Tactical voting

In voting systems, tactical voting (or strategic voting or sophisticated voting or insincere voting) occurs, in elections with more than two candidates, when a voter supports a candidate other than his or her sincere preference in order to prevent an undesirable outcome.[1]

It has been shown by the Gibbard–Satterthwaite theorem that, if a voting method for choosing one of several options is completely strategy-free, then it must be either dictatorial or nondeterministic (that is, might not select the same outcome every time it is applied to the same set of voter preferences). For instance, the random ballot voting method, which randomly selects the ballot of a single voter and uses this to determine the outcome, is strategy-free, but may result in different choices being selected if applied multiple times to the same set of ballots.

For example, in a simple plurality election, a voter might sometimes gain a "better" outcome by voting for a less preferred but more generally popular candidate.

However, the type of tactical voting and the extent to which it affects the character of the campaign and the results of the election vary dramatically from one voting system to another.

Types

Compromising

Compromising (sometimes "useful vote") is a type of tactical voting in which a voter insincerely ranks an alternative higher in the hope of getting it elected. For example, in the first-past-the-post election, voters may vote for an option they perceive as having a greater chance of winning over an option they prefer (e.g., a conservative voter voting for an uncontroversial moderate candidate over a controversial right-wing candidate in order to help defeat a popular leftist candidate.) Duverger's law suggests that, for this reason, first-past-the-post election systems will lead to two-party systems in most cases. In those proportional representation systems that include a minimum percentage of votes that a party must achieve to receive any seats, people might vote tactically for a minor party to prevent it from dropping below that percentage (which would make the votes it does receive useless for the larger political camp that party belongs to), or alternatively those who support the viewpoints of a minor party may vote for the larger party whose views are closest to those of the minor party.

Burying

Burying is a type of tactical voting in which a voter insincerely ranks an alternative lower in the hopes of defeating it. For example, in the Borda count or in a Condorcet method, a voter may insincerely rank a perceived strong alternative last in order to help his or her preferred alternative beat it.

Push-over

Push-over (also called mischief voting) is a type of tactical voting in which a voter ranks a perceived weak alternative higher, but not in the hopes of getting it elected. This primarily occurs in runoff voting when a voter already believes that their favored candidate will make it to the next round – the voter then ranks an unpreferred, but easily beatable, candidate higher so that their preferred candidate can win later.[2] In the United States, for instance, voters of one party sometimes vote in the other party's primary to nominate a candidate who will be easy for their favorite to beat, especially after that favorite has secured their party's own nomination.

Bullet voting

Bullet voting is when a voter votes for just one candidate, despite having the option to vote for more than one due to a voting system such as approval voting or plurality-at-large voting. A voter helps his or her preferred candidate by not supplying votes to potential rivals. This strategy is encouraged and seen as sometimes beneficial in the systems of limited voting and cumulative voting.

Examples in real elections

United States

One high-profile example of tactical voting was the California gubernatorial election, 2002. During the Republican primaries, Republicans Richard Riordan (former mayor of Los Angeles) and Bill Simon (a self-financed businessman) were vying for a chance to compete against the unpopular incumbent Democratic Governor of California, Gray Davis. Polls predicted that Riordan would defeat Davis, while Simon would not.

At that time, the Republican primaries were open primaries in which anyone could vote regardless of her or his own party affiliation. Davis supporters were rumored to have voted for Simon because Riordan was perceived as a greater threat to Davis; this combined with a negative advertising campaign by Davis describing Riordan as a "big-city liberal", and Simon ultimately won the primary despite a last-minute business scandal. However, he lost the election against Davis; discontent soon led to the recall.

United Kingdom

In the 1997 UK general election, Democratic Left helped Bruce Kent set up GROT - Get Rid Of Them - a tactical voter campaign whose sole aim was to help prevent the Conservative Party from gaining a 5th term in office. This coalition was drawn from individuals in all the main opposition parties and many who were not aligned with any party. While it would be hard to prove that GROT swung the election itself, it did attract significant media attention and brought tactical voting into the mainstream for the first time in UK politics. In 2001, the Democratic Left's successor organisation the New Politics Network organised a similar campaign tacticalvoter.net. Since then tactical voting has become a real consideration in British politics as is reflected in by-elections and by the growth in sites such as tacticalvoting.com who encourage tactical voting as a way of defusing the two party system and empowering the individual voter. In the 2005 UK General Election individuals set up tacticalvoting.net to balance the tactical voting debate. For the 2015 UK general election, http://voteswap.org was set up to help prevent the Conservative Party staying in government, by encouraging Green Party supporters to tactically vote for the Labour Party in listed marginal seats.

