwarzschild vacuum

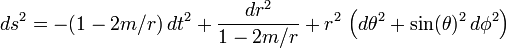

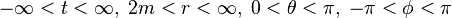

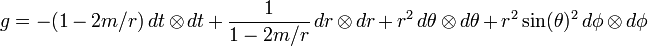

It will be instructive to consider in some detail a few simple examples. Consider the famous Schwarzschild vacuum that models spacetime outside an isolated nonspinning spherically symmetric massive object, such as a star. In most textbooks one finds the metric tensor written in terms of a static polar spherical chart, as follows:

More formally, the metric tensor can be expanded with respect to the coordinate cobasis as

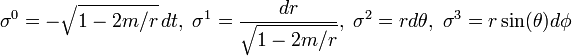

A coframe can be read off from this expression:

To see that this coframe really does correspond to the Schwarzschild metric tensor, just plug this coframe into

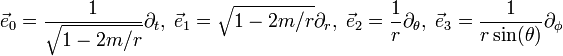

The frame dual to the coframe is

(The minus sign on  ensures that

ensures that  is future pointing.) This is the frame that models the experience of static observers who use rocket engines to "hover" over the massive object.

The thrust they require to maintain their position is given by the magnitude of the acceleration vector

is future pointing.) This is the frame that models the experience of static observers who use rocket engines to "hover" over the massive object.

The thrust they require to maintain their position is given by the magnitude of the acceleration vector

This is radially outward pointing, since the observers need to accelerate away from the object to avoid falling toward it. On the other hand, the spatially projected Fermi derivatives of the spatial basis vectors (with respect to  ) vanish, so this is a nonspinning frame.

) vanish, so this is a nonspinning frame.

The components of various tensorial quantities with respect to our frame and its dual coframe can now be computed.

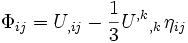

For example, the tidal tensor for our static observers is defined using tensor notation (for a coordinate basis) as

where we write  to avoid cluttering the notation. Its only non-zero components with respect to our coframe turn out to be

to avoid cluttering the notation. Its only non-zero components with respect to our coframe turn out to be

The corresponding coordinate basis components are

(A quick note concerning notation: many authors put carets over abstract indices referring to a frame. When writing down specific components, it is convenient to denote frame components by 0,1,2,3 and coordinate components by  . Since an expression like

. Since an expression like  doesn't make sense as a tensor equation, there should be no possibility of confusion.)

doesn't make sense as a tensor equation, there should be no possibility of confusion.)

Compare the tidal tensor  of Newtonian gravity, which is the traceless part of the Hessian of the gravitational potential

of Newtonian gravity, which is the traceless part of the Hessian of the gravitational potential  . Using tensor notation for a tensor field defined on three-dimensional euclidean space, this can be written

. Using tensor notation for a tensor field defined on three-dimensional euclidean space, this can be written

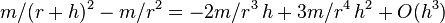

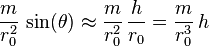

The reader may wish to crank this through (notice that the trace term actually vanishes identically when U is harmonic) and compare results with the following elementary approach: we can compare the gravitational forces on two nearby observers lying on the same radial line:

Because in discussing tensors we are dealing with multilinear algebra, we retain only first order terms, so  . Similarly, we can compare the gravitational force on two nearby observers lying on the same sphere

. Similarly, we can compare the gravitational force on two nearby observers lying on the same sphere  . Using some elementary trigonometry and the small angle approximation, we find that the force vectors differ by a vector tangent to the sphere which has magnitude

. Using some elementary trigonometry and the small angle approximation, we find that the force vectors differ by a vector tangent to the sphere which has magnitude

By using the small angle approximation, we have ignored all terms of order  , so the tangential components are

, so the tangential components are  . Here, we are referring to the obvious frame obtained from the polar spherical chart for our three-dimensional euclidean space:

. Here, we are referring to the obvious frame obtained from the polar spherical chart for our three-dimensional euclidean space:

Plainly, the coordinate components ![E[X]_{\theta \theta}, \, E[X]_{\phi \phi}](../I/m/1bb08ecb0754bb0a397136d39b5f206a.png) computed above don't even scale the right way, so they clearly cannot correspond to what an observer will measure even approximately. (By coincidence, the Newtonian tidal tensor components agree exactly with the relativistic tidal tensor components we wrote out above.)

computed above don't even scale the right way, so they clearly cannot correspond to what an observer will measure even approximately. (By coincidence, the Newtonian tidal tensor components agree exactly with the relativistic tidal tensor components we wrote out above.)

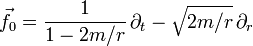

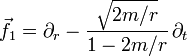

Example: Lemaître observers in the Schwarzschild vacuum

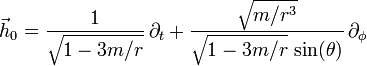

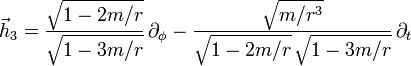

To find an inertial frame, we can boost our static frame in the  direction by an undetermined boost parameter (depending on the radial coordinate), compute the acceleration vector of the new undetermined frame, set this equal to zero, and solve for the unknown boost parameter. The result will be a frame which we can use to study the physical experience of observers who fall freely and radially toward the massive object. By appropriately choosing an integration constant, we obtain the frame of Lemaître observers, who fall in from rest at spatial infinity. (This phrase doesn't make sense, but the reader will no doubt have no difficulty in understanding our meaning.) In the static polar spherical chart, this frame can be written

direction by an undetermined boost parameter (depending on the radial coordinate), compute the acceleration vector of the new undetermined frame, set this equal to zero, and solve for the unknown boost parameter. The result will be a frame which we can use to study the physical experience of observers who fall freely and radially toward the massive object. By appropriately choosing an integration constant, we obtain the frame of Lemaître observers, who fall in from rest at spatial infinity. (This phrase doesn't make sense, but the reader will no doubt have no difficulty in understanding our meaning.) In the static polar spherical chart, this frame can be written

Note that

, and that

, and that  "leans inwards", as it should, since its integral curves are timelike geodesics representing the world lines of infalling observers. Indeed, since the covariant derivatives of all four basis vectors (taken with respect to

"leans inwards", as it should, since its integral curves are timelike geodesics representing the world lines of infalling observers. Indeed, since the covariant derivatives of all four basis vectors (taken with respect to  ) vanish identically, our new frame is a nonspinning inertial frame.

) vanish identically, our new frame is a nonspinning inertial frame.

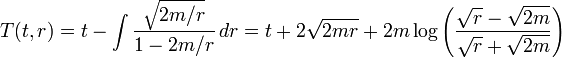

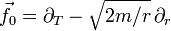

If our massive object is in fact a (nonrotating) black hole, we probably wish to follow the experience of the Lemaître observers as they fall through the event horizon at  . Since the static polar spherical coordinates have a coordinate singularity at the horizon, we'll need to switch to a more appropriate coordinate chart. The simplest possible choice is to define a new time coordinate by

. Since the static polar spherical coordinates have a coordinate singularity at the horizon, we'll need to switch to a more appropriate coordinate chart. The simplest possible choice is to define a new time coordinate by

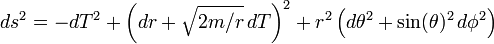

This gives the Painlevé chart. The new line element is

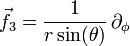

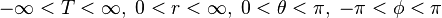

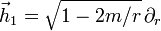

With respect to the Painlevé chart, the Lemaître frame is

Notice that their spatial triad looks exactly like the frame for three-dimensional euclidean space which we mentioned above (when we computed the Newtonian tidal tensor). Indeed, the spatial hyperslices  turn out to be locally isometric to flat three-dimensional euclidean space! (This is a remarkable and rather special property of the Schwarzschild vacuum; most spacetimes do not admit a slicing into flat spatial sections.)

turn out to be locally isometric to flat three-dimensional euclidean space! (This is a remarkable and rather special property of the Schwarzschild vacuum; most spacetimes do not admit a slicing into flat spatial sections.)

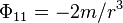

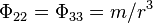

The tidal tensor taken with respect to the Lemaître observers is

where we write  to avoid cluttering the notation. This is a different tensor from the one we obtained above, because it is defined using a different family of observers. Nonetheless, its nonvanishing components look familiar:

to avoid cluttering the notation. This is a different tensor from the one we obtained above, because it is defined using a different family of observers. Nonetheless, its nonvanishing components look familiar: ![E[Y]_{11} = -2m/r^3, \, E[Y]_{22} = E[Y]_{33} = m/r^3](../I/m/00860a33e76826ab9493cc4c52bbf50e.png) . (This is again a rather special property of the Schwarzschild vacuum.)

. (This is again a rather special property of the Schwarzschild vacuum.)

Notice that there is simply no way of defining static observers on or inside the event horizon. On the other hand, the Lemaître observers are not defined on the entire exterior region covered by the static polar spherical chart either, so in these examples, neither the Lemaître frame nor the static frame are defined on the entire manifold.

Example: Hagihara observers in the Schwarzschild vacuum

In the same way that we found the Lemaître observers, we can boost our static frame in the  direction by an undetermined parameter (depending on the radial coordinate), compute the acceleration vector, and require that this vanish in the equatorial plane

direction by an undetermined parameter (depending on the radial coordinate), compute the acceleration vector, and require that this vanish in the equatorial plane  . The new Hagihara frame describes the physical experience of observers in stable circular orbits around our massive object. It was apparently first discussed by the astronomer Yusuke Hagihara.

. The new Hagihara frame describes the physical experience of observers in stable circular orbits around our massive object. It was apparently first discussed by the astronomer Yusuke Hagihara.

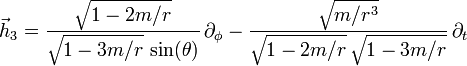

In the static polar spherical chart, the Hagihara frame is

which in the equatorial plane becomes

The tidal tensor ![E[Z]_{ab}](../I/m/482019acf72e0c31eadff46996eb26fa.png) where

where  turns out to be given (in the equatorial plane) by

turns out to be given (in the equatorial plane) by

Thus, compared to a static observer hovering at a given coordinate radius, a Hagihara observer in a stable circular orbit with the same coordinate radius will measure radial tidal forces which are slightly larger in magnitude, and transverse tidal forces which are no longer isotropic (but slightly larger orthogonal to the direction of motion).

Note that the Hagihara frame is only defined on the region  . Indeed, stable circular orbits only exist on

. Indeed, stable circular orbits only exist on  , so the frame should not be used inside this locus.

, so the frame should not be used inside this locus.

Computing Fermi derivatives shows that the frame field just given is in fact spinning with respect to a gyrostabilized frame. The principal reason why is easy to spot: in this frame, each Hagihara observer keeps his spatial vectors radially aligned, so  rotate about

rotate about  as the observer orbits around the central massive object. However, after correcting for this observation, a small precession of the spin axis of a gyroscope carried by a Hagihara observer still remains; this is the de Sitter precession effect (also called the geodetic precession effect).

as the observer orbits around the central massive object. However, after correcting for this observation, a small precession of the spin axis of a gyroscope carried by a Hagihara observer still remains; this is the de Sitter precession effect (also called the geodetic precession effect).

Generalizations

This article has focused on the application of frames to general relativity, and particularly on their physical interpretation. Here we very briefly outline the general concept. In an n-dimensional Riemannian manifold or pseudo-Riemannian manifold, a frame field is a set of orthonormal vector fields which forms a basis for the tangent space at each point in the manifold. This is possible globally in a continuous fashion if and only if the manifold is parallelizable. As before, frames can be specified in terms of a given coordinate basis, and in a non-flat region, some of their pairwise Lie brackets will fail to vanish.

