Testicle

| Testicle | |

|---|---|

|

Inner workings of the testicles. | |

|

Diagram of male (human) testicles | |

| Details | |

| Artery | Testicular artery |

| Vein | Testicular vein, Pampiniform plexus |

| Nerve | Spermatic plexus |

| Lymph | Lumbar lymph nodes |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | testis |

| Dorlands /Elsevier | Testicle |

| TA | A09.3.01.001 |

| FMA | 7210 |

The testicle (from Latin testiculus, diminutive of testis, meaning "witness" of virility,[1] plural testes) is the male gonad in animals. Like the ovaries to which they are homologous, testes are components of both the reproductive system and the endocrine system. The primary functions of the testes are to produce sperm (spermatogenesis) and to produce androgens, primarily testosterone.

Both functions of the testicle are influenced by gonadotropic hormones produced by the anterior pituitary. Luteinizing hormone (LH) results in testosterone release. The presence of both testosterone and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) is needed to support spermatogenesis. It has also been shown in animal studies that if testes are exposed to either too high or too low levels of estrogens (such as estradiol; E2) spermatogenesis can be disrupted to such an extent that the animals become infertile.[2]

Structure

External appearance

Almost all healthy male vertebrates have two testicles. They are typically of similar size, although in sharks, that on the right side is usually larger, and in many bird and mammal species, the left may be the larger. The primitive jawless fish have only a single testis, located in the midline of the body, although even this forms from the fusion of paired structures in the embryo.[3]

The testicles of a dromedary camel are 7–10 cm (2.8–3.9 in) long, 4.5 cm (1.8 in) deep and 5 cm (2.0 in) in width. The right testicle is often smaller than the left.[4] The testicles of a male red fox attain their greatest weight in December–February.[5] Spermatogenesis in male golden jackals occurs 10–12 days before the females enter estrus and, during this time, males' testicles triple in weight.[6]

In mammals, the testes are often contained within an extension of the abdomen called the scrotum. In mammals with external testes it is most common for one testicle to hang lower than the other. While the size of the testicle varies, it is estimated that 21.9% of men have their higher testicle being their left, while 27.3% of men have reported to have equally positioned testicles.[7] This is due to differences in the vascular anatomical structure on the right and left sides.

In healthy European adult humans, average testicular volume is 18 cm³ per testis, with normal size ranging from 12 cm³ to 30 cm³.[8] The average testicle size after puberty measures up to around 2 inches long, 0.8 inches in breadth, and 1.2 inches in height (5 x 2 x 3 cm). Measurement in the living adult is done in two basic ways:

- comparing the testicle with ellipsoids of known sizes (orchidometer).

- measuring the length, depth and width with a ruler, a pair of calipers or ultrasound imaging.

The volume is then calculated using the formula for the volume of an ellipsoid: 4/3 π × (length/2) × (width/2) × (depth/2).

Human testicles are smaller than chimpanzee testicles but larger than gorilla testicles.[9]

The size of the testicles is among the parameters of the Tanner scale for the maturity of male genitals, from stage I which represents a volume of less than 1.5 ml, to stage V which represents a testicular volume of greater than 20 ml.

Internal structure

Duct system

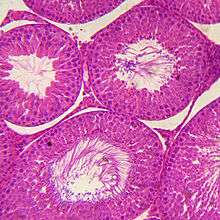

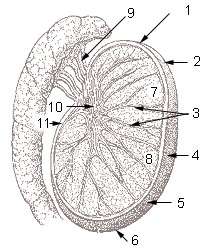

Under a tough membranous shell, the tunica albuginea, the testis of amniotes and some teleost fish, contains very fine coiled tubes called seminiferous tubules. The tubules are lined with a layer of cells (germ cells) that from puberty into old age, develop into sperm cells (also known as spermatozoa or male gametes). The developing sperm travel through the seminiferous tubules to the rete testis located in the mediastinum testis, to the efferent ducts, and then to the epididymis where newly created sperm cells mature (see spermatogenesis). The sperm move into the vas deferens, and are eventually expelled through the urethra and out of the urethral orifice through muscular contractions.

