Supervised learning

| Machine learning and data mining |

|---|

|

| Problems |

| Clustering |

| Dimensionality reduction |

| Structured prediction |

| Anomaly detection |

| Neural nets |

| Theory |

| Machine learning venues |

| Data mining venues |

|

|

Supervised learning is the machine learning task of inferring a function from labeled training data.[1] The training data consist of a set of training examples. In supervised learning, each example is a pair consisting of an input object (typically a vector) and a desired output value (also called the supervisory signal). A supervised learning algorithm analyzes the training data and produces an inferred function, which can be used for mapping new examples. An optimal scenario will allow for the algorithm to correctly determine the class labels for unseen instances. This requires the learning algorithm to generalize from the training data to unseen situations in a "reasonable" way (see inductive bias).

The parallel task in human and animal psychology is often referred to as concept learning.

Overview

In order to solve a given problem of supervised learning, one has to perform the following steps:

- Determine the type of training examples. Before doing anything else, the user should decide what kind of data is to be used as a training set. In the case of handwriting analysis, for example, this might be a single handwritten character, an entire handwritten word, or an entire line of handwriting.

- Gather a training set. The training set needs to be representative of the real-world use of the function. Thus, a set of input objects is gathered and corresponding outputs are also gathered, either from human experts or from measurements.

- Determine the input feature representation of the learned function. The accuracy of the learned function depends strongly on how the input object is represented. Typically, the input object is transformed into a feature vector, which contains a number of features that are descriptive of the object. The number of features should not be too large, because of the curse of dimensionality; but should contain enough information to accurately predict the output.

- Determine the structure of the learned function and corresponding learning algorithm. For example, the engineer may choose to use support vector machines or decision trees.

- Complete the design. Run the learning algorithm on the gathered training set. Some supervised learning algorithms require the user to determine certain control parameters. These parameters may be adjusted by optimizing performance on a subset (called a validation set) of the training set, or via cross-validation.

- Evaluate the accuracy of the learned function. After parameter adjustment and learning, the performance of the resulting function should be measured on a test set that is separate from the training set.

A wide range of supervised learning algorithms is available, each with its strengths and weaknesses. There is no single learning algorithm that works best on all supervised learning problems (see the No free lunch theorem).

There are four major issues to consider in supervised learning:

Bias-variance tradeoff

A first issue is the tradeoff between bias and variance.[2] Imagine that we have available several different, but equally good, training data sets. A learning algorithm is biased for a particular input  if, when trained on each of these data sets, it is systematically incorrect when predicting the correct output for

if, when trained on each of these data sets, it is systematically incorrect when predicting the correct output for  . A learning algorithm has high variance for a particular input

. A learning algorithm has high variance for a particular input  if it predicts different output values when trained on different training sets. The prediction error of a learned classifier is related to the sum of the bias and the variance of the learning algorithm.[3] Generally, there is a tradeoff between bias and variance. A learning algorithm with low bias must be "flexible" so that it can fit the data well. But if the learning algorithm is too flexible, it will fit each training data set differently, and hence have high variance. A key aspect of many supervised learning methods is that they are able to adjust this tradeoff between bias and variance (either automatically or by providing a bias/variance parameter that the user can adjust).

if it predicts different output values when trained on different training sets. The prediction error of a learned classifier is related to the sum of the bias and the variance of the learning algorithm.[3] Generally, there is a tradeoff between bias and variance. A learning algorithm with low bias must be "flexible" so that it can fit the data well. But if the learning algorithm is too flexible, it will fit each training data set differently, and hence have high variance. A key aspect of many supervised learning methods is that they are able to adjust this tradeoff between bias and variance (either automatically or by providing a bias/variance parameter that the user can adjust).

Function complexity and amount of training data

The second issue is the amount of training data available relative to the complexity of the "true" function (classifier or regression function). If the true function is simple, then an "inflexible" learning algorithm with high bias and low variance will be able to learn it from a small amount of data. But if the true function is highly complex (e.g., because it involves complex interactions among many different input features and behaves differently in different parts of the input space), then the function will only be learnable from a very large amount of training data and using a "flexible" learning algorithm with low bias and high variance. Good learning algorithms therefore automatically adjust the bias/variance tradeoff based on the amount of data available and the apparent complexity of the function to be learned.

