Swimmer's itch

| Swimmer's itch | |

|---|---|

| |

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | Infectious disease |

| ICD-10 | B65.3 |

| ICD-9-CM | 120.3 |

| DiseasesDB | 32723 |

Swimmer’s itch, also known as lake itch, duck itch, cercarial dermatitis,[1] and schistosome cercarial dermatitis,[2]:432 is a short-term immune reaction occurring in the skin of humans that have been infected by water-borne schistosomatidae. Symptoms, which include itchy, raised papules, commonly occur within hours of infection and do not generally last more than a week.

A number of different flatworm parasites in the family Schistosomatidae are what cause swimmer’s itch. These parasites use both freshwater snails and vertebrates as hosts in their parasitic life cycles. Mostly waterfowl are used as the vertebrate host. During one of their life stages, the larvae of the parasite, cercariae, leave the water snails and swim freely in the freshwater, attempting to encounter water birds. These larvae can accidentally come into contact with the skin of a swimmer. The cercaria penetrates the skin and dies in the skin immediately. The cercariae cannot infect humans, but they cause an inflammatory immune reaction. This reaction causes initially mildly itchy spots on the skin. Within hours, these spots become raised papules which are intensely itchy. Each papule corresponds to the penetration site of a single parasite.

The schistosomatidae that give rise to swimmer’s itch should not to be confused with those of the genus Schistosoma, which infect humans and cause the serious human disease schistosomiasis, or with larval stages of thimble jellyfish (Linuche unguiculata), which give rise to seabather's eruption. Seabather's eruption mostly occurs in salt water, on skin covered by clothing or hair, whereas swimmer's itch mostly occurs in freshwater, on uncovered skin.[3]

Since it was first described in Michigan in 1928,[4] swimmer's itch has been reported from around the world. Some suggest incidence may be on the rise,[5] although this may also be attributed to better monitoring.

Cause

The schistosomatidae genera most commonly associated with swimmer’s itch in humans are Trichobilharzia and Gigantobilharzia. Trematodes in these groups normally complete their life cycles in water birds. However, swimmer’s itch can also be caused by schistosome parasites of non-avian vertebrates, such as Schistosomatium douthitti, which infects snails and rodents. Other taxa reported to cause the reaction include Bilharziella polonica and Schistosoma bovis. In marine habitats, especially along the coasts, swimmer’s itch can occur as well.[6] In Australia, the so-called "pelican itch" is caused by cercariae of the genus Austrobilharzia employing marine gastropods of the genus Batillaria (B. australis) as intermediate hosts.

Life cycles of non-human schistosomes

The schistosomes use two hosts in their life cycles. One is an aquatic snail, the other is a bird or mammal.

- Schistosomes are gonochoristic and sexual reproduction takes place in the vertebrate host. In genera that infect birds, adult worms occur in tissues and veins of the host’s gastrointestinal tract, where they produce eggs that are shed into water with host feces.

Note: One European species, Trichobilharzia regenti, instead infects the bird host’s nasal tissues and larvae hatch from the eggs directly in the tissue during drinking/feeding of the infected birds.[7]

- Once a schistosome egg is immersed in water, a short-lived, non-feeding, free-living stage known as the miracidium emerges. The miracidium uses cilia to follow chemical and physical cues thought to increase its chances of finding the first intermediate host in its life cycle, an aquatic snail.

- After infecting a snail, it develops into a mother sporocyst, which in turn undergoes asexual reproduction, yielding large numbers of daughter sporocysts, which asexually produce another short-lived, free-living stage, the cercaria.

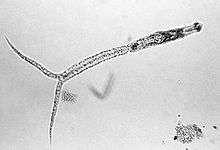

- Cercariae use a tail-like appendage (often forked in genera causing swimmer’s itch) to swim to the surface of the water; and use various physical and chemical cue in order to locate the next and final (definitive) host in the life cycle, a bird.

- After locating a bird, the parasite penetrates through the skin (usually the feet), dropping the forked tail in the process. Inside the circulatory system, the immature worms (schistosomula) develop into mature male and female worms, mate and migrate through the host’s circulatory system (or nervous system in case of T. regenti) to the final location (veins feeding the gastrointestinal tract) within the host body. There they lay eggs in the small veins in the intestinal mucosa from which they make their way into the lumen of the gut, and are dumped into the water when the bird defecates.

