Superluminal motion

In astronomy, superluminal motion is the apparently faster-than-light motion seen in some radio galaxies, BL Lac objects, quasars and recently also in some galactic sources called microquasars. All of these sources are thought to contain a black hole, responsible for the ejection of mass at high velocities.

When first observed in the early 1970s, superluminal motion was taken to be a piece of evidence against quasars having cosmological distances. Although a few astrophysicists still argue in favor of this view, most believe that apparent velocities greater than the velocity of light are optical illusions and involve no physics incompatible with the theory of special relativity.

Explanation

This phenomenon is caused because the jets are travelling very near the speed of light at a very small angle towards the observer. Because at every point of their path the high-velocity jets are emitting light, the light they emit does not approach the observer much more quickly than the jet itself. This causes the light emitted over hundreds of years of the jet's travel to not have hundreds of light-years of distance between its front end (the earliest light emitted) and its back end (the latest light emitted), the complete "light-train" thus arrives at the observer over a much smaller time period (ten or twenty years) giving the illusion of faster than light travel.

This explanation depends on the jet making a sufficiently narrow angle with the observer's line-of-sight to explain the degree of superluminal motion seen in a particular case.[1]

Superluminal motion is often seen in two opposing jets, one moving away and one toward Earth. If Doppler shifts are observed in both sources, the velocity and the distance can be determined independently of other observations.

Some contrary evidence

As early as 1983, at the "superluminal workshop" held at Jodrell Bank Observatory, referring to the seven then-known superluminal jets,

Schilizzi ... presented maps of arc-second resolution [showing the large-scale outer jets] ... which ... have revealed outer double structure in all but one (3C 273) of the known superluminal sources. An embarrassment is that the average projected size [on the sky] of the outer structure is no smaller than that of the normal radio-source population.[2]

In other words, the jets are evidently not, on average, close to our line-of-sight. (Their apparent length would appear much shorter if they were.)

In 1993, Thomson et al. suggested that the (outer) jet of the quasar 3C 273 is nearly collinear to our line-of-sight. Superluminal motion of up to ~9.6c has been observed along the (inner) jet of this quasar.[3]

Superluminal motion of up to 6c has been observed in the inner parts of the jet of M87. To explain this in terms of the "narrow-angