Taxonomy of Narcissus

| Narcissus Temporal range: 24–0 Ma Late Oligocene - Recent | |

|---|---|

| |

| Narcissus poeticus | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Monocots |

| Order: | Asparagales |

| Family: | Amaryllidaceae |

| Subfamily: | Amaryllidoideae |

| Tribe: | Narcisseae |

| Genus: | Narcissus L.[1] |

| Type species | |

| Narcissus poeticus L. | |

| Subgenera | |

The taxonomy of Narcissus is complex, and still not fully resolved. Known to the ancients, the genus name appears in Graeco-Roman literature, although their interest was as much medicinal as botanical. It is unclear which species the ancients were familiar with. Although frequently mentioned in Mediaeval and Renaisance texts it was not formally described till the work of Linnaeus in 1753. By 1789 it had been grouped into a family (Narcissi) but shortly thereafter this was renamed Amaryllideae, from which comes the modern placement within Amaryllidaceae, although for a while it was considered part of Liliaceae.

Many of the species now considered to be Narcissus were in separate genera during the nineteenth century, and the situation was further confused by the inclusion of many cultivated varieties. By 1875 the current circumscription was relatively settled. By 2004 phylogenetic studies had allowed the place of Narcissus within its fairly large family to be established, nested within a series of subfamilies (Amaryllidoideae) and tribes (Narcisseae). It shares its position in the latter tribe with Sternbergia.

The infrageneric classification has been even more complex and many schemes of subgenera, sections, subsections and series have been proposed, although all had certain similarities. Most authorities now consider there to be 10 – 11 sections based on phylogenetic evidence. The problems have largely arisen from the diversity of the wild species, frequent natural hybridisation and extensive cultivation with escape and subsequent naturalisation. The number of species has varied anywhere from 16 to nearly 160, but is probably around 50 – 60.

The genus appeared some time in the Late Oligocene to Early Miocene eras, around 24 million years ago, in the Iberian peninsula. While the exact origin of the word Narcissus is unknown it is frequently linked to its fragrance which was thought to be narcotic, and to the legend of the youth of that name who fell in love with his reflection. In the English language the common name Daffodil appears to be derived from the Asphodel with which it was commonly compared.

History

Genus valde intricatum et numerosissimis dubiis oppressum

A genus that is very complex and burdened with numerous uncertainties— Schultes & Schultes fil., Syst. Veg. 1829[2]

Early

Narcissus was first described by Theophrastus (Θεόφραστος, c 371 - c 287 BC) in his Historia Plantarum (Greek: Περὶ φυτῶν ἱστορία) as νάρκισσος, referring to N. poeticus, but comparing it to Asphodelus (ασφοδελωδες).[3] Theophrastus' description was frequently referred to at length by later authors writing in Latin such as Pliny the Elder (Gaius Plinius Secundus, 23 AD – 79 AD) from whom came the Latin form narcissus (see also Culture). Pliny's account comes to us in his Natural History (Latin: Naturalis Historia). Like his contemporaries, his interests were as much therapeutic[4][5] as botanical.[6][7] Another much cited Greek authority was Dioscorides (Διοσκουρίδης, 40 AD – 90 AD) in his De Materia Medica (Greek: Περὶ ὕλης ἰατρικῆς).[8] Both authors were to remain influential till at least the Renaisance, given that their descriptions went beyond the merely botanical, to the therapeutic (see also Antiquity).

An early European reference is found in the work of Albert Magnus (c. 1200 – 1280), who noted in his De vegetabilibus et plantis the similarity to the leek. William Turner in his A New Herball (1551) cites all three extensively in his description of the plant and its properties.[9][10] It was to remain to Linnaeus in 1753 to formally describe and name Narcissus as a genus in his Species Plantarum, at which time there were six known species (N. poeticus, N. pseudonarcissus, N. bulbocodium, N. serotinus, N. jonqulla and N. tazetta).[1] At that time, Linnaeus loosely grouped it together with 50 other genera into his Hexandria monogynia.[11]

Modern

It was de Jussieu in 1789 who first formally created a 'family' (Narcissi), as the seventh 'Ordo' (Order) of the third class (Stamina epigyna) of Monocots in which Narcissus and 15 other genera were placed.[12] The use of the term Ordo at that time was closer to what we now understand as Family, rather than Order.[13][14] The family has undergone much reorganisation since then, but in 1805 it was renamed after a different genus in the family, Amaryllis, as 'Amaryllideae' by Jaume St.-Hilaire and has retained that association since. Jaume St.-Hilaire divided the family into two unnamed sections and recognised five species of Narcissus, omitting N. serotinus.[15]

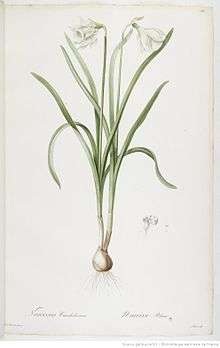

De Candolle brought together Linnaeus' genera and Jussieau's families into a systematic taxonomy for the first time, but included Narcissus (together with Amaryllis) in the Liliaceae in his Flore française (1805-1815) rather than Amaryllidaceae, a family he had not yet recognised.[16][17] Shortly thereafter he separated the 'Amaryllidées' from 'Liliacées' (1813),[18] though attributing the term to Brown's 'Amaryllideae' in the latter's Prodromus (1810)[19] rather than St.-Hilaire's 'Amaryllidées'. He also provided the text to the first four volumes of Redouté illustrations in the latter's Les liliacées between 1805 and 1808 (see illustration here of N. candidissimus).[20]

