Reign of Terror

| 5 September 1793 – 28 July 1794 | |

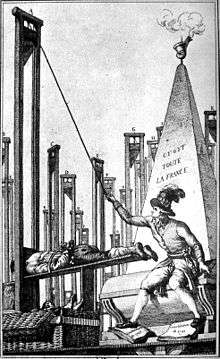

Nine emigrants are executed by guillotine, 1793 | |

| Preceded by | Montagnard Convention |

|---|---|

| Followed by | Thermidorian Reaction |

| Leader(s) | Louis Antoine de Saint-Just Maximilien Robespierre Bertrand Barère de Vieuzac Collot d'Herbois |

The Reign of Terror (5 September 1793 – 28 July 1794),[1] also known as The Terror (French: la Terreur), was a period of violence that occurred after the onset of the French Revolution, incited by conflict between two rival political factions, the Girondins and The Mountain, and marked by mass executions of "enemies of the revolution". The death toll ranged in the tens of thousands, with 16,594 executed by guillotine (2,639 in Paris),[2] and another 25,000 in summary executions across France.[3]

The guillotine (called the "National Razor") became the symbol of the revolutionary cause, strengthened by a string of executions: King Louis XVI, Marie Antoinette, the Girondins, Philippe Égalité (Louis Philippe II, Duke of Orléans), and Madame Roland, and others such as pioneering chemist Antoine Lavoisier, lost their lives under its blade. During 1794, revolutionary France was beset with conspiracies by internal and foreign enemies. Within France, the revolution was opposed by the French nobility, which had lost its inherited privileges. The Roman Catholic Church opposed the revolution, which had turned the clergy into employees of the state and required they take an oath of loyalty to the nation (through the Civil Constitution of the Clergy). In addition, the French First Republic was engaged in a series of wars with neighboring powers, and parts of France were engaging in civil war against the republican regime.

The extension of civil war and the advance of foreign armies on national territory produced a political crisis and increased the already present rivalry between the Girondins and the more radical Jacobins. The latter were eventually grouped in the parliamentary faction called the Mountain, and they had the support of the Parisian population. The French government established the Committee of Public Safety, which took its final form on 6 September 1793, in order to suppress internal counter-revolutionary activities and raise additional French military forces.

Through the Revolutionary Tribunal, the Terror's leaders exercised broad powers and used them to eliminate the internal and external enemies of the republic. The repression accelerated in June and July 1794, a period called la Grande Terreur (the Great Terror), and ended in the coup of 9 Thermidor Year II (27 July 1794), leading to the Thermidorian Reaction, in which several instigators of the Reign of Terror were executed, including Saint-Just and Robespierre.

Origins and causes

After the resolution of foreign wars during 1791–93, the violence associated with the Reign of Terror increased significantly: only roughly 4% of executions had occurred before November 1793 (Brumaire, Year I), thus signalling to many that the Reign of Terror might have had additional causes.[3] These could have included inherent issues with revolutionary ideology,[4] and/or the need of a weapon for political repression in a time of significant foreign and civil upheaval,[3] leading to many different interpretations by historians.

Many historians have debated the reasons the French Revolution took such a radical turn during the Reign of Terror of 1793–94. The public was frustrated that the social equality and anti-poverty measures that the revolution originally promised were not materializing. Jacques Roux's Manifesto of the Enraged on 25 June 1793, describes the extent to which, four years into the revolution, these goals were largely unattained by the common people.[5] The foundation of the Terror is centered on the April 1793 creation of the Committee of Public Safety and its militant Jacobin delegates. The National Convention believed that the committee needed to rule with "near dictatorial power" and the committee was delegated new and expansive political powers[6] to respond quickly to popular demands.[7]

