d-ary heap

The d-ary heap or d-heap is a priority queue data structure, a generalization of the binary heap in which the nodes have d children instead of 2.[1][2][3] Thus, a binary heap is a 2-heap, and a ternary heap is a 3-heap. According to Tarjan[2] and Jensen et al.,[4] d-ary heaps were invented by Donald B. Johnson in 1975.[1]

This data structure allows decrease priority operations to be performed more quickly than binary heaps, at the expense of slower delete minimum operations. This tradeoff leads to better running times for algorithms such as Dijkstra's algorithm in which decrease priority operations are more common than delete min operations.[1][5] Additionally, d-ary heaps have better memory cache behavior than a binary heap, allowing them to run more quickly in practice despite having a theoretically larger worst-case running time.[6][7] Like binary heaps, d-ary heaps are an in-place data structure that uses no additional storage beyond that needed to store the array of items in the heap.[2][8]

Data structure

The d-ary heap consists of an array of n items, each of which has a priority associated with it. These items may be viewed as the nodes in a complete d-ary tree, listed in breadth first traversal order: the item at position 0 of the array forms the root of the tree, the items at positions 1–d are its children, the next d2 items are its grandchildren, etc. Thus, the parent of the item at position i (for any i > 0) is the item at position floor((i − 1)/d) and its children are the items at positions di + 1 through di + d. According to the heap property, in a min-heap, each item has a priority that is at least as large as its parent; in a max-heap, each item has a priority that is no larger than its parent.[2][3]

The minimum priority item in a min-heap (or the maximum priority item in a max-heap) may always be found at position 0 of the array. To remove this item from the priority queue, the last item x in the array is moved into its place, and the length of the array is decreased by one. Then, while item x and its children do not satisfy the heap property, item x is swapped with one of its children (the one with the smallest priority in a min-heap, or the one with the largest priority in a max-heap), moving it downward in the tree and later in the array, until eventually the heap property is satisfied. The same downward swapping procedure may be used to increase the priority of an item in a min-heap, or to decrease the priority of an item in a max-heap.[2][3]

To insert a new item into the heap, the item is appended to the end of the array, and then while the heap property is violated it is swapped with its parent, moving it upward in the tree and earlier in the array, until eventually the heap property is satisfied. The same upward-swapping procedure may be used to decrease the priority of an item in a min-heap, or to increase the priority of an item in a max-heap.[2][3]

To create a new heap from an array of n items, one may loop over the items in reverse order, starting from the item at position n − 1 and ending at the item at position 0, applying the downward-swapping procedure for each item.[2][3]

Analysis

In a d-ary heap with n items in it, both the upward-swapping procedure and the downward-swapping procedure may perform as many as logd n = log n / log d swaps. In the upward-swapping procedure, each swap involves a single comparison of an item with its parent, and takes constant time. Therefore, the time to insert a new item into the heap, to decrease the priority of an item in a min-heap, or to increase the priority of an item in a max-heap, is O(log n / log d). In the downward-swapping procedure, each swap involves d comparisons and takes O(d) time: it takes d − 1 comparisons to determine the minimum or maximum of the children and then one more comparison against the parent to determine whether a swap is needed. Therefore, the time to delete the root item, to increase the priority of an item in a min-heap, or to decrease the priority of an item in a max-heap, is O(d log n / log d).[2][3]

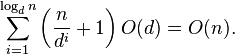

When creating a d-ary heap from a set of n items, most of the items are in positions that will eventually hold leaves of the d-ary tree, and no downward swapping is performed for those items. At most n/d + 1 items are non-leaves, and may be swapped downwards at least once, at a cost of O(d) time to find the child to swap them with. At most n/d2 + 1 nodes may be swapped downward two times, incurring an additional O(d) cost for the second swap beyond the cost already counted in the first term, etc. Therefore, the total amount of time to create a heap in this way is

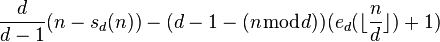

The exact value of the above (the worst-case number of comparisons during the construction of d-ary heap) is known to be equal to:

,[9]

,[9]

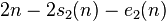

where sd(n) is the sum of all digits of the standard base-d representation of n and ed(n) is the exponent of d in the factorization of n. This reduces to

,[9]

,[9]

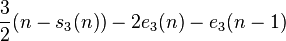

for d = 2, and to

,[9]

,[9]

for d = 3.

The space usage of the d-ary heap, with insert and delete-min operations, is linear, as it uses no extra storage other than an array containing a list of the items in the heap.[2][8] If changes to the priorities of existing items need to be supported, then one must also maintain pointers from the items to their positions in the heap, which again uses only linear storage.[2]

Applications

Dijkstra's algorithm for shortest paths in graphs and Prim's algorithm for minimum spanning trees both use a min-heap in which there are n delete-min operations and as many as m decrease-priority operations, where n is the number of vertices in the graph and m is the number of edges. By using a d-ary heap with d = m/n, the total times for these two types of operations may be balanced against each other, leading to a total time of O(m logm/n n) for the algorithm, an improvement over the O(m log n) running time of binary heap versions of these algorithms whenever the number of edges is significantly larger than the number of vertices.[1][5] An alternative priority queue data structure, the Fibonacci heap, gives an even better theoretical running time of O(m + n log n), but in practice d-ary heaps are generally at least as fast, and often faster, than Fibonacci heaps for this application.[10]

4-heaps may perform better than binary heaps in practice, even for delete-min operations.[2][3] Additionally, a d-ary heap typically runs much faster than a binary heap for heap sizes that exceed the size of the computer's cache memory: A binary heap typically requires more cache misses and virtual memory page faults than a d-ary heap, each one taking far more time than the extra work incurred by the additional comparisons a d-ary heap makes compared to a binary heap.[6][7]

References

- 1 2 3 4 Johnson, D. B. (1975), "Priority queues with update and finding minimum spanning trees", Information Processing Letters 4 (3): 53–57, doi:10.1016/0020-0190(75)90001-0.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Tarjan, R. E. (1983), "3.2. d-heaps", Data Structures and Network Algorithms, CBMS-NSF Regional Conference Series in Applied Mathematics 44, Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics, pp. 34–38.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Weiss, M. A. (2007), "d-heaps", Data Structures and Algorithm Analysis (2nd ed.), Addison-Wesley, p. 216, ISBN 0-321-37013-9.

- ↑ Jensen, C.; Katajainen, J.; Vitale, F. (2004), An extended truth about heaps (PDF).

- 1 2 Tarjan (1983), pp. 77 and 91.

- 1 2 Naor, D.; Martel, C. U.; Matloff, N. S. (1991), "Performance of priority queue structures in a virtual memory environment", Computer Journal 34 (5): 428–437, doi:10.1093/comjnl/34.5.428.

- 1 2 Kamp, Poul-Henning (2010), "You're doing it wrong", ACM Queue 8 (6).

- 1 2 Mortensen, C. W.; Pettie, S. (2005), "The complexity of implicit and space efficient priority queues", Algorithms and Data Structures: 9th International Workshop, WADS 2005, Waterloo, Canada, August 15–17, 2005, Proceedings, Lecture Notes in Computer Science 3608, Springer-Verlag, pp. 49–60, doi:10.1007/11534273_6, ISBN 978-3-540-28101-6.

- 1 2 3 Suchenek, Marek A. (2012), "Elementary Yet Precise Worst-Case Analysis of Floyd's Heap-Construction Program", Fundamenta Informaticae (IOS Press) 120 (1): 75–92, doi:10.3233/FI-2012-751.

- ↑ Cherkassky, B. V.; Goldberg, A. V.; Radzik, T. (1996), "Shortest paths algorithms: Theory and experimental evaluation", Mathematical Programming 73 (2): 129–174, doi:10.1007/BF02592101.