The Sword of Shannara

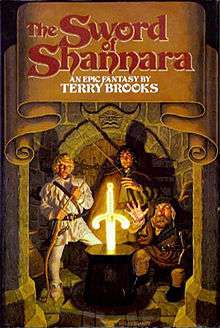

First hardcover edition (Random House) | |

| Author | Terry Brooks |

|---|---|

| Illustrator | The Brothers Hildebrandt |

| Cover artist | The Brothers Hildebrandt |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Series | Original Shannara Trilogy |

| Genre | Epic fantasy[1] |

| Publisher | Ballantine/Del Rey |

Publication date | 1977 |

| Media type | Print (Hardcover and Paperback) |

| Pages | 726 pp |

| ISBN | 0-345-24804-X (First edition) |

| Preceded by | First King of Shannara |

| Followed by | The Elfstones of Shannara |

The Sword of Shannara is a 1977 epic fantasy novel by Terry Brooks. It is the first book of the Original Shannara Trilogy, followed by The Elfstones of Shannara and The Wishsong of Shannara. Brooks was heavily influenced by J.R.R. Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings and began writing The Sword of Shannara in 1967. It took him seven years to complete, as he was writing the novel while attending law school. Ballantine Books used it to launch the company's new subsidiary Del Rey Books. Its success boosted the commercial expansion of the fantasy genre.

The novel interweaves two major plots into a fictional world called the Four Lands. One follows the protagonist Shea Ohmsford on his quest to obtain the Sword of Shannara and confront the Warlock Lord (the antagonist) with it. The other plot shadows Prince Balinor Buckhannah's attempt to oust his insane brother Palance from the throne of Callahorn while the country and its capital (Tyrsis) come under attack from overwhelming armies of the Warlock Lord. Throughout the novel, underlying themes appear of mundane heroism and nuclear holocaust.

Critics have derided the novel for being derivative of J.R.R. Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings. Some have accused Brooks of lifting the entire plot and many of his characters directly from Lord of the Rings; others have regarded the book more favorably and say that new writers often start by copying the style of established writers.

Plot summary

History

The Sword of Shannara's events take place 2000 years[2] after a Great War: nuclear holocaust has wiped out most of the planet. During this time, Mankind mutates into several distinct races: Men, Dwarves, Gnomes, and Trolls, all named after creatures from "age-old" myths. Also, the Elves begin to emerge after having been in seclusion and hiding for centuries. The warring that caused the holocaust is referred to as the "Great Wars" throughout the novel. These wars rearranged the planet's geographical attributes and wiped out most human life on Earth. Most advanced technology has been lost, but magic has been rediscovered.

A thousand years before The Sword of Shannara, an Elf named Galaphile gathers all of the people who still had some knowledge of the old world to Paranor to try to bring peace and order to all of the races. They name themselves the First Druid Council. Brona, a rogue Druid, and his followers leave, taking the Ildatch with them; this magical tome controls their minds. 250 years later, Brona begins the First War of the Races when he convinces all Men to attack the other races. He almost succeeds in seizing rule of the Four Lands, but the tide turns, and the war ends with his defeat and disappearance. The Druids divide the Four Lands among the races and become reclusive, withdrawing to Paranor because of their shame at the betrayal by one of their own members.

Two and a half centuries after the First War of the Races, Brona returns as the Warlock Lord, now with Skull Bearers as his servants. Chronicled in the prequel novel First King of Shannara, the Second War of the Races begins with the destruction of the Druid Order. A lone Druid, Bremen, forges a magical talisman to destroy the Warlock Lord; it is given to the Elven King, Jerle Shannara. As it takes the form of a blade, the talisman is named the Sword of Shannara. It succeeds in banishing the Warlock Lord. He is not killed, but his army is defeated by the combined armies of the Elves and Dwarves. Peace comes at a high price, interracial tension is renewed and the Druids have vanished.

Present

From Shady Vale to Paranor

Five centuries later, the Ohmsford family of Shady Vale in the Southland takes in the half-Elven child Shea. He takes the name Ohmsford and is raised as a brother to the family's son Flick. Becoming inseparable, the brothers run the family inn.