Dimensionality of the input space

A third issue is the dimensionality of the input space. If the input feature vectors have very high dimension, the learning problem can be difficult even if the true function only depends on a small number of those features. This is because the many "extra" dimensions can confuse the learning algorithm and cause it to have high variance. Hence, high input dimensionality typically requires tuning the classifier to have low variance and high bias. In practice, if the engineer can manually remove irrelevant features from the input data, this is likely to improve the accuracy of the learned function. In addition, there are many algorithms for feature selection that seek to identify the relevant features and discard the irrelevant ones. This is an instance of the more general strategy of dimensionality reduction, which seeks to map the input data into a lower-dimensional space prior to running the supervised learning algorithm.

Noise in the output values

A fourth issue is the degree of noise in the desired output values (the supervisory target variables). If the desired output values are often incorrect (because of human error or sensor errors), then the learning algorithm should not attempt to find a function that exactly matches the training examples. Attempting to fit the data too carefully leads to overfitting. You can overfit even when there are no measurement errors (stochastic noise) if the function you are trying to learn is too complex for your learning model. In such a situation that part of the target function that cannot be modeled "corrupts" your training data - this phenomenon has been called deterministic noise. When either type of noise is present, it is better to go with a higher bias, lower variance estimator.

In practice, there are several approaches to alleviate noise in the output values such as early stopping to prevent overfitting as well as detecting and removing the noisy training examples prior to training the supervised learning algorithm. There are several algorithms that identify noisy training examples and removing the suspected noisy training examples prior to training has decreased generalization error with statistical significance.[4][5]

Other factors to consider

Other factors to consider when choosing and applying a learning algorithm include the following:

- Heterogeneity of the data. If the feature vectors include features of many different kinds (discrete, discrete ordered, counts, continuous values), some algorithms are easier to apply than others. Many algorithms, including Support Vector Machines, linear regression, logistic regression, neural networks, and nearest neighbor methods, require that the input features be numerical and scaled to similar ranges (e.g., to the [-1,1] interval). Methods that employ a distance function, such as nearest neighbor methods and support vector machines with Gaussian kernels, are particularly sensitive to this. An advantage of decision trees is that they easily handle heterogeneous data.

- Redundancy in the data. If the input features contain redundant information (e.g., highly correlated features), some learning algorithms (e.g., linear regression, logistic regression, and distance based methods) will perform poorly because of numerical instabilities. These problems can often be solved by imposing some form of regularization.

- Presence of interactions and non-linearities. If each of the features makes an independent contribution to the output, then algorithms based on linear functions (e.g., linear regression, logistic regression, Support Vector Machines, naive Bayes) and distance functions (e.g., nearest neighbor methods, support vector machines with Gaussian kernels) generally perform well. However, if there are complex interactions among features, then algorithms such as decision trees and neural networks work better, because they are specifically designed to discover these interactions. Linear methods can also be applied, but the engineer must manually specify the interactions when using them.

When considering a new application, the engineer can compare multiple learning algorithms and experimentally determine which one works best on the problem at hand (see cross validation). Tuning the performance of a learning algorithm can be very time-consuming. Given fixed resources, it is often better to spend more time collecting additional training data and more informative features than it is to spend extra time tuning the learning algorithms.

The most widely used learning algorithms are Support Vector Machines, linear regression, logistic regression, naive Bayes, linear discriminant analysis, decision trees, k-nearest neighbor algorithm, and Neural Networks (Multilayer perceptron).

How supervised learning algorithms work

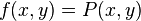

Given a set of  training examples of the form

training examples of the form  such that

such that  is the feature vector of the i-th example and

is the feature vector of the i-th example and  is its label (i.e., class), a learning algorithm seeks a function

is its label (i.e., class), a learning algorithm seeks a function  , where

, where  is the input space and

is the input space and

is the output space. The function

is the output space. The function  is an element of some space of possible functions

is an element of some space of possible functions  , usually called the hypothesis space. It is sometimes convenient to

represent

, usually called the hypothesis space. It is sometimes convenient to

represent  using a scoring function

using a scoring function  such that

such that  is defined as returning the

is defined as returning the  value that gives the highest score:

value that gives the highest score:  . Let

. Let  denote the space of scoring functions.

denote the space of scoring functions.