Those in power believed the Committee of Public Safety was an unfortunate, but necessary and temporary, reaction to the pressures of foreign and civil war.[8] Historian Albert Mathiez argues that the authority of the Committee of Public Safety was based on the necessities of war, as those in power realized that deviating from the will of the people was a temporary emergency response measure in order to secure the ideals of the republic. According to Mathiez, they "touched only with trepidation and reluctance the regime established by the Constituent Assembly" so as not to interfere with the early accomplishments of the revolution.[9]

Similar to Mathiez, Richard Cobb introduced competing circumstances of revolt and re-education within France as an explanation for the Terror. Counter-revolutionary rebellions taking place in Lyon, Brittany, Vendée, Nantes, and Marseille were threatening the revolution with royalist ideas.[10] Cobb writes, "the revolutionaries themselves, living as if in combat… were easily persuaded that only terror and repressive force saved them from the blows of their enemies."[11]

Terror was used in these rebellions both to execute inciters and to provide a very visible example to those who might be considering rebellion. Cobb agrees with Mathiez that the Terror was simply a response to circumstances, a necessary evil and natural defence, rather than a manifestation of violent temperaments or excessive fervour. At the same time, Cobb rejects Mathiez's Marxist interpretation that elites controlled the Reign of Terror to the significant benefit to the bourgeoisie. Instead, Cobb argues that social struggles between the classes were seldom the reason for revolutionary actions and sentiments.[12]

Francois Furet, however, argues that circumstances could not have been the sole cause of the Reign of Terror because "the risks for the revolution were greatest" in the middle of 1793 but at that time "the activity of the Revolutionary Tribunal was relatively minimal."[13] Widespread terror and a consequent rise in executions came after external and internal threats were vastly reduced. Therefore, Furet suggests that ideology played the crucial role in the rise of the Reign of Terror because "man's regeneration" became a central theme for the Committee of Public Safety as they were trying to instill ideals of free will and enlightened government in the public.[14] As this ideology became more and more pervasive, violence became a significant method for dealing with counter-revolutionaries and the opposition because, for fear of being labelled a counter-revolutionary themselves, "the moderate men would have to accept, endorse and even glorify the acts of the more violent."[15]

The Terror

On 2 June 1793, Paris sections – encouraged by the enragés Jacques Roux and Jacques Hébert – took over the convention, calling for administrative and political purges, a low fixed price for bread, and a limitation of the electoral franchise to sans-culottes alone. With the backing of the national guard, they persuaded the convention to arrest 29 Girondist leaders, including Jacques Pierre Brissot.[16] On 13 July the assassination of Jean-Paul Marat – a Jacobin leader and journalist known for his violent rhetoric – by Charlotte Corday resulted in a further increase in Jacobin political influence.

Georges Danton, the leader of the August 1792 uprising against the king, was removed from the committee. On 27 July Maximilien Robespierre, known in Republican circles as "the Incorruptible" for his ascetic dedication to his ideals, made his entrance, quickly becoming the most influential member of the committee as it moved to take radical measures against the revolution's domestic and foreign enemies.

The Jacobins identified themselves with the popular movement and the sans-culottes, who in turn saw popular violence as a political right. The most notorious instance of the crowd's rough justice was the prison massacres of September 1792, when around 2,000 people, including priests and nuns, were dragged from their prison cells and subjected to summary 'justice'. The Convention was determined to avoid a repeat of these brutal scenes, but that meant taking violence into their own hands as an instrument of government.[17]

Meanwhile, on 24 June, the convention adopted the first republican constitution of France, the French Constitution of 1793. It was ratified by public referendum, but never put into force; like other laws, it was indefinitely suspended by the decree of October that the government of France would be "revolutionary until the peace".