Some time later, the last Druid Allanon arrives in Shady Vale. Allanon warns the Ohmsford brothers that the Warlock Lord has returned to the Skull Kingdom in the Northland and is coming for Shea. As the last descendant of Jerle Shannara, Shea is the only one capable of wielding the Sword of Shannara against the Warlock Lord.

Allanon departs, leaving Shea three Blue Elfstones for protection. He tells Shea to flee at the sign of the Skull. A few weeks later, a creature bearing a symbol of a skull shows up: a Skull Bearer, one of the Warlock Lord's "winged black destroyers",[3] has arrived to search for Shea. The brothers are forced to flee with the Skull Bearer on their heels. They take refuge in the nearby city of Leah where they find Shea's friend Menion, the son of the city's lord. Menion decides to accompany the two, and he travels with them to Culhaven, to meet with Allanon. While at Culhaven, they are joined by a prince of Callahorn, Balinor Buckhannah, two elven brothers, Durin and Dayel Elessedil, and the dwarf Hendel.

The party sets out for Paranor. But along the way, Shea falls over a waterfall and becomes separated from the group. Allanon spurs the group to continue to Paranor. Once there, the party gets into a battle with minions of the Warlock Lord and find that the Sword of Shannara has already been removed. The party then learns of the Warlock Lord's invasion of the Southland, and decide to split up to do what they can to stop it.

In the Southland

Disguised by Allanon, Flick infiltrates the enemy camp and rescues the captive Elven King, Eventine Elessedil; at the same time, in Kern, Menion saves a woman named Shirl Ravenlock and falls in love with her. They organize an evacuation of Kern before the Northland army reaches the city.

Balinor returns to Tyrsis to activate the Border Legion only to find that it has been disbanded. Balinor is then imprisoned by his insane brother Palance Buckhannah, who has taken control of Callahorn's rule. His advisor, Stenmin, has driven Palance insane with drugs, making him his pawn. With help from Menion, Balinor escapes and confronts both Palance and Stenmin. Practically cornered, Stenmin stabs Palance as a distraction and flees.

Now commanded by Balinor, Callahorn's reformed Border Legion marches out of Tyrsis and engages the Northland army at the Mermiddon River, killing many Northlanders before being forced to pull back; the Border Legion retreats to Tyrsis and make preparations for defense. During the siege of Tyrsis, Hendel and Menion come upon Stenmin and some of his supporters. Hendel is killed, but Menion kills Stenmin. After three days, the Border Legion is beaten back from the Outer Wall of Tyrsis as a result of treachery—the wall falls when the traitors destroy the locks on the main gate, jamming it open. At the defenders' last stand on the Bridge of Sendic, the Northlanders abruptly break and run.

In the Northland

After being captured by Gnomes, Shea is rescued by the one-handed thief Panamon Creel and his mute Troll companion Keltset Mallicos. Journeying to the Northland, they reach the Skull Kingdom, where the insane Gnome deserter Orl Fane has carried the Sword of Shannara.

Infiltrating the Warlock Lord's fortress in the Skull Mountain, Shea reaches the sword and unsheathes it. He learns about its true power, the ability to confront those with the truth about their lives. The Warlock Lord materializes and tries to destroy Shea, but the youth stands his ground and confronts his enemy with the sword. Although immune to physical weapons, the Warlock Lord vanishes after being forced to confront the truth about himself: he had deluded himself into believing that he is immortal, but this is impossible. The Sword forces him to confront this paradox, and it kills him.

Keltset sacrifices himself to save his companions during the Skull Kingdom's destruction. In the south, the Northland army retreats after the Warlock Lord's downfall. Allanon saves Shea's life and reveals himself as Bremen's centuries-old son, before disappearing to sleep. Peace returns to the Four Lands. Balinor takes up his country's rule, while Dayel and Durin return to the Westland, and Menion returns to Leah with Shirl. Shea and Flick reunite and return to Shady Vale.

Characters

Left to right: Menion, Dayel and Durin, Hendel (foreground),

Balinor (background), Allanon (background), Shea, Flick.