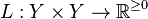

Although  and

and  can be any space of functions, many learning algorithms are probabilistic models where

can be any space of functions, many learning algorithms are probabilistic models where  takes the form of a conditional probability model

takes the form of a conditional probability model  , or

, or  takes the form of a joint probability model

takes the form of a joint probability model  . For example, naive Bayes and linear discriminant analysis are joint probability models, whereas logistic regression is a conditional probability model.

. For example, naive Bayes and linear discriminant analysis are joint probability models, whereas logistic regression is a conditional probability model.

There are two basic approaches to choosing  or

or  : empirical risk minimization and structural risk minimization.[6] Empirical risk minimization seeks the function that best fits the training data. Structural risk minimize includes a penalty function that controls the bias/variance tradeoff.

: empirical risk minimization and structural risk minimization.[6] Empirical risk minimization seeks the function that best fits the training data. Structural risk minimize includes a penalty function that controls the bias/variance tradeoff.

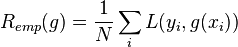

In both cases, it is assumed that the training set consists of a sample of independent and identically distributed pairs,  . In order to measure how well a function fits the training data, a loss function

. In order to measure how well a function fits the training data, a loss function  is defined. For training example

is defined. For training example  , the loss of predicting the value

, the loss of predicting the value  is

is  .

.

The risk  of function

of function  is defined as the expected loss of

is defined as the expected loss of  . This can be estimated from the training data as

. This can be estimated from the training data as

.

.

Empirical risk minimization

In empirical risk minimization, the supervised learning algorithm seeks the function  that minimizes

that minimizes  . Hence, a supervised learning algorithm can be constructed by applying an optimization algorithm to find

. Hence, a supervised learning algorithm can be constructed by applying an optimization algorithm to find  .

.

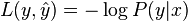

When  is a conditional probability distribution

is a conditional probability distribution  and the loss function is the negative log likelihood:

and the loss function is the negative log likelihood:  , then empirical risk minimization is equivalent to maximum likelihood estimation.

, then empirical risk minimization is equivalent to maximum likelihood estimation.

When  contains many candidate functions or the training set is not sufficiently large, empirical risk minimization leads to high variance and poor generalization. The learning algorithm is able

to memorize the training examples without generalizing well. This is called overfitting.

contains many candidate functions or the training set is not sufficiently large, empirical risk minimization leads to high variance and poor generalization. The learning algorithm is able

to memorize the training examples without generalizing well. This is called overfitting.

Structural risk minimization

Structural risk minimization seeks to prevent overfitting by incorporating a regularization penalty into the optimization. The regularization penalty can be viewed as implementing a form of Occam's razor that prefers simpler functions over more complex ones.

A wide variety of penalties have been employed that correspond to different definitions of complexity. For example, consider the case where the function  is a linear function of the form

is a linear function of the form

.

.

A popular regularization penalty is  , which is the squared Euclidean norm of the weights, also known as the

, which is the squared Euclidean norm of the weights, also known as the  norm. Other norms include the

norm. Other norms include the  norm,

norm,  , and the

, and the  norm, which is the number of non-zero

norm, which is the number of non-zero  s. The penalty will be denoted by

s. The penalty will be denoted by  .

.

The supervised learning optimization problem is to find the function  that minimizes

that minimizes

The parameter  controls the bias-variance tradeoff. When

controls the bias-variance tradeoff. When  , this gives empirical risk minimization with low bias and high variance. When

, this gives empirical risk minimization with low bias and high variance. When  is large, the learning algorithm will have high bias and low variance. The value of

is large, the learning algorithm will have high bias and low variance. The value of  can be chosen empirically via cross validation.

can be chosen empirically via cross validation.

The complexity penalty has a Bayesian interpretation as the negative log prior probability of  ,

,  , in which case

, in which case  is the posterior probabability of

is the posterior probabability of  .

