Surface finish

Surface finish, also known a surface texture or surface topography, is the nature of a surface as defined by the 3 characteristics of lay, surface roughness, and waviness.[1] It comprises the small local deviations of a surface from the perfectly flat ideal (a true plane).

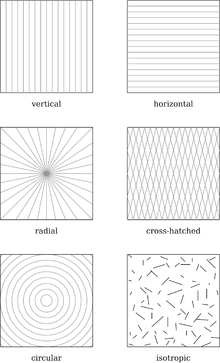

Surface texture is one of the important factors that control friction and transfer layer formation during sliding.[2] Considerable efforts have been made to study the influence of surface texture on friction and wear during sliding conditions.[3][4] Surface textures can be isotropic or anisotropic.[2][5] Sometimes, stick-slip friction phenomena can be observed during sliding depending on surface texture.[6][7][8]

Each manufacturing process (such as the many kinds of machining) produces a surface texture. The process is usually optimized to ensure that the resulting texture is usable. If necessary, an additional process will be added to modify the initial texture. The latter process may be grinding (abrasive cutting), polishing, lapping, abrasive blasting, honing, electrical discharge machining (EDM), milling, lithography, industrial etching/chemical milling, laser texturing, or other processes.[9][10]

Lay

Lay is the direction of the predominant surface pattern ordinarily determined by the production method used.

Surface roughness

Surface roughness commonly shortened to roughness, is a measure of the finely spaced surface irregularities.[1] In engineering, this is what is usually meant by "surface finish".

Waviness

Waviness is the measure of surface irregularities with a spacing greater than that of surface roughness. These usually occur due to warping, vibrations, or deflection during machining.[1]

Measurement

Surface finish may be measured in two ways: contact and non-contact methods. Contact methods involve dragging a measurement stylus across the surface; these instruments are called profilometers. Non-contact methods include: interferometry, confocal microscopy, focus variation, structured light, electrical capacitance, electron microscopy, and photogrammetry.

The most common method is to use a diamond stylus profilometer. The stylus is run perpendicular to the lay of the surface.[1] The probe usually traces along a straight line on a flat surface or in a circular arc around a cylindrical surface. The length of the path that it traces is called the measurement length. The wavelength of the lowest frequency filter that will be used to analyze the data is usually defined as the sampling length. Most standards recommend that the measurement length should be at least seven times longer than the sampling length, and according to the Nyquist–Shannon sampling theorem it should be at least two times longer than the wavelength of interesting features. The assessment length or evaluation length is the length of data that will be used for analysis. Commonly one sampling length is discarded from each end of the measurement length. 3D measurements can be made with a profilometer by scanning over a 2D area on the surface.

The disadvantage of a profilometer is that it is not accurate when the size of the features of the surface are close to the same size as the stylus. Another disadvantage is that profilometers have difficulty detecting flaws of the same general size as the roughness of the surface.[11] There are also limitations for non-contact instruments. For example, instruments that rely on optical interference cannot resolve features that are less than some fraction of the operating wavelength. This limitation can make it difficult to accurately measure roughness even on common objects, since the interesting features may be well below the wavelength of light. The wavelength of red light is about 650 nm,[12] while the average roughness, (Ra) of a ground shaft might be 2000 nm.

The first step of analysis is to filter the raw data to remove very high frequency data (called "micro-roughness") since it can often be attributed to vibrations or debris on the surface. Filtering out the micro-roughness at a given cut-off threshold also allows to bring closer the roughness assessment made using profilometers having different stylus ball radius e.g. 2µm and 5µm radii. Next, the data is separated into roughness, waviness and form. This can be accomplished using reference lines, envelope methods, digital filters, fractals or other techniques. Finally, the data is summarized using one or more roughness parameters, or a graph. In the past, surface finish was usually analyzed by hand. The roughness trace would be plotted on graph paper, and an experienced machinist decided what data to ignore and where to place the mean line. Today, the measured data is stored on a computer, and analyzed using methods from signal analysis and statistics.[13]

-

The effect of different form removal techniques on surface finish analysis

-

Plots showing how filter cutoff frequency affects the separation between waviness and roughness

-

Illustration showing how the raw profile from a surface finish trace is decomposed into a primary profile, form, waviness and roughness

-

Illustration showing the effect of using different filters to separate a surface finish trace into waviness and roughness

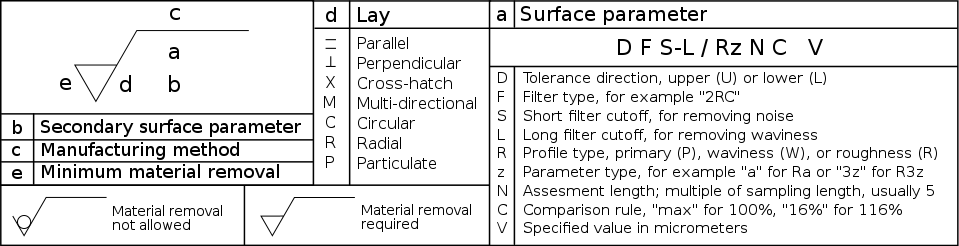

Specification

In the United States, surface finish is usually specified using the ASME Y14.36M standard. The other common standard is International Organization for Standardization (ISO) 1302.