- Shea Ohmsford, the protagonist, Flick's adopted brother and the only remaining descendant of Jerle Shannara. Shea must find an ancient magical sword, the Sword of Shannara, and use it to destroy the antagonist, the Warlock Lord. A major theme of this novel revolves around Shea—part of his quest includes finding a belief in himself.[4] This is a search that every subsequent Brooks protagonist must undergo.[4]

- Flick Ohmsford, Shea's brother. He helps Shea escape Shady Vale and 'tags along' with the group that goes to recover the Sword. He rescues Eventine "solo"[4] after Allanon disguises him as a Gnome.

- Menion Leah, a friend of Shea and the Prince of the small country of Leah. He guides Shea and Flick to Culhaven after their escape of Shady Vale and the Skull Bearer. He is the first of many from the House of Leah to befriend a member of the Ohmsford family.[5]

- Allanon, a Druid who has been alive for around 400 years through the use of Druid Sleep. He guides and mentors the group on their quest to find the Sword. Allanon has been described as a parallel to Merlin from Arthurian legend.[6]

- Balinor Buckhannah, the Crown Prince of the country of Callahorn and the "charismatic commander of [the] Border Legion".[4] He left the capital, Tyrsis, after a fight with his insane brother, Palance; upon returning, he was thrown into a dungeon by him.

- Hendel, a "taciturn"[4] Dwarf warrior. He first appears in the novel when he saves Menion Leah from a Siren, and was part of the company that went to find the Sword.

- Durin Elessedil, the older brother of Dayel and cousin to King Eventine. He was part of the company that went to find the Sword.

- Dayel Elessedil, the younger brother of Durin and cousin to King Eventine. He was part of the company that went to find the Sword.

- Stenmin, a traitor to Callahorn now working for the Warlock Lord. He poisoned both Palance and Ruhl Buckhannah, the King of Callahorn, eventually killing Ruhl and driving Palance insane.

- Palance Buckhannah, the brother of Balinor Buckhannah and a prince of Callahorn. He was driven insane as a result of drugs fed to him by Stenmin, and at his urging, took control of Callahorn when his father 'took ill'.

- Panamon Creel, a one-handed "con man"[4] wanderer whose left hand is now a pike. He saved Shea from a patrol of Gnomes. The inspiration from his character came directly from Rupert of Hentzau from The Prisoner of Zenda, by Anthony Hope.[7]

- Keltset Mallicos, Panamon's mute companion. He is mute as a result of the Warlock Lord. He saves Panamon and Shea after they were captured by Trolls—he was awarded the Black Irix, the highest honor any Troll can receive, and therefore is considered incapable of treachery. The Trolls then helped them get to Skull Mountain so that Shea could confront the Warlock Lord.

- Brona (the Warlock Lord), the former Druid and antagonist of the novel. In days long ago, Brona was a Druid before he was subverted by dark magic. He believes that he is immortal, and so he still lives. When he was confronted with the power of the Sword, "truth", he was forced to see that he was really dead, and immediately disappeared.

- Skull Bearers, "winged black destroyers"[3] who "sacrificed their humanity"[3] to become the Warlock Lord's most trusted servants. They fly around at different points of the novel, demoralizing troops. They are usually seen only at night, though one does fly during the day over the city of Tyrsis on the last day of the battle.

- Shirl Ravenlock, the daughter of the ruler of Kern. She was kidnapped by Stenmin to prevent her from reaching Palance, who thinks that he is in love with her. As such, she is the only person who can get through his drug-induced craziness. She eventually falls in love with Menion Leah. She is one of only two women to appear directly in the book, with the other being the Siren.[4]

- Orl Fane, a "Gollum-like"[8] Gnome who "covets the Sword as Gollum does the ring."[8] He stole the Sword and forced Panamon, Keltset and Shea to track him down. He was driven insane and killed by the Warlock Lord after he took control of his mind and forced him to try to take the Sword.

