Nuclear fuel

Nuclear fuel is a material that can be 'burned' by nuclear fission or fusion to derive nuclear energy. Nuclear fuel can refer to the fuel itself, or to physical objects (for example bundles composed of fuel rods) composed of the fuel material, mixed with structural, neutron-moderating, or neutron-reflecting materials.

Most nuclear fuels contain heavy fissile elements that are capable of nuclear fission. When these fuels are struck by neutrons, they are in turn capable of emitting neutrons when they break apart. This makes possible a self-sustaining chain reaction that releases energy with a controlled rate in a nuclear reactor or with a very rapid uncontrolled rate in a nuclear weapon.

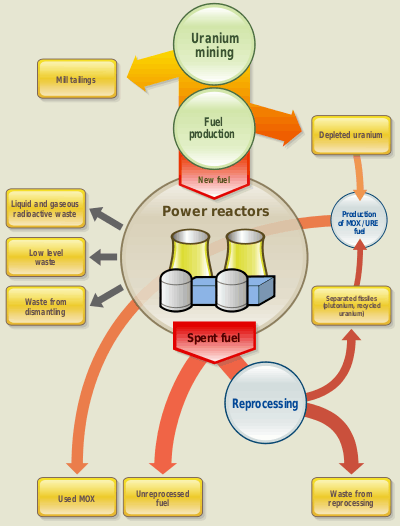

The most common fissile nuclear fuels are uranium-235 (235U) and plutonium-239 (239Pu). The actions of mining, refining, purifying, using, and ultimately disposing of nuclear fuel together make up the nuclear fuel cycle.

Not all types of nuclear fuels create power from nuclear fission. Plutonium-238 and some other elements are used to produce small amounts of nuclear power by radioactive decay in radioisotope thermoelectric generators and other types of atomic batteries. Also, light nuclides such as tritium (3H) can be used as fuel for nuclear fusion.

Nuclear fuel has the highest energy density of all practical fuel sources.

Oxide fuel

For fission reactors, the fuel (typically based on uranium) is usually based on the metal oxide; the oxides are used rather than the metals themselves because the oxide melting point is much higher than that of the metal and because it cannot burn, being already in the oxidized state.

UOX

Uranium dioxide is a black semiconducting solid. It can be made by reacting uranyl nitrate with a base (ammonia) to form a solid (ammonium uranate). It is heated (calcined) to form U3O8 that can then be converted by heating in an argon / hydrogen mixture (700 °C) to form UO2. The UO2 is then mixed with an organic binder and pressed into pellets, these pellets are then fired at a much higher temperature (in H2/Ar) to sinter the solid. The aim is to form a dense solid which has few pores.

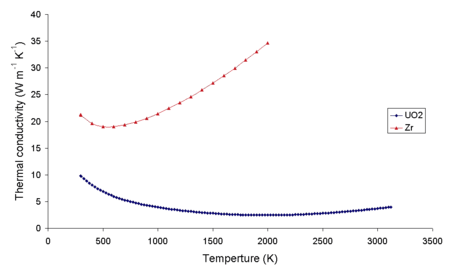

The thermal conductivity of uranium dioxide is very low compared with that of zirconium metal, and it goes down as the temperature goes up.

It is important to note that the corrosion of uranium dioxide in an aqueous environment is controlled by similar electrochemical processes to the galvanic corrosion of a metal surface.

MOX

Mixed oxide, or MOX fuel, is a blend of plutonium and natural or depleted uranium which behaves similarly (though not identically) to the enriched uranium feed for which most nuclear reactors were designed. MOX fuel is an alternative to low enriched uranium (LEU) fuel used in the light water reactors which predominate nuclear power generation.

Some concern has been expressed that used MOX cores will introduce new disposal challenges, though MOX is itself a means to dispose of surplus plutonium by transmutation.

Reprocessing of commercial nuclear fuel to make MOX was done in the Sellafield MOX Plant (England). As of 2015, MOX fuel is made in France (see Marcoule Nuclear Site), and to a lesser extent in Russia (see Mining and Chemical Combine), India and Japan. China plans to develop fast breeder reactors (see CEFR) and reprocessing.