- BOURNS, T. K. R., J. C. ELLIS, and M. E. RAU. 1973. Migration and development of Trichobilharzia ocellara (Trematoda: Schistosomatidae) in its duck hosts. Can. J. Zool. 51: 1021-1030

Risk factors

Humans usually become infected with avian schistosomes after swimming in lakes or other bodies of slow-moving fresh water. Some laboratory evidence indicates snails shed cercariae most intensely in the morning and on sunny days, and exposure to water in these conditions may therefore increase risk. Duration of swimming is positively correlated with increased risk of infection in Europe[8] and North America,[9] and shallow inshore waters—snail habitat—undoubtedly harbour higher densities of cercariae than open waters offshore. Onshore winds are thought to cause cercariae to accumulate along shorelines.[10] Studies of infested lakes and outbreaks in Europe and North America have found cases where infection risk appears to be evenly distributed around the margins of water bodies[8] as well as instances where risk increases in endemic swimmer's itch "hotspots".[10] Children may become infected more frequently and more intensely than adults but this probably reflects their tendency to swim for longer periods inshore, where cercariae also concentrate.[11] Stimuli for cercarial penetration into host skin include unsaturated fatty acids, such as linoleic and linolenic acids. These substances occur naturally in human skin and are found in sun lotions and creams based on plant oils.

Control measures and treatment

Various strategies targeting the mollusc and avian hosts of schistosomes, have been used by lakeside residents in recreational areas of North America to deal with outbreaks of swimmer's itch. In Michigan, for decades, authorities used copper sulfate as a molluscicide to reduce snail host populations and thereby the incidence of swimmer's itch. The results with this agent have been inconclusive, possibly because:

- Snails become tolerant

- Local water chemistry reduces the molluscicide's efficacy

- Local currents diffuse it

- Adjacent snail populations repopulate a treated area[12]

More importantly, perhaps, copper sulfate is toxic to more than just molluscs, and the effects of its use on aquatic ecosystems are not well understood.

Another method targeting the snail host, mechanical disturbance of snail habitat, has been also tried in some areas of North America[10] and Lake Annecy in France, with promising results. Some work in Michigan suggests that administering praziquantel to hatchling waterfowl can reduce local swimmer's itch rates in humans.[13] Work on schistosomiasis showed that water-resistant topical applications of the common insect repellent DEET prevented schistosomes from penetrating the skin of mice.[14] Also 0.1-1% niclosamide formulation in water-resistant sun cream or Safe SeaTM cream protecting against jellyfish stings were shown to be highly reliable protectants, having lethal effect on schistosome cercariae.[15] Public education of risk factors, a good alternative to the aforementioned interventionist strategies, can also reduce human exposure to cercariae. Experience at Higgins Lake, Michigan, where systematic research on swimmer's Itch was conducted in the 1990s, shows that periodic brisk toweling of the lower extremities is effective in preventing swimmer's Itch.

Orally administered hydroxyzine, an antihistamine, is sometimes prescribed to treat swimmer's itch and similar dermal allergic reactions. In addition, bathing in an oatmeal, baking soda, or Epsom salts can also provide relief of symptoms.[16]

Other names

Swimmer's itch has various other names. In eastern nations, it is often named in reference to the rice paddies where it is contracted, producing names which translate to "rice paddy itch". For example, in Japan it is called "kubure" or "kobanyo", in Malaysia, "sawah", and in Thailand, "hoi con".

In the United States it is known to some as "duckworms" (in coastal New Jersey), "duck rash" (in the lakes region of New Hampshire) or duck lice, and "clam digger's itch". Also in Western Minnesota, particularly on Lake Minnewaska, it is known as "lake itch".

In certain parts of Canada, mainly Ontario, it is known as "Duck Lice" and "Beaver Lice". In British Columbia and Alberta it is also referred to as "Duck Mites".

In Australia it is known as "pelican itch".

In Switzerland, particularly on Lake Neuchatel (Lac de Neuchâtel, Neuenburgersee), it is known as "pou du canard," (or "dermatite du baigneur").[17]

Similarly in Brazil, the waterbodies in which it is contracted are called lagoas da coceira ("lagoons of the itch"). All medical conditions caused by blood-flukes including swimmer's itch, nevertheless, are called either by the formal ones esquistossomose or bilharzíase, or by the colloquial barriga d'água ("belly [full, composed] of water"). This is not completely due to ignorance, but also by the fact that the only Schistosoma species significantly occurring in Brazil (Schistosoma mansoni) is among the responsibles for human schistosomiasis, so one has to avoid any lagoa de coceira or swimmer's itch with the intent of not getting the disease.

