TRS-80 Color Computer

|

16k TRS-80 Color Computer 1 | |

| Developer | Tandy Corporation |

|---|---|

| Manufacturer | Motorola |

| Type | Home computer |

| Release date | 1980 |

| Introductory price | 399 USD$ (today $1145.92) |

| Discontinued | 1991 |

| Operating system | Color BASIC 1.0 / 2.0 / OS-9 |

| CPU | Motorola 6809E @ 0.895 MHz / 1.79 MHz |

| Memory | 4 kB / 16 kB / 32 kB / 64 kB / 128 kB / 512 kB |

| Graphics | MC6847 Video Display Generator (VDG) |

The Radio Shack TRS-80 Color Computer (also marketed as the Tandy Color Computer and affectionately nicknamed CoCo) is a line of home computers based on the Motorola 6809 processor. The Color Computer was launched in 1980, and lasted through three generations of hardware until being discontinued in 1991.

Summary

Despite bearing the TRS-80 name, the "Color Computer" is a radical departure from the earlier TRS-80; in particular it has a Motorola 6809E processor, rather than the TRS-80's Zilog Z80. Thus, despite the similar name, the new machine is not compatible with software made for the old TRS-80.[1]

The Motorola 6809E was an advanced processor for the time, but was correspondingly more expensive than other, more popular, microprocessors. Competing machines such as the Apple II, Commodore VIC-20, the Commodore 64, the Atari 400, and the Atari 800 were designed around the much cheaper MOS 6502. Some of these computers were paired with dedicated sound and graphics chips and were much more commercially successful in the 1980s home computer market.

The Tandy Color Computer line started in 1980 with what is now called the CoCo 1 and ended in 1991 with the more powerful, yet similar CoCo 3. All three CoCo models maintained a high level of software and hardware compatibility, with few programs written for the older model not running on the newer ones. The death knell of the CoCo was the advent of lower-cost IBM PC clones.

Origin and history

The TRS-80 Color Computer started out as a joint venture between Tandy Corporation of Fort Worth, Texas and Motorola Semiconductor, Inc. of Austin, to develop a low-cost home computer in 1977.

The initial goal of this project, called "Green Thumb," was to create a low cost Videotex terminal for farmers, ranchers, and others in the agricultural industry. This terminal would connect to a phone line and an ordinary color television and allow the user access to near-real-time information useful to their day-to-day operations on the farm.

Motorola's MC6847 Video Display Generator (VDG) chip was released about the same time as the joint venture started and it has been speculated that the VDG was actually designed for this project. At the core of the prototype "Green Thumb" terminal, the MC6847, along with the MC6809 microprocessor unit (MPU), made the prototype a reality by about 1978. Unfortunately, the prototype contained too many chips to be commercially viable. Motorola solved this problem by integrating all the functions of the many smaller chips into one chip, the MC6883 Synchronous Address Multiplexer (SAM). By that time in late 1979, the new and powerful Motorola MC6809 processor was released. The SAM, VDG, and 6809 were combined and the AgVision terminal was born.

The AgVision terminal was also sold through Radio Shack stores as the VideoTex terminal around 1980. Internal differences, if any, are unclear, as not many AgVision terminals survive to this day.

With its proven design, the VideoTex terminal contains all the basic components for a general-purpose home computer. The internal modem was removed, and I/O ports for cassette storage, serial I/O, and joysticks were provided. An expansion connector was added to the right side of the case for future enhancements and program cartridges ("Program Paks"), and a RAM button (a sticker indicating the amount of installed memory in the machine) covers the hole where the Modem's LED "DATA" indicator had been. On July 31, 1980, Tandy announced the TRS-80 Color Computer. Sharing the same case, keyboard, and layout as the AgVision/VideoTex terminals, at first glance it would be hard to tell the TRS-80 Color Computer from its predecessors.

The initial model (catalog number 26-3001) shipped with 4 kB of Dynamic Random Access Memory (DRAM) and an 8 kB Microsoft BASIC interpreter in ROM. Its price was 399 USD. Within a few months, Radio Shack stores across the US and Canada began receiving and selling the new computer.

Differences from earlier TRS-80 models

The Color Computer, with its Motorola 6809E processor, is very different from the Zilog Z80-based TRS-80 models; BYTE wrote that "The only similarity between [the two computers] is the name."[1] Indeed, the "80" in "TRS-80" stands for "Z80". For a time, the CoCo was referred to internally as the TRS-90 in reference to the "9" in "6809". However, this was dropped and all CoCos sold as Radio Shack computers were called TRS-80 in spite of the processor change.

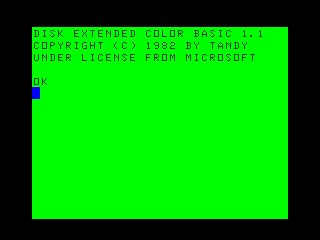

Like its Z80-based predecessors, the CoCo shipped with a version of BASIC. Tandy licensed Microsoft BASIC; as with the Z80 systems, there are multiple levels of BASIC. The original CoCo offered standard Color BASIC and Extended Color BASIC. This was further extended by a Disk Extended Color BASIC ROM included in the floppy controller. The CoCo 3 included Super Extended Color BASIC as standard, deploying extensions added by Microware. Third-party floppy controller ROMs, such as J&M System JDOS, and DSS Peripherals Disk Controller, enabled the use of double-sided disk drives.