Background

Brooks began writing The Sword of Shannara in 1967[9] when he was twenty-three years old.[10] He started writing the novel to challenge himself and as a way of staying "sane" while he attended law school at Washington and Lee University.[9][11] Brooks had been a writer since high school,[12] but he had never found 'his' genre: "I tried my hand at science fiction, westerns, war stories, you name it. All those efforts ... weren't very good."[10] When he was starting college, he was given a copy of Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings to read for the first time. From then on, Brooks knew that he had found a genre he could write in.[10] Writing Sword took seven years, as Brooks worked on it only sporadically while also completing his law school courses and rewrote it many times.[11][13]

Brooks initially submitted his manuscript to DAW Books, whose editor Donald A. Wollheim rejected it and recommended submission to Judy-Lynn del Rey at Ballantine Books instead.[9] Ballantine Books accepted The Sword of Shannara in November 1974.[9] Brooks' editor was Lester del Rey, who used the book to launch Ballantine's new Del Rey Books imprint/subsidiary.[14] Del Rey chose it because he felt that it was "the first long epic fantasy adventure which had any chance of meeting the demands of Tolkien readers for similar pleasures."[15]

In 1977, The Sword of Shannara was simultaneously released as a trade paperback[Note 1] by Ballantine Books and hardback[Note 2] by Random House.[16][17] The Brothers Hildebrandt, who had previously done illustration work for the work of Tolkien, was asked to make the cover. Greg Hildebrandt remembers the Del Reys as being "obsessed with the project. It was their baby."[18] The novel was a commercial success, becoming the first fantasy fiction novel to appear on The New York Times trade paperback bestseller list.[14][19][20]

The original inspiration for The Sword of Shannara was Brooks' desire to put "Tolkien's magic and fairy creatures [into] the worlds of Walter Scott and [Alexander] Dumas".[9] Later, other inspirations jumped onto Brooks' bandwagon. Brooks was inspired by J.R.R. Tolkien The Lord of the Rings and adventure fiction such as Alexandre Dumas' The Three Musketeers, Robert Louis Stevenson's Treasure Island, Arthur Conan Doyle's The White Company and Walter Scott's Ivanhoe.[9][21]

Brooks decided not to use historical settings like these works.[21] He instead followed Tolkien's use of a fantasy setting instead:[21]

I would set my adventure story in an imaginary world, a vast, sprawling, mythical world like that of Tolkien, filled with magic that had replaced science and races that had evolved from Man. But I was not Tolkien and did not share his background in academia or his interest in cultural study. So I would eliminate the poetry and songs, the digressions on the ways and habits of types of characters, and the appendices of language and backstory that characterized and informed Tolkien's work. I would write the sort of straightforward adventure story that barreled ahead, picking up speed as it went, compelling a turning of pages until there were no more pages to be turned.

He admits that he was very influenced by The Lord of the Rings when writing it, being his first novel, but that he has evolved his own style since:[22]

Tolkien approached it as an academic, and he was writing it as an academic effort, not as popular fiction. I’m a popular fiction writer, that's the way I approached it. And I think that you're right, too, about the fact that I was heavily under the influence of Tolkien when I wrote Sword of Shannara and it shows in that particular book. But I've really gotten a long way away from Tolkien these days and not very many people come up to me any more and say, “Well, gee, you're writing an awful lot like Tolkien.” They don’t say that any more.

Brooks also made decisions about his novel's characterization and use of magic, saying that the magic "couldn't be dependable or simply good or bad".[9] Also, he wanted to blur the distinctions between good and evil, "because life simply [doesn't] work that way."[9] He wanted to ensure that readers would identify with his protagonist, Shea, which he accomplished by casting Shea as "a person simply trying to muddle through".[9]

Major themes

"Ordinary men placed in extraordinary circumstances"[23] is a prevalent theme in The Sword of Shannara. Brooks credits Tolkien with introducing this theme of mundane heroism into fantasy literature and influencing his own fiction. "[M]y protagonists are cut from the same bolt of cloth as Bilbo and Frodo Baggins. It was Tolkien's genius to reinvent the traditional epic fantasy by making the central character neither God nor hero, but a simple man in search of a way to do the right thing. ... I was impressed enough by how it had changed the face of epic fantasy that I never gave a second thought to not using it as the cornerstone of my own writing."[23]