In the 2006 local elections in London, tactical voting is being promoted by sites such as London Strategic Voter in a response to national and international issues. The question of whether this approach acts to undermine local democracy is receiving much debate.

In Northern Ireland, it is widely believed that (predominantly Protestant) Unionist voters in Nationalist strongholds have voted for the Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP) to prevent Sinn Féin from capturing such seats. This conclusion was reached by comparing results to the demographics of constituencies and polling districts.

Canada

In the Ontario general election, 1999, strategic voting was widely encouraged by opponents of the Progressive Conservative government of Mike Harris. This failed to unseat Harris, and succeeded only in suppressing the New Democratic Party vote to a historic low.

In the Canadian general election, 2004 and to a lesser extent in the Canadian general election, 2006, strategic voting was a concern for the federal New Democratic Party. In the 2004 election, the governing Liberal Party was able to convince many New Democratic voters to vote Liberal in order to avoid a Conservative government. In the 2006 elections, the Liberal Party attempted the same strategy, with Prime Minister Paul Martin asking New Democrats and Greens to vote for the Liberal Party in order to prevent a Conservative win. The New Democratic Party leader Jack Layton would respond by asking voters to "lend" their votes to his party, suggesting that the Liberal Party would be bound to lose the election regardless of strategic voting.

During the Canadian general election, 2015, strategic voting has become more vocal as anti-Conservative campaigners canvassed voters door to door. Almost all strategic voting (websites and activists) is aimed at the Conservative party not winning seats.[3][4]

Other countries

In Hong Kong, with its largest remainder method with the Hare quota, voters supporting candidates of the pro-democracy camp will organise to cast their votes to different tickets, so as to avoid votes being concentrated on one or a few candidates and wasted.[5]

Puerto Rico's 2004 elections were affected by tactical voting. The New Progressive Party's candidate was unpopular, except among the pro-statehood Right, because of large corruption schemes and privatization of public corporations. To prevent him from winning, other factions supported the Partido Popular Democratico's candidate. The elections were close; statehood advocates won a seat in the U.S. house of representatives and majorities in both legislative branches, but lost governance to Anibal Acevedo Vila. (In Puerto Rico you have the chance to vote by party or by candidate. Separatists voted under their ideology, but for the center party's candidate. This caused major turmoil.) After a recount and a trial, Anibal Acevedo Vila was certified as governor of the commonwealth of Puerto Rico.

In 2011 Slovenian parliamentary election, 30% of voters voted tactically. Public polls predicted easy win for Janez Janša, the candidate of the Slovenian Democratic Party, however his opponent Zoran Janković, the candidate of Positive Slovenia won. According to prominent Slovenian public opinion researchers, such proportions of tactical voting were not recorded anywhere else before.[6]

Rational voter model

Academic analysis of tactical voting is based on the rational voter model, derived from rational choice theory. In this model, voters are short-term instrumentally rational. That is, voters are only voting in order to make an impact on one election at a time (not, say, to build the political party for next election); voters have a set of sincere preferences, or utility rankings, by which to rate candidates; voters have some knowledge of each other's preferences; and voters understand how best to use tactical voting to their advantage. The extent to which this model resembles real-life elections is the subject of considerable academic debate.

Myerson-Weber strategy

An example of a rational voter strategy is described by Myerson and Weber.[7] The strategy is broadly applicable to a number of single-winner voting systems that are additive point systems, such as Plurality, Borda, Approval, and Range. The strategy is optimal in the sense that the strategy will maximize the voter's expected utility when the number of voters is sufficiently large.

This rational voter model assumes that the voter's utility of the election result is dependent only on which candidate wins and not on any other aspect of the election, for example showing support for a losing candidate in the vote tallies. The model also assumes the voter chooses how to vote individually and not in collaboration with other voters.

Given a set of k candidates and a voter let:

- vi = the number of points to be voted for candidate i

- ui = the voter's gain in utility if candidate i wins the election

- pij = the (voter's perceived) pivot probability that candidates i and j will be tied for the most total points to win the election.