Amphibians and most fish do not possess seminiferous tubules. Instead, the sperm are produced in spherical structures called sperm ampullae. These are seasonal structures, releasing their contents during the breeding season, and then being reabsorbed by the body. Before the next breeding season, new sperm ampullae begin to form and ripen. The ampullae are otherwise essentially identical to the seminiferous tubules in higher vertebrates, including the same range of cell types.[3]

Primary cell types

- Within the seminiferous tubules

- Here, germ cells develop into spermatogonia, spermatocytes, spermatids and spermatozoon through the process of spermatogenesis. The gametes contain DNA for fertilization of an ovum[10]

- Sertoli cells – the true epithelium of the seminiferous epithelium, critical for the support of germ cell development into spermatozoa. Sertoli cells secrete inhibin.[11]

- Peritubular myoid cells surround the seminiferous tubules.[12]

- Between tubules (interstitial cells)

- Leydig cells – cells localized between seminiferous tubules that produce and secrete testosterone and other androgens important for sexual development and puberty, secondary sexual characteristics like facial hair, sexual behavior and libido, supporting spermatogenesis and erectile function. Testosterone also controls testicular volume.

- Also present are:

- Immature Leydig cells

- Interstitial macrophages and epithelial cells.

Blood supply and lymphatic drainage

Blood supply and lymphatic drainage of the testes and scrotum are distinct:

- The paired testicular arteries arise directly from the abdominal aorta and descend through the inguinal canal, while the scrotum and the rest of the external genitalia is supplied by the internal pudendal artery (itself a branch of the internal iliac artery).

- The testis has collateral blood supply from 1. the cremasteric artery (a branch of the inferior epigastric artery, which is a branch of the external iliac artery), and 2. the artery to the ductus deferens (a branch of the inferior vesical artery, which is a branch of the internal iliac artery). Therefore, if the testicular artery is ligated, e.g., during a Fowler-Stevens orchiopexy for a high undescended testis, the testis will usually survive on these other blood supplies.

- Lymphatic drainage of the testes follows the testicular arteries back to the paraaortic lymph nodes, while lymph from the scrotum drains to the inguinal lymph nodes.

Layers

Many anatomical features of the adult testis reflect its developmental origin in the abdomen. The layers of tissue enclosing each testicle are derived from the layers of the anterior abdominal wall. Notably, the cremasteric muscle arises from the internal oblique muscle.

The blood–testis barrier

Large molecules cannot pass from the blood into the lumen of a seminiferous tubule due to the presence of tight junctions between adjacent Sertoli cells. The spermatogonia are in the basal compartment (deep to the level of the tight junctions) and the more mature forms such as primary and secondary spermatocytes and spermatids are in the adluminal compartment.

The function of the blood–testis barrier (red highlight in diagram above) may be to prevent an auto-immune reaction. Mature sperm (and their antigens) arise long after immune tolerance is established in infancy. Therefore, since sperm are antigenically different from self tissue, a male animal can react immunologically to his own sperm. In fact, he is capable of making antibodies against them.

Injection of sperm antigens causes inflammation of the testis (auto-immune orchitis) and reduced fertility. Thus, the blood–testis barrier may reduce the likelihood that sperm proteins will induce an immune response, reducing fertility and so progeny.

Temperature regulation

The testes work best at temperatures slightly less than core body temperature. The spermatogenesis is less efficient at lower and higher temperatures. This is presumably why the testes are located outside the body. There are a number of mechanisms to maintain the testes at the optimum temperature.

Cremasteric muscle

The cremasteric muscle is part of the spermatic cord. When this muscle contracts, the cord is shortened and the testicle is moved closer up toward the body, which provides slightly more warmth to maintain optimal testicular temperature. When cooling is required, the cremasteric muscle relaxes and the testicle is lowered away from the warm body and is able to cool. It also occurs in response to stress (the testicles rise up toward the body in an effort to protect them in a fight). There are persistent reports that relaxation indicates approach of orgasm. There is a noticeable tendency to also retract during orgasm.

The cremaster muscle can reflexively raise each testicle individually if properly triggered. This phenomenon is known as the cremasteric reflex. The testicles can also be lifted voluntarily using the pubococcygeus muscle, which partially activates related muscles.

Development

There are two phases in which the testes grow substantially; namely in embryonic and pubertal age.

Embryonic

During mammalian development, the gonads are at first capable of becoming either ovaries or testes.[13] In humans, starting at about week 4 the gonadal rudiments are present within the intermediate mesoderm adjacent to the developing kidneys. At about week 6, sex cords develop within the forming testes. These are made up of early Sertoli cells that surround and nurture the germ cells that migrate into the gonads shortly before sex determination begins. In males, the sex-specific gene SRY that is found on the Y-chromosome initiates sex determination by downstream regulation of sex-determining factors, (such as GATA4, SOX9 and AMH), which leads to development of the male phenotype, including directing development of the early bipotential gonad down the male path of development.

Testes follow the "path of descent" from high in the posterior fetal abdomen to the inguinal ring and beyond to the inguinal canal and into the scrotum. In most cases (97% full-term, 70% preterm), both testes have descended by birth. In most other cases, only one testis fails to descend (cryptorchidism) and that will probably express itself within a year.

