Tarkine

| Tarkine Tasmania | |

|---|---|

The Tarkine is an area in the north-west of Tasmania |

The Tarkine (indigenous name: takayna) is an area of the north west Tasmania, Australia, which environmental non-government organisations (ENGOs) claim contains significant areas of wilderness.[1] The Tarkine is noted for its beauty and natural values, containing the largest area of Gondwanan cool-temperate rainforest in Australia,[2][3] as well as for its prominence in Tasmania's early mining history.[4][5][6][7] The area's high concentration of Aboriginal sites has led to it being described by the Australian Heritage Council as "one of the world's great archaeological regions".[8]

Location

The Tasmanian government defines the Tarkine as an "unbounded locality" centred in the Waratah-Wynyard council area.[9] The generally accepted definition is the area between the Arthur River in the North, the Pieman River in the south, the ocean to the west and the Murchison Highway in the east.[10] [11] It was first officially recognised in May, 2013, following a recommendation by the Nomenclature Board of Tasmania which was accepted by Bryan Green. He declared that the name applied to the whole north-west region of Tasmania,[12] but this interpretation was rejected by the Cradle Coast Authority, which had requested the official naming.[13] [14] The name does not appear in maps, but in recent decades has featured prominently in the Australian media as a subject of contention between conservationists and mining/logging interests.[15]

The Tarkine can be entered from several points, with the most common being via Sumac Road from the north, Corinna in the south, Waratah in the west and Wynyard from the north-east. Wynyard has an interstate airport and sealed road access into the Tarkine.

Etymology

The name "Tarkine" was coined by the conservation movement [16] and was in use by 1991.[17] It is a diminutive of the name "Tarkiner", [18] which is the anglicised pronunciation of one of the Aboriginal tribes who inhabited the western Tasmanian coastline from the Arthur River to the Pieman River before European colonisation.

Natural and archaeological values

The Tarkine contains extensive high-quality wilderness as well as extensive, largely undisturbed tracts of cool temperate rainforest which are extremely rare.[19][20] It also represents Australia's largest remaining single tract of temperate rainforest.[1] It contains approximately 1,800 km² of rainforest, around 400 km² of eucalypt forest and a mosaic of other vegetation communities, including dry sclerophyll forest, woodland, buttongrass moorland, sandy littoral communities, wetlands, grassland and Sphagnum communities. Significantly, it has a high diversity of non-vascular plants (mosses, liverworts and lichens) including at least 151 species of liverworts and 92 species of mosses. Its range of vertebrate fauna include 28 terrestrial mammals, 111 land and freshwater birds, 11 reptiles, 8 frogs and 13 freshwater fish. The Tarkine provides habitat for over 60 rare, threatened and endangered species of flora and fauna.[1]

The area comprises a number of rivers, exposed mountains, globally unique magnesite and dolomite cave systems and the largest basalt plateau in Tasmania to have retained its original vegetation.[1]

There are also large sand dune areas extending several kilometres inland. Some of these contain ancient Aboriginal middens.

The Tarkine played a central role in the development of Tasmania's early mining industry, and remains of early mining activity can still be seen in many rivers and creeks in the area that were mined for gold, tin and osmiridium.[4][5][6] Nowadays the remains of approximately 600 sites of historic mining activity in the area are still evident.[21] The majority of these mining operations were alluvial workings or small hard-rock mines, consisting often of single adits. Larger scale mining has been carried out mainly at Luina, Savage River and Mt Bischoff. Part of the area is contained in the Arthur – Pieman Conservation Area managed by the Tasmania parks and wildlife service.

Early conservation movement

The campaign to protect the Tarkine began in the 1960s. A formal conservation proposal was put forward by the then Circular Head Mayor Horace Jim Lane for the establishment of a 'Norfolk Range National Park'. Lane's proposal was not realised.

