Tensor field

In mathematics, physics, and engineering, a tensor field assigns a tensor to each point of a mathematical space (typically a Euclidean space or manifold). Tensor fields are used in differential geometry, algebraic geometry, general relativity, in the analysis of stress and strain in materials, and in numerous applications in the physical sciences and engineering. As a tensor is a generalization of a scalar (a pure number representing a value, like length) and a vector (a geometrical arrow in space), a tensor field is a generalization of a scalar field or vector field that assigns, respectively, a scalar or vector to each point of space.

Many mathematical structures informally called "tensors" are actually tensor fields. An example is the Riemann curvature tensor.

Geometric introduction

Intuitively, a vector field is best visualized as an 'arrow' attached to each point of a region, with variable length and direction. One example of a vector field on a curved space is a weather map showing horizontal wind velocity at each point of the Earth's surface.

The general idea of tensor field combines the requirement of richer geometry – for example, an ellipsoid varying from point to point, in the case of a metric tensor – with the idea that we don't want our notion to depend on the particular method of mapping the surface. It should exist independently of latitude and longitude, or whatever particular 'cartographic projection' we are using to introduce numerical coordinates.

The vector bundle explanation

The contemporary mathematical expression of the idea of tensor field breaks it down into a two-step concept.

There is the idea of vector bundle, which is a natural idea of 'vector space depending on parameters' – the parameters being in a manifold M. For example a vector space of one dimension depending on an angle could look like a Möbius strip as well as a cylinder. Given a vector bundle V over M, the corresponding field concept is called a section of the bundle: for m varying over M, a choice of vector

- vm in Vm,

the vector space 'at' m.

Since the tensor product concept is independent of any choice of basis, taking the tensor product of two vector bundles on M is routine. Starting with the tangent bundle (the bundle of tangent spaces) the whole apparatus explained at component-free treatment of tensors carries over in a routine way – again independently of coordinates, as mentioned in the introduction.

We therefore can give a definition of tensor field, namely as a section of some tensor bundle. (There are vector bundles which are not tensor bundles: the Möbius band for instance.) This is then guaranteed geometric content, since everything has been done in an intrinsic way. More precisely, a tensor field assigns to any given point of the manifold a tensor in the space

where V is the tangent space at that point and V* is the cotangent space. See also tangent bundle and cotangent bundle.

Given two tensor bundles E → M and F → M, a map A: Γ(E) → Γ(F) from the space of sections of E to sections of F can be considered itself as a tensor section of  if and only if it satisfies A(fs,...) = fA(s,...) in each argument, where f is a smooth function on M. Thus a tensor is not only a linear map on the vector space of sections, but a C∞(M)-linear map on the module of sections. This property is used to check, for example, that even though the Lie derivative and covariant derivative are not tensors, the torsion and curvature tensors built from them are.

if and only if it satisfies A(fs,...) = fA(s,...) in each argument, where f is a smooth function on M. Thus a tensor is not only a linear map on the vector space of sections, but a C∞(M)-linear map on the module of sections. This property is used to check, for example, that even though the Lie derivative and covariant derivative are not tensors, the torsion and curvature tensors built from them are.

Notation

The notation for tensor fields can sometimes be confusingly similar to the notation for tensor spaces. Thus, the tangent bundle TM = T(M) might sometimes be written as

to emphasize that the tangent bundle is the range space of the (1,0) tensor fields (i.e., vector fields) on the manifold M. Do not confuse this with the very similar looking notation

;

;

in the latter case, we just have one tensor space, whereas in the former, we have a tensor space defined for each point in the manifold M.

Curly (script) letters are sometimes used to denote the set of infinitely-differentiable tensor fields on M. Thus,

are the sections of the (m,n) tensor bundle on M which are infinitely-differentiable. A tensor field is an element of this set.

The C∞(M) module explanation

There is another more abstract (but often useful) way of characterizing tensor fields on a manifold M which turns out to actually make tensor fields into honest tensors (i.e. single multilinear mappings), though of a different type (although this is not usually why one often says "tensor" when one really means "tensor field"). First, we may consider the set of all smooth (C∞) vector fields on M,  (see the section on notation above) as a single space &3; a module over the ring of smooth functions, C∞(M), by pointwise scalar multiplication. The notions of multilinearity and tensor products extend easily to the case of modules over any commutative ring.

(see the section on notation above) as a single space &3; a module over the ring of smooth functions, C∞(M), by pointwise scalar multiplication. The notions of multilinearity and tensor products extend easily to the case of modules over any commutative ring.

As a motivating example, consider the space  of smooth covector fields (1-forms), also a module over the smooth functions. These act on smooth vector fields to yield smooth functions by pointwise evaluation, namely, given a covector field ω and a vector field X, we define

of smooth covector fields (1-forms), also a module over the smooth functions. These act on smooth vector fields to yield smooth functions by pointwise evaluation, namely, given a covector field ω and a vector field X, we define

- (ω(X))(p) = ω(p)(X(p)).

Because of the pointwise nature of everything involved, the action of ω on X is a C∞(M)-linear map, that is,

- (ω(fX))(p) = f(p) ω(p)(X(p)) = (fω)(p)(X(p))

for any p in M and smooth function f. Thus we can regard covector fields not just as sections of the cotangent bundle, but also linear mappings of vector fields into functions. By the double-dual construction, vector fields can similarly be expressed as mappings of covector fields into functions (namely, we could start "natively" with covector fields and work up from there).

In a complete parallel to the construction of ordinary single tensors (not fields!) on M as multilinear maps on vectors and covectors, we can regard general (k,l) tensor fields on M as C∞(M)-multilinear maps defined on l copies of  and k copies of

and k copies of  into C∞(M).

into C∞(M).

Now, given any arbitrary mapping T from a product of k copies of  and l copies of

and l copies of  into C∞(M), it turns out that it arises from a tensor field on M if and only if it is a multilinear over C∞(M). Thus this kind of multilinearity implicitly expresses the fact that we're really dealing with a pointwise-defined object, i.e. a tensor field, as opposed to a function which, even when evaluated at a single point, depends on all the values of vector fields and 1-forms simultaneously.

into C∞(M), it turns out that it arises from a tensor field on M if and only if it is a multilinear over C∞(M). Thus this kind of multilinearity implicitly expresses the fact that we're really dealing with a pointwise-defined object, i.e. a tensor field, as opposed to a function which, even when evaluated at a single point, depends on all the values of vector fields and 1-forms simultaneously.

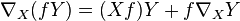

A frequent example application of this general rule is showing that the Levi-Civita connection, which is a mapping of smooth vector fields  taking a pair of vector fields to a vector field, does not define a tensor field on M. This is because it is only R-linear in Y (in place of full C∞(M)-linearity, it satisfies the Leibniz rule,

taking a pair of vector fields to a vector field, does not define a tensor field on M. This is because it is only R-linear in Y (in place of full C∞(M)-linearity, it satisfies the Leibniz rule,  )). Nevertheless it must be stressed that even though it is not a tensor field, it still qualifies as a geometric object with a component-free interpretation.

)). Nevertheless it must be stressed that even though it is not a tensor field, it still qualifies as a geometric object with a component-free interpretation.

Applications

The curvature tensor is discussed in differential geometry and the stress–energy tensor is important in physics and engineering. Both of these are related by Einstein's theory of general relativity. In engineering, the underlying manifold will often be Euclidean 3-space.

It is worth noting that differential forms, used in defining integration on manifolds, are a type of tensor field.

Tensor calculus

In theoretical physics and other fields, differential equations posed in terms of tensor fields provide a very general way to express relationships that are both geometric in nature (guaranteed by the tensor nature) and conventionally linked to differential calculus. Even to formulate such equations requires a fresh notion, the covariant derivative. This handles the formulation of variation of a tensor field along a vector field. The original absolute differential calculus notion, which was later called tensor calculus, led to the isolation of the geometric concept of connection.

Twisting by a line bundle

An extension of the tensor field idea incorporates an extra line bundle L on M. If W is the tensor product bundle of V with L, then W is a bundle of vector spaces of just the same dimension as V. This allows one to define the concept of tensor density, a 'twisted' type of tensor field. A tensor density is the special case where L is the bundle of densities on a manifold, namely the determinant bundle of the cotangent bundle. (To be strictly accurate, one should also apply the absolute value to the transition functions – this makes little difference for an orientable manifold.) For a more traditional explanation see the tensor density article.

One feature of the bundle of densities (again assuming orientability) L is that Ls is well-defined for real number values of s; this can be read from the transition functions, which take strictly positive real values. This means for example that we can take a half-density, the case where s = ½. In general we can take sections of W, the tensor product of V with Ls, and consider tensor density fields with weight s.

Half-densities are applied in areas such as defining integral operators on manifolds, and geometric quantization.

The flat case

When M is a Euclidean space and all the fields are taken to be invariant by translations by the vectors of M, we get back to a situation where a tensor field is synonymous with a tensor 'sitting at the origin'. This does no great harm, and is often used in applications. As applied to tensor densities, it does make a difference. The bundle of densities cannot seriously be defined 'at a point'; and therefore a limitation of the contemporary mathematical treatment of tensors is that tensor densities are defined in a roundabout fashion.

Cocycles and chain rules

As an advanced explanation of the tensor concept, one can interpret the chain rule in the multivariable case, as applied to coordinate changes, also as the requirement for self-consistent concepts of tensor giving rise to tensor fields.

Abstractly, we can identify the chain rule as a 1-cocycle. It gives the consistency required to define the tangent bundle in an intrinsic way. The other vector bundles of tensors have comparable cocycles, which come from applying functorial properties of tensor constructions to the chain rule itself; this is why they also are intrinsic (read, 'natural') concepts.

What is usually spoken of as the 'classical' approach to tensors tries to read this backwards – and is therefore a heuristic, post hoc approach rather than truly a foundational one. Implicit in defining tensors by how they transform under a coordinate change is the kind of self-consistency the cocycle expresses. The construction of tensor densities is a 'twisting' at the cocycle level. Geometers have not been in any doubt about the geometric nature of tensor quantities; this kind of descent argument justifies abstractly the whole theory.

See also

References

- The Geometry of Physics (3rd edition), T. Frankel, Cambridge University Press, 2012, ISBN 978-1107-602601

- McGraw Hill Encyclopaedia of Physics (2nd Edition), C.B. Parker, 1994, ISBN 0-07-051400-3

- Encyclopaedia of Physics (2nd Edition), R.G. Lerner, G.L. Trigg, VHC publishers, 1991, ISBN (Verlagsgesellschaft) 3-527-26954-1, ISBN (VHC Inc.) 0-89573-752-3

- Gravitation, J.A. Wheeler, C. Misner, K.S. Thorne, W.H. Freeman & Co, 1973, ISBN 0-7167-0344-0

- Relativity DeMystified, D. McMahon, Mc Graw Hill (USA), 2006, ISBN 0-07-145545-0

- Relativity, Gravitation, and Cosmology, R.J.A. Lambourne, Open University, Cambridge University Press, 2010, ISBN 9-780521-131384

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||