The Sword of Shannara is set in a post-apocalyptic Earth,[14] where chemical and nuclear holocaust devastated the land in the distant past.[24][25] Due to the numerous references in Sword to this catastrophe, Brooks was asked a question about whether he thought that his 'prediction' might come true. He answered:[26]

I don't see myself as a negative person, so I don't think I've ever thought we would destroy ourselves. But it does worry me that not only are we capable of [nuclear war], but [we also] flirt with the idea periodically. One mistake, after all . . . Anyway, I used the background in [The] Sword of Shannara more in a cautionary vein than as a prophecy. Also, it was necessary to destroy civilization in order to take a look at what it would mean to have to build it back up again using magic. A civilization once destroyed by misuse of power is a bit wary the second time out about what new power can do.

Environment plays a role in all of the Shannara novels: "Environment is a character in my story and almost always plays a major role in affecting the story's outcome. I have always believed that fantasy, in particular, because it takes place in an imaginary world with at least some imaginary characters, needs to make the reader feel at home in the setting. That means bringing the setting alive for the reader, which is what creating environment as a character is really all about." However, Brooks believes that Sword was more about behavioral issues and personal sacrifice.[10]

Literary significance and reception

The Sword of Shannara received mixed reviews following its publication, most of which remarked on its similarity to J. R. R. Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings. Choice stated that the novel was an "exceptionally well-written, very readable...entrance into the genre...[that] will be accepted by most teenagers."[27][28] Marshall Tymn also thought that it contained quality prose. Tymn believed that Sword followed Lord of the Rings too closely, but he also cited some of the differences, such as the use of a post-holocaust setting with the races that sprang from that, and the "entertaining conartist, Panamon Creel, ... and ... an unexpected ending springing from the nature of the sword."[25][28] Cathi Dunn MacRae assessed all of Brooks' works in her 1998 book Presenting Young Adult Fantasy Fiction. On The Sword of Shannara, she thought this:[5]

In this postholocaust world of our future, Brooks parallels the mystic arts ... with science, two powers that are not good or evil but become either by the way we use them. Evil is a corruption of truth, erupting from the selfish use of power for one's own ends. Good arises from the insistence on truth, allowing us to realize our indelible bonds with others of all races, and our connection with nature and earth. Anything unnatural is evil, such as the Warlock Lord's immortality, which recalls similar abuse of nature by Le Guin's Cob and by Barbara Hambly's wizard Suraklin.

One of Brooks' strengths is his plot's momentum, maintained through cliffhangers, unexpected twists of fortune, and the dance of many characters' constant movements. This brisk pace alters when characters pause to ruminate, which draws out suspense and reveals motivation. However, first novelist Brooks as puppet master is not always in control of the strings. With no single point of view centered in one character, his focus is diffused, and the anxieties and realizations of each character beg[an] to sound the same, blurring their identities with repetition.

Sword and The Lord of the Rings

The Sword of Shannara has drawn extensive criticism from critics who believe that Brooks derived too much of his novel from Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings. In 1978, influential fantasy editor Lin Carter denounced The Sword of Shannara as "the single most cold-blooded, complete rip-off of another book that I have ever read".[29] Elaborating on his disapproval of the book, Carter wrote that "Terry Brooks wasn't trying to imitate Tolkien's prose, just steal his story line and complete cast of characters, and [Brooks] did it with such clumsiness and so heavy-handedly, that he virtually rubbed your nose in it."[29] Roger C. Schlobin was kinder in his assessment, though he still thought that The Sword of Shannara was a disappointment because of its similarities to The Lord of the Rings.[30] Brian Attebery accused The Sword of Shannara of being "undigested Tolkien" which was "especially blatant in its point-for-point correspondence" with The Lord of the Rings.[31] In an educational article on writing, author Orson Scott Card cited The Sword of Shannara as a cautionary example of overly derivative writing, finding the work "artistically displeasing" for this reason.[32]