The Global Nuclear Energy Partnership, is a U.S. plan to form an international partnership to see spent nuclear fuel reprocessed in a way that renders the plutonium in it usable for nuclear fuel but not for nuclear weapons. Reprocessing of spent commercial-reactor nuclear fuel has not been permitted in the United States due to nonproliferation considerations. All of the other reprocessing nations have long had nuclear weapons from military-focused "research"-reactor fuels except for Japan.

Metal fuel

Metal fuels have the advantage of a much higher heat conductivity than oxide fuels but cannot survive equally high temperatures. Metal fuels have a long history of use, stretching from the Clementine reactor in 1946 to many test and research reactors. Metal fuels have the potential for the highest fissile atom density. Metal fuels are normally alloyed, but some metal fuels have been made with pure uranium metal. Uranium alloys that have been used include uranium aluminum, uranium zirconium, uranium silicon, uranium molybdenum, and uranium zirconium hydride. Any of the aforementioned fuels can be made with plutonium and other actinides as part of a closed nuclear fuel cycle. Metal fuels have been used in water reactors and liquid metal fast breeder reactors, such as EBR-II.

TRIGA fuel

TRIGA fuel is used in TRIGA (Training, Research, Isotopes, General Atomics) reactors. The TRIGA reactor uses UZrH fuel, which has a prompt negative fuel temperature coefficient of reactivity, meaning that as the temperature of the core increases, the reactivity decreases—so it is highly unlikely for a meltdown to occur. Most cores that use this fuel are "high leakage" cores where the excess leaked neutrons can be utilized for research. TRIGA fuel was originally designed to use highly enriched uranium, however in 1978 the U.S. Department of Energy launched its Reduced Enrichment for Research Test Reactors program, which promoted reactor conversion to low-enriched uranium fuel. A total of 35 TRIGA reactors have been installed at locations across the USA. A further 35 reactors have been installed in other countries.

Actinide fuel

In a fast neutron reactor, the minor actinides produced by neutron capture of uranium and plutonium can be used as fuel. Metal actinide fuel is typically an alloy of zirconium, uranium, plutonium, and minor actinides. It can be made inherently safe as thermal expansion of the metal alloy will increase neutron leakage.

Molten plutonium

Molten plutonium, alloyed with other metals to lower its melting point and encapsulated in tantalum,[1] was tested in two experimental reactors, LAMPRE I and LAMPRE II, at LANL in the 1960s. "LAMPRE experienced three separate fuel failures during operation."[2]

Ceramic fuels

Ceramic fuels other than oxides have the advantage of high heat conductivities and melting points, but they are more prone to swelling than oxide fuels and are not understood as well.

Uranium nitride

This is often the fuel of choice for reactor designs that NASA produces, one advantage is that UN has a better thermal conductivity than UO2. Uranium nitride has a very high melting point. This fuel has the disadvantage that unless 15N was used (in place of the more common 14N) that a large amount of 14C would be generated from the nitrogen by the (n,p) reaction. As the nitrogen required for such a fuel would be so expensive it is likely that the fuel would have to be reprocessed by pyroprocessing to enable the 15N to be recovered. It is likely that if the fuel was processed and dissolved in nitric acid that the nitrogen enriched with 15N would be diluted with the common 14N.

Uranium carbide

Much of what is known about uranium carbide is in the form of pin-type fuel elements for liquid metal fast reactors during their intense study during the 1960s and 1970s. However, recently there has been a revived interest in uranium carbide in the form of plate fuel and most notably, micro fuel particles (such as TRISO particles).

The high thermal conductivity and high melting point makes uranium carbide an attractive fuel. In addition, because of the absence of oxygen in this fuel (during the course of irradiation, excess gas pressure can build from the formation of O2 or other gases) as well as the ability to complement a ceramic coating (a ceramic-ceramic interface has structural and chemical advantages), uranium carbide could be the ideal fuel candidate for certain Generation IV reactors such as the gas-cooled fast reactor.

Liquid fuels

Liquid fuels are liquids containing dissolved nuclear fuel and have been shown to offer numerous operational advantages compared to traditional solid fuel approaches.

Liquid-fuel reactors offer significant safety advantages due to their inherently stable "self-adjusting" reactor dynamics. This provides two major benefits: - virtually eliminating the possibility of a run-away reactor meltdown, - providing an automatic load-following capability which is well suited to electricity generation and high temperature industrial heat applications.