See also

References

- ↑ Rapini, Ronald P.; Bolognia, Jean L.; Jorizzo, Joseph L. (2007). Dermatology: 2-Volume Set. St. Louis: Mosby. ISBN 1-4160-2999-0.

- ↑ James, William D.; Berger, Timothy G.; et al. (2006). Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: clinical Dermatology. Saunders Elsevier. ISBN 0-7216-2921-0.

- ↑ Osment, Ls (Oct 1976). "Update: seabather's eruption and swimmer's itch.". Cutis; cutaneous medicine for the practitioner 18 (4): 545–7. ISSN 0011-4162. PMID 1017216.

- ↑ Cort WW (1928). "Schistosome dermatitis in the United States (Michigan).". JAMA 90: 1027–9. doi:10.1001/jama.1928.02690400023010.

- ↑ Hjorngaard Larsen A, Bresciani J, Buchmann K (2004). "Increasing frequency of cercarial dermatitis at higher latitudes". Acta Parasitologica 49 (3): 217–21.

- ↑ Brant S, Cohen A, James D, Hui L, Hom A, Loker E (2010). "Cercarial Dermatitis Transmitted by Exotic Marine Snail". Emerging Infectious Diseases 16 (9): 1357–65. doi:10.3201/eid1609.091664. PMC 3294964. PMID 20735918.

- ↑ Horák, P., Kolářová, L. & Dvořák, J. 1998: Trichobilharzia regenti n. sp. (Schistosomatidae, Bilharziellinae), a new nasal schistosome from Europe. Parasite, 5, 349-357. doi:10.1051/parasite/1998054349 PubMed (Free PDF)

- 1 2 Chamot E, Toscani L, Rougemont A (1998). "Public health importance and risk factors for cercarial dermatitis associated with swimming in Lake Leman at Geneva, Switzerland". Epidemiol. Infect. 120 (3): 305–14. doi:10.1017/S0950268898008826. PMC 2809408. PMID 9692609.

- ↑ Lindblade KA (1998). "The epidemiology of cercarial dermatitis and its association with limnological characteristics of a northern Michigan lake". J. Parasitol. 84 (1): 19–23. doi:10.2307/3284521. JSTOR 3284521. PMID 9488332.

- 1 2 3 Leighton BJ, Zervos S, Webster JM (2000). "Ecological factors in schistosome transmission, and an environmentally benign method for controlling snails in a recreational lake with a record of schistosome dermatitis". Parasitol. Int. 49 (1): 9–17. doi:10.1016/S1383-5769(99)00034-3. PMID 10729712.

- ↑ Verbrugge LM, Rainey JJ, Reimink RL, Blankespoor HD (2004). "Prospective study of swimmer's itch incidence and severity". J. Parasitol. 90 (4): 697–704. doi:10.1645/GE-237R. PMID 15357056.

- ↑ Blankespoor, H. D., Reimink, R. L. (1991). "The control of swimmer's itch in Michigan: Past, present, and future". Michigan Academician 24 (1): 7–23.

- ↑ Blankespoor, C. L., Reimink, R. L., Blankespoort, H. D. (2001). "Efficacy of praziquantel in treating natural schistosome infections in common mergansers". Journal of Parasitology 87 (2): 424–6. doi:10.1645/0022-3395(2001)087[0424:EOPITN]2.0.CO;2. PMID 11318576.

- ↑ Salafsky, B., Ramaswamy, K., He, Y. X., Li, J., Shibuya, T. (November 1999). "Development and evaluation of LIPODEET, a new long-acting formulation of N, N-diethyl-m-toluamide (DEET) for the prevention of schistosomiasis". Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 61 (5): 743–50. PMID 10586906.

- ↑ Wulff, C,. Haeberlein, S., Haas, W. (2007). "Cream formulations protecting against cercarial dermatitis by Trichobilharzia". Parasitol. Res. 101 (1): 91–7. doi:10.1007/s00436-006-0431-5. PMID 17252275.

- ↑ In CDC. "Swimmers Itch FAQS." retrieved May 12, 2014

- ↑ http://www.ne.ch/neat/site/jsp/rubrique/rubrique.jsp?DocId=10297

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Schistosome cercarial dermatitis. |

- Information portal for NSF funded research on avian schistosome diversity

- CDC

- CDC

- DermNet arthropods/swimmers-itch

- Links to pictures of swimmer's itch (Hardin MD/Univ of Iowa)

- Schistosome Group Prague, a member of the European Cercarial Dermatitis Network (ECDEN)

- Swimmer's Itch

- Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, With warm weather, Swimmers Itch makes annual appearance