The CoCo is designed to be attached to a color television set, whereas the Z80 machines use monochrome computer monitors, often built into the case. The CoCo also features an expansion connector for program cartridges (mostly games, although the EDTASM assembler is a cartridge) and other expansion devices, such as floppy-disk controllers and modems. In this way it is similar to the Atari 2600, Atari 8-bit computers, and other cartridge-capable systems. Tandy released a Multi-Pak Interface which allowed switching quickly among four cartridges. This is similar in concept to the Model I's Expansion Interface.

Unlike some Z80 models, the CoCo did not come with a built-in floppy drive. The CoCo is designed to save and load programs and data from a standard audio cassette deck. Tandy eventually offered a floppy disk drive controller for the CoCo as a cartridge. Both the CoCo and earlier TRS-80s share the WD17xx series floppy-disk controllers and 35- (later 40-) track industry-standard floppy drives. Floppy disk access would briefly halt the entire system while waiting for data.

Even with the add-on floppy drive, the CoCo did not have a true DOS until third-party operating systems such as TSC FLEX9 (distributed for the CoCo by Frank Hogg Laboratories) and Microware's multi-user, multi-tasking OS-9 were available. However, a disk-based CoCo does contain Disk Extended Color BASIC on an internal ROM in the controller cartridge that gives the BASIC user the ability to save and load programs from the disk and store and retrieve data from disk in various ways.

Some non-program expansion cartridges include a sound/voice synthesizer (which led to the CoCo being used as an accessibility device for the disabled[2]), 300-baud modem pack, an RS232 pack (the internal serial port was merely one bit of a parallel port), a hard-drive controller, stereo-music adapter, floppy-disk controller, input tablet, and other accessories. Some of this hardware was designed and marketed by third party mail-order houses, including a "Disto Super Controller" (a floppy controller, with space for an optional serial port or SCSI interface in the same enclosure). The CoCo was the first Tandy computer to have a mouse available for it; instead of following the IBM PC/Microsoft standard, this mouse was electrically the equivalent of an analogue joystick.

Versions

There were three versions of the Color Computer:

Color Computer 1 (1980–1983)

The original version of the Color Computer shipped in a large silver-gray case with a calculator-like "chiclet keyboard", and was available with memory sizes of 4K (26-3001), 16K (26-3002), or 32K (26-3003). Versions with at least 16K of memory installed shipped with standard Microsoft Color Basic or (optionally) Extended Color Basic. It used a regular TV for display, and TV-out was the only available connection to a display device.

The early versions of the CoCo 1 had a black keyboard surround, the TRS-80 nameplate above the keyboard to the left side, and a RAM badge ("button") affixed on the top and right side of the case. Later versions removed the black keyboard surround and RAM button, and moved the TRS-80 nameplate to the mid-line of the case.

The computer was based on a single printed-circuit board, with all semiconductors manufactured by Motorola including the MC6809E CPU, MC6847 VDG, MC6883 SAM, and RAM.[1] Initial versions of the CoCo were upgraded to 32K by means of piggybacking two banks of 16K memory chips and adding a few jumper wires. A later motherboard revision removed the 4K RAM option and were upgraded to 32K with "half-bad" 64K memory chips as a cost-cutting measure. These boards have jumpers marked HIGH/LOW to determine which half of the memory chip was good. This was transparent to the BASIC programmer since in either configuration 32K of memory was available. As memory production yields improved and costs went down, many (perhaps most) 32K CoCo 1s were shipped with perfectly good 64K memory chips; many utilities and programs began to take advantage of the "hidden" 32K.

Users opening the case risked invalidating the warranty.[1] Radio Shack could upgrade all versions that shipped with standard Color BASIC to Extended Color BASIC, developed by Microsoft, for $99. BYTE wrote in 1981 that through Extended Color BASIC, Radio Shack "has released the first truly easy-to-use and inexpensive system that generates full-color graphics".[3] Eventually the 32K memory option was dropped entirely and only 16K or 64K versions were offered.

In late 1982 a version of the Color Computer with a white case, called the TDP System 100, was distributed by RCA and sold through non-Tandy stores. Except for the nameplate and case, it was identical to the Color Computer.[4]

At some point after this, both the Coco and the TDP System 100 shipped with a white case which had ventilation slots that ran the entire length of the case, rather than only on the sides. This ventilation scheme was carried over to the CoCo 2. Some late versions of the CoCo also shipped with a modified keyboard, often referred to as the "melted" keyboard, which had bigger keycaps but a similar rubbery feel.

A number of peripherals were available: tape cassette storage, serial printers, a 5.25 inch floppy disk drive, a pen and graphics tablet called the "X-Pad", speech and sound generators, and joysticks.

|

Color Computer 2 (1983–1986)

During the initial CoCo 1 production run, much of the discrete support circuitry had been re-engineered into a handful of custom integrated circuits, leaving much of the circuit board area of the CoCo 1 as empty space. To cut production costs, the case was shortened by about 25% and a new, smaller power supply and motherboard were designed. The "melted" keyboard from the white CoCo 1 and the TDP-100 style ventilation slots were carried over. Aside from the new look and the deletion of the 12 volt power supply to the expansion connector, the computer was essentially 100% compatible with the previous generation. The deletion of the 12 volt power supply crippled some peripherals such as the original floppy disk controller, which then needed to be upgraded, installed in a Multi-Pak interface, or supplied with external power.

Production was also partially moved to Korea during the CoCo 2's life-span, and many owners of the Korean-built systems referred to them as "KoKos". Production in the USA and Korea happened in parallel using the same part numbers; very few, if any, differences exist between the USA built and Korean built CoCo 2 machines.

Upgraded BASIC ROMs were also produced, adding a few minor features and correcting some bugs. A redesigned 5-volt disk controller was introduced with its own new Disk BASIC ROM (v1.1). This controller added the "DOS" command which was used to boot the OS-9 operating system by Microware.