From the late 1990s, the area came under increasing national and international scrutiny in a similar vein to the environmental protests surrounding Tasmania's Franklin River and Queensland's Daintree Rainforest. The case for protecting the Tarkine was significantly advanced with the Federal Government's Forestry Package in 2005 adding 70,000 hectares to reserves in the Tarkine.

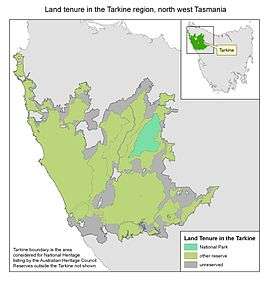

Around 80% of the Tarkine is now in conservation reserves, however recent changes to Tasmanian legislation allow logging to occur in the majority of those reserves. Only 5% is protected from mining.

Proposed Tarkine National Heritage listing

In December 2009, the Tarkine was listed as a National Heritage Area following an Emergency National Heritage Listing. The Emergency Listing was in response to a proposed Tarkine Road, which would have coursed through old growth forest and detrimentally affected the natural values of undisturbed areas. In December 2010, the incoming Environment Minister Tony Burke allowed the emergency listing to lapse in the face of numerous mining proposals in the Tarkine. This was despite recommendations from the Australian Heritage Council to permanently list the Tarkine. Minister Burke has further extended the period for reassessment of the Tarkine, with the Australian Heritage Council now due to re-report on the suitability of the Tarkine as a National Heritage location by the end of December 2013. Conservation groups have declared this an unacceptable delay, and have voiced concerns that this leaves the Tarkine unprotected from mining while the reassessment takes place.

On 8 February 2013 Minister Tony Burke announced that he would reject advice from the Australian Heritage Council that 433,000 hectares should be heritage listed and instead apply a National Heritage Listing only to the 21,000 hectares contained in a 2 km wide section along the coastline.[22]

Proposed Tarkine National Park

The environmentalist organisation Tarkine National Coalition, headed by Scott Jordan, proposed the Tarkine be officially declared a national park.[23] However, the process of securing such a declaration has been complicated by the processes of the Tasmanian Forests Intergovernmental Agreement.[24] This legislation was signed on 7 August 2011 by Australian Prime Minister Julia Gillard and Tasmanian Premier Lara Giddings. The agreement established a $276 million package to transition Tasmania out of native forest logging, while conserving large areas of high conservation value vegetation. Julia Gillard stated that the Agreement would better protect the Tarkine, describing the wilderness area as "very important".[25]

Subsequent related state legislation (the Tasmanian Forests Agreement Bill 2013) passed through the Tasmanian House of Assembly on 23 November 2012[26] and then passed to the Tasmanian Legislative Council where it was debated and referred on to a Select Committee.[27] It was ultimately passed on 30 April 2013. The Hobart Mercury noted that "Despite a raft of controversial amendments from the Upper House, all but one of the Tasmanian Greens MPs supported the Bill in the Lower House"[28]

Following a change in Tasmanian state government, the Tasmanian Forests Agreement reserves were rescinded in 2014, and previous reserves were made available for 'specialty timber' logging. 'Specialty timber' includes rainforest species such as celery top pine, sassafras, blackwood, myrtle and even eucalypts. This effectively renders the reserve estate in the Tarkine toothless, with the exception of the Savage River National Park covering just 5% of the Tarkine area.

The campaign for a Tarkine National Park continues.

Mining in the Tarkine

The areas of Corinna [29] - Long Plains,[30] as well as the Savage, Donaldson[31] and Whyte[4] rivers were important early goldfields, exploited since the 1870s, and Tasmania's two largest gold nuggets, of 7.6 and 4.4 kg, were found near the confluence of the Whyte and Rocky rivers.[4] Tin mining was prominent in both the Mt Bischoff - Waratah area[7] starting in the 1870s, as well as the Meredith Range - Stanley River - Wilson River area.[6] The Mt. Bischoff mine in Waratah was in its heyday one of the richest tin deposits in the world.[32] From the 1880s onwards, osmiridium was extensively mined in many creeks and rivers in the catchments of the Savage, Haezlewood and Wilson rivers,[5] and particularly the Bald Hill area.[33] Tin, copper and tungsten were mined at Balfour,[34] and the Magnet mine was exploited for silver since the 1890s,[35] and continues to be an important amateur fossicking area for mineral specimens to this day.[36]