Pubertal

The testes grow in response to the start of spermatogenesis. Size depends on lytic function, sperm production (amount of spermatogenesis present in testis), interstitial fluid, and Sertoli cell fluid production. After puberty, the volume of the testes can be increased by over 500% as compared to the pre-pubertal size. Testicles are fully descended before one reaches puberty.

Evolution

External testes

The basal condition for mammals is to have internal testes. Boreoeutherian land mammals however, the large group of mammals that includes humans, have externalized testes. Their testes function best at temperatures lower than their core body temperature. Their testes are located outside of the body, suspended by the spermatic cord within the scrotum. The testes of the non-boreotherian mammals such as the monotremes, armadillos, sloths, elephants remain within the abdomen.[14] There are also some Boreoeutherian mammals with internal testes, such as the rhinoceros.

Marine boreotherian mammals, such as whales and dolphins, also have internal testes. As external testes would increase drag in the water they have internal testes which are kept cool by special circulatory systems that cool the arterial blood going to the testes by placing the arteries near veins bringing cooled venous blood from the skin.

There are several hypotheses why most boreotherian mammals have external testes which operate best at a temperature that is slightly less than the core body temperature, e.g. that it is stuck with enzymes evolved in a colder temperature due to external testes evolving for different reasons, that the lower temperature of the testes simply is more efficient for sperm production.

1) More efficient. The classic hypothesis is that cooler temperature of the testes allows for more efficient fertile spermatogenesis. In other words, there are no possible enzymes operating at normal core body temperature that are as efficient as the ones evolved, at least none appearing in our evolution so far.

The early mammals had lower body temperatures and thus their testes worked efficiently within their body. However it is argued that boreotherian mammals have higher body temperatures than the other mammals and had to develop external testes to keep them cool. It is argued that those mammals with internal testes, such as the monotremes, armadillos, sloths, elephants, and rhinoceroses, have a lower core body temperatures than those mammals with external testes.

However, the question remains why birds despite having very high core body temperatures have internal testes and did not evolve external testes.[15] It was once theorized that birds used their air sacs to cool the testes internally, but later studies revealed that birds' testes are able to function at core body temperature.[15]

Some mammals which have seasonal breeding cycles keep their testes internal until the breeding season at which point their testes descend and increase in size and become external.[16]

2) Irreversible adaptation to sperm competition. It has been suggested that the ancestor of the boreoeutherian mammals was a small mammal that required very large testes (perhaps rather like those of a hamster) for sperm competition and thus had to place its testes outside the body.[17] This led to enzymes involved in spermatogenesis, spermatogenic DNA polymerase beta and recombinase activities evolving a unique temperature optimum, slightly less than core body temperature. When the boreoeutherian mammals then diversified into forms that were larger and/or did not require intense sperm competition they still produced enzymes that operated best at cooler temperatures and had to keep their testes outside the body. This position is made less parsimonious by the fact that the kangaroo, a non-boreoeutherian mammal, has external testicles. The ancestors of kangaroos might, separately from boreotherian mammals, have also been subject to heavy sperm competition and thus developed external testes, however, kangaroo external testes are suggestive of a possible adaptive function for external testes in large animals.

3) Protection from abdominal cavity pressure changes. One argument for the evolution of external testes is that it protects the testes from abdominal cavity pressure changes caused by jumping and galloping.[18]

Testicular size

Testicular size as a proportion of body weight varies widely. In the mammalian kingdom, there is a tendency for testicular size to correspond with multiple mates (e.g., harems, polygamy). Production of testicular output sperm and spermatic fluid is also larger in polygamous animals, possibly a spermatogenic competition for survival. The testes of the right whale are likely to be the largest of any animal, each weighing around 500 kg (1,100 lb).[19]

Among the Hominidae, gorillas have little female promiscuity and sperm competition and the testes are small compared to body weight (0.03%). Chimpanzees have high promiscuity and large testes compared to body weight (0.3%). Human testicular size falls between these extremes (0.08%).[20]

There is some evidence to suggest that average human testicle size and weight has been progressively shrinking in recent years among younger cohorts in Western industrialized nations. This has been suggested to be associated with a possible decline in sperm counts in some world regions. The recent changes suggest involvement of environmental or lifestyle factor(s) such as increasing exposure to endocrine disruptors.[21]

Testis weight also varies in seasonal breeders like deer and horses. The change is related to changes in testosterone production.

