Sweat therapy

Sweat therapy is the combination of group counseling/psychotherapy with group sweating. Group sweating is social interaction while experiencing psychophysiological responses to heat exposure. Group sweating has strong cultural validity as it has existed throughout the world for thousands of years to promote well-being. Examples include the Finnish Sauna, the Russian Banya (sauna), the American Indian Sweat lodge Ceremony, the Islamic Hammam, the Japanese Mushi-Buro or Sentō, and the African Sifutu. [1]

Group sweating has been used for various physical and mental purposes for thousands of years.[2][3] It has been asserted that the potential health benefits of regular participation in Native American sweat lodges are numerous, but that there is a scarcity of research about the practice.[3] One study involving 24 college students reported that "sweat therapy participants reported more therapeutic factors having an impact on their group counseling experience, rated sessions as more beneficial, and interacted with stronger group cohesion than non-sweat therapy participants." [4]

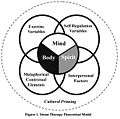

Sweat Therapy Theoretical Model

Colmant and Eason (2009) introduced a theoretical model to describe how sweat rituals operate to deliver positive effects to mind, body and spirit. The theoretical model proposes five factors that reciprocally interact to produce the positive effects of sweat rituals: cultural priming, exercise, self-regulation, metaphorical contextual elements, and interpersonal factors.[5]

Cultural Priming. Different forms of indigenous sweat practices have been found across many geographically and culturally distinct regions of the world: American Indian Sweat Lodge; Finnish Sauna; Greek Sweat Bath; Irish Sweat House; Japanese Mushi-Buro and Korean Jim Jil Bang Jewish Shvitz; Islamic Hammam; Mayan Sweat House; Mexican and Central American Temescal and Inipi; Roman Balnea and Thermae; Russian Bania; Scythian Sweatbath, and South African Sifutu. While there are variations in the different forms of sweat rituals, the common purposes include promoting physical and mental health, spirituality, and socialization. Because sweat rituals have existed for thousands of years throughout the world, the authors suggest that people will be attracted to it and are primed to receive benefits from it that are consistent with their cultural background. The authors hold that the more prominent the practice exists in the individual’s background, the stronger the priming.

Exercise. From the authors' clinical experiences, sweating induces commonly observed effects of exercise on mental health. Sweat practices are similar to exercise as they cause the stimulation of the sympathetic nervous system, activation of the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal hormonal axis, and an increase in noradrenaline. The sweating experience appears to produce profound physiological changes and perceptions of physical symptoms. Unlike typical forms of exercise, sweat practices cause an increase in B-endorphins and do not increase the concentration of adrenaline in the blood stream. Sweat practices also contrast with the majority of exercise activities because they do not require muscle tension, the movement of large muscle groups, and attentional capacities to be focused on muscle coordination. Sweat practices are a unique form of exercise as they cause muscle relaxation and allow focal attention to be placed on another activity, such as group content and process.

Self-Regulation. Self-regulation is the activity of setting, working toward and achieving goals related to one’s personal desires. Sweat rituals seem to promote self-regulation by helping one gain insight through introspection, mark a commitment to personal goals, improve frustration tolerance and maintain balance and harmony. The authors propose that participants in sweat practices respond to the intense heat exposure using a meditative attentiveness characterized by a dynamic balance between alertness and relaxation, which promotes insight and adaptive coping . The authors describe the heat during sweat therapy as a dynamic force.

At first, the heat is soothing and as the body begins to respond to the heat through sweating, the body’s muscles experience a release of tension, promoting a deeper state of relaxation. However, rather than slipping into a state of relaxation resembling rest or sleep, further heat exposure keeps the mind and body active. As the heat becomes more intense, the participant is challenged to keep the mind relaxed, requiring meditative attentiveness. As the experience moves from relaxation to endurance, it seems that participants are faced with a choice. One can either allow negative thoughts and feelings related to the heat to become the focus of their experience or one can focus on thoughts and feelings that help one to adapt, cope, and thrive when faced with adversity. This meditative attentiveness and sense of positive adaptation seem to encourage problem solving and further build on the state of cognitive arousal produced by sweating as a form of exercise.

Metaphorical Contextual Elements. Sweat practices are more than just intense exposure to heat. Intense heat exposure unchecked can result in heat disorders such as heat stroke, heat exhaustion, and heat collapse. Sweat practices developed over centuries through human intelligence, creativity, and wisdom use intense heat exposure to promote physical and mental health, spirituality, and socialization. The metaphorical contextual elements of sweat practices are a main contributing factor to the positive effects of the experience. Many of the contextual elements common to sweat practices include taking breaks, dimmed lighting, wearing sparse or no clothing, drinking large quantities of water, and the symbolism of fire. The authors hold that these contextual elements are important to facilitating biopsychosocial benefits from sweat practices and promote metaphorical meaning complementary to the other factors in the Sweat Therapy Theoretical Model. Much of the metaphorical transfer of meaning occurs through the use of rituals. For example, the sweating experience provides an ordeal that one submits to. Change is symbolically represented by basic elements (earth, air, fire, water) changing forms. Fire burns wood turning to smoke. Rocks glow red with heat. Water thrown on super-heated rocks changes to steam and intense heat. One withstands the heat as proof of fitness and commitment. The experience is a lesson in humility as the intensity grows. Just at the point of feeling wiped out, the person emerges from the sweat. . . they begin to recuperate and drink wholesome life-giving water. Then comes the feeling of strength and rejuvenation. The invigorating ritual brings the participant to life again. Through submission and ordeal one becomes wiser and learns a lesson in humility by experiencing a rite of death and rebirth that marks the passage to a higher level of maturity.

Interpersonal Factors. Sweating and interpersonal interaction seem to be natural catalysts for one another. As previously stated, exercise, self-regulation, metaphorical contextual elements, and interpersonal factors in the Sweat Therapy Theoretical Model interact in a reciprocal manner. When focusing on interpersonal factors, the authors hold that exercise, metaphor, and self-regulation seem to intensify group dynamics. The sweating experience promotes relaxation, stress relief and self-disclosure. At the same time, group interaction provides an opportunity for participants to process the experience. From the authors clinical experience with sweat therapy, group members seem to perceive the sweating experience as a moderate challenge to which they respond by seeking social support and engaging in thinking that promotes self-esteem, such as “Although I’m uncomfortably hot, I am staying in the sauna because doing so will make me better in some way.” The sweat group condition seems to prompt altruism that quickly translates into cohesion. The authors have observed group members working together as a unit to get through the challenge by offering towels and water to one another and showing frequent concern for one another's ability to handle the heat. These seemingly simple expressions of sharing and concern for one another become part of the group norms and transcend into people showing greater care and concern for one another.

References

- ↑ PsychSymposium

- ↑ "Calculating the Cultural Validity of Group Sweating." PsychSymposium.com. Retrieved June 10, 2006.

- 1 2 Berger LR, Rounds JE. "Sweat Lodges: A medical view." The IHS Primary Care Provider. Volume 23, Number 6, June 1998, pp. 69-75.

- ↑ Colmant S, Eason, E, Winterowd C, Jacobs Sue, Cashel Chris. "Investigating the Effects of Sweat Therapy on Group Dynamics and Affect." Journal for Specialists in Group Work, Volume 30, Number 4, December 2005, pp. 329-341(13).

- ↑ Eason, Colmant, Winterowd. (2009). Journal of Experiential Education, Volume 32, No. 2 pp. 121-136