Manufacturing

Many factors contribute to the surface finish in manufacturing. In forming processes, such as molding or metal forming, surface finish of the die determines the surface finish of the workpiece. In machining the interaction of the cutting edges and the microstructure of the material being cut both contribute to the final surface finish.

In general, the cost of manufacturing a surface increases as the surface finish improves.[14] Any given manufacturing process is usually optimized enough to ensure that the resulting texture is usable for the part's intended application. If necessary, an additional process will be added to modify the initial texture. The expense of this additional process must be justified by adding value in some way—principally better function or longer lifespan. Parts that have sliding contact with others may work better or last longer if the roughness is lower. Aesthetic improvement may add value if it improves the saleability of the product.

A practical example is as follows. An aircraft maker contracts with a vendor to make parts. A certain grade of steel is specified for the part because it is strong enough and hard enough for the part's function. The steel is machinable although not free-machining. The vendor decides to mill the parts. The milling can achieve the specified roughness (for example, ≤ 3.2 µm) as long as the machinist uses premium-quality inserts in the end mill and replaces the inserts after every 20 parts (as opposed to cutting hundreds before changing the inserts). There is no need to add a second operation (such as grinding or polishing) after the milling as long as the milling is done well enough (correct inserts, frequent-enough insert changes, and clean coolant). The inserts and coolant cost money, but the costs that grinding or polishing would incur (more time and additional materials) would cost even more than that. Obviating the second operation results in a lower unit cost and thus a lower price. The competition between vendors elevates such details from minor to crucial importance. It was certainly possible to make the parts in a slightly less efficient way (two operations) for a slightly higher price; but only one vendor can get the contract, so the slight difference in efficiency is magnified by competition into the great difference between the prospering and shuttering of firms.

Just as different manufacturing processes produce parts at various tolerances, they are also capable of different roughnesses. Generally these two characteristics are linked: manufacturing processes that are dimensionally precise create surfaces with low roughness. In other words, if a process can manufacture parts to a narrow dimensional tolerance, the parts will not be very rough.

Due to the abstractness of surface finish parameters, engineers usually use a tool that has a variety of surface roughnesses created using different manufacturing methods.[14]

References

- 1 2 3 4 Degarmo, Black & Kohser 2003, p. 223.

- 1 2 Pradeep L. Menezes, Kishore and Satish V. Kailas, Studies on friction and transfer layer using inclined scratch, Tribology International, 39(2), 2006, 175–183.

- ↑ Pradeep L. Menezes, Kishore, Shimjith M. and Satish V. Kailas, Influence of surface texture on friction and transfer layer formation in Mg-8Al alloy/steel tribo-system, Indian Journal of Tribology, 2(1), 2007, 46-54.

- ↑ Pradeep L. Menezes, Kishore and Satish V. Kailas, On the effect of surface texture on friction and transfer layer formation – A study using Al and steel pair, Wear, 265(11-12), 2008, 1655-1669.

- ↑ Pradeep L. Menezes, Kishore and Satish V. Kailas, Effect of roughness parameter and grinding angle on coefficient of friction when sliding of Al-Mg alloy over EN8 steel, ASME: Journal of Tribology, 128(4), 2006, 697-704.

- ↑ Pradeep L. Menezes, Kishore and Satish V. Kailas, Influence of surface texture on coefficient of friction and transfer layer formation during sliding of pure magnesium pin on 080 M40 (EN8) steel plate, Wear, 261(5-6), 2006, 578-591.

- ↑ Pradeep L. Menezes, Kishore and Satish V. Kailas, Effect of directionality of unidirectional grinding marks on friction and transfer layer formation of Mg on steel using inclined scratch test, Materials Science and Engineering A, 429(1-2), 2006, 149-160.

- ↑ Menezes PL, Kishore, Kailas SV. Studies on friction and transfer layer: Role of surface texture, Tribology Letters, 24(3), 2006, 265-273.

- ↑ Pradeep L. Menezes, Kishore and Satish V. Kailas, Effect of surface roughness parameters and surface texture on friction and transfer layer formation in tin-steel tribo-system, Journal of Materials Processing Technology, 208(1-3), 2008, 372-382.

- ↑ Pradeep L. Menezes, Kishore and Satish V. Kailas, Role of surface texture and roughness parameters in friction and transfer layer formation under dry and lubricated sliding conditions, International Journal of Materials Research, 99(7), 2008, 795-807.

- ↑ Degarmo, Black & Kohser 2003, p. 224.

- ↑ "What Wavelength Goes With a Color?". Retrieved 2008-05-14.

- ↑ Whitehouse, DJ. (1994). Handbook of Surface Metrology, Bristol: Institute of Physics Publishing. ISBN 0-7503-0039-6

- 1 2 Degarmo, Black & Kohser 2003, p. 227.

Bibliography

- Degarmo, E. Paul; Black, J T.; Kohser, Ronald A. (2003), Materials and Processes in Manufacturing (9th ed.), Wiley, ISBN 0-471-65653-4.

Further reading

- Marks' Standard Handbook for Mechanical Engineers, Section 13.5 "Surface Texture Designation, Production, and Control" by Thomas W. Wolf.