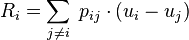

Then the voter's prospective rating for a candidate i is defined as:

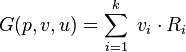

The gain in expected utility for a given vote is given by:

The gain in expected utility can be maximized by choosing a vote with suitable values of vi, depending on the voting system and the voter's prospective ratings for each candidate. For specific voting systems, the gain can be maximized using the following rules:

- Plurality: Vote for the candidate with the highest prospective rating. This is to be distinguished from choosing the best of the frontrunners, which is a common but imprecise plurality tactic. The highest prospective rating can in fact belong to a weak candidate, even the weakest.

- Borda: Rank the candidates in decreasing order of prospective rating.

- Approval: Vote for all candidates that have a positive prospective rating; do not vote for any candidates that have a negative prospective rating.

- Range: Vote the maximum points for all candidates that have a positive prospective rating; vote the minimum allowed value for all candidates that have a negative prospective rating; vote any number of points for a candidate with a prospective rating of zero.

An important special case occurs when the voter has no information about how other voters will vote. This is sometimes referred to as the zero information strategy. In this special case, the pij pivot probabilities are all equal and the rules for the specific voting systems become:

- Plurality: Vote for the most preferred (highest utility) candidate. This is the sincere plurality vote.

- Borda: Rank the candidates in decreasing order preference (decreasing order of utility). This is the sincere ranking of the candidates.

- Approval: Calculate the average utility of all candidates. Vote for all candidates that have a higher-than-average utility; do not vote for any candidates that have a lower-than-average utility.

- Range: Calculate the average utility of all candidates. Vote the maximum points for all candidates that have a higher-than-average utility; vote the minimum points for all candidates that have a lower-than-average utility; vote any value for a candidate with a utility equal to the average.

Myerson and Weber also describe voting equilibria that require all voters use the optimal strategy and all voters share a common set of pij pivot probabilities. Because of these additional requirements, such equilibria may in practice be less widely applicable than the strategies.

Pre-election influence

Because tactical voting relies heavily on voters' perception of how other voters intend to vote, campaigns in electoral systems that promote compromise frequently focus on affecting voter's perception of campaign viability. Most campaigns craft refined media strategies to shape the way voters see their candidacy. During this phase, there can be an analogous effect where campaign donors and activists may decide whether or not to support candidates tactically with their money and labor.

In rolling elections, or runoff votes, where some voters have information about previous voters' preferences (e.g. presidential primaries in the United States, French presidential elections), candidates put disproportionate resources into competing strongly in the first few stages, because those stages affect the reaction of later stages.

Views on tactical voting

Some people view tactical voting as providing misleading information. In this view, a ballot paper is asking the question "which of these candidates is the best?". This means that if one votes for a candidate who one does not believe is the best, then one is lying. British Labour Party politician Anne Begg said of tactical voting:

- "Tactical voting is fine in theory and as an intellectual discussion in the drawing room or living rooms around the country, but when you actually get to polling day and you have to vote against your principles, then it is much harder to do."

Tactical voting is commonly regarded as a problem, since it makes the actual ballot into a nontrivial game, where voters react and counter-react to what they expect other voters' strategies to be. A game such as this might even result in a worse alternative being chosen, because most of the voters used it as a strategic tool. However the existence of limited tactical voting can be thought to increase the quality of the candidates elected because it takes into account not just the "ranking" of the candidates but also the utilities.

Though Arrow's impossibility theorem and Gibbard-Satterthwaite theorem prove that any useful single-winner voting system based on preference ranking is prone to some kind of manipulation, some use game theory to search for some kind of "minimally manipulatable" (incentive compatibility) voting schemes.

Game theory can also be used to analyze the pros and cons of different methods. For instance, under purely honest voting, Condorcet method-like systems tend to settle on compromise candidates, while Instant-Runoff Voting favors those candidates which have strong core support - who may often be more extremist. An electorate using one of these two systems but which (in the general or the specific case) preferred the characteristics of the other system could consciously use strategy to achieve a result more characteristic of the other system. Under Condorcet, they may be able to win by "burying" the compromise candidate (although this risks throwing the election to the opposing extreme); while under IRV, they could always "compromise". It could be argued that in this case the option to vote tactically or not actually helps the electorate express its will, not only on which candidate is better, but on whether compromise is desirable. (This never applies to "sneakier" tactics such as push-over.)

Tactical voting greatly complicates the comparative analysis of voting systems. If tactical voting were to become significant, the perceived "advantages" of a given voting system (that is, tending towards compromise or favoring core support) could turn into disadvantages - and, more surprisingly, vice versa.