On 25 December 1793, Robespierre stated:

The goal of the constitutional government is to conserve the republic; the aim of the revolutionary government is to found it... The revolutionary government owes to the good citizen all the protection of the nation; it owes nothing to the enemies of the people but death... These notions would be enough to explain the origin and the nature of laws that we call revolutionary ... If the revolutionary government must be more active in its march and more free in his movements than an ordinary government, is it for that less fair and legitimate? No; it is supported by the most holy of all laws: the salvation of the people.[18]

On 5 February 1794, Robespierre stated, more succinctly, that, "Terror is nothing else than justice, prompt, severe, inflexible."[19]

The government in a revolution is the despotism of liberty against tyranny.— Maximilien Robespierre, 1794[20]

Robespierre, a French lawyer, did not abandon his libertarian convictions, but he was coming to the conclusion that the ends justified the means, and that in order to defend the Revolution against those who would destroy it, the shedding of blood was justified. The enigmatic figure of Robespierre takes us to the heart of the Revolution and throws light on both its ideals and the violence that indelibly scarred it. Robespierre stated:

If the basis of popular government in peacetime is virtue, the basis of popular government during a revolution is both virtue and terror; virtue, without which terror is baneful; terror, without which virtue is powerless. Terror is nothing more than speedy, severe and inflexible justice; it is thus an emanation of virtue; it is less a principle in itself, than a consequence of the general principle of democracy, applied to the most pressing needs of the patrie.

In June 1793, the sans-culottes, exasperated by the inadequacies of the government, invaded the Convention and overthrew the Girondins. In their place they endorsed the political ascendancy of the Jacobins. Thus Robespierre came to power on the back of popular street violence.[17]

Six points

Led by Robespierre, the National Convention, in an attempt to make their stance known to the world over, released a statement of French Foreign policy. The following six points acted to further highlight the convention’s fear of enemies of the Revolution. Because of this fear, several other legislations passed which furthered the Jacobin domination of the Revolution. This led to the consolidation, extension, and application of emergency government devices in order to maintain what the Revolution considered ‘control’.[21]

The first point addressed stated:

The National Convention declares, in the name of the French people, that it firmly intends to be terrible towards its enemies, generous towards its allies, and just towards its peoples.

The result of this was policy through which the state used violent repression to crush resistance to the government. Under control of the effectively dictatorial committee, the convention quickly enacted more legislation. On 9 September, the convention established sans-culottes paramilitary forces, the "revolutionary armies", to force farmers to surrender grain demanded by the government. On 17 September, the Law of Suspects was passed, which authorized the charging of counter-revolutionaries with vaguely defined "crimes against liberty". On 29 September, the convention extended price-fixing from grain and bread to other essential goods, and also fixed wages. The guillotine became the symbol of a string of executions: Louis XVI had already been guillotined before the start of the terror; Marie Antoinette, the Girondists, Philippe Égalité, Madame Roland and many others lost their lives under its blade.

The second point, the passing of the Law of Suspects, stepped political terror up to a much higher level of cruelty. Anyone who ‘by their conduct, relations, words or writings show themselves to be supporters of tyranny and federalism and enemies of freedom’ was targeted and suspected of treason. This created a mass overflow in the prison systems. As a result, the prison population of Paris increased from 1,417 to 4,525 people over a course of 3 months. This overpopulation problem caused the execution rates to rise enormously. From March to September of 1789 sixty-six people had been guillotined. By the end of the year, that number had risen to 177.[22]

Though the Girondins and the Jacobins were both on the extreme left, and shared many of the same radical republican convictions, the Jacobins were more brutally efficient in setting up a war government. The year of Jacobin rule was the first time in history that terror became an official government policy, with the stated aim to use violence to achieve a higher political goal. The number of death sentences in Paris was 2,639, while the total number during the Terror in the whole of France (including Paris) was 16,594. The Jacobins were meticulous in maintaining a legal structure for the Terror so clear records exist for official death sentences. However, many more people were murdered without formal sentences proposed in a court of law.[17]

The Revolutionary Tribunal summarily condemned thousands of people to death by the guillotine, while mobs beat other victims to death. Sometimes people died for their political opinions or actions, but many for little reason beyond mere suspicion, or because some others had a stake in getting rid of them. The historian Peter Jones reminds the case of Claude-François Bertrand de Boucheporn, the last intendant of Béarn, whose “two sons had emigrated. [He] attracted mounting suspicion. Eventually, he was tried on a charge of sending money abroad and, in 1794, executed.” [23]