Another major advantage of the liquid core is its ability to be drained rapidly into a passively safe dump-tank. This advantage was conclusively demonstrated repeatedly as part of a weekly shutdown procedure during the highly successful 4 year ORNL MSRE program.

Another huge advantage of the liquid core is its ability to release xenon gas which normally acts as a neutron absorber and causes structural occlusions in solid fuel elements (leading to early replacement of solid fuel rods with over 98% of the nuclear fuel unburned, including many long lived actinides). In contrast Molten Salt Reactors (MSR) are capable of retaining the fuel mixture for significantly extended periods, which not only increases fuel efficiency dramatically, but also incinerates the vast majority of its own waste as part of the normal operational characteristics.

Molten salts

Molten salt fuels have nuclear fuel dissolved directly in the molten salt coolant. Molten salt-fueled reactors, such as the liquid fluoride thorium reactor (LFTR), are different from molten salt-cooled reactors that do not dissolve nuclear fuel in the coolant.

Molten salt fuels were used in the LFTR known as the Molten Salt Reactor Experiment, as well as other liquid core reactor experiments. The liquid fuel for the molten salt reactor was a mixture of lithium, beryllium, thorium and uranium fluorides: LiF-BeF2-ThF4-UF4 (72-16-12-0.4 mol%). It had a peak operating temperature of 705 °C in the experiment, but could have operated at much higher temperatures, since the boiling point of the molten salt was in excess of 1400 °C.

Aqueous solutions of uranyl salts

The aqueous homogeneous reactors (AHRs) use a solution of uranyl sulfate or other uranium salt in water. Historically, AHRs have all been small research reactors, not large power reactors. An AHR known as the Medical Isotope Production System is being considered for production of medical isotopes.[3]

Common physical forms of nuclear fuel

Uranium dioxide (UO2) powder is compacted to cylindrical pellets and sintered at high temperatures to produce ceramic nuclear fuel pellets with a high density and well defined physical properties and chemical composition. A grinding process is used to achieve a uniform cylindrical geometry with narrow tolerances. Such fuel pellets are then stacked and filled into the metallic tubes. The metal used for the tubes depends on the design of the reactor. Stainless steel was used in the past, but most reactors now use a zirconium alloy which, in addition to being highly corrosion-resistant, has low neutron absorption. The tubes containing the fuel pellets are sealed: these tubes are called fuel rods. The finished fuel rods are grouped into fuel assemblies that are used to build up the core of a power reactor.

Cladding is the outer layer of the fuel rods, standing between the coolant and the nuclear fuel. It is made of a corrosion-resistant material with low absorption cross section for thermal neutrons, usually Zircaloy or steel in modern constructions, or magnesium with small amount of aluminium and other metals for the now-obsolete Magnox reactors. Cladding prevents radioactive fission fragments from escaping the fuel into the coolant and contaminating it.

-

Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) photo of unirradiated (fresh) fuel pellets.

-

NRC photo of fresh fuel pellets ready for assembly.

-

NRC photo of fresh fuel being inspected.

PWR fuel

Pressurized water reactor (PWR) fuel consists of cylindrical rods put into bundles. A uranium oxide ceramic is formed into pellets and inserted into Zircaloy tubes that are bundled together. The Zircaloy tubes are about 1 cm in diameter, and the fuel cladding gap is filled with helium gas to improve the conduction of heat from the fuel to the cladding. There are about 179-264 fuel rods per fuel bundle and about 121 to 193 fuel bundles are loaded into a reactor core. Generally, the fuel bundles consist of fuel rods bundled 14×14 to 17×17. PWR fuel bundles are about 4 meters long. In PWR fuel bundles, control rods are inserted through the top directly into the fuel bundle. The fuel bundles usually are enriched several percent in 235U. The uranium oxide is dried before inserting into the tubes to try to eliminate moisture in the ceramic fuel that can lead to corrosion and hydrogen embrittlement. The Zircaloy tubes are pressurized with helium to try to minimize pellet-cladding interaction which can lead to fuel rod failure over long periods.

BWR fuel

In boiling water reactors (BWR), the fuel is similar to PWR fuel except that the bundles are "canned". That is, there is a thin tube surrounding each bundle. This is primarily done to prevent local density variations from affecting neutronics and thermal hydraulics of the reactor core. In modern BWR fuel bundles, there are either 91, 92, or 96 fuel rods per assembly depending on the manufacturer. A range between 368 assemblies for the smallest and 800 assemblies for the largest U.S. BWR forms the reactor core. Each BWR fuel rod is backfilled with helium to a pressure of about three atmospheres (300 kPa).

CANDU fuel

CANDU fuel bundles are about a half meter long and 10 cm in diameter. They consist of sintered (UO2) pellets in zirconium alloy tubes, welded to zirconium alloy end plates. Each bundle is roughly 20 kg, and a typical core loading is on the order of 4500-6500 bundles, depending on the design. Modern types typically have 37 identical fuel pins radially arranged about the long axis of the bundle, but in the past several different configurations and numbers of pins have been used. The CANFLEX bundle has 43 fuel elements, with two element sizes. It is also about 10 cm (4 inches) in diameter, 0.5 m (20 in) long and weighs about 20 kg (44 lb) and replaces the 37-pin standard bundle. It has been designed specifically to increase fuel performance by utilizing two different pin diameters. Current CANDU designs do not need enriched uranium to achieve criticality (due to their more efficient heavy water moderator), however, some newer concepts call for low enrichment to help reduce the size of the reactors.

Less-common fuel forms

Various other nuclear fuel forms find use in specific applications, but lack the widespread use of those found in BWRs, PWRs, and CANDU power plants. Many of these fuel forms are only found in research reactors, or have military applications.

Magnox fuel

Magnox reactors are pressurised, carbon dioxide–cooled, graphite-moderated reactors using natural uranium (i.e. unenriched) as fuel and Magnox alloy as fuel cladding. Working pressure varies from 6.9 to 19.35 bar for the steel pressure vessels, and the two reinforced concrete designs operated at 24.8 and 27 bar. Magnox alloy consists mainly of magnesium with small amounts of aluminium and other metals—used in cladding unenriched uranium metal fuel with a non-oxidising covering to contain fission products. Magnox is short for Magnesium non-oxidising. This material has the advantage of a low neutron capture cross-section, but has two major disadvantages:

- It limits the maximum temperature, and hence the thermal efficiency, of the plant.

- It reacts with water, preventing long-term storage of spent fuel under water.

Magnox fuel incorporated cooling fins to provide maximum heat transfer despite low operating temperatures, making it expensive to produce. While the use of uranium metal rather than oxide made reprocessing more straightforward and therefore cheaper, the need to reprocess fuel a short time after removal from the reactor meant that the fission product hazard was severe. Expensive remote handling facilities were required to address this danger.

TRISO fuel

Tristructural-isotropic (TRISO) fuel is a type of micro fuel particle. It consists of a fuel kernel composed of UOX (sometimes UC or UCO) in the center, coated with four layers of three isotropic materials. The four layers are a porous buffer layer made of carbon, followed by a dense inner layer of pyrolytic carbon (PyC), followed by a ceramic layer of SiC to retain fission products at elevated temperatures and to give the TRISO particle more structural integrity, followed by a dense outer layer of PyC. TRISO fuel particles are designed not to crack due to the stresses from processes (such as differential thermal expansion or fission gas pressure) at temperatures up to and beyond 1600 °C, and therefore can contain the fuel in the worst of accident scenarios in a properly designed reactor. Two such reactor designs are the pebble-bed reactor (PBR), in which thousands of TRISO fuel particles are dispersed into graphite pebbles, and the prismatic-block gas-cooled reactor (such as the GT-MHR), in which the TRISO fuel particles are fabricated into compacts and placed in a graphite block matrix. Both of these reactor designs are high temperature gas reactors (HTGRs). These are also the basic reactor designs of very-high-temperature reactors (VHTRs), one of the six classes of reactor designs in the Generation IV initiative that is attempting to reach even higher HTGR outlet temperatures.

TRISO fuel particles were originally developed in the United Kingdom as part of the DRAGON project. The inclusion of the SiC as diffusion barrier was first suggested by D. T. Livey.[4] The first nuclear reactor to use TRISO fuels was the DRAGON reactor and the first powerplant was the THTR-300. Currently, TRISO fuel compacts are being used in the experimental reactors, the HTR-10 in China, and the HTTR in Japan.

QUADRISO fuel

In QUADRISO particles a burnable neutron poison (europium oxide or erbium oxide or carbide) layer surrounds the fuel kernel of ordinary TRISO particles to better manage the excess of reactivity. If the core is equipped both with TRISO and QUADRISO fuels, at beginning of life neutrons do not reach the fuel of the QUADRISO particles because they are stopped by the burnable poison. After irradiation, the poison depletes and neutrons stream into the fuel kernel of QUADRISO particles inducing fission reactions. This mechanism compensates fuel depletion of ordinary TRISO fuel. In the generalized QUADRISO fuel concept the poison can eventually be mixed with the fuel kernel or the outer pyrocarbon. The QUADRISO concept has been conceived at Argonne National Laboratory.

RBMK fuel

RBMK reactor fuel was used in Soviet-designed and built RBMK-type reactors. This is a low-enriched uranium oxide fuel. The fuel elements in an RBMK are 3 m long each, and two of these sit back-to-back on each fuel channel, pressure tube. Reprocessed uranium from Russian VVER reactor spent fuel is used to fabricate RBMK fuel. Following the Chernobyl accident, the enrichment of fuel was changed from 2.0% to 2.4%, to compensate for control rod modifications and the introduction of additional absorbers.

CerMet fuel

CerMet fuel consists of ceramic fuel particles (usually uranium oxide) embedded in a metal matrix. It is hypothesized that this type of fuel is what is used in United States Navy reactors. This fuel has high heat transport characteristics and can withstand a large amount of expansion.

Plate-type fuel

Plate-type fuel has fallen out of favor over the years. Plate-type fuel is commonly composed of enriched uranium sandwiched between metal cladding. Plate-type fuel is used in several research reactors where a high neutron flux is desired, for uses such as material irradiation studies or isotope production, without the high temperatures seen in ceramic, cylindrical fuel. It is currently used in the Advanced Test Reactor (ATR) at Idaho National Laboratory, and the nuclear research reactor at the University of Massachusetts Lowell Radiation Laboratory.

Sodium-bonded fuel

Sodium-bonded fuel consists of fuel that has liquid sodium in the gap between the fuel slug (or pellet) and the cladding. This fuel type is often used for sodium-cooled liquid metal fast reactors. It has been used in EBR-I, EBR-II, and the FFTF. The fuel slug may be metallic or ceramic. The sodium bonding is used to reduce the temperature of the fuel.

Spent nuclear fuel

Used nuclear fuel is a complex mixture of the fission products, uranium, plutonium, and the transplutonium metals. In fuel which has been used at high temperature in power reactors it is common for the fuel to be heterogeneous; often the fuel will contain nanoparticles of platinum group metals such as palladium. Also the fuel may well have cracked, swollen, and been heated close to its melting point. Despite the fact that the used fuel can be cracked, it is very insoluble in water, and is able to retain the vast majority of the actinides and fission products within the uranium dioxide crystal lattice.

Oxide fuel under accident conditions

Two main modes of release exist, the fission products can be vaporised or small particles of the fuel can be dispersed.

Fuel behavior and post-irradiation examination

Post-Irradiation Examination (PIE) is the study of used nuclear materials such as nuclear fuel. It has several purposes. It is known that by examination of used fuel that the failure modes which occur during normal use (and the manner in which the fuel will behave during an accident) can be studied. In addition information is gained which enables the users of fuel to assure themselves of its quality and it also assists in the development of new fuels. After major accidents the core (or what is left of it) is normally subject to PIE to find out what happened. One site where PIE is done is the ITU which is the EU centre for the study of highly radioactive materials.

Materials in a high-radiation environment (such as a reactor) can undergo unique behaviors such as swelling and non-thermal creep. If there are nuclear reactions within the material (such as what happens in the fuel), the stoichiometry will also change slowly over time. These behaviors can lead to new material properties, cracking, and fission gas release.

The thermal conductivity of uranium dioxide is low; it is affected by porosity and burn-up. The burn-up results in fission products being dissolved in the lattice (such as lanthanides), the precipitation of fission products such as palladium, the formation of fission gas bubbles due to fission products such as xenon and krypton and radiation damage of the lattice. The low thermal conductivity can lead to overheating of the center part of the pellets during use. The porosity results in a decrease in both the thermal conductivity of the fuel and the swelling which occurs during use.