Historically both wide and narrow interpretations of the genus have been proposed. In the nineteenth century genus splitting was common,[21] favouring the narrow view. Haworth (1831) using a narrow view treated many species as separate genera,[22][23] as did Salisbury (1866).[24] These authors listed various species in related genera such as Queltia (hybrids), Ajax(=Pseudonarcissus) and Hermione(=Tazettae),[25] sixteen in all in Haworth's classification. In contrast, Herbert (1837) took a very wide view reducing Harworth's sixteen genera to six.[26] Herbert, treating the Amaryllidacea as an 'order' as was common then, considered the narcissi to be a suborder, the Narcisseae, the six genera being Corbularia, Ajax, Ganymedes, Queltia, Narcissus and Hermione and his relatively narrow circumscription of Narcissus having only three species. Later Spach (1846) took an even wider view bringing most of Harworth's genera into the genus Narcissus, but as separate subgenera.[27] By the time that Baker (1875) wrote his monograph all of the genera with one exception were included as Narcissus.[28] The exception was the monotypic group Tapeinanthus which various subsequent authors have chosen to either exclude (e.g. Cullen 1986[29]) or include (e.g. Webb 1978,[21] 1980[30]). Today it is nearly always included.[31]

The eventual position of Narcissus within the Amaryllidaceae family only became settled in the twenty-first century with the advent of phylogenetic analysis and the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group system.[11][32] The genus Narcissus belongs to the Narcisseae tribe, one of 13 within the Amaryllidoideae subfamily of the Amaryllidaceae.[33] It is one of two sister clades corresponding to genera in the Narcisseae,[34] being distinguished from Sternbergia by the presence of a paraperigonium, and is monophyletic.[35]

Subdivision

| Fernandes 1975[36][37] | Webb 1978[21] | Blanchard 1990[38] | Mathew 2002[31] | Zonneveld 2008[39] | RHS 2013[40] | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subgenus | Section | Subsection | Section | Subsection | Section | Subsection | Subgenus | Section | Subsection | Series | Subgenus | Section | Section |

| Hermione | Serotini | Serotini | Serotini | Hermione | Hermione | Serotini | Hermione | Serotini | Serotini | ||||

| Hermione | Angustifolii | Tazettae | Angustifoliae | Tazettae | Angustifoliae | Angustifoliae | Tazettae | Tazettae | |||||

| Hermione | Tazettae | Tazettae | Hermione | Hermione | |||||||||

| Aurelia | Aurelia | Aurelia | Albiflorae | ||||||||||

| Aurelia | Aurelia | ||||||||||||

| Narcissus | Apodanthi | Apodanthae | Narcissus | Jonquillae | Apodanthi | Narcissus | Apodanthi | Apodanthi | |||||

| Jonquilla | Jonquilla | Jonquillae | Jonquillae | Jonquillae | Jonquillae | Jonquilla | Jonquilla | ||||||

| Juncifolii | Apodanthi | Chloranthi | Juncifolii | ||||||||||

| Tapeinanthus | Tapeinanthus | Tapeinanthus | Tapeinanthus | Tapeinanthus | Tapeinanthus | ||||||||

| Ganymedes | Ganymedes | Ganymedes | Ganymedes | Ganymedes | Ganymedes | ||||||||

| Bulbocodium | Bulbocodium | Bulbocodium | Bulbocodium | Bulbocodium | |||||||||

| Pseudonarcissus | Pseudonarcissi | Pseudonarcissi | Pseudonarcissus | Pseudonarcissus | Pseudonarcissus | Pseudonarcissus | |||||||

| Reflexi | Nevadensis | ||||||||||||

| Narcissus | Narcissus | Narcissus | Narcissus | Narcissus | Narcissus | ||||||||

| Chloranthi (N. viridiflorus) | Corbularia syn. Bulbocodium | ||||||||||||

The infrageneric phylogeny of Narcissus still remains relatively unsettled.[33] The taxonomy has proved very complex and difficult to resolve,[30][31] particularly for the Pseudonarcissus group.[41] This is due to a number of factors, including the diversity of the wild species, the ease with which natural hybridisation occurs, and extensive cultivation and breeding accompanied by escape and naturalisation.[33][39]

De Candolle, in the first systematic taxonomy of Narcissus, arranged the species into named groups, and those names (Faux-Narcisse or Pseudonarcissus, Poétiques, Tazettes, Bulbocodiens, Jonquilles) have largely endured for the various subdivisions since and bear his name.[16][17] The evolution of classification was confused by including many unknown or garden varieties, until Baker (1875) made the important distinction of excluding all specimens except the wild species from his system. He then grouped all of the earlier related genera as sections under one genus, Narcissus, the exception being the monotypic Tapeinanthus.[28] Consequently, the number of accepted species has varied widely.[39]

A common modern classification system has been that of Fernandes (1951, 1968, 1975)[36][37][42] based on cytology, as modified by Blanchard (1990)[38][43] and Mathew (2002),[31] although in some countries such as Germany, the system of Meyer (1966) was preferred.[44] Fernandes described two subgenera based on basal chromosome number, Hermione, n = 5 (11) and Narcissus, n = 7 (13). He further subdivided these into ten sections (Apodanthi, Aurelia, Bulbocodii, Ganymedes, Jonquillae, Narcissus, Pseudonarcissi, Serotini, Tapeinanthus, Tazettae), as did Blanchard later.[43]

In contrast to Fernandes, Webb's treatment of the genus for the Flora Europaea (1978,[21] 1980[30]) prioritised morphology over genetics, and abandoned the subgenera ranks. He also restored De Candolle's original nomenclature, and made a number of changes to section Jonquilla, merging the existing subsections, reducing Apodanthi to a subsection of Jonquilla, and moving N. viridiflorus from Jonquilla to a new monotypic section of its own (Chloranthi). Finally, he divided Pseudonarcissus into two subsections. Blanchard (1990), whose Narcissus: a guide to wild daffodils has been very influential, adopted a simple approach, restoring Apodanthae, and based largely on ten sections alone.