Among people who were condemned by the revolutionary tribunals, about 8% were aristocrats, 6% clergy, 14% middle class, and 72% were workers or peasants accused of hoarding, evading the draft, desertion, or rebellion.[24] Maximilien Robespierre, "frustrated with the progress of the revolution,"[25] saw politics through a populist lens because "any institution which does not suppose the people good, and the magistrate corruptible, is evil."[26]

Another anti-clerical uprising was also made possible by the enactment of the Revolutionary Calendar on 24 October. Hébert's and Chaumette's atheist movement initiated an anti-religious campaign in order to dechristianise society. The program of dechristianisation waged against Catholicism, and also eventually against all forms of Christianity, included the deportation or execution of clergymen and women; the closing of churches; the rise of cults and the institution of a civic religion; the large scale destruction of religious monuments; the outlawing of public and private worship and religious education; the forced abjuration of priests of their vows and forced marriages of the clergy; the word "saint" being removed from street names; and the War in the Vendée.[27]

The enactment of a law on 21 October 1793 made all suspected priests and all persons who harbored them liable to summary execution.[27] The climax was reached with the celebration of the goddess Reason in Notre Dame Cathedral on 10 November. Because dissent was now regarded as counter-revolutionary, extremist enragés such as Hébert and moderate Montagnard indulgents such as Danton were guillotined in the spring of 1794. On 7 June, Robespierre, who favored deism over Hébert's atheism, and had previously condemned the Cult of Reason, recommended that the convention acknowledge the existence of his god. On the next day, the worship of the deistic Supreme Being was inaugurated as an official aspect of the revolution. Compared with Hébert's somewhat popular festivals, this austere new religion of Virtue was received with signs of hostility by the Parisian public.

Fall of Robespierre

The repression brought thousands of suspects before the Paris Revolutionary Tribunal, whose work was expedited by the Law of 22 Prairial (10 June 1794). As a result of Robespierre's insistence on associating Terror with Virtue, his efforts to make the republic a morally united patriotic community became equated with the endless bloodshed. Finally, after 26 June's decisive military victory over Austria at the Battle of Fleurus, Robespierre was overthrown on 9 Thermidor (27 July).

One of the last groups to be executed during the terror were the Carmelite Nuns of Compiègne. The nuns were sentenced to death for refusing to give up their monastic vows. They were sent to the guillotine on 17 July 1794. The manner in which they approached their death, going freely up to the scaffold while singing the hymn Veni Creator Spiritus, had a great impact on the public mood in Paris and helped to turn it against the terror.[28]

The fall of Robespierre was brought about by a combination of those who wanted more power for the Committee of Public Safety, and a more radical policy than he was willing to allow, with the moderates who opposed the revolutionary government altogether. They had, between them, made the Law of 22 Prairial one of the charges against him, and after his fall, advocating terror would mean adopting the policy of a convicted enemy of the republic, endangering the advocate's own head. Robespierre tried to commit suicide before his execution by shooting himself, although the bullet only shattered his jaw. He was guillotined the next day.[29]

The reign of the standing Committee of Public Safety was ended. New members were appointed the day after Robespierre's execution, and term limits were imposed (a quarter of the committee retired every three months); its powers were reduced piece by piece.

This was not an entirely or immediately conservative period; no government of the Republic envisaged a Restoration, and Marat was reburied in the Panthéon in September.[30]

Gallery

-

Mass shootings at Nantes, 1793

-

"The Last Cart" before the 9th Thermidor, 1794

-

Portrait of André Antoine Bernard, one of the Jacobins responsible for the Reign of Terror

-

Revolutionary Tribunal

See also

References

- ↑ Terror, Reign of; Encyclopædia Britannica

- ↑ Linton, Marisa. "The Terror in the French Revolution" (PDF). Kingston University. Retrieved 2 December 2011.