Clinical significance

Protection and injury

- The testicles are well-known to be very sensitive to impact and injury. The pain involved travels up from each testicle into the abdominal cavity, via the spermatic plexus, which is the primary nerve of each testicle. This will cause pain in the hip and the back. The pain usually goes away in a few minutes.

- Testicular torsion is a medical emergency. Treatment within 4–6 hours of onset can prevent necrosis of the testis.[22]

- Testicular rupture is a medical emergency caused by blunt force impact, sharp edge, or piercing impact to one or both testicles, which can lead to necrosis of the testis in as little as 30 minutes.

- Penetrating injuries to the scrotum may cause castration, or physical separation or destruction of the testes, possibly along with part or all of the penis, which results in total sterility if the testicles are not reattached quickly.

- Some jockstraps are designed to provide support to the testicles.[23]

Diseases and conditions that affect the testes

Some prominent conditions and differential diagnoses include:

- Testicular cancer and other neoplasms To improve the chances of catching possible cases of testicular cancer or other health issues early, regular testicular self-examination is recommended.

- Varicocele, swollen vein(s) from the testes, usually affecting the left side,[24] the testis usually being normal

- Hydrocele testis, swelling around testes caused by accumulation of clear liquid within a membranous sac, the testis usually being normal

- Endocrine disorders can also affect the size and function of the testis.

- Certain inherited conditions involving mutations in key developmental genes also impair testicular descent, resulting in abdominal or inguinal testes which remain nonfunctional and may become cancerous. Other genetic conditions can result in the loss of the Wolffian ducts and allow for the persistence of Müllerian ducts.

- Bell-clapper deformity is a deformity in which the testicle is not attached to the scrotal walls, and can rotate freely on the spermatic cord within the tunica vaginalis. It is the most common underlying cause of testicular torsion.

- Epididymitis, a painful inflammation of the epididymis or epididymides frequently caused by bacterial infection but sometimes of unknown origin.

Effects of exogenous hormones

To some extent, it is possible to change testicular size. Short of direct injury or subjecting them to adverse conditions, e.g., higher temperature than they are normally accustomed to, they can be shrunk by competing against their intrinsic hormonal function through the use of externally administered steroidal hormones. Steroids taken for muscle enhancement (especially anabolic steroids) often have the undesired side effect of testicular shrinkage.

Similarly, stimulation of testicular functions via gonadotropic-like hormones may enlarge their size. Testes may shrink or atrophy during hormone replacement therapy or through chemical castration.

In all cases, the loss in testes volume corresponds with a loss of spermatogenesis.

Society and culture

Testicles of a male calf or other livestock are used to comprise a dish, sometimes called Rocky Mountain oysters.[25]

History

In the Middle Ages, men who wanted a boy sometimes had their left testicle removed. This was because people believed that the right testicle made "boy" sperm and the left made "girl" sperm.[26] As early as 330 BC, Aristotle prescribed the ligation (tying off) of the left testicle in men wishing to have boys.[27]

Etymology

The etymology of the word is based on Roman law. The Latin word "testis", witness, was used in the firmly established legal principle "Testis unus, testis nullus" (one witness [equals] no witness), meaning that testimony by any one person in court was to be disregarded unless corroborated by the testimony of at least another. This led to the common practice of producing two witnesses, bribed to testify the same way in cases of lawsuits with ulterior motives. Since such "witnesses" always came in pairs, the meaning was accordingly extended, often in the diminutive (testiculus, testiculi).

Another theory says that testis is influenced by a loan translation, from Greek parastatēs "defender (in law), supporter" that is "two glands side by side".[28]

Gallery

-

Testicle

-

Testicle

-

Hanging testicles.JPG

Testicle hanging on cremaster muscle. These are two healthy testicles. Heat causes them to descend, allowing cooling.

-

Human Scrotum.JPG

A healthy scrotum containing normal size testes. The scrotum is in tight condition. The image also shows the texture.

-

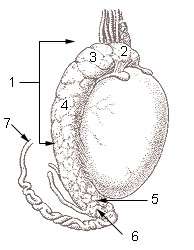

Testicle of a cat: 1: Extremitas capitata, 2: Extremitas caudata, 3: Margo epididymalis, 4: Margo liber, 5: Mesorchium, 6: Epididymis, 7: testicular artery and vene, 8: Ductus deferens

-

Testis surface

-

Testis cross section

-

The right testis, exposed by laying open the tunica vaginalis.