In fact, given any inner-product space  , we can define a new space consisting of all tuples of orthonormal bases for

, we can define a new space consisting of all tuples of orthonormal bases for  . Applying this construction to each tangent space yields the orthonormal frame bundle of a (pseudo-)Riemannian manifold and a frame field is a section of this bundle. More generally still, we can consider frame bundles associated to any vector bundle, or even arbitrary principal fiber bundles. The notation becomes a bit more involved because it is harder to avoid distinguishing between indices referring to the base, and indices referring to the fiber. Many authors speak of internal components when referring to components indexed by the fiber.

. Applying this construction to each tangent space yields the orthonormal frame bundle of a (pseudo-)Riemannian manifold and a frame field is a section of this bundle. More generally still, we can consider frame bundles associated to any vector bundle, or even arbitrary principal fiber bundles. The notation becomes a bit more involved because it is harder to avoid distinguishing between indices referring to the base, and indices referring to the fiber. Many authors speak of internal components when referring to components indexed by the fiber.

See also

- Exact solutions in general relativity

- Georges Lemaître

- Karl Schwarzschild

- Method of moving frames

- Paul Painlevé

- Vierbein

- Yusuke Hagihara

References

- ↑ Hermann Weyl "Elektron und Gravitation I", Zeitschrift Physik, 56, p330–352, 1929.

- Flanders, Harley (1989). Differential Forms with Applications to the Physical Sciences. New York: Dover. ISBN 0-486-66169-5. See Chapter IV for frames in E3, then see Chapter VIII for frame fields in Riemannian manifolds. This book doesn't really cover Lorentzian manifolds, but with this background in hand the reader is well prepared for the next citation.

- Misner, Charles; Thorne, Kip S. & Wheeler, John Archibald (1973). Gravitation. San Francisco: W. H. Freeman. ISBN 0-7167-0344-0. In this book, a frame field (coframe field) is called an anholonomic basis of vectors (covectors). Essential information is widely scattered about, but can be easily found using the extensive index.

- Landau, L. D. & Lifschitz, E. F. (1980). The Classical Theory of Fields (4th ed.). London: Butterworth-Heinemann. ISBN 0-7506-2768-9. In this book, a frame field is called a tetrad (not to be confused with the now standard term NP tetrad used in the Newman–Penrose formalism). See Section 98.

- De Felice, F.; and Clarke, C. J. (1992). Relativity on Curved Manifolds. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-42908-0. See Chapter 4 for frames and coframes. If you ever need more information about frame fields, this might be a good place to look!

![E[X]_{ab} = R_{ambn} \, X^m \, X^n](../I/m/332e989add658a0cccd5fd3c584984bc.png)

![E[X]_{11} = -2m/r^3, \; E[X]_{22} = E[X]_{33} = m/r^3](../I/m/7d9bc473c4089dd8bb2fce43ba25e626.png)

![E[X]_{rr} = -2m/r^3/(1-2m/r), \; E[X]_{\theta \theta} = m/r, \; E[X]_{\phi \phi} = m \sin(\theta)^2/r](../I/m/6878330d8c0b93e6d4c10fbf13ac13e4.png)

![E[Y]_{ab} = R_{ambn} \, Y^m \, Y^n](../I/m/ae27b80b790915b7bc75215f66aac36b.png)

![E[Z]_{11} = -\frac{m}{r^3} \, \frac{2-3m/r}{1-2m/r} = -\frac{2m}{r^3} - \frac{m^2}{r^4} + O(1/r^5)](../I/m/e45706e0b4b4f14c1fb6c903a3c10ce0.png)

![E[Z]_{22} = \frac{m}{r^3} \, \frac{1}{1-3m/r} = -\frac{m}{r^3} + \frac{3m^2}{r^4} + O(1/r^5)](../I/m/d840b376f54f00a27bc902f3ed952c13.png)

![E[Z]_{33} = \frac{m}{r^3}](../I/m/9b8a42cf2c4795313d7c1d35daa7f63d.png)