- 1 2 3 Greer, Donald. Incidence of the Terror During the French Revolution: A Statistical Interpretation. 1935. Peter Smith Pub Inc. ISBN 978-0-8446-1211-9

- ↑ Edelstein, Dan. The Terror of Natural Right. 2009. New York: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-18438-8.

- ↑ "Liberty, Equality, Fraternity: Exploring the French Revolution".

- ↑ Such as the Law of Frimaire, passed in December 1973 to consolidate power onto the committee.

- ↑ Connelly, Owen (2006). The Wars of the French Revolution and Napoleon, 1792–1815. New York: Routledge Publishing. p. 39.

- ↑ Mathiez, Albert. A Realistic Necessity, in The French Revolution: Conflicting Interpretations. Selected and Edited by Frank Kafker, James M. Lauz, and Darline Gay Levy. Malabar, Florida: Krieger Publishing Company, 2002. p. 189.

- ↑ Mathiez, Albert. A Realistic Necessity, p. 192.

- ↑ Palmer, R.R. Twelve Who Ruled: The Year of the Terror in the French Revolution. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1989.

- ↑ Cobb, Richard. A Mentality Shaped by Circumstance, in The French Revolution: Conflicting Interpretations. Selected and Edited by Frank Kafker, James M. Lauz, and Darline Gay Levy. Malabar, Florida: Krieger Publishing Company, 2002. p. 200.

- ↑ Cobb, Richard. A Mentality Shaped by Circumstance, p. 204.

- ↑ Furet, Francois. A Deep-rooted Ideology as Well as Circumstance, in The French Revolution: Conflicting Interpretations. Selected and Edited by Frank Kafker, James M. Lauz, and Darline Gay Levy. Malabar, Florida: Krieger Publishing Company, 2002. p. 222.

- ↑ Furet, Francois. A Deep-rooted Ideology as Well as Circumstance, p. 224.

- ↑ Palmer, R.R. Twelve Who Ruled: The Year of the Terror in the French Revolution, p. 172.

- ↑ Jones, Peter. The French Revolution 1787–1804. Pearson Education, 2003, p. 57.

- 1 2 3 Linton, Marisa (August 2006). "Robespierre and the terror: Marisa Linton reviews the life and career of one of the most vilified men in history, (Maximilien Robespierre)(Biography)". History Today 8 (56): 23.

- ↑ Murders Without Assassins, by Jacques Heynen, 2008, ISBN 1409231143, p. 36

- ↑ Pageant of Europe, Raymond P. Stearns (ed), 1947

- ↑ Modern History SourceBook, by Paul Halsall, 1997, Web Link

- ↑ Stewart, John (1951). Documentary Survey of the French Revolution. The Macmillan Company. pp. 475–476.

- ↑ Gough, Hugh (2010). The Terror in the French Revolution (second ed.). Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 39–40.

- ↑ P.M. Jones - Reform and Revolution in France: The Politics of Transition, 1774-1791 . Cambridge University Press, 1995, p. 127

- ↑ "French Revolution". History.com. The History Channel. Retrieved 24 October 2007.

- ↑ Modern History SourceBook, Paul Halsall August 1997; Robespierre: On the Moral and Political Principles of Domestic Policy.

- ↑ 24 April 1793 – Declaration des droits de l'homme.

- 1 2 Latreille, A. (2003). "French Revolution". New Catholic Encyclopedia 5 (2nd ed.). Thomson-Gale. pp. 972–973. ISBN 0-7876-4004-2.

- ↑ Matthew E. Bunson, "They Sang All the Way to the Guillotine," Catholic Answers magazine (April 2007), Vol 8, no. 4

- ↑ Merriman, John (2004). "Thermidor" (2nd ed.). A history of modern Europe: from the Renaissance to the present, p 507. W.W. Norton & Company Ltd. ISBN 0-393-92495-5

- ↑ Marat. NNDB. Retrieved 2012-08-15.