The Royal Horticultural Society (RHS) currently lists ten sections, based on Fernandes (1968), three of which are monotypic (contain only one species), while two others only containing two species. Most species are placed in Pseudonarcissus[40] While infrageneric groupings within Narcissus have been relatively constant, their status (genera, subgenera, sections, subsections, series, species) has not.[31][33] Some authors treat some sections as being further subdivided into subsections, e.g. Tazettae (3 subsections).[45] These subdivisions correspond roughly to the popular names for narcissi types, e.g. Trumpet Daffodils, Tazettas, Pheasant's Eyes, Hoop Petticoats, Jonquils.[31]

While Webb had simply divided the genus into sections, Mathew found this unsatisfactory, implying every section had equal status. He adapted both Fernandes and Webb to devise a more hierarchical scheme he believed better reflected the interrelatinships within the genus. Mathew's scheme consists of three subgenera (Narcissus, Hermione and Corbularia). The first two subgenera were then divided into five and two sections respectively. He then further subdivided two of the sections (subgenus Narcissus section Jonqullae, and subgenus Hermione section Hermione) into three subsections each. Finally, he divided section Hermione subsection Hermione further into two series, Hermione and Albiflorae. While lacking a phylogenetic basis, the system is still in use in horticulture. For instance the Pacific Bulb Society uses his numbering system (see Table II) for classifying species.[46]

| Subgenus | Section | Subsection | Series | Type species |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Narcissus Pax | 1a. Narcissus L. | N. poeticus L. | ||

| 1b. Pseudonarcissus DC syn. Ajax Spach |  N. pseudonarcissus L. | |||

| 1c. Ganymedes Salisbury ex Schultes and Schultes fil. |  N. triandrus L. | |||

| 1d. Jonquillae De Candolle | 1d(i). Jonquillae DC |  N. jonquilla L. | ||

| 1d(ii). Apodanthi (A. Fernandes) D. A. Webb |  N. rupicola Dufour | |||

| 1d(iii). Chloranthi D. A. Webb |  N. viridiflorus Schousboe | |||

| 1e. Tapeinanthus (Herbert) Traub |  N. cavanillesii A. Barra and G. López | |||

| 2. Hermione (Salisbury) Spach | 2a. Hermione syn. Tazettae De Candolle | 2a(i). Hermione | 2a(i)A. Hermione |  N. tazetta L. |

| 2a(i)B. Albiflorae Rouy. |  N. papyraceous Ker-Gawler | |||

| 2a(ii). Angustifoliae (A. Fernandes) F.J Fernándes-Casas | Link to image N. elegans (Haw.) Spach | |||

| 2a(iii). Serotini Parlatore |  N. serotinus L. | |||

| 2b. Aurelia (J. Gay) Baker | N. broussonetii Lagasca | |||

| 3. Corbularia (Salisb.) Pax syn. Bulbocodium De Candolle |  N. bulbocodium L. | |||

Phylogenetics

| Narcissus Cladogram (Graham and Barrett 2004)[35] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The phylogenetic analysis of Graham and Barrett (2004) supported the infrageneric division of Narcissus into two clades corresponding to the subgenera Hermione and Narcissus, but does not support monophyly of all sections, with only Apodanthi demonstrating clear monophyly, corresponding to Clade III of Graham and Barrett (see Cladogram), although some other clades corresponded approximately to known sections.[35] These authors examined 36 taxa of the 65 listed then, and a later extended analysis by Rønsted et al. (2008) with five additional taxa confirmed this pattern.[47]

A very large (375 accessions) molecular analysis by Zonneveld (2008) utilising nuclear DNA content sought to reduce some of the paraphyly identified by Graham and Barrett. This led to a revision of the sectional structure, shifting some species between sections, eliminating one section and creating two new ones. In subgenus Hermione, Aurelia was merged with Tazettae. In subgenus Narcissus section Jonquillae subsection Juncifolii was elevated to sectional rank, thus resolving the paraphyly in this section observed by Graham and Barrett in Clade II due to this anomalous subsection, the remaining species being in subsection Jonquillae, which was monophyletic. The relatively large section Pseudonarcissi was divided by splitting off a new section, Nevadensis (species from southern Spain) leaving species from France, northern Spain and Portugal in the parent section.[39] At the same time Fernández-Casas (2008) proposed a new monotypic section Angustini to accommodate Narcissus deficiens, placing it within subgenus Hermione.[45][48]

While Graham and Barrett (2004)[35] had determined that subgenus Hermione was monophyletic, using a much larger accession Santos-Gally et al. (2011)[45] did not. However the former had excluded species of hybrid origins, while the latter included both N. dubius and N. tortifolius. If these two species are excluded (forming a clade with subgenus Narcissus) then Hermione can be considered monophyletic, although as a section of Hermione, Tazettae is not monophyletic. They also confirmed the monophyly of Apodanthi.