-

Microscopic view of Rabbit testis 100×

-

Testicle

See also

- Anorchia

- Castration

- Cryptorchidism (cryptorchismus)

- Eunuchs

- Gelding

- Neutering

- Polyorchidism

- Infertility

- List of homologues of the human reproductive system

- Orchidometer

- Spermatogenesis

- Sterilization (surgical procedure), vasectomy

- Testicondy

- Testosterone

- Epididymis

- Spermatic cord

- Penis

- Perineum

- Bollocks

- WikiSaurus:testicles — the WikiSaurus list of synonyms and slang words for testicles in many languages

- Ejaculation

Notes

- Heptner, V. G.; Naumov, N. P. (1998). Mammals of the Soviet Union Vol.II Part 1a, SIRENIA AND CARNIVORA (Sea cows; Wolves and Bears). Science Publishers, Inc. USA. ISBN 1-886106-81-9. Retrieved 2013-11-09.

- ↑ "Blackwell Synergy". Blackwell Synergy. Retrieved 2010-10-25.

- ↑ Sierens, J. E.; Sneddon, S. F.; Collins, F.; Millar, M. R.; Saunders, P. T. (2005). "Estrogens in Testis Biology". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1061: 65–76. doi:10.1196/annals.1336.008. PMID 16467258.

- 1 2 Romer, Alfred Sherwood; Parsons, Thomas S. (1977). The Vertebrate Body. Philadelphia, PA: Holt-Saunders International. pp. 385–386. ISBN 0-03-910284-X.

- ↑ Mukasa-Mugerwa, E. The Camel (Camelus dromedarius): A Bibliographical Review. pp. 11–3.

- ↑ Heptner & Naumov 1998, p. 537

- ↑ Heptner & Naumov 1998, pp. 154–155

- ↑ Scrotal Asymmetry: Right-Left and the scrotum in male sculpture"" By I. C. Manus

- ↑ Andrology: Male Reproductive Health and Dysfunction"" By E. Nieschlag, Hermann M. Behre, H. van. Ahlen

- ↑ Human Origins 101 – Page 138, Holly M. Dunsworth – 2007

- ↑ Histology, A Text and Atlas by Michael H. Ross and Wojciech Pawlina, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 5th ed, 2006

- ↑ Skinner M, McLachlan R, Bremner W (1989). "Stimulation of Sertoli cell inhibin secretion by the testicular paracrine factor PModS". Mol Cell Endocrinol 66 (2): 239–49. doi:10.1016/0303-7207(89)90036-1. PMID 2515083.

- ↑ Arch Histol Cytol. 1996 Mar;59(1):1–13

- ↑ Online textbook: "Developmental Biology" 6th ed. By Scott F. Gilbert (2000) published by Sinauer Associates, Inc. of Sunderland (MA).

- ↑ Spermatogenesis

- 1 2 BIOLOGY OF REPRODUCTION 56, 1570–1575 (1997)- Determination of Testis Temperature Rhythms and Effects of Constant Light on Testicular Function in the Domestic Fowl (Gallus domesticus)

- ↑ "Ask a Biologist Q&A / Human sexual physiology – good design?". Askabiologist.org.uk. 2007-09-04. Retrieved 2010-10-25.

- ↑ "'The Human Body as an Evolutionary Patchwork' by Alan Walker, Princeton.edu". RichardDawkins.net. 2007-04-10. Retrieved 2010-10-25.

- ↑ Newscientist.com – bumpy-lifestyle-led-to-external-testes

- ↑ Crane, J.; Scott, R. (2002). "Eubalaena glacialis". Animal Diversity Web. Retrieved 2009-05-01.

- ↑ Shackelford, T. K.; Goetz, A. T. (2007). "Adaptation to Sperm Competition in Humans". Current Directions in Psychological Science 16: 47. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8721.2007.00473.x.

- ↑ Dindyal, S. (2007). "The sperm count has been decreasing steadily for many years in Western industrialised countries: Is there an endocrine basis for this decrease?". The Internet Journal of Urology 2 (1): 1–21.

- ↑ S. Khan, J. Rehman, B. Chughtai, D. Sciullo, E. Mohan & H. Rehman: "Anatomical Approach to Scrotal Emergencies: A New Paradigm for the Diagnosis and Treatment of the Acute Scrotum". The Internet Journal of Urology. (2010) Volume 6: Number 2. ISSN 1528-8390.

- ↑ Amazon.com: Suspensory Jockstrap for Scrotal/Testicle Support: Health & Personal Care

- ↑ "Varicocele". Kidshealth.org. Retrieved 2010-10-25.

- ↑ Reviving a very delicate delicacy

- ↑ Understanding genetics; Human health and genome Stanford school of medicine, Dr. Barry Starr

- ↑ Hoag, Hannah. I'll take a girl, please... Cherry-picking from the dish of life. Drexel University Publication. Archived May 11, 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, Fourth Edition

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|