.

Generative training

The training methods described above are discriminative training methods, because they seek to find a function  that discriminates well between the different output values (see discriminative model). For the special case where

that discriminates well between the different output values (see discriminative model). For the special case where  is a joint probability distribution and the loss function is the negative log likelihood

is a joint probability distribution and the loss function is the negative log likelihood  a risk minimization algorithm is said to perform generative training, because

a risk minimization algorithm is said to perform generative training, because  can be regarded as a generative model that explains how the data were generated. Generative training algorithms are often simpler and more computationally efficient than discriminative training algorithms. In some cases, the solution can be computed in closed form as in naive Bayes and linear discriminant analysis.

can be regarded as a generative model that explains how the data were generated. Generative training algorithms are often simpler and more computationally efficient than discriminative training algorithms. In some cases, the solution can be computed in closed form as in naive Bayes and linear discriminant analysis.

Generalizations of supervised learning

There are several ways in which the standard supervised learning problem can be generalized:

- Semi-supervised learning: In this setting, the desired output values are provided only for a subset of the training data. The remaining data is unlabeled.

- Active learning: Instead of assuming that all of the training examples are given at the start, active learning algorithms interactively collect new examples, typically by making queries to a human user. Often, the queries are based on unlabeled data, which is a scenario that combines semi-supervised learning with active learning.

- Structured prediction: When the desired output value is a complex object, such as a parse tree or a labeled graph, then standard methods must be extended.

- Learning to rank: When the input is a set of objects and the desired output is a ranking of those objects, then again the standard methods must be extended.

Approaches and algorithms

- Analytical learning

- Artificial neural network

- Backpropagation

- Boosting (meta-algorithm)

- Bayesian statistics

- Case-based reasoning

- Decision tree learning

- Inductive logic programming

- Gaussian process regression

- Group method of data handling

- Kernel estimators

- Learning Automata

- Minimum message length (decision trees, decision graphs, etc.)

- Multilinear subspace learning

- Naive bayes classifier

- Nearest Neighbor Algorithm

- Probably approximately correct learning (PAC) learning

- Ripple down rules, a knowledge acquisition methodology

- Symbolic machine learning algorithms

- Subsymbolic machine learning algorithms

- Support vector machines

- Minimum Complexity Machines (MCM)

- Random Forests

- Ensembles of Classifiers

- Ordinal classification

- Data Pre-processing

- Handling imbalanced datasets

- Statistical relational learning

- Proaftn, a multicriteria classification algorithm

Applications

- Bioinformatics

- Cheminformatics

- Database marketing

- Handwriting recognition

- Information retrieval

- Object recognition in computer vision

- Optical character recognition

- Spam detection

- Pattern recognition

- Speech recognition

- Supervised learning is a special case of Downward causation in biological systems

General issues

- Computational learning theory

- Inductive bias

- Overfitting (machine learning)

- (Uncalibrated) Class membership probabilities

- Unsupervised_learning

- Version spaces

References

- ↑ Mehryar Mohri, Afshin Rostamizadeh, Ameet Talwalkar (2012) Foundations of Machine Learning, The MIT Press ISBN 9780262018258.

- ↑ S. Geman, E. Bienenstock, and R. Doursat (1992). Neural networks and the bias/variance dilemma. Neural Computation 4, 1–58.

- ↑ G. James (2003) Variance and Bias for General Loss Functions, Machine Learning 51, 115-135. (http://www-bcf.usc.edu/~gareth/research/bv.pdf)

- ↑ C.E. Brodely and M.A. Friedl (1999). Identifying and Eliminating Mislabeled Training Instances, Journal of Artificial Intelligence Research 11, 131-167. (http://jair.org/media/606/live-606-1803-jair.pdf)

- ↑ M.R. Smith and T. Martinez (2011). "Improving Classification Accuracy by Identifying and Removing Instances that Should Be Misclassified". Proceedings of International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN 2011). pp. 2690–2697.

- ↑ Vapnik, V. N. The Nature of Statistical Learning Theory (2nd Ed.), Springer Verlag, 2000.