Assessing The Sword of Shannara three decades after its publication, Tolkien scholar Tom Shippey agreed with Attebery, as Shippey found that the novel was distinctive for "the dogged way in which it follow[ed] Tolkien point for point".[33] Within Brooks' novel, Shippey located "analogues" for Tolkien characters such as Sauron (Brona), Gandalf (Allanon), the Hobbits (Shea and Flick), Aragorn (Menion), Boromir (Balinor), Gimli (Hendel), Legolas (Durin and Dayel), Gollum (Orl Fane), the Barrow-wight (Mist Wraith), and the Nazgûl (Skull Bearers), among others.[33] He also found plot similarities to events in The Lord of the Rings such as the Fellowship of the Ring's formation and adventures, the journeys to Rivendell (Culhaven) and Lothlórien (Storlock), Gandalf's (Allanon) fall in Moria (Paranor) and subsequent reappearance, and the Rohirrim's arrival at the Battle of the Pelennor Fields (Battle of Tirsys), among others.[33] Avoiding direct commentary on the book's quality, Shippey attributed the book's success to the post-Tolkienian advent of the fantasy genre: "What The Sword of Shannara seems to show is that many readers had developed the taste ... for heroic fantasy so strongly that if they could not get the real thing they would take any substitute, no matter how diluted."[33]

Terry Brooks has said that Tolkien's works were a major influence in his writing,[34] though he has also said that Tolkien was not his only influence. Other influences included his editor Lester del Rey, as well as the many different books which he had read over his life. Also, mythology and ancient civilizations that he had learned about in school gave him a wealth of knowledge from which he drew. Many of these influences are reflected in Brooks' works.[10]

In a 2001 Interzone essay, author Gene Wolfe defended Brooks' derivation of material from Tolkien: "Terry Brooks has often been disparaged for imitating Tolkien, particularly by those reviewers who find his books inferior to Tolkien's own. I can say only that I wish there were more imitators -- we need them -- and that all imitations of so great an original must necessarily be inferior."[35] In a commentary for The New York Times Book Review, Frank Herbert, author of the science fiction novel Dune, also defended Brooks, saying:[36]

Don't fault Brooks for entering the world of letters through the Tolkien door. Every writer owes a similar debt to those who have come before. Some will admit it. Tolkien's debt was equally obvious. The classical myth structure is deeply embedded in Western society.

That's why you should not be surprised at finding these elements in The Sword of Shannara. Yes, you will find here the young prince in search of his grail; the secret (and not always benign) powers of nature; the magician; the wise old man; the witch mother; the malignant threat from a sorcerer; the holy talisman; the virgin queen; the fool (in the ancient tarot sense of the one who asks the disturbing questions) and all of the other Arthurian trappings.

What Brooks has done is to present a marvelous exposition of why the idea is not the story. Because of the popular assumption (which assumes mythic proportions of its own) that ideas form 99 percent of a story, writers are plagued by that foolish question, "Where do you get your ideas?" Brooks demonstrates that it doesn't matter where you get the idea; what matters is that you tell a rousing story.

Herbert said that "Brooks revert[ed] to his own style ... somewhere around Chapter 20"[36] and remarked upon what Brooks did not take from Tolkien:[36]

In the last chapters, you get the Brooksian innovations—the Rock Troll [Keltset], who is deep and mute and whose actions, thus, are far more important than any words could be; the Grim Druid, who really changes character in the second half of the book, becoming far more complex and devious (the name Allanon should give you a clue); Balinor, the Prince of Callahorn, whose role breaks with myth tradition; the Warlock Lord, who pretty much fills the traditional role of evil—but that's what you expect of evil and it doesn't blight a good story.

Herbert also praised the characters of evil in the book: "Ah, the monsters in this book. Brooks creates distillations of horror that hark back to childhood's shadows, when the most important thing about a fearful creature was that you didn't know its exact shape and intent. You only knew that it wanted you. The black-winged skull bearer, for instance, is more than a euphemism for death.[36] In a 2001 article for Seattle Weekly, David Massengill also commented upon Brooks' main characters, calling them "idiosyncratic adventurers."[19]