Influence of voting system

Tactical voting is highly dependent on the voting system being used. A tactical vote which improves a voter's satisfaction under one system could make no change or lead to a less-satisfying result under another system.

Moreover, although by the Gibbard-Satterthwaite theorem no deterministic single-winner voting system is immune to tactical voting in all cases, some systems' results are more resistant to tactical voting than others'. M. Badinski and R. Laraki, the inventors of the majority judgment system, performed an initial investigation of this question using a set of Monte Carlo simulated elections based on the results from a poll of the 2007 French presidential election which they had carried out using rated ballots. Comparing range voting, Borda count, plurality voting, approval voting with two different absolute approval thresholds, Condorcet voting, and majority judgment, they found that range voting had the highest (worst) strategic vulnerability, while their own system majority judgment had the lowest (best).[8] Further investigation would be needed to be sure that this result remained true with different sets of candidates.

In particular systems

Plurality voting

Tactical voting by compromising is exceedingly common in plurality elections. The most typical tactic is to assess which two candidates are frontrunners (most likely to win) and to vote for the preferred one of those two, even if a third candidate is preferred over both. In fact, Duverger's law states that this kind of tactical voting, along with the spoiler effect which can arise when such tactics are not used, will be so common that any system based on plurality will eventually result in two-party domination. Although this "law" is just an empirical observation rather than a mathematical certainty, it is generally supported by the evidence.

Due to the especially deep impact of tactical voting in such a system, some argue that systems with three or more strong or persistent parties become in effect forms of disapproval voting, where the expression of disapproval in order to keep an opponent out of office overwhelms the expression of approval to elect a desirable candidate.

Party-list Proportional Representation

The presence of an electoral threshold (typically at around 5% or 4%) can lead to voters voting tactically for a different party to their preferred political party (which may be more hardline or more moderate) in order to ensure that the party passes the threshold. An alliance of parties can fail to win a majority despite outpolling their rivals if one party in the alliance falls beneath the threshold. An example of this is the 2009 Norwegian election in which the right-wing opposition parties won more votes between them than the parties in the governing coalition, but the narrow failure of the Liberal Party to cross the 4% threshold led to the governing coalition winning a majority.

This effect has sometimes been nicknamed "Comrade 4%" in Sweden, where the electoral threshold is 4%, particularly when referring to supporters of the Social Democrats who vote tactically for the more hardline Left Party.[9][10] In the German federal election, 2013 the Free Democratic Party got only 4.8% of the votes so did not meet the 5% threshold. The party did not win any directly elected seats, so for the first time since 1949 was not represented in the Bundestag. Hence their ally the Christian Democratic Union had to form a grand coalition with the Social Democratic Party.

In several recent elections in New Zealand the National Party has suggested that National supporters in certain electorates should vote for minor parties or candidates who can win an electorate seat and would support a National government.This culminated in the Tea tape scandal when a meeting in the Epsom electorate in 2011 was taped. The meeting was to encourage National voters in the electorate to vote "strategically" for the ACT candidate; and it was suggested that Labour Party voters in the electorate should vote "strategically" for the National candidate as the Labour candidate could not win the seat but a National win in the seat would deprive National of an ally. The two major parties National and Labour always top up their electorate MPs with list MPs, so a National win in the seat would not increase the number of National MPs.

Even in countries with a low threshold such as the Netherlands, tactical voting can still happen for other reasons. In the campaign for the 2012 Dutch election, the Socialist Party had enjoyed good poll ratings, but many voters who preferred the Socialists voted instead for the more centrist Labour Party out of fear that a strong showing from the Socialists would lead to political deadlock. It was also suggested that a symmetrical effect on the right caused the Party for Freedom to lose support to the more centrist VVD[11]

Majority Judgment

In Majority Judgment, strategy is typically "semi-honest exaggeration." Voters exaggerate the difference between a certain pair of candidates but do not rank any less-preferred candidate over any more-preferred one. Even this form of exaggeration can only have an effect if the voter's honest rating for the intended winner is below that candidate's median rating or their honest rating for the intended loser is above it.

Typically, this would not be the case unless there were two similar candidates favored by the same set of voters. A strategic vote against a similar rival could result in a favored candidate winning; although if voters for both similar rivals used this strategy, it could cause a candidate favored by neither of these voter groups to win.