Later in the production run, the "melted" keyboard was replaced with a new, full-travel, typewriter-style keyboard.

The final significant change in the life of the CoCo 2 was made for the models 26-3134B, 26-3136B, and 26-3127B (16 kB standard, 16 kB extended, and 64 kB extended respectively). Internally this model was redesigned to use the enhanced VDG, the MC6847T1. This enhanced VDG allowed the use of lower case characters and the ability to change the text screen border color. For compatibility reasons neither of these features were used and were not enabled in BASIC, however the resourceful user could enable them by setting certain memory registers. Midway during the production run of these final CoCo 2s, the nameplate was changed from "Radio Shack TRS-80 Color Computer 2" to "Tandy Color Computer 2". The red, green, and blue shapes were replaced with red, green, and blue parallelograms.

|

Color Computer 3 (1986–1991)

On July 30, 1986, Tandy announced the Color Computer 3 at the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel in New York City. It came with 128 kB of RAM, which could be upgraded to 512 kB. The keyboard surround and cartridge door plastic were changed from black to grey. The keyboard layout was revised, putting the arrow keys in a diamond configuration and adding CTRL, ALT, F1 and F2 keys. It sold in Radio Shack stores and Tandy Computer Centers for $219.95 (199 CAD in Canada later that year). [5]

The CoCo 3 was compatible with most older software and CoCo 2 peripherals. Taking the place of the graphics and memory hardware in the CoCo 1 and 2 was an application-specific integrated circuit called the "GIME" (Graphics Interrupt Memory Enhancement) chip. The GIME also provided additional features:

- Output to a composite video monitor or analog RGB monitor, in addition to the CoCo 1 and 2's TV output. This did much to improve the clarity of its output.

- A paged memory management unit broke up the 6809's 64 kB address space into 8 × 8 kB chunks. Although these chunks were considered to be too large by many programmers, the scheme would later allow third party RAM upgrades of up to 2 MB (256 × 8 kB).

- Text display with real lowercase at 32, 40, 64, or 80 characters per line and between 16 and 24 lines per screen.

- Text character attributes, including 8 foreground and 8 background colors, underline, and blink.

- New graphics resolutions of 160, 256, 320 or 640 pixels wide by 192 to 225 lines.

- Up to 16 simultaneous colors from a palette of 64.

Omitted from the GIME were the seldom-used SAM-created Semigraphics 8, 12, and 24 modes. A rumored 256 color mode (detailed in the original Tandy spec for the GIME)[6] has never been found.

Previous versions of the CoCo ROM had been licensed from Microsoft, but by this time Microsoft was not interested in extending the code further. Instead, Microware provided extensions to Extended Color BASIC to support the new display modes. In order to not violate the spirit of the licensing agreement between Microsoft and Tandy, Microsoft's unmodified BASIC software was loaded in the CoCo 3's ROM. Upon startup, the ROM is copied to RAM and then patched by Microware's code. Although this was a clever way of adding features to BASIC, it was not without some flaws: the patched code had several bugs, and support for many of the new hardware features was incomplete.

Microware also provided a version of the OS-9 Level 2 operating system shortly after launch. This OS featured memory-mapping (so each process had its own memory space up to 64K), windowed display, and a more extensive development environment that included a bundled copy of BASIC09. C and Pascal compilers were available. Various members of the CoCo OS-9 community enhanced OS-9 Level 2 for the CoCo 3 at Tandy's request, but Tandy stopped production of the CoCo 3 before the upgrade was officially released. Most of the improvements made it into NitrOS-9, a major rewrite of OS-9/6809 Level 2 for the CoCo 3 to take advantage of the added features and speed of the Hitachi 6309 (if the unit has the Hitachi CPU installed).[7]

The 6809 in the CoCo 1 and 2 ran at 0.895 MHz; the CoCo 3 runs at that frequency by default, but is software controllable to run at twice that rate; OS-9 takes advantage of that capability.

A popular accessory was a high-resolution joystick adapter designed by CoCo enthusiast Steve Bjork. While it did increase the resolution of the joystick/mouse interface by a factor of ten, it did so at the expense of CPU time. A modified version of this interface was included with a software package by Colorware called CoCo-Max 3, by Dave Stamp. This was a MacPaint work-alike but added support for color graphics. This was a very desirable product for CoCo owners and combined with a MacWrite-like word processor called MAX-10 (also by Dave Stamp and internally named "MaxWrite"), provided some of the functionality of an Apple Macintosh, but with color graphics and at a fraction of the cost.

While the CoCo 3 featured many enhancements and was well received, it was not without problems and disappointments. As initially conceived, the CoCo 3 had much hardware acceleration and enhanced sound; these capabilities were scaled back due to aggressive cost-cutting and internal politics crippled the design so it would not be perceived as a threat to the Tandy 1000. This again limited the platform's potential as a game console. Early versions of the GIME had DRAM timing issues which caused random freezes. Due to bugs in the GIME some features that were problematic were marked as "reserved" or "do not use" in the programming and service manuals.

The power supply was marginal, and some would overheat if the system memory was expanded to the full 512 kB capacity due to the considerable heat generated by the additional RAM on the optional daughterboard. Some CoCo 3 owners opted to add a small fan inside the case to keep it cool.

Prototypes and rare versions

Various prototypes for the CoCo have surfaced over the years. In the 1980s, Radio Shack stores were selling a keyboard that would plug directly into a CoCo 2, though not labeled as such. This keyboard was part of a production run for the never produced Deluxe Color Computer. The Deluxe CoCo was referenced in CoCo manual sets and specifically mentioned as having extra keys, lowercase video, and the ability to accept commands in lowercase. Later versions of the CoCo 2, labeled Tandy instead of TRS-80, had the ability to display true lowercase, but did not accept lowercase commands, although this capability was later available through A-DOS, a third-party replacement ROM for the Disk Controller.

Production model CoCo 3s have been found with different circuit board layouts and socketed chips. In 2005, a rare CoCo 3 prototype surfaced at the Chicago CoCoFEST, with a built-in floppy disk drive controller and other items still not identified. It also did not use a GIME chip. Instead, all the functionality of the GIME was created using separate chips. There is a hobbyist effort to try to reverse engineer these chips so a modern GIME can finally be produced.

There is also a prototype Ethernet interface for the Color Computer, displaying a board layout date of 1984, and a few other mystery boards that have yet to be examined. There is some evidence that Tandy killed the Ethernet interface at the last minute: an ad mentioning the networking options for some of Tandy's Z80-based computers claimed that the Color Computer would soon have networking capabilities, and the printed manual for an upgraded version of OS-9 Level One listed networking in the table of contents, but had no corresponding text in the body of the manual.

CoCo clones and cousins

The Dragon 32 and 64 computers were British cousins of the CoCo based on a reference design from Motorola that was produced as an exemplar of the capabilities of the MC6809E (MPU) when coupled with the MC6847 (Video Display Generator - VDG) and the MC6883 (Synchronous Address Multiplexer - SAM). The BIOS code for the Dragon 32 was rewritten based on specifications and API drawn up by Microsoft and, to a certain extent, PA Consulting of Cambridge. The Dragon was a much improved unit with video output in addition to the TV output of the CoCo and CoCo 2. It also featured a Centronics parallel port (not present on any CoCo), an integrated 6551A serial UART (on the Dragon 64), and a higher-quality keyboard. In 1983, a version of the Dragon was licensed for manufacture for the North American market by Tano Corporation of New Orleans, Louisiana. Tano started production at their 48,000-square-foot (4,500 m2) facility in September 83 and were running at capacity just one month later. Unfortunately sales weren't as good as expected and Tano stopped production and support just one year later.[8] A California surplus equipment company, California Digital, bought the remaining stock of Tano built Dragon 64 shortly after and has had new in-the-box Dragon 64s available for purchase as of December 2009.[9]

In Brazil, there existed several CoCo-clones, including the Prologica CP400 Color and CP400 Color II, the Varixx VC50, the LZ Color64, the Dynacom MX1600, the Codimex CD6809, and the "vaporware" Microdigital TKS800.

In Mexico, the Micro-SEP, a CoCo 2 clone with 64 kB of memory, was introduced by the Secretary of Education. The Micro-SEP was intended to be distributed nationally to all the public schools teaching the 7th to 9th grades. They were presented as a design of the Center of Advanced Research and Studies (CINVESTAV) of the National Polytechnic Institute (IPN).[10] Like the Dragon, these computers also included video output. Whether these computers were "designed" by this institute, or were licensed from the original design, is unclear.

A Taiwan-based company, Sampo, also made a CoCo clone, the Sampo Color Computer.[11] The Sampo was supposedly available in Taiwan, Korea, and possibly other Asian countries. It is believed that Tandy blocked sales in the US with legal action due to copyright infringements on the ROM code.

A cousin of the CoCo, the MC-10, or Micro Color Computer, was sold in Radio Shack stores as an entry-level computer at a lower cost than the CoCo. Released in 1983, it was similar in appearance to the Timex Sinclair models. Like the CoCo, it used the MC6847 VDG and Microsoft Basic, but featured the MC6803 instead of the 6809. The MC-10 lacked such features as an 80 column printer and disk storage system, as well as a "real" keyboard. Accordingly, it did not sell well and was withdrawn after just two years of production.[12] An MC-10 clone, the Sysdata Tcolor, was available in Brazil with 16 kB ROM.

Hardware design and integrated circuits

Internally the CoCo 1 and CoCo 2 models are functionally identical. The core of the system is virtually identical to the reference design included in the Motorola MC6883 data sheet and consists of five LSI chips:

- MC6809E Microprocessor Unit (MPU)

- MC6883/SN74LS783/SN74LS785 Synchronous Address Multiplexor (SAM)

- MC6847 Video Display Generator (VDG)

- Two Peripheral Interface Adapters (PIA), either MC6821 or MC6822 chips

SAM

The SAM is a multifunction device that performs the following functions:

- Clock generation and synchronization for the 6809E MPU and 6847 VDG

- Up to 64K Dynamic Random Access Memory (DRAM) control and refresh

- Device selection based on MPU memory address to determine if the MPU access is to DRAM, ROM, PIA, etc.

- Duplication of the VDG address counter to "feed" the VDG the data it is expecting

The SAM was designed to replace numerous small LS/TTL chips into one integrated package. Its main purpose is to control the DRAM but, as outlined above, it integrates several other functions as well. It is connected to a crystal at 4 times the television colorburst frequency (14.31818 MHz for NTSC countries). This is divided by 4 internally and is fed to the VDG for its own internal timing (3.579545 MHz for NTSC). The SAM also divides the master clock by 16 (or 8 in certain cases) for the two phase MPU clock; in NTSC this is .89 MHz (or 1.8 MHz if divided by 8).

Switching the SAM into 1.8 MHz operation gives the CPU the time ordinarily used by the VDG and refresh. As such, the display shows garbage; this mode was seldom used. However, an unusual mode available by the SAM is called the Address Dependent mode, where ROM reads (since they do not use the DRAM) occur at 1.8 MHz but regular RAM access occurs at .89 MHz. In effect, since the BASIC interpreter runs from ROM, putting the machine in this mode would nearly double the performance of a BASIC program while maintaining video display and DRAM refresh. Of course, this would throw off the software timing loops and I/O operations would be affected. Despite this, however, the "high speed POKE" was used by many CoCo BASIC programs even though it overclocked the hardware in the CoCo, which was only rated for 1 MHz operation.

The SAM has no connection to the MPU data bus. As such, it is programmed in a curious manner; its 16-bit configuration register is spread across 32 memory addresses (FFC0-FFDF). Writing even bytes sets that register bit to 0, Writing to odd bytes sets it to 1.

Due to limitations in 40-pin packaging, the SAM contains a duplicate of the VDG's internal 12-bit address counter. Normally this counter's settings are set to duplicate the VDG's display mode. However, this is not required and results in the creation of some new display modes not possible when the VDG is used in a system alone. Instead of the VDG requesting data from RAM by itself, the VDG is "fed" data by the SAM's internal copy of the VDG address counter. This process is called "Interleaved Direct Memory Access" (IDMA) by Motorola and ensures that the processor and VDG always have full access to this shared memory resource with no wait states or contention.

There are two versions of the SAM. The early one is labeled MC6883 and/or SN74LS783; the later version is labeled SN74LS785. There are some minor timing differences, but the major difference is the support of an 8-bit refresh counter in the 785 version. This allowed for use of inexpensive 16K by 4-bit and certain 64K by 1-bit DRAMs. Some third party bank-switching memory upgrades that used 256K DRAMs needed this 8-bit refresh counter to work.

VDG

The MC6847 is display generator capable of displaying text and graphics contained within a roughly square display matrix 256 pixels wide by 192 lines high. It can display 9 colors: black, green, yellow, blue, red, buff (almost-but-not-quite white), cyan, magenta, and orange.

Alphanumeric/Semigraphics display

The CoCo is physically wired such that its default alphanumeric display is actually "Semigraphics 4" mode.

In alphanumeric mode, each character is a 5 dot wide by 7 dot high character in a box 8 dots wide and 12 lines high. This display mode consumes 512 bytes of memory and is a 32 character wide screen with 16 lines. The internal ROM character generator only holds 64 characters, so no lower case characters are provided. Lower case characters were rendered as upper case characters with inverted color. Although simulated screen shots would show this as green on black, on most CoCo generations it was actually green on very dark green.

Semigraphics is a hybrid display mode where alphanumerics and chunky block graphics can be mixed together on the same screen. If the 8th bit of the character is set, it is a semigraphics character. If cleared, it is an alphanumeric. When the 8th bit is set, the next three bits determine the color and last 4 bits determine which "quadrant" of the character box is either the selected color or black. This is the only mode where it is possible (without sneaky tricks) to display all 9 colors on the screen simultaneously. If used to only display semigraphics, the screen becomes a 64×32 nine color graphics mode. The CoCo features several BASIC commands to manage this screen as a low-res graphics display.

The alphanumeric display has two colorsets. The one used by default on the CoCo has black characters on a green background. The alternate has black characters on an orange background. The colorset selection does not affect semigraphics characters. The border in this mode is always black.

The 6847 is capable of a Semigraphics 6 display mode, where two bits select a color and 6 bits determine which 1/6 of the character box is lit. In this mode only 4 colors are possible but the Colorset bit of the VDG can select two different groups of the 4 colors. Due to a peculiarity of its hardware, only two colors are available in graphics blocks when using Semigraphics 6 on the CoCo.[13]

Additional Semigraphics modes

By setting the SAM such that it believes it is displaying a full graphics mode, but leaving the VDG in Alphanumeric/Semigraphics 4 mode, it is possible to subdivide the character box into smaller pieces. This creates the "virtual" modes Semigraphics 8, 12, and 24.[14] In these modes it was possible to mix bits and pieces of different text characters as well as Semigraphics 4 characters. These modes were an interesting curiosity but not widely used, as the Semigraphics 24-screen consumed 6144 bytes of memory. These modes were not implemented on the CoCo 3.

A programmer's reference manual for the CoCo states that due to a fire at Tandy's research lab, the papers relating to the semigraphics modes were shuffled, and so some of the semigraphics modes were never documented. CoCo enthusiasts created experimental programs to try to reverse engineer the modes, and were able to reconstruct the missing documentation.[15]

Graphics display

There were several full graphics display modes, which were divided into two categories: "resolution" graphics and "color" graphics. In resolution modes, each pixel is addressable as either on or off. There are two colorsets available, the first was black dots on a green background and green border, the second, more commonly used one has white dots on a black background with a white border. In color modes, each pixel was two bits, selecting one of four colors. Again the colorset input to the VDG determined which colors were used. The first colorset has a green border, and the colors green, yellow, red, and blue were available. The second colorset has a white border and the colors white, cyan, magenta and orange were available. Resolution graphics have 8 pixels per byte and are available in 128×64, 128×96, 128×192, and 256×192 densities. Color graphics have 4 pixels per byte and are available in 64×64, 128×64, 128×96, and 128×192 densities. The maximum size of a graphics screen is 6144 bytes.

Artifact colors

The 256×192 two color graphics mode uses four colors due to a quirk in the NTSC television system (see composite artifact colors). It is not possible to reliably display 256 dots across the screen due to the limitations of the NTSC signal and the phase relationship between the VDG clock and colorburst frequency.

In the first colorset, where green and black dots are available, alternating columns of green and black are not distinct and appear as a muddy green color. However, when one switches to the white and black colorset, instead of a muddy gray as expected, the result is either orange or blue. Reversing the order of the alternating dots will give the opposite color. In effect this mode becomes a 128×192 4 color graphics mode where black, orange, blue, and white are available (the Apple II created color graphics by exploiting a similar effect).

Most CoCo games used this mode as the colors available are more useful than the ones provided in the hardware 4 color modes. Unfortunately the VDG internally can power up on either the rising or falling edge of the clock, so the bit patterns that represent orange and blue are not predictable. Most CoCo games would start up with a title screen and invited the user to press the reset button until the colors were correct. The CoCo 3 fixed the clock-edge problem so it was always the same; a user would hold the F1 key during reset to choose the other color set.

On a CoCo 3 with an analog RGB monitor, the black and white dot patterns do not artifact; to see them one would have to use a TV or composite monitor, or patch the games to use the hardware 128×192 four color mode in which the GIME chip allows the color choices to be mapped. Users in PAL countries saw green and purple stripes instead of solid red and blue colors.

Readers of The Rainbow or Hot CoCo magazine learned that they could use some POKE commands to switch the 6847 VDG into one of the artifact modes, while Extended Color Basic continued to operate as though it were still displaying one of the 128×192 four-color modes. Thus, the entire set of Extended Color Basic graphics commands could be used with the artifact colors. Some users went on to develop a set of 16 artifact colors using a 4×2 pixel matrix, giving this set of colors: black, dark cyan, brick red, light violet, dark blue, azure (the blue above), olive green, brown, purple, light blue, orange, yellow, light gray, blue-white, pink-white, and white. Use of POKE commands also made these colors available to the graphics commands, although the colors had to be drawn one horizontal line at a time. Some interesting artworks were produced from these effects, especially since the CoCo Max art package provided them in its palette of colors.

Lower case and the 6847T1

The 6847 is capable of using an external character generator. Several third party add-on adapter boards would allow the CoCo to display real lowercase characters.

Very late in the CoCo 2 production run, an enhanced VDG was available. Called the 6847T1, it included a lower case character generator and the ability to display a green/orange or black border on the text screen. Its other changes were mainly to reduce parts count by incorporating an internal data latch. The lower case capability of this VDG is not enabled by default on this system and is not even mentioned in the manual. Only through some tinkering and research was this feature discovered by intrepid CoCo users.

The 6847T1 may also carry the part number XC80652P; these may have been pre-release parts.

PIAs

There are two PIA chips in all CoCo models. The PIAs are dedicated mainly to I/O operations such as driving the internal 6-bit Digital-to-analog converter (DAC), reading the status of the DAC's voltage comparator, controlling the relay for the cassette motor, reading the keyboard matrix, controlling the VDG mode control pins, reading and writing to the RS232 serial I/O port, and controlling the internal analog multiplexers.

The earliest CoCo models had two standard 6821 chips. Later, due to changes in the keyboard design, it was found that the 6822 IIA (industrial interface adapter) was better suited to the keyboard's impedance. The 6822 was eventually discontinued by Motorola but was produced for Tandy as an ASIC with a special Tandy part number, SC67331P. Functionally the 6821 and 6822 are identical and one can put a 6821 in place of the 6822 if that part is bad. Some external pull-up resistors may be needed to use a 6821 to replace a 6822 in a CoCo for normal keyboard operation.

Interface to external peripherals

Due to the CoCo's design, the MPU encounters no wait states in normal operation. This means that precise software controlled timing loops are easily implemented. This is important, since the CoCo has no specialized hardware for any I/O. All I/O operations, such as cassette reading and writing, serial I/O, scanning the keyboard, and reading the position of the joysticks, must be done entirely in software. This reduces hardware cost, but reduces system performance as the MPU is unavailable during these operations.

As an example, the CoCo cassette interface is perhaps one of the fastest available (1500-bit/s) but it does so entirely under software control. While reading or writing a cassette the CoCo has no CPU time free for other tasks. They must wait until an error occurs or all the data needed is read.

CoCo 3 hardware changes

The hardware in the CoCo 1 and CoCo 2 models was functionally the same; the only differences were in packaging and integration of some functions into small ASICs. The CoCo 3 radically changed this. A new VLSI ASIC, called (officially) the Advanced Color Video Chip (ACVC) or (unofficially) the Graphics Interrupt Memory Enhancer (GIME), integrated the functions of the SAM and VDG while enhancing the capabilities of both. Aside from the graphics enhancements outlined above, the CoCo 3 offered true lower case, 40 and 80 column text display capability, and the ability to run at 1.8 MHz without loss of video display. As such the processor was changed to the 68B09E and the PIA was changed to the 68B21, which are 2 MHz rated parts.

Competition

The CoCo's main competition was from the Commodore VIC-20, Commodore 64, Apple II, and the Atari 400 and Atari 800.

While the CoCo sported perhaps the most advanced 8-bit processor ever made, that processing power came at a significant price premium. In order to sell the CoCo at a competitive price, its relatively expensive processor was not tied to any specialized video or sound hardware. In comparison, the 6502-derived processor in the Commodore, Apple and Atari systems was much less expensive. Both Commodore and Atari had invested in advanced graphics and sound chip design for arcade games and home gaming consoles. By tying these specialized circuits with an inexpensive processor, Atari and Commodore systems were able to play sophisticated games with high quality graphics and sound. The trade-off is between a system with an expensive CPU that does a lot of work, or an inexpensive CPU that controls the registers of its sound and video hardware.

The CoCo video hardware was derived from a chip designed as display for a character based terminal, and is a completely "dumb" device. Similarly, the sound hardware is little more than a 6-bit DAC under software control. All graphics and sound require direct CPU intervention, and while this allows for great flexibility, its performance is much lower than dedicated hardware.

Games drove system sales then as they do now, and with its poor gaming performance, the CoCo attracted little interest in officially licensed ports of popular games. The CoCo 3 did improve graphics capability and doubled CPU performance, but still contained no hardware graphics or sound acceleration. Drawing was performed by the CPU, and most of the new graphics modes required at least twice as much processor time due to increased display resolution and color depth. The sound hardware was not changed at all.

Every computer platform is a compromise, and despite the significant graphics and sound handicap the CoCo may have had, it still had a sophisticated CPU under its hood with extremely high performance. There were many independent clones of popular games available, but far more important was the availability of "killer apps" for the CoCo. For instance, CoCo-Max and Max-10 were clones of MacPaint and MacWrite. The OS-9 operating system, a UNIX-like multi-tasking multi-user environment, was also available. Even the BASIC interpreter was one of the most powerful available, and provided the user with a rich set of easy-to-use commands for manipulating on-screen graphics and playing sounds.

Some of the hardware limitations were overcome with external add-ons, particularly expansion cartridges. Some were made by Tandy, some by other manufacturers. Examples are:

- RS232 Program Pak, which provided a real RS232 UART for serial communications (the 6551A)

- The Speech & Sound Pak, which provided a speech synthesizer and a sound generator chip

- Word-Pak and Word-Pak II 80 column display adapters produced by PBJ, Inc. allowed connection to an external monochrome monitor (not needed for CoCo 3).

- 300 baud modem pak

- Advanced floppy and hard drive controllers (mostly for OS-9)

Key to taking advantage of these expansion capabilities is the Multi-Pak interface, which permits up to four devices such as these to be attached to the system at the same time.

The OS-9 divide

There is a major division of CoCo users: those who used the OS-9 operating system and those who used Disk Extended Color BASIC (DECB). The divide comes from the fact that programs using DECB (except for those that used CoCo's form of BASIC) used DECB only as a loader and for disk I/O, communicating with the hardware directly for all other activities. OS-9 applications communicate with OS-9 and its drivers. This allows for a degree of hardware independence.

Many programs written for the CoCo were DECB programs. In order to support such programs (or at least, those that bypassed BASIC and addressed hardware directly), any future CoCo version would have to be hardware-compatible with the CoCo, or perfectly emulate every aspect of the CoCo. In contrast, OS-9 programs relied only on OS-9 functions, and its drivers could be rewritten to work with different hardware. However, DECB came with the CoCo system itself, and required no further setup or purchasing. OS-9 was an additional product that had to be loaded manually each time the computer was started. Writing an OS-9 program meant appealing to a smaller subset of the CoCo community; this discouraged development of OS-9 products.

The end of the road

On October 26, 1990, Ed Juge of Tandy announced that the CoCo 3 would be dropped from its computer line. With no apparent successor mentioned, the announcement was disheartening to many loyal CoCo fans.

Even today, current and former CoCo owners agree that Tandy did not take the CoCo very seriously, despite it having been their best-selling computer for several years. Tandy failed to market the CoCo as the powerful and useful machine that it was, and offered customers no hint about the large number of third party software and hardware products available for it.

The release of the CoCo 3 was particularly lackluster despite its greatly enhanced graphic capabilities and RGB monitor support. Radio Shack fliers and stores typically depicted the CoCo 3 running CoCo 2 games, and offered a very limited selection of CoCo 3 specific software. There was an official Radio Shack store demo,[16] but few stores bothered to run it. In addition, Tandy released the CoCo 3 well after the release of the Amiga, and the weaker hardware meant the bouncing ball demo was unflattering in comparison to the Amiga's.

Additionally, DRAM prices skyrocketed at the time the CoCo 3 was released, making the 512 kB memory upgrade considerably more expensive than the 128K CoCo 3 itself. Very few stores displayed a 512K machine or a CoCo 3 running such games as King's Quest III or Leisure Suit Larry.

Successors

In spite of Tandy's apparent lack of concern for the CoCo market, there were rumors of the existence of a prototype CoCo 4 at Tandy's Fort Worth headquarters. Several first hand accounts of the prototype came from people like Mark Siegel of Tandy and Ken Kaplan of Microware, yet there exists no known physical evidence of such a machine.

A few independent companies attempted to carry the CoCo torch, but the lack of decent backwards compatibility with the CoCo 3 failed to entice much of the CoCo community over to these new independent platforms. Many of these independent platforms did run OS9/68k, which was very similar to OS-9. However the bulk of the CoCo community moved on to more mainstream platforms. Some CoCo users swore their loyalty to Motorola and moved on to the Amiga, Atari ST, and the Macintosh, all of which were based on the Motorola 68000 processor. Others jumped to the IBM PC-compatible.

Tomcat

Frank Hogg Labs introduced the Tomcat TC-9 in June 1990, which was somewhat compatible with the CoCo 3, but was mostly only able to run OS-9 software. A later version called the TC-70 (running on a Signetics 68070) had strong compatibility with the MM/1, and also ran OS-9/68K.

MM/1

The Multi-Media One was introduced in July 1990, ran OS-9/68K on a 15 MHz Signetics 68070 processor with 3 MB RAM, and had a 640×208 graphics resolution as well as supporting a 640×416 interlaced mode. It included a SCSI interface, stereo A/D and D/A conversion, an optional MIDI interface, and (later) an optional board to upgrade the CPU to a Motorola 68340 running at up to 25 MHz. It is estimated that about 500 units were sold.

AT306

The AT306 (also known as the MM/1B) was a successor to the MM/1 that contained a Motorola 68306 CPU, OS-9/68K 3.0, and was designed to allow the use of ISA bus cards. It was created by Kevin Pease and Carl Kreider, and sold by Carl's company, Kreider Electronics. It was also sold as the "WCP-306" by Bill Wittman of Wittman Computer Products.

Delmar System IV/Peripheral Technology PT68K-4

Peripheral Technology produced a 16 MHz Motorola 68000 system called a PTK68K-4, which was sold as a kit or a complete motherboard. Delmar sold complete systems based on the PT68K-4 and called the Delmar System IV. The PT68K-4 has the footprint of an IBM PC, so it will fit in a normal PC case, and it has seven 8-bit ISA slots. Video was provided by a standard IBM style monochrome, CGA, EGA, or VGA video card and monitor, but for high resolution graphics the software only supported certain ET4000 video cards. It appears that most users of this system used/uses OS-9, but there are several operating systems for it, including REX (a FLEX-like OS), and SK*DOS. Dan Farnsworth, who wrote REX, also wrote a BASIC interpreter that was fairly compatible to DECB, but it was too little, too late to be of interest to many CoCo users. There was also a card available called an ALT86, which was basically an IBM XT compatible computer on a card, which allowed the user to run DOS programs on it. In fact, both the 68000 and the ALT86 card could be run at the same time, if access to the ISA bus was not needed from the 68000 side of it.

The 21st century

The CoCo still has a small but active user community despite a perceived lack of support from Tandy. Third-party support was assisted by CoCo-related periodicals, notably The Rainbow, Hot CoCo, and The Color Computer Magazine. Original hardware is being expanded by some small firms such as Cloud-9 with such things as SCSI and IDE hard drive controllers, memory upgrades to 512K and PS/2 Keyboard interfaces. Other recent hardware development includes an RGB-to-VGA Converter that allows connecting a CoCo 3 to a standard VGA compatible monitor.

User-driven support for the Color Computer has continued, hosted on various web sites and forums.

Emulation

Emulation of the CoCo hardware has been possible on x86 PCs since at least the mid '90s. MESS is capable of emulating the CoCo. Other emulators include VCC, Jeff Vavasour's CoCo emulators and Mocha, a web-based emulator written in JavaScript that can emulate a CoCo 2 inside a web browser.

Most of these emulators require a dump from the CoCo ROMs. Instructions are usually provided with the emulators on how to get a ROM dump from a CoCo. A ROM might be found online, which may be from a Brazilian CoCo clone.

Utilities exist to transfer data from a PC to a CoCo. If one does not have compatible disk drives for the PC and CoCo, data may still be transferred by using special PC CoCo utilities to create a .wav audio file of the data. Hook the CoCo's cassette interface cables directly to the line out of a PC's soundcard, initiate the CLOAD (or CLOADM) command on the CoCo, and then play the sound file from the PC.

See also

- Category:TRS-80 Color Computer games

- Dungeons of Daggorath

- To Preserve Quandic

References

- 1 2 3 4 Ahrens, Tim; Browne, Jack; Scales, Hunter (1981-03-00). "What's Inside Radio Shack's Color Computer?". BYTE. p. 90. Retrieved 14 June 2014. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Vassilopoulous, Charles A. (1985-12-00). "Speaking Up for the Handicapped". Hot CoCo. p. 51. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Miastkowski, Stan (May 1981). "Extended Color BASIC for the TRS-80 Color Computer". BYTE. p. 37. Retrieved 18 October 2013.

- ↑ "Pipeline". The Rainbow. September 1982. p. 56. Retrieved 17 October 2013.

- ↑ Sims, Calvin (31 July 1986). "5 Models Introduced By Tandy". The New York Times (The New York Times). Retrieved 19 October 2015.

- ↑ Nickolas Marentes. "In Search of 256". Retrieved 2008-06-11.

- ↑ "NitrOS-9 operating system for the Tandy/Radio Shack Color Computer". Retrieved 2008-06-11.

- ↑ Dragon Archive History <http://archive.worldofdragon.org/index.php?title=Dragon_History>

- ↑ http://www.cadigital.com/computer.htm

- ↑ "Red Escolar y el modelo de uso de las Tecnologías de la Información y la Comunicación en Educación". 4º Encuentro Nacional de Red Escolar (in Spanish). October 16, 2006. Retrieved 2008-06-11.

- ↑ Nov. 1982 BYTE Magazine ad

- ↑ 1984 Tandy Catalog RSC 11 was the last to have the MC-10 <http://www.radioshackcatalogs.com/extra_stuff.html>

- ↑ http://www.cs.unc.edu/~yakowenk/coco/text/semigraphics.html

- ↑ Chris Lomont's Color Computer 1/2/3 Hardware Programming

- ↑ The Forgotten Graphics Mode

- ↑ L. Curtis Boyle (April 19, 2006). "Official Radio Shack Coco 3 Demo". NitrOS9.LCURTISBOYLE.COM. Retrieved 2008-06-11.

External links

- CoCo: The Colorful History of Tandy’s Underdog Computer

- CoCo Chronicles, a history of the Color Computer

- CoCopedia, the TRS-80 CoCo Wiki

- The Tandy Color Computer Resource Site

- Color computer technical reference or Color computer technical reference.pdf

- Mocha - The JavaScript Color Computer Emulator

- Dragon/CoCo emulator written in Python on GitHub

- Color Computer/OS-9 Forum at Delphiforums (formerly Delphi). Forum was originally operated by Falsoft, publisher of Rainbow magazine.

- Micro Colour Computer MC-10 Service Manual

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to TRS-80 Color Computer. |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

_4x3.jpg)