Other contemporary newspapers took separate sides on the Sword and Lord of the Rings issue. John Batchelor, writing for The Village Voice, thought that it was the weakest of the 1977 surge in fantasy, ranking it below Stephen R. Donaldson's The Chronicles of Thomas Covenant, the Unbeliever, Seamus Cullen's Astra and Flondrix, and The Silmarillion, edited by Christopher Tolkien, while commenting that it "unabashedly cop[ied]" Lord of the Rings. However, he also believed that it was serviceable, simply because there is something exciting about sending off a group to face evil alone.[37] Taking the opposite stance, L.V. Keptert in the Sydney Morning Herald believed that the book was similar enough to Tolkien that it would draw the many fans of that book to Sword, but it was only similar on a most basic level, and a valid comparison could not be made between the two.[38] The Pittsburgh Press took a similar stance, saying that Sword embodied the Tolkien spirit and tradition but was quite able to stand apart from Lord of the Rings.[39]

Book impact

The Sword of Shannara sold about 125,000 copies in its first month in print.[40] This success provided a major boost to the fantasy genre.[41]

Louise J. Winters writes that "until Shannara, no fantasy writer except J. R. R. Tolkien had made such an impression on the general public."[42] Critic David Pringle credits Brooks for "demonstrat[ing] in 1977 that the commercial success of Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings had not been a fluke, and that fantasy really did have the potential to become a mass-market genre".[43] With Stephen R. Donaldson's The Chronicles of Thomas Covenant, the Unbeliever, The Sword of Shannara ushered in "the era of the big commercial fantasy"[44] and helped make epic fantasy the leading fantasy subgenre.[44] The Sword of Shannara and its sequels helped inspire later versions of Dungeons and Dragons.[45]

Television adaptation

The Shannara books were to be adapted by Mike Newell, the director Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire, but he left the project.[46] The books eventually were adapted for television by Farah Films and executive produced by Brooks, Dan Farah, and Stewart Till. This begins with Elfstones, leaving Sword for later.[47] The Shannara Chronicles premiered on American television network MTV on January 5, 2016.

Notes

References

- ↑ "Once Over". The English Journal (National Council of Teachers of English) 66 (8): 82. November 1977.

- ↑ Indomitable summary at Google books. Google Books. 2008. Retrieved 2008-09-15.

- 1 2 3 Young Adult Fantasy Fiction, 74.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Young Adult Fantasy Fiction, 76.

- 1 2 Young Adult Fantasy Fiction, 75.

- ↑ Young Adult Fantasy Fiction, 79.

- ↑ Young Adult Fantasy Fiction, 80.

- 1 2 Young Adult Fantasy Fiction, 82.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Brooks, Terry (2002) [1991]. "Author's Note". Archived from the original on 2008-03-21. Retrieved 2008-06-24.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Brooks, Terry (1999–2008). "Ask Terry Q&A - Writing". Retrieved 2008-09-14.

- 1 2 Brooks, Terry (March 2009). "Ask Terry Q&A - March 2009". Retrieved 2009-07-23.

- ↑ Speakman, Shawn (1999–2008). "Terry Brooks - Biography". terrybrooks.net. Retrieved 2008-08-26.

- ↑ Sometimes the Magic Works, 189

- 1 2 3 Clute, John (1997/1999). "Brooks, Terry". The Encyclopedia of Fantasy. New York: St. Martin's Griffin. p. 142. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ The World of Science Fiction, 302

- ↑ The World of Science Fiction, 302-303.

- ↑ Sometimes the Magic Works, 13.

- ↑ Greg Hildebrandt On The Sword of Shannara - Del Rey - Suvudu

- 1 2 Massengill, David (2001). "18 Seattle books". Seattle Weekly. Retrieved 2008-08-26.

- ↑ Bleiler, Richard (2003). Supernatural Fiction Writers: Contemporary Fantasy and Horror. Charles Scribner's Sons. p. 154.

- 1 2 3 Sometimes the Magic Works, 188.

- ↑ Terry Brooks - Online Radio Interview with the Author - The Author Hour

- 1 2 Sometimes the Magic Works, 190.

- ↑ Young Adult Fantasy Fiction, 81.

- 1 2 Fantasy Literature, 55.

- ↑ Brooks, Terry (2002). "December 2002 Ask Terry Q&A". Retrieved 2008-06-24.

- ↑ Choice (July–August 1977): 30.

- 1 2 quoted from Young Adult Fantasy Fiction, 81.