Further reading

Secondary sources

- Andress, David (2006). The Terror: The Merciless War for Freedom in Revolutionary France. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ISBN 0-374-27341-3.

- Baker, Keith M. François Furet, and Colin Lucas, eds. (1987) The French Revolution and the Creation of Modern Political Culture, vol. 4, The Terror (London: Pergamon Press, 1987)

- Beik, William (August 2005). "The Absolutism of Louis XIV as Social Collaboration: Review Article". Past and Present 188: 195–224. doi:10.1093/pastj/gti019.

- Censer, Jack, and Lynn Hunt (2001). Liberty, Equality, Fraternity: Exploring the French Revolution. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press.

- Hunt, Lynn (1984). Politics, Culture, and Class in the French Revolution. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Gough, Hugh. The terror in the French revolution (London: Macmillan, 1998)

- Hibbert, Christopher (1981). The Days of the French Revolution. New York: Quill-William Morrow. ISBN 978-0-688-16978-7.

- Kerr, Wilfred Brenton (1985). Reign of Terror, 1793–1794. London: Porcupine Press. ISBN 0-87991-631-1.

- Linton, Marisa (August 2006). "Robespierre and the terror: Marisa Linton reviews the life and career of one of the most vilified men in history, (Maximilien Robespierre)(Biography)". History Today 8 (56): 23.

- Linton, Marisa, Choosing Terror: Virtue, Friendship and Authenticity in the French Revolution (Oxford University Press, 2013).

- Loomis, Stanley (1964). Paris in the Terror. New York: Dorset Press. ISBN 0-88029-401-9.

- Moore, Lucy (2006). Liberty: The Lives and Times of Six Women in Revolutionary France. London: HarperCollins. ISBN 0-00-720601-1.

- Steel, Mark (2003). Vive La Revolution. London: Scribner. ISBN 0-7432-0806-4.

- Reviewed by Adam Thorpe in The Guardian, 23 December 2006.

- Palmer, R. R. (2005). Twelve Who Ruled: The Year of the Terror in the French Revolution. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-12187-7.

- Schama, Simon (1989). Citizens: A Chronicle of the French Revolution. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. pp. 678–847. ISBN 0-394-55948-7.

- Scott, Otto (1974). Robespierre, The Fool as Revolutionary – Inside the French Revolution. Windsor, New York: The Reformer Library. ISBN 978-1-887690-05-8.

- Shulim, Joseph I. "Robespierre and the French Revolution," American Historical Review (1977) 82#1 pp. 20–38 in JSTOR

- Soboul, Albert. "Robespierre and the Popular Movement of 1793–4", Past and Present, No. 5. (May 1954), pp. 54–70. in JSTOR

- Sutherland, D.M.G. (2003) The French Revolution and Empire: The Quest for a Civic Order pp 174–253

- Weber, Caroline. (2003) Terror and Its Discontents: Suspect Words in Revolutionary France online

Historiography

- Kafker, Frank, James M. Lauz, and Darline Gay Levy (2002). The French Revolution: Conflicting Interpretations. Malabar, FL: Krieger Publishing Company.

- Rudé, George (1976). Robespierre: Portrait of a Revolutionary Democrat. New York: Viking Press. ISBN 0-670-60128-4. A Marxist political portrait of Robespierre, examining his changing image among historians and the different aspects of Robespierre as an 'ideologue', as a political democrat, as a social democrat, as a practitioner of revolution, as a politician and as a popular leader/leader of revolution, it also touches on his legacy for the future revolutionary leaders Vladimir Lenin and Mao Zedong.

Primary sources

- Cléry, Jean-Baptiste; Henry Essex Edgeworth (1961) [1798]. Sidney Scott, ed. Journal of the Terror. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. OCLC 3153946.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to French Revolution. |

- "The Terror" from In Our Time (BBC Radio 4)

|