Balinski and Laraki argue that since under Majority Judgment, many voters have no opportunity to use strategy, in a test using simulated elections based on polling data, this system is the most strategy-resistant of the ones that the authors studied.

Approval voting

Similarly, in approval voting, unlike many other systems, strategy almost never involves ranking a less-preferred candidate over a more-preferred one.[12] However, strategy is in fact inevitable when a voter decides their "approval cutoff"; this is a variation of the compromising strategy. Overall, Steven Brams and Dudley R. Herschbach argued in a paper in Science magazine in 2001 that approval voting was the system least amenable to tactical perturbations. Meanwhile, Balinski and Laraki used rated ballots from a poll of the 2007 French presidential election to show that, if unstrategic voters only approved candidates whom they considered "very good" or better, strategic voters would be able to sway the result frequently, but that if unstrategic voters approved all candidates they considered "good" or better, approval was the second most strategy-resistant system of the ones they studied.[13]

One simple situation in which Approval strategy is important is if there is a close election between two similar candidates A and B and one distinct one Z, in which Z has 49% support. If all of Z's supporters approve just him, in hopes of him getting just enough to win, then supporters of A are faced with a tactical choice of whether to approve A and B (getting one of their preferred choices but having no say in which) or approving just A (possibly helping choose her over B, but risking throwing the election to Z). B's supporters face the same dilemma.

Range voting

In range voting, strategic voters who expect all other voters to be strategic will exaggerate their true preferences and use the same quasi-compromising strategy as in approval voting, above. That is, they will give all candidates either the highest possible or the lowest possible ranking. This presents an additional problem as compared to the approval system if some voters give honest "weak" votes with middle rankings and other voters give strategic approval votes. A strategic minority could overpower an honest majority. To minimize this problem, some range voting advocates suggest measures such as education or ballot design to encourage uninformed voters to give more-extreme rankings. A different path to minimize this problem is to use median scores instead of total scores, as median scores are less amenable to exaggeration, as in majority judgment.

However, if all voter factions have the same proportion of strategic and honest voters, simulations show that any significant proportion of honest voters will lead to results which tend to be more satisfying to voters than approval voting, and indeed, more satisfying than any other system with the same unbiased proportion of strategic voters.[14]

In a simulation study using polling data collected under a majority judgment system, that system's designers found that range voting was more vulnerable to strategy than any other system they studied, including plurality.[15]

Instant runoff voting

Instant runoff voting has less incentive for the compromising strategy than plurality and has a minor vulnerability to the push-over strategy. The bullet voting strategy is also entirely ineffective in IRV as that system satisfies the later-no-harm criterion.

Condorcet

Condorcet methods have a further-reduced incentive for the compromising strategy, but they have some vulnerability to the burying strategy. The extent of this vulnerability depends on the particular Condorcet method. Some Condorcet methods arguably reduce the vulnerability to burying to the point where it is no longer a significant problem. All guaranteed Condorcet methods are vulnerable to the bullet voting strategy, because they violate the later-no-harm criterion.

Borda

The Borda count has both a strong compromising incentive and a large vulnerability to burying. Here is a hypothetical example of both factors at the same time: if there are two candidates the most likely to win, the voter can maximize the impact on the contest between these candidates by ranking the candidate the voter likes more in first place, ranking the candidate whom they like less in last place. If neither candidate is the sincere first or last choice, the voter is using both the compromising and burying strategies at once. If many different groups voters use this strategy, this gives a paradoxical advantage to the candidate generally thought least likely to win.

Single Transferable Vote

The Single Transferable Vote has an incentive for free riding, a form of compromising strategy sometimes used in proportional representation systems. If one's top-choice candidate is elected, only a fraction of one's vote will be transferred to one's next-favoured candidate. If one feels the favoured candidate is certain to be elected in any case, insincerely ranking the second candidate first guarantees them a full vote if needed.[16] However, the greater the certainty of the first candidate being elected, the bigger their likely surplus, the higher the fraction of the vote that would be transferred to the next candidate, and hence the lower the proportionate benefit of tactical voting.

More sophisticated tactics may be practicable where the number of candidates, voters and/or seats to be filled is relatively small.

Some forms of STV allow tactical voters to gain an advantage by listing a candidate who is very likely to lose in first place, as a form of pushover.[17] Meek's method essentially eliminates this strategy.

