Talysh-Mughan Autonomous Republic

| Talysh-Mughan Autonomous Republic | |||||

| Toлъш-Mоғонә Mоxтaрә Рeспубликә | |||||

| Unrecognized state | |||||

| |||||

|

| |||||

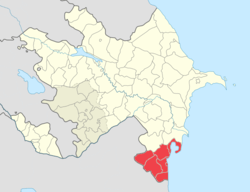

Location of the Talysh-Mughan Autonomous Republic in Azerbaijan. | |||||

| Capital | Lenkaran (largest city) | ||||

| Languages | Talysh · Azerbaijani | ||||

| Religion | Islam | ||||

| Government | Republic | ||||

| President | |||||

| • | 1993 | Alikram Hummatov | |||

| Historical era | Post-Cold War | ||||

| • | Established | 21 June 1993 | |||

| • | Disestablished | 23 August 1993 | |||

| Today part of | | ||||

The Talysh-Mughan Autonomous Republic (Azerbaijani: Talış-Muğan Muxtar Respublikası, Talysh: Toлъш-Mоғонә Mоxтaрә Рeспубликә) was a short-lived self-proclaimed separatist autonomous republic in Azerbaijan, that lasted from June to August 1993.[1] It was located in extreme southeastern Azerbaijan, envisaging to consist in the 7 administrative districts of Azerbaijan around the regional capital city Lankaran: Lankaran, Lankaran rayon, Lerik, Astara, Masally, Yardymli. Historically the area had been a khanate.

Political turmoil

The autonomous republic was proclaimed amid political turmoil in Azerbaijan, with the tacit support from Russia. In June 1993 a military rebellion against president Abulfaz Elchibey broke out under the leadership of Colonel Surat Huseynov. Colonel Alikram Hummatov (Alikram Gumbatov), a close associate of Huseynov, and the leader of the Talysh nationalists, seized power in the southern part of Azerbaijan and proclaimed the new republic in Lankaran, escalating violence. However, as the situation settled and Heydar Aliyev rose to power in Azerbaijan, the Talysh-Mughan Autonomous Republic, which failed to gain any significant public support, was swiftly suppressed.[2]

Alikram Hummatov had to flee Lenkoran, when an estimated 10,000 protesters gathered outside his headquarters in the city to demand his ouster.[3]

According to Professor Bruce Parrott,

| “ | This adventure rapidly turned into farce. The Talysh character of the "republic" was minimal, while the clear threat to Azerbaijani territorial integrity posed by its mere existence only discredited Gumbatov and, by association, Guseinov.[4] | ” |

Some observers believe that this revolt was part of a larger conspiracy to bring back to power the former president Ayaz Mütallibov.[5][6]

Hummatov was arrested and initially received death sentence which was subsequently commuted to life imprisonment. In 2004 he was pardoned and released from custody under pressure from the Council of Europe. He was allowed to immigrate to Europe after making a public promise not to engage in politics. However, those who were involved in proclamation of the autonomy say they always envisaged the autonomous republic as a constituent part of Azerbaijan.[1]

Ethnic status

According to some, the Azerbaijani government has also implemented a policy of forceful integration of some minorities, including Talysh, Tat, Kurds and Lezgins.[7] However, according to a 2004 resolution of Council of Europe:

| “ | Azerbaijan has made particularly commendable efforts in opening up the personal scope of application of the Framework Convention to a wide range of minorities. In Azerbaijan, the importance of the protection and promotion of cultures of national minorities is recognised and the long history of cultural diversity of the country is largely valued;[8] | ” |

IFPRERLOM appealed to the Commission on Human Rights for the purpose of adopting a resolution, which urges Azerbaijan to guarantee the preservation of the cultural, religious and national identity of the Talysh people in light of repeated claims of repression.[9]

See also

References

- 1 2 BBC News. Azerbaijan in a stir over political prisoner

- ↑ Vladimir Socor. «Talysh issue, dormant in Azerbaijan, reopened in Armenia», The Jamestown Foundation, May 27, 2005

- ↑ The New York Times, 24.08.1993. Pro-Iranian is ousted

- ↑ Bruce Parrott. State Building and Military Power in Russia and the New States of Eurasia. M.E. Sharpe, 1995. ISBN 1-56324-360-1, ISBN 978-1-56324-360-8

- ↑ Humbatov received the support of former defense minister Rahim Gaziev and swore loyalty to former president Mutalibov. This revolt, which collapsed in August with almost no bloodshed, appeared to be part of the same larger design as Hussienov’s rebellion in Ganje. Thomas De Waal, Black Garden: Armenia and Azerbaijan through Peace and War, NYU Press, 2004

- ↑ One likely scenario is that this episode was another example of a powerful local warlord attempting to take advantage of the internal instability within Azerbaijan, on this occasion by appealing to ethnic Persian sentiment. Gummatov had previously benefited under Mutalibov and appears to have borne a grudge against Aliev. There are reports that the rebel colonel had at one time demanded as a price for the end of his rebellion the resignation of Aliev and the return to power of Mutalibov. Alvin Z. Rubinstein, Oles M. Smolansky. Regional Power Rivalries in the New Eurasia: Russia, Turkey, and Iran. M.E. Sharpe, 1995. ISBN 1-56324-623-6, ISBN 978-1-56324-623-4

- ↑ Christina Bratt (EDT) Paulston, Donald Peckham, Linguistic Minorities in Central and Eastern Europe, Multilingual Matters. 1853594164, pg 106

- ↑ Council of Europe, Committee of Ministers, Resolution ResCMN-2004-8, on the implementation of the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities by Azerbaijan, Adopted by the Committee of Ministers on 13 July 2004 at the 893rd meeting of the Ministers Deputies.

- ↑