Historically, approximately 600 mine tenements have been worked in the Tarkine area,[37] however most of these tenements being small alluvial workings consisting of sifting gravels from riverbeds. Mining activity in the Tarkine has continued uninterrupted since the 1870s, and two modern industrial mines are currently operating in the area: a small silica quarry, and a large open cut iron ore mine at Savage River.Both these existing mines are outside of the proposed Tarkine National Park boundary. In addition, 38 exploration licenses are currently held over areas of the Tarkine, and 10 mines have been proposed over the 2012-2017 period. Of these proposed mines, nine are proposed to be open cut mines. The issue of mining in the Tarkine is highly contentious, as conservationists oppose the environmental damage caused by modern mining methods. The Tarkine is highly prospective for economically-important minerals,[16] and proponents argue that current and proposed mines would take up just 1% of the Tarkine.[38] Conservationists argue that this impact is greater when considering transport routes and damage to water catchments. They point to the acid mine drainage affecting the Whyte River, rendering it orange stained and devoid of aquatic life for six kilometres following the now closed Cleveland mine at Luina, and similar impacts downstream from historic operations of the Savage River mine and the closed Mt Bischoff mine. Acid mine drainage (AMD) is the leaching of sulphuric acid, caused by the chemical reaction between sulphides in the ore and oxygen that can occur once ore is exposed to atmosphere. Start-up mining company Venture Minerals have proposed three open cut mines within the existing reserves and moratorium area, with plans to explore over an additional 37 km of ore bearing skarn mostly in reserves.

Conservation groups such as the Tarkine National Coalition and Operation Groundswell oppose new mines and mining exploration in the Tarkine and are warning of a campaign to surpass the Franklin River campaign of the 1980s. Alternatively, significant local support for mining has also been evidenced, with over 3500 people attending one pro-development rally[39] and the mayors of the four affected council areas publicly condemning the environmental groups.[40][41]

References

- 1 2 3 4 "Tasmanian Forest Agreement Verification: Advice to Prime Minister and Premier of Tasmania Interim Reserve Boundaries" (PDF). Government of Tasmania. Retrieved 19 March 2013.

- ↑ "The Tarkine national heritage assessment" (PDF). Australian Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities. Retrieved 19 March 2013.

- ↑ "Tarkine ecological facts and statistics". WWF. Retrieved 19 March 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 "Gold in Tasmania" (PDF). Mineral Resources Tasmania. Retrieved 16 May 2013.

- 1 2 3 "Osmiridium in Tasmania" (PDF). Mineral Resources Tasmania. Retrieved 16 May 2013.

- 1 2 3 "The Stanley River Tin Field" (PDF). Mineral Resources Tasmania. Retrieved 16 May 2013.

- 1 2 "The Mount Bischoff Tin Field" (PDF). Mineral Resources Tasmania. Retrieved 16 May 2013.

- ↑ Richards, Thomas; Sutherland-Richards, Phillipa (1992). "Archaeology". In: Harries, D.N. (editor). Forgotten Wilderness: North-West Tasmania. A Report to the Australian Heritage Commission. Hobart: Tasmanian Conservation Trust.

- ↑ "List map". Tasmanian Government. Search for Tarkine. Retrieved 6 June 2013.

- ↑ Siobhan Maiden (13 May 2009). "Where is the Tarkine?". ABC News.

- ↑ Eliza Wood (27 October 2011). "A week in the west: the Tarkine". ABC Rural.

- ↑ Sean Ford (31 May 2013). "Tarkine officially covers most of NW and West". The Advocate.

- ↑ Sean Ford (25 June 2013). "Calls for Green to admit he got it wrong". The Advocate.

- ↑ Mark Acheson (1 June 2013). "Tarkine knows no boundaries: Jaensch". The Advocate.

- ↑ "Tarkine protest halts iron mine". The Mercury. 11 May 2013. Retrieved 17 May 2013.

- 1 2 "Tarkine a question of values: mines versus ancient rainforest". University of Tasmania. Retrieved 17 May 2013.

- ↑ Friends of the Earth Australia (1991). Chain Reaction Issues 63-72. Friends of the Earth Australia.

- ↑ George Augustus Robinson described his meetings with Tarkiner Aborgines in his 1829-1834 diaries.

- ↑ Hitchcock, P. "Verification of the Heritage Value of ENGO-Proposed Reserves" (PDF). IVG Forest Conservation Report 5A. Retrieved 2013-02-26.

- ↑ "Tarkine World Heritage Values Summary". Australian Government. Retrieved 2013-02-26.

- ↑ http://www.tasmanianmining.com.au/mining_people/nic_haygarth_plenty_of_mining_fodder_for_this_tasmanian_story_teller

- ↑ "Press Conference - Tarkine National Heritage Listing". Australian Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities. 8 February 2013.

- ↑ "Tarkine National Park". Tarkine National Coalition. Retrieved 13 April 2013.

- ↑ "Tasmanian Forests Intergovernmental Agreement between the Commonwealth of Australia and the State of Tasmania" (PDF). Australian Government. 7 August 2011.

- ↑ Yard, Annah (7 August 2011). "Gillard signs off on Tasmanian forest deal". ABC News.

- ↑ "Legislation Passed Through House of Assembly". The Department of Infrastructure, Energy and Resources. Retrieved 13 April 2013.

- ↑ "Tasmanian Forest Agreement Update". The Department of Infrastructure, Energy and Resources. Retrieved 13 April 2013.

- ↑ "Peace, (im)perfect peace". 1 May 2013. Retrieved 1 May 2013.

- ↑ "Report on the Corinna Goldfield" (PDF). Mineral Resources Tasmania. Retrieved 16 May 2013.

- ↑ "Report on Mineral Fields between Waratah and Long Plains" (PDF). Mineral Resources Tasmania. Retrieved 16 May 2013.

- ↑ "Diamonds in Tasmania" (PDF). Mineral Resources Tasmania. Retrieved 16 May 2013.

- ↑ "Mt Bischoff mine, Waratah, Waratah district, Tasmania, Australia". Mindat.org. Retrieved 16 May 2013.

- ↑ "The Bald Hill Osmiridium Field" (PDF). Mineral Resources Tasmania. Retrieved 16 May 2013.

- ↑ "The Mount Balfour Mining Field" (PDF). Mineral Resources Tasmania. Retrieved 16 May 2013.

- ↑ "HISTORY OF MAGNET MINE" (PDF). Mineral Resources Tasmania. Retrieved 16 May 2013.

- ↑ "MAGNET MINE FOSSICKING AREA". Mineral Resources Tasmania. Retrieved 16 May 2013.

- ↑ "Nic Haygarth: plenty of mining fodder for this Tasmanian historian". Tasmanian Mining. Retrieved 19 March 2013.

- ↑ http://www.theadvocate.com.au/story/380167/devising-right-plan-for-tarkine-is-a-balancing-act/

- ↑ Kempton, Helen (18 November 2012). "Tarkine row at boiling point". The Mercury.

- ↑ "Council takes on Tarkine Coalition". ABC News. 19 September 2012.

- ↑ "Council’s issue joint response to Tarkine campaign" (PDF). Waratah Wynyard Council. 14 February 2013.

External links

- Road to Nowhere A review of the video "Manifestations" about protests that took place in the Tarkine in 1994/95.