- 1 2 Carter, Lin (1978). The Year's Best Fantasy Stories: 4. New York: DAW Books. pp. 207–208.

- ↑ Schlobin, Roger (1979). The Literature of Fantasy: A Comprehensive, Annotated Bibliography of Modern Fantasy Fiction. Garland Pub. p. 31. ISBN 0-8240-9757-2.

- ↑ Attebery, Brian (1980). The Fantasy Tradition in American Literature: From Irving to Le Guin. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. p. 155.

- ↑ Card, Orson Scott (1999). "Uncle Orson's Writing Class: On Plagiarism, Borrowing, Resemblance, and Influence". Retrieved 2006-09-08.

- 1 2 3 4 Shippey, Tom (2000). J.R.R. Tolkien: Author of the Century. London: HarperCollins. pp. 2001 paperback, 319–320.

- ↑ Sometimes the Magic Works, 188-190.

- ↑ Wolfe, Gene (2001). "The Best Introduction to the Mountains". Interzone 174 (December 2001). Retrieved 2008-06-28.

- 1 2 3 4 Herbert, Frank (10 April 1977). "Some Author, Some Tolkien". The New York Times Book Review: 15.

- ↑ Batchelor, John Calvin (10 October 1977). "Tolkien Again: Lord Foul and Friends Infest a Morbid but Moneyed Land". The Village Voice. Retrieved 27 December 2009.

- ↑ Kepert, L.V. (28 August 1977). "In the Steps of Tolkien". The Sun-Herald. Retrieved 27 December 2009.

- ↑ Cunningham, J.R. (4 October 1977). "Young Writer has Tolkien Touch". Pittsburgh Press. Retrieved 27 December 2009.

- ↑ Timmerman, John H. (1983). Other Worlds: The Fantasy Genre. Bowling Green: Bowling Green State University Popular Press. p. 116.

- ↑ Barron, Neil; Tymn, Marshall B. (1999). Fantasy and Horror: A Critical and Historical Guide to Literature, Illustration, Film, TV, Radio, and the Internet. Scarecrow Press. p. 360.

- ↑ Winters, Louise J. (1994). Laura Standley Berger, ed. Twentieth-Century Young Adult Writers. Detroit: St. James Press. p. 37.

- ↑ Pringle, David (2006) [1998]. The Ultimate Encyclopedia of Fantasy. London: Carlton. p. 156.

- 1 2 Pringle, David (2006) [1998]. The Ultimate Encyclopedia of Fantasy. London: Carlton. p. 37.

- ↑ Slavicsek, Bill; Baker, Richard; Mohan, Kim (2005). Dungeons & Dragons For Dummies. For Dummies. p. 376. ISBN 0-7645-8459-6.

- ↑ Brooks, Terry (25 November 2009). "2009 Holiday Letter". Terrybrooks.net. Retrieved 27 December 2009.

- ↑ Sneider, Jeff (10 September 2011). "Sonar, Farah to adapt 'Shannara' for TV". Variety. Retrieved 13 January 2013.

Sources

- Brooks, Terry (2003). Sometimes The Magic Works: Lessons from a Writing Life. New York: Ballantine. ISBN 0-345-46551-2. OCLC 54854572.

- del Rey, Lester (1980). The World of Science Fiction: 1926-1976 - The History of a Subculture. New York and London: Garland. ISBN 0-8240-1446-4. OCLC 5500269.

- MacRae, Cathi Dunn (1998). Presenting Young Adult Fantasy Fiction. New York City: Twayne Publishers. ISBN 0-8057-8220-6. OCLC 38478522.

- Tymn, Marshall B; Zahorski, Kenneth J.; Boyer, Robert H. (1979). Fantasy Literature: A Core Collection and Reference Guide. New Providence, New Jersey: R.R. Bowker. ISBN 0-8352-1153-3. OCLC 5051748.

External links

- Author's Note for The Sword of Shannara

- The Sword of Shannara - Chapter One (Official website)

- Artwork for early editions by The Brothers Hildebrandt

- "How Terry Brooks Saved Epic Fantasy", A Dribble of Ink.