According to the International Nuclear Safety Center the thermal conductivity of uranium dioxide can be predicted under different conditions by a series of equations.

The bulk density of the fuel can be related to the thermal conductivity

Where ρ is the bulk density of the fuel and ρtd is the theoretical density of the uranium dioxide.

Then the thermal conductivity of the porous phase (Kf) is related to the conductivity of the perfect phase (Ko, no porosity) by the following equation. Note that s is a term for the shape factor of the holes.

- Kf = Ko(1 − p/1 + (s − 1)p)

Rather than measuring the thermal conductivity using the traditional methods such as Lees' disk, the Forbes' method, or Searle's bar, it is common to use Laser Flash Analysis where a small disc of fuel is placed in a furnace. After being heated to the required temperature one side of the disc is illuminated with a laser pulse, the time required for the heat wave to flow through the disc, the density of the disc, and the thickness of the disk can then be used to calculate and determine the thermal conductivity.

- λ = ρCpα

If t1/2 is defined as the time required for the non illuminated surface to experience half its final temperature rise then.

- α = 0.1388 L2/t1/2

- L is the thickness of the disc

Radioisotope decay fuels

Radioisotope battery

The terms atomic battery, nuclear battery and radioisotope battery are used interchangeably to describe a device which uses the radioactive decay to generate electricity. These systems use radioisotopes that produce low energy beta particles or sometimes alpha particles of varying energies. Low energy beta particles are needed to prevent the production of high energy penetrating bremsstrahlung radiation that would require heavy shielding. Radioisotopes such as plutonium-238, curium-242, curium-244 and strontium-90 have been used. Tritium, nickel-63, promethium-147, and technetium-99 have been tested.

There are two main categories of atomic batteries: thermal and non-thermal. The non-thermal atomic batteries, which have many different designs, exploit charged alpha and beta particles. These designs include the direct charging generators, betavoltaics, the optoelectric nuclear battery, and the radioisotope piezoelectric generator. The thermal atomic batteries on the other hand, convert the heat from the radioactive decay to electricity. These designs include thermionic converter, thermophotovoltaic cells, alkali-metal thermal to electric converter, and the most common design, the radioisotope thermoelectric generator.

Radioisotope thermoelectric generators

A radioisotope thermoelectric generator (RTG) is a simple electrical generator which converts heat into electricity from a radioisotope using an array of thermocouples.

238Pu has become the most widely used fuel for RTGs, in the form of plutonium dioxide. It has a half-life of 87.7 years, reasonable energy density, and exceptionally low gamma and neutron radiation levels. Some Russian terrestrial RTGs have used 90Sr; this isotope has a shorter half-life and a much lower energy density, but is cheaper. Early RTGs, first built in 1958 by the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission, have used 210Po. This fuel provides phenomenally huge energy density, (a single gram of polonium-210 generates 140 watts thermal) but has limited use because of its very short half-life and gamma production, and has been phased out of use for this application.

Radioisotope heater units (RHU)

Radioisotope heater units normally provide about 1 watt of heat each, derived from the decay of a few grams of plutonium-238. This heat is given off continuously for several decades.

Their function is to provide highly localised heating of sensitive equipment (such as electronics in outer space). The Cassini–Huygens orbiter to Saturn contains 82 of these units (in addition to its 3 main RTG's for power generation). The Huygens probe to Titan contains 35 devices.

Fusion fuels

Fusion fuels include deuterium (2H) and tritium (3H) as well as helium-3 (3He). Many other elements can be fused together, but the larger electrical charge of their nuclei means that much higher temperatures are required. Only the fusion of the lightest elements is seriously considered as a future energy source. Fusion of the lightest atom, 1H hydrogen, as is done in the Sun and stars, has also not been considered practical on Earth. Although the energy density of fusion fuel is even higher than fission fuel, and fusion reactions sustained for a few minutes have been achieved, utilizing fusion fuel as a net energy source remains a theoretical possibility.[5]

First-generation fusion fuel

Deuterium and tritium are both considered first-generation fusion fuels; they are the easiest to fuse, because the electrical charge on their nuclei is the lowest of all elements. The three most commonly cited nuclear reactions that could be used to generate energy are:

- 2H + 3H

n (14.07 MeV) + 4He (3.52 MeV)

n (14.07 MeV) + 4He (3.52 MeV)

- 2H + 2H

n (2.45 MeV) + 3He (0.82 MeV)

n (2.45 MeV) + 3He (0.82 MeV)

- 2H + 2H

p (3.02 MeV) + 3H (1.01 MeV)

p (3.02 MeV) + 3H (1.01 MeV)

Second-generation fusion fuel

Second-generation fuels require either higher confinement temperatures or longer confinement time than those required of first-generation fusion fuels, but generate fewer neutrons. Neutrons are an unwanted byproduct of fusion reactions in an energy generation context, because they are absorbed by the walls of a fusion chamber, making them radioactive. They cannot be confined by magnetic fields, because they are not electrically charged. This group consists of deuterium and helium-3. The products are all charged particles, but there may be significant side reactions leading to the production of neutrons.

- 2H + 3He

p (14.68 MeV) + 4He (3.67 MeV)

p (14.68 MeV) + 4He (3.67 MeV)

Third-generation fusion fuel

Third-generation fusion fuels produce only charged particles in the primary reactions, and side reactions are relatively unimportant. Since a very small amount of neutrons is produced, there would be little induced radioactivity in the walls of the fusion chamber. This is often seen as the end goal of fusion research. 3He has the highest Maxwellian reactivity of any 3rd generation fusion fuel. However, there are no significant natural sources of this substance on Earth.

- 3He + 3He

2p + 4He (12.86 MeV)

2p + 4He (12.86 MeV)

Another potential aneutronic fusion reaction is the proton-boron reaction:

- p + 11B → 34He (8.7 MeV)

Under reasonable assumptions, side reactions will result in about 0.1% of the fusion power being carried by neutrons. With 123 keV, the optimum temperature for this reaction is nearly ten times higher than that for the pure hydrogen reactions, the energy confinement must be 500 times better than that required for the D-T reaction, and the power density will be 2500 times lower than for D-T.

See also

- Global Nuclear Energy Partnership

- Lists of nuclear disasters and radioactive incidents

- Nuclear fuel bank

- Nuclear fuel cycle

- Reprocessed uranium

- Uranium market

- Integrated Nuclear Fuel Cycle Information System

References

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑ "B&W Medical Isotope Production System". The Babcock & Wilcox Company. 2011-05-11.

- ↑ Price, M. S. T. (2012). "The Dragon Project origins, achievements and legacies". Nucl. Eng. Design 251: 60–68. doi:10.1016/j.nucengdes.2011.12.024.

- ↑ "Nuclear Fusion Power". World Nuclear Association. September 2009. Retrieved 2010-01-27.

External links

PWR fuel

- NEI fuel schematic

- Picture of a PWR fuel assembly

- Picture showing handling of a PWR bundle

- Mitsubishi nuclear fuel Co.

BWR fuel

- Picture of a "canned" BWR assembly

- Physical description of LWR fuel

- Links to BWR photos from the nuclear tourist webpage

CANDU fuel

- CANDU Fuel pictures and FAQ

- Basics on CANDU design

- The Evolution of CANDU Fuel Cycles and their Potential Contribution to World Peace

- CANDU Fuel-Management Course

- CANDU Fuel and Reactor Specifics (Nuclear Tourist)

- Candu Fuel Rods and Bundles

TRISO fuel

- TRISO fuel descripción

- Non-Destructive Examination of SiC Nuclear Fuel Shell using X-Ray Fluorescence Microtomography Technique

- GT-MHR fuel compact process

- Description of TRISO fuel for "pebbles"

- LANL webpage showing various stages of TRISO fuel production

- Method to calculate the temperature profile in TRISO fuel

QUADRISO fuel

CERMET fuel

- A Review of Fifty Years of Space Nuclear Fuel Development Programs

- Thoria-based Cermet Nuclear Fuel: Sintered Microsphere Fabrication by Spray Drying

- The Use of Molybdenum-Based Ceramic-Metal (CerMet) Fuel for the Actinide Management in LWRs

Plate type fuel

TRIGA fuel

Fusion fuel

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|