Tactical unwind

The term "tactical unwind" is used by some political scientists and commentators to refer to the phenomenon when tactical voting takes place in one general election but in subsequent elections voters revert to their normal patterns.

See also

- Electoral fusion

- Keynesian beauty contest

- Political party

- Primary election

- Strategic nomination

- Tactical manipulation of runoff voting

- Unite the Right

- Vote allocation

- Vote swapping

References

- ↑ Farquharson, Robin (1969). Theory of Voting. Blackwell (Yale U.P. in the U.S.). ISBN 0-631-12460-8.

- ↑ Matthew S. Cook (March 2011). "Voting with Bidirectional Elimination" (PDF). Voting with Bidirectional Elimination. Retrieved 21 April 2012.

- ↑ http://www.huffingtonpost.ca/ken-wu/strategetic-voting-green_b_8305938.html

- ↑ http://www.cbc.ca/radio/thecurrent/the-current-for-october-15-2015-1.3271954/federal-election-2015-strategic-voters-challenge-democracy-1.3271971

- ↑ http://hkupop.hku.hk/english/columns/columns56.html

- ↑ "Raziskovalci o anketah: zmagalo taktično glasovanje" [Researchers on the Polls: Tactical Voting Won] (in Slovenian). Delo.si. 12 December 2011.

- ↑ Myerson, R. and Weber, R.J.(1993) A theory of Voting Equilibria. American Political Science Review Vol 87, No. 1. 102-114.

- ↑ Balinski M. and R. Laraki (2007) «Election by Majority Judgement: Experimental Evidence». Cahier du Laboratoire d’Econométrie de l’Ecole Polytechnique 2007-28. Chapter in the book: «In Situ and Laboratory Experiments on Electoral Law Reform: French Presidential Elections», Edited by Bernard Dolez, Bernard Grofman and Annie Laurent. Springer, to appear in 2011.

- ↑ Donald Granberg, Sören Holmberg (2010) «The Political System Matters: Social Psychology and Voting Behavior in Sweden and the United States (European Monographs in Social Psychology) ». Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ In Sweden, When the Voters Turn Right, the Right Turns Left

- ↑ Dutch vote ends resistible rise of radicals

- ↑ Such situations can only arise with more than 3 candidates. The only actual example known is a 6-way tie in which most voters only care which of three pairs of candidates the winner comes from, and a few voters only care which member of each pair wins. Smith, Warren Completion of Gibbard-Satterthwaite impossibility theorem; range voting and voter honesty.

- ↑ Balinski M. and R. Laraki (2007) «Election by Majority Judgement: Experimental Evidence». Cahier du Laboratoire d’Econométrie de l’Ecole Polytechnique 2007-28. Chapter in the book: «In Situ and Laboratory Experiments on Electoral Law Reform: French Presidential Elections», Edited by Bernard Dolez, Bernard Grofman and Annie Laurent. Springer, to appear in 2011.

- ↑ William Poundstone, Gaming the Vote, p238

- ↑ Balinski M. and R. Laraki (2007) «Election by Majority Judgement: Experimental Evidence». Cahier du Laboratoire d’Econométrie de l’Ecole Polytechnique 2007-28. Chapter in the book: «In Situ and Laboratory Experiments on Electoral Law Reform: French Presidential Elections», Edited by Bernard Dolez, Bernard Grofman and Annie Laurent. Springer, to appear in 2011.

- ↑ Schulze, Markus. "Free Riding and Vote Management under Proportional Representation by the Single Transferable Vote" (PDF).

- ↑ Woodall, Douglas R. (March 1994). "Computer counting in STV elections". McDougall Trust. Retrieved 6 March 2011.

Resources

- Cox, Gary (1997). Making Votes Count : Strategic Coordination in the World's Electoral Systems. Cambridge University Press. p. 340. ISBN 978-0-521-58527-9.

- Svensson, Lars-Gunnar (1999). The Proof of the Gibbard-Satterthwaite Theorem Revisited

- Brams, Herschbach (2001). "The Science of Elections, Science Online. Abstract

- Fisher, Stephen (2001). Extending the Rational Voter Theory of Tactical Voting

External links

- Tactical Voting Can Be a Weak Strategy—Article on tactical voting within larger strategic considerations [archived]

- VoteRoll.com VoteRoll is a blog roll voting system that offers tiered tactical voting to develop statistics for people voting online since 2010.

- VotePair.org VotePair is a banding together of the people who started tactical voting online in the 2000 US elections.