Some so-called nothosections have been proposed, predominantly by Fernández-Casas, to accommodate natural ('ancient') hybrids (nothospecies).[48]

Subgenera and sections

Showing revisions by Zonnefeld (2008)[39]

- subgenus Hermione (Haw.) Spach.

- subgenus Narcissus L.

- Apodanthi A. Fernandes (6 species)

- Bulbocodium de Candolle (11 species)

- Ganymedes (Haworth) Schultes f. (monotypic)

- Jonquillae de Candolle (8 species)

- Juncifolii (A. Fern.) Zonn. sect. nov. (2008)[39]

- Narcissus L. (2 species)

- Nevadensis Zonn. sect. nov. (2008)[39]

- Pseudonarcissus de Candolle (36 species) Trumpet daffodils

- Tapeinanthus (Herbert) Traub (monotypic)

Species

Estimates of the number of species in Narcissus have varied widely, from anywhere between 16 to nearly 160,[38][39] even in the modern era. Linnaeus originally included six species in 1753. By the time of the 14th edition of the Systema Naturae in 1784, there were fourteen.[49] The 1819 Encyclopaedia Londinensis lists sixteen (see illustration here of three species)[50] and by 1831 Adrian Haworth had described 150 species.[22]

Much of the variation lies in the definition of species, and whether closely related taxa are considered separate species or subspecies. Thus, a very wide view of each species, such as Webb's[30] results in few species, while a very narrow view such as that of Fernandes[36] results in a larger number.[31] Another factor is the status of hybrids, given natural hybridisation, with a distinction between 'ancient hybrids' and 'recent hybrids'. The term 'ancient hybrid' refers to hybrids found growing over a large area, and therefore now considered as separate species, while 'recent hybrid' refers to solitary plants found amongst their parents, with a more restricted range.[39]

In the twentieth century Fernandes (1951) accepted 22 species,[42] on which were based the 27 species listed by Webb in the 1980 Flora Europaea.[30] By 1968, Fernandes had accepted 63 species,[36] and by 1990 Blanchard listed 65 species,[38] and Erhardt 66 in 1993.[51] In 2006 the Royal Horticultural Society's (RHS) International Daffodil Register and Classified List [40][52][53] listed 87 species, while Zonneveld's genetic study (2008) resulted in only 36.[39] As of September 2014, the World Checklist of Selected Plant Families accepts 52 species, along with at least 60 hybrids,[54] while the RHS has 81 accepted names in its October 2014 list.[55]

Evolution

Within the Narcisseae, Narcissus (western Mediterranean) diverged from Sternbergia (Eurasia) some time in the Late Oligocene to Early Miocene eras, around 29.3–18.1 Ma, with a best estimate of 23.6 Ma. Later the genus divided into the two subgenera (Hermione and Narcissus) between 27.4–16.1 Ma (21.4 Ma). The divisions between the sections of Hermione then took place during the Miocene period 19.9–7.8 Ma.[45]

Narcissus appears to have arisen in the area of the Iberian peninsula, southern France and north-western Italy, and within this area most sections of the genus appeared, with only a few taxa being dispersed to North Africa at a time when the African and West European platforms were closer together. Subgenus Hermione in turn arose in the southwestern mediterranean and north west Africa. However, these are reconstructions, the Amaryllidaceae lacking a fossil record.[45]

Etymology

Narcissus

The derivation of the Latin narcissus (Greek: νάρκισσος) is unknown. It may be a loanword from another language, for instance it is said to be related to the Sanskrit word nark, meaning 'hell'.[56] It is frequently linked to the Greek myth of Narcissus described by Ovid in his Metamorphoses, who became so obsessed with his own reflection that as he knelt and gazed into a pool of water, he fell into the water and drowned. In some variations, he died of starvation and thirst. In both versions, the narcissus plant sprang from where he died. Although Ovid appeared to describe the plant we now know as Narcissus there is no evidence for this popular derivation, and the person's name may have come from the flower's name. The Poet's Narcissus (N. poeticus), which grows in Greece, has a fragrance that has been described as intoxicating. Again, this explanation lacks any real proof and is largely discredited.[57] Pliny wrote that the plant ‘narce narcissum dictum, non a fabuloso puero’[4] (named narcissus from narce, not from the legendary youth), i.e. that it was named for its narcotic properties (ναρκάω narkao, "I grow numb" in Greek), not from the legend.[33][58][59] Furthermore, there were accounts of narcissi growing, such as in the legend of Persephone, long before the story of Narcissus appeared (see Greek culture).[56][60][notes 1] It has also been suggested that daffodils bending over streams evoked the image of the youth admiring his own reflection in the water.[61]

Linnaeus used the Latin name for the plant in formally describing the genus, although Matthias de l'Obel had previously used the name in describing various species of Narcissi in his Icones stirpium of 1591, and other publications,[62] as had Clusius in Rariorum stirpium (1576).[63]

The plural form of the common name narcissus has caused some confusion. British English sources such as the Shorter Oxford English Dictionary[57] give two alternate forms, narcissi and narcissuses. In contrast, in American English the Merriam-Webster Dictionary provides for a third form, narcissus, used for both singular and plural.[64] The Oxford dictionaries only list this third form under American English, although the Cambridge Dictionary[65] allows of all three in the same order. However, Garner's Modern American Usage states that narcissi is the commonest form, narcissus being excessively sibilant.[66] For similar reasons, Fowler prefers narcissi in British English usage.[67] Neither support narcissus as a plural form. Common names such as narcissus do not capitalise the first letter in contrast to the person of that name and the Latin genus name.

The name Narcissus (feminine Narcissa) was not uncommon in Roman times,[68] such as Tiberius Claudius Narcissus, a Roman official in Claudius' time,[69] an early New Testament Christian in Rome[70] and later bishops and saints.[71]

Daffodil

The word daffodil was unknown in the English language before the sixteenth century.[72] The name is derived from an earlier affodell, a variant of asphodel. In classical Greek literature the narcissus is frequently, referred to as the asphodel,[58] such as the meadows of the Elysian fields in Homer (see Antiquity). Asphodel in turn appears to be a loanword coming from French via Mediaeval Latin affodilus from Classical Latin asphodilus and ultimately the Greek asphodelos (Greek: ἀσφόδελος).[58][73] The reason for the introduction of the initial d is not known, although a probable source is an etymological merging from the Dutch article de, as in de affodil, or English the, as th'affodil or t'affodil, hence daffodil, and in French de and affodil to form fleur d'aphrodille and daphrodille.[74]

From at least the 16th century, daffadown dilly and daffydowndilly have appeared as playful synonyms of the name. In common parlance and in historical documents, the term daffodil may refer specifically to populations or specimens of the wild daffodil, N. pseudonarcissus.[57] Ellacombe suggests this may be from Saffon Lilly,[75] citing Prior[76] in support, though admittedly conjectural.

Lady Wilkinson (1858), who provides an extensive discussion of the etymology of the various names for this plant, suggests a very different origin, namely the Old English word affodyle (that which cometh early), citing a 14th-century (but likely originally much earlier) manuscript in support of this theory, and which appears to describe a plant resembling the daffodil.[77] Ellacombe provides further support for this from a fifteenth century English translation of Palladius that also refers to it.[75][notes 2]

Jonquil

The name jonquil is said to be a corruption via French from the Latin juncifolius meaning rush-leaf (Juncaceae) and its use is generally restricted to those species and cultivars which have rush like leaves, e.g. N. juncifolius.[75]

Other

A profusion of names have attached themselves in the English language, either to the genus as a whole or to individual species or groups of species such as sections. These include narcissus, jonquil, Lent lily, Lenten lily, lide lily, yellow lily, wort or wyrt, Julians, glens, Lent cocks, corn flower, bell rose, asphodel, Solomon's lily, gracy day, haverdrils, giggary, cowslip, and crow foot.[72]

References

- 1 2 Linnaeus, Carl (1753). Species Plantarum vol. 1. p. 289. Retrieved 2 October 2014.

- ↑ Schultes. Narcissus (vol. VII(2)). p. 932. Retrieved 25 October 2014. In Linnaeus (1829)

- ↑ Theophrastus. Historia Plantarum (VI vi). p. 9. Retrieved 28 October 2014. Historia Plantarum page 42 in Theophrastus (1916)

- 1 2 Gaius Plinius, Secundus. "Naturalis Historia xxi:74.". Retrieved 3 October 2014. In Plinius Secundus (1906)

- ↑ Pliny, The Elder. 75. Sixteen remedies derived from the Narcissus. pp. 367–368. Retrieved 3 October 2014. In Plinius Secundus (1856)

- ↑ Gaius Plinius, Secundus. "Naturalis Historia xxi:14.". Retrieved 4 October 2014. In Plinius Secundus (1906)

- ↑ Pliny, The Elder. 12. The Narcissus: Three varieties of it. p. 316. Retrieved 3 October 2014. In Plinius Secundus (1856)

- ↑ Dioscurides. νάρκισσος. pp. 302–303, IV: 158. Retrieved 20 October 2014. In Dioscuridis Anazarbei (1906)

- ↑ Turner, William (1551). "Of Narcissus". A New Herball - The Seconde Parte. pp. 61–62. Retrieved 28 October 2014. In Turner (1551, p. 462)

- ↑ Barr & Burbidge 1884, p. 7.

- 1 2 Meerow, Alan W.; Fay, Michael F.; Guy, Charles L.; Li, Qin-Bao; Zaman, Faridah Q. & Chase, Mark W. (1999). "Systematics of Amaryllidaceae based on cladistic analysis of plastid sequence data". American Journal of Botany 86 (9): 1325–1345. doi:10.2307/2656780. PMID 10487820.

- ↑ Jussieu, Antoine Laurent de (1789). "Narcissi". Genera Plantarum, secundum ordines naturales disposita juxta methodum in Horto Regio Parisiensi exaratam. Paris. pp. 54–56. OCLC 5161409. Retrieved 2 October 2014.

- ↑ "Names of families and subfamilies, tribes and subtribes". p. 18.2. Retrieved 1 February 2014. In ICN (2011).

- ↑ Des familles et des tribus. pp. 192–195. Retrieved 5 February 2014. In A. P. de Candolle (1813).

- ↑ Jaume-Saint-Hilaire, Jean Henri (1805). "Narcissus". Exposition de familles naturales (vol. 1). Paris: Treutel et Würtz. p. 138. Retrieved 25 October 2014.

- 1 2 De Candolle. Narcissus. pp. 230–232. Retrieved 29 October 2014. In De Lamarck & De Candolle (1815a)

- 1 2 De Candolle. Narcissus. pp. 319–327. Retrieved 29 October 2014. In De Lamarck & De Candolle (1815b)

- ↑ A. P. de Candolle 1813, p. 219.

- ↑ Brown 1810, Prodromus p. 296.

- 1 2 Redouté & De Candolle 1805–1808, vol. IV p. 188.

- 1 2 3 4 Webb 1978.

- 1 2 Haworth, A.H. (1831). Narcissinearum Monographia (PDF) (2 ed.). London: Ridgway. Retrieved 20 October 2014.

- ↑ Haworth's arrangement of Narcissus. pp. 59–61. Retrieved 1 November 2014. In Burbidge (1875)

- ↑ Salisbury. Narcisseae. pp. 98ff. Retrieved 26 October 2014. In Salisbury & Gray (1866)

- ↑ "Segregate and other genera". Royal Horticultural Society. Retrieved 1 November 2014.

- ↑ Herbert. Suborder 5. Narcisseae. pp. 62–63. Retrieved 20 October 2014. In Herbert (1837)

- ↑ Spach. Genre NARCISSE - Narcissus Linn. pp. 430–455. Retrieved 21 October 2014. In Spach (1846)

- 1 2 Baker, JG. Review of the genus Narcissus. pp. 61–86. Retrieved 1 October 2014. In Burbidge (1875)

- ↑ Cullen, James (2011). "Narcissus". In Cullen, James; Knees, Sabina G.; Cubey, H. Suzanne Cubey. The European Garden Flora, Flowering Plants: A Manual for the Identification of Plants Cultivated in Europe, Both Out-of-Doors and Under Glass. (vol. 1. Alismataceae to Orchidaceae) (2 ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 205 ff. ISBN 0521761476. Retrieved 21 October 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Webb, D. A. Narcissus L. pp. 78–84. Retrieved 4 October 2014. In Tutin & et al. (1980)

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Mathew, B. Classification of the genus Narcissus. pp. 30–52. Retrieved 2 October 2014. In Hanks (2002)

- ↑ Stevens, P.F., Angiosperm Phylogeny Website: Amaryllidaceae - 3. Amaryllidoideae - 3H. Narcisseae

- 1 2 3 4 5 Bastida, Jaume; Lavilla, Rodolfo; Viladomat, Francesc (2006). "Chemical and biological aspects of "Narcissus" alkaloids". In Cordell, G. A. The Alkaloids: Chemistry and Biology Vol. 63 (PDF). Amsterdam: Elsevier Inc. pp. 87–179. doi:10.1016/S1099-4831(06)63003-4. Retrieved 8 October 2014.

- ↑ Gage, Ewan; Wilkin, Paul; Chase, Mark W.; Hawkins, Julie (June 2011). "Phylogenetic systematics of Sternbergia (Amaryllidaceae) based on plastid and ITS sequence data". Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society 166 (2): 149–162. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8339.2011.01138.x. Retrieved 25 October 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 Graham, S. W.; Barrett, S. C. H. (1 July 2004). "Phylogenetic reconstruction of the evolution of stylar polymorphisms in Narcissus (Amaryllidaceae)". American Journal of Botany 91 (7): 1007–1021. doi:10.3732/ajb.91.7.1007. PMID 21653457. Retrieved 25 October 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 Fernandes, A. (1968). "Keys to the identification of native and naturalized taxa of the genus Narcissus L.". Daffodil and Tulip Year Book (vol. 33). pp. 37–66. Retrieved 23 October 2014.

- 1 2 Fernandes, A. (1975). "L'évolution chez le genre Narcissus L." (PDF). Anales del Instituto Botanico Antonio Jose Cavanilles 32: 843–872. Retrieved 25 October 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 Blanchard, J. W. (1990). Narcissus: a guide to wild daffodils. Surrey, UK: Alpine Garden Society. ISBN 0900048530.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Zonneveld, B. J. M. (24 September 2008). "The systematic value of nuclear DNA content for all species of Narcissus L. (Amaryllidaceae)". Plant Systematics and Evolution 275 (1-2): 109–132. doi:10.1007/s00606-008-0015-1.

- 1 2 3 "Botanical Classification". Royal Horticultural Society. 23 September 2013. Retrieved 27 October 2014.

- ↑ Medrano, Mónica; López-Perea, Esmeralda; Herrera, Carlos M. (June 2014). "Population Genetics Methods Applied to a Species Delimitation Problem: Endemic Trumpet Daffodils (Narcissus Section Pseudonarcissi) from the Southern Iberian Peninsula". International Journal of Plant Sciences 175 (5): 501–517. doi:10.1086/675977.

- 1 2 Fernandes, A (1951). "Sur la phylogenie des especes du genre Narcissus L.". Boletim da Sociedade Broteriana II 25: 113–190. Retrieved 4 October 2014.

- 1 2 "Key to the sections (following Blanchard 1990)". André Levy. Retrieved 23 October 2014.

- ↑ Meyer, F. G. (January 1966). "Narcissus species and wild hybrids" (PDF). Amer. Hort. Mag. 45 (1): 47–76. Retrieved 19 October 2014. In American Horticultural Society (1966)

- 1 2 3 4 5 Santos-Gally, Rocío; Vargas, Pablo; Arroyo, Juan (April 2012). "Insights into Neogene Mediterranean biogeography based on phylogenetic relationships of mountain and lowland lineages of (Amaryllidaceae)". Journal of Biogeography 39 (4): 782–798. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2699.2011.02526.x. Retrieved 20 October 2014.

- ↑ PBS Overview 2014.

- ↑ Rønsted, Nina; Savolainen, Vincent; Mølgaard, Per; Jäger, Anna K. (May–June 2008). "Phylogenetic selection of Narcissus species for drug discovery". Biochemical Systematics and Ecology 36 (5-6): 417–422. doi:10.1016/j.bse.2007.12.010.

- 1 2 Fernández-Casas, Francisco Javier (2008). "Narcissorum notulae, X" (PDF). Fontqueria 55: 547–558. Retrieved 20 October 2014.

- ↑ Linné 1784, p.316.

- ↑ Wilkes 1819.

- ↑ Erhardt, Walter (1993). Narzissen : Osterglocken, Jonquillen, Tazetten. Stuttgart (Hohenheim): E. Ulmer. ISBN 3800164892. Retrieved 18 October 2014.

- ↑ "Daffodil cultivar registration". Royal Horticultural Society. Retrieved 27 October 2014.

- ↑ "Search The International Daffodil Register & Classified List". Royal Horticultural Society. Retrieved 27 October 2014.

- ↑ "Narcissus". World Checklist of Selected Plant Families. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Retrieved September 2014.

- ↑ "Botanical names in the genus Narcissus". Royal Horticultural Society. October 2014. Retrieved 2 November 2014.

- 1 2 NARISSUS. p. 163. In Prior (1870)

- 1 2 3 Shorter Oxford English dictionary, 6th ed. United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. 2007. p. 3804. ISBN 0199206872. Retrieved 26 October 2014.

- 1 2 3 Dweck, A. C. The folklore of Narcissus (PDF). pp. 19–29. In Hanks (2002)

- ↑ Nigel Groom (30 June 1997). The New Perfume Handbook. Springer. pp. 225–226. ISBN 978-0-7514-0403-6. Retrieved 28 July 2012.

- ↑ Pausanias. "9. Boeotia". pp. 31: 9. Retrieved 19 October 2014. In Pausanias (1918)

- ↑ "Tongues in trees". Gardeners Chronicle & New Horticulturist vol VI III series, No 156. London: Haymarket Publishing. December 21, 1889. p. 718. Retrieved 6 October 2014.

- ↑ de l'Obel, Matthias (1591). Icones stirpium. Antwerp. pp. 112–122. Retrieved 26 October 2014.

- ↑ Clusius 1576, De Narcisso, ii pp. 245-256.

- ↑ "narcissus". Merriam-Webster. Encyclopaedia Brittanica. Retrieved 16 November 2014.

- ↑ "narcissus". Cambridge Dictionaries online. Cambridge University Press. Retrieved 16 November 2014.

- ↑ Garner, Brian (2009). "narcissus". Garner's Modern American Usage (3rd ed.). New York: Oxford University Press, USA. p. 559. ISBN 0199888779. Retrieved 16 November 2014.

- ↑ Allen, Robert, ed. (2008). "narcissus". Pocket Fowler's Modern English usage (2nd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 455. ISBN 019923258X. Retrieved 16 November 2014.

- ↑ Hunter 1939.

- ↑ Badian 2014.

- ↑ Paul 1611.

- ↑ Bible Hub 2014.

- 1 2 Dalton, Jan (March 2013). "The English Lent Lily" (PDF). Daffodil Society. Retrieved 20 November 2014.

- ↑ Oxford Dictionary of English (3 ed.). 2010.

- ↑ Reece, Steve (2007). "Homer’s Asphodel Meadow". Greek, Roman, and Byzantine Studies 47 (4): 389–400. Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- 1 2 3 Ellacombe 1884, Daffofils p. 73.

- ↑ DAFFADOWNDILLY, DAFFODILLY, AFFODILLY, and DAFFODIL. p. 61. In Prior (1870)

- ↑ Wilkinson 1858, The Daffodil p. 85.

Notes

- ↑ Prior here refers to the poet Pamphilus, but it is likely he meant Pamphos

- ↑ Palladius, the fourth century Roman agricultural writer was best known in English for a 15th-century translation into English, titled Palladius on Husbondrie, where the "affadille" is stated to be a suitable plant for bees to visit.(Palladius 1420, De apium castris p. 37, l. 1015) Other editions render this as "Affodyle".(Ellacombe 1884, Daffofils p. 73)

Bibliography

Antiquity

- Dioscuridis Anazarbei, Pedanii (1906). Wellman, Max, ed. De materia medica libri quinque. Volume II. Berlin: Apud Weidmannos. Retrieved 20 October 2014.

- Plinius Secundus, Gaius (Pliny the Elder) (1906). Mayhoff, Karl Friedrich Theodor, ed. "Naturalis Historia". Perseus Digital Library. Retrieved 3 October 2014.

- Plinius Secundus, Gaius (Pliny the Elder) (1856). Bostock, John; Riley, H. T., eds. Natural History Book XXI (Volume Four). London: Henry G Bohn. Retrieved 3 October 2014.

- Theophrastus (1916). Hort, Arthur, ed. Theophrastus: Enquiry into Plants vol. ii. London and New York: William Heinemann and G.P. Putnam's Sons: Loeb Classical Library.

- Badian, E (2014). "Narcissus: Roman official". Encyclopaedia Brittanica. Retrieved 28 December 2014.

- Hunter, SF (1939). "Narcissus". International Standard Bible Encyclopedia Online. Retrieved 28 December 2014.

- Paul, Saint (1611). "Epistle to the Romans" (King James Version 16: 11). Retrieved 28 December 2014.

Salute Herodion my kinsman. Greet them that be of the household of Narcissus, which are in the Lord.

- "Narcissus". Bible Hub. Retrieved 28 December 2014.

Mediaeval and Renaissance

- Turner, William (1551). Chapman, George T. L.; Tweddle, Marilyn N.; McCombie, Frank, eds. William Turner, a New Herball Parts II and III (1995 reprint. Original at Rare Book Room Spread 188). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521445493. Retrieved 2 November 2014.

- Clusius, Carolus (1576). Atrebat Rariorum alioquot stirpium per Hispanias observatarum historia: libris duobus expressas. Antwerp: Plantinus. Retrieved 5 November 2014.

- Lodge, Barton, ed. (1879). Palladius on Husbondrie (From the unique MS. of about 1420 AD in Colchester Castle for the Early English Text Society ed.). London: N. Trübner & Co. Retrieved 27 November 2014.

Eighteenth and Nineteenth century

- Linnaeus, Carl (1829). Schultes, Josef August; Schultes, Julius Hermann, eds. Systema vegetabilium. Stuttgardt: J. G. Cottae. Retrieved 25 October 2014.

- Linné, Carl von (1784). Murray, Johann Andreas, ed. Systema vegetabilium (14th edition of Systema Naturae). Typis et impensis Jo. Christ. Dieterich. Retrieved 3 November 2014.

- Barr, Peter; Burbidge, F.W. (1884). Ye Narcissus Or Daffodyl Flowere, Containing Hys Historie and Culture, &C., With a Compleat Liste of All the Species and Varieties Known to Englyshe Amateurs. London: Barre & Sonne. ISBN 978-1104534271. Retrieved 2 November 2014.

- A. P. de Candolle (1813). Théorie élémentaire de la botanique, ou exposition des principes de la classification naturelle et de l'art de décrire et d'etudier les végétaux. Retrieved 5 February 2014.

- De Lamarck, Jean-Baptiste; De Candolle, Augustin Pyramus (1815a). Flore française ou descriptions succinctes de toutes les plantes qui croissent naturellement en France disposées selon une nouvelle méthode d'analyse ; et précédées par un exposé des principes élémentaires de la botanique (vol. III) (3 ed.). Paris: Desray. Retrieved 29 October 2014.

- De Lamarck, Jean-Baptiste; De Candolle, Augustin Pyramus (1815b). Flore française ou descriptions succinctes de toutes les plantes qui croissent naturellement en France disposées selon une nouvelle méthode d'analyse ; et précédées par un exposé des principes élémentaires de la botanique (vol. V) (3 ed.). Paris: Desray. Retrieved 29 October 2014.

- Redouté, Pierre Joseph; De Candolle, Augustin Pyramus (1805–1808). Les liliacées. Paris: Redouté. Retrieved 1 November 2014.

- Brown, Robert (1810). Prodromus florae Novae Hollandiae et Insulae Van-Diemen, exhibens characteres plantarum. London: Taylor. Retrieved 30 October 2014.

- Herbert, William (1837). Amaryllidaceae: Preceded by an Attempt to Arrange the Monocotyledonous Orders, and Followed by a Treatise on Cross-bred Vegetables, and Supplement. London: Ridgway. Retrieved 20 October 2014.

- Wilkes, John, ed. (1819). "Narcissus". Encyclopaedia Londinensis vol. 16. London. pp. 576–580. Retrieved 2 November 2014.

- Wilkinson, Caroline Catharine, Lady (1858). Weeds and wild flowers : their uses, legends, and literature. London: J. Van Voorst. Retrieved 26 November 2014.

- Salisbury, Richard Anthony; Gray, J. E. (1866). The Genera of Plants (Unpublished fragment.). Retrieved 26 October 2014.

- Burbidge, Frederick William (1875). The Narcissus: Its History and Culture: With Coloured Plates and Descriptions of All Known Species and Principal Varieties. London: L. Reeve & Company. Retrieved 28 September 2014. (also available as pdf)

- Prior, Richard Chandler Alexander (1870). On the popular names of British Plants, being an explanation of the origin and meaning of the names of our indigenous and most commonly cultivated species (2 ed.). London: Williams & Norgate. Retrieved 6 October 2014.

- Ellacombe, Henry Nicholson (1884). The Plant-lore & Garden-craft of Shakespeare (2 ed.). London: W Satchell and Co. Retrieved 26 November 2014.

Modern

- Webb, DA (1978). "Taxonomic notes on Narcissus L". Bot J Linn Soc 76 ((June) 4): 298–307. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8339.1978.tb01817.x. Retrieved 23 October 2014.

- Tutin, T. G.; et al., eds. (1980). Flora Europaea. Volume 5, Alismataceae to Orchidaceae (monocotyledones) (Reprinted ed.). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 052120108X. Retrieved 4 October 2014.

- Hanks, Gordon R (2002). Narcissus and Daffodil: The Genus Narcissus. London: Taylor and Francis. ISBN 0415273447. Retrieved 2 October 2014.

- ICN (2011). "International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants". Bratislava: International Association for Plant Taxonomy. Retrieved 2 February 2014.

- Aedo, Carlos (2010). "Typifications of the names of Iberian accepted species of Narcissus L. (Amaryllidaceae)" (PDF). Acta Botanica Malacitana 35: 133–142. Retrieved 29 November 2014.

Societies and organisations

- "Narcissus". Pacific Bulb Society. 2014. Retrieved 29 December 2014.

- "Overview of the Narcissus Species". Pacific Bulb Society. 2014. Retrieved 29 December 2014.

| External identifiers for Narcissus | |

|---|---|

| Encyclopedia of Life | 29121 |

| GBIF | 2858200 |

| ITIS | 500435 |

| NCBI | 4697 |

| Also found in: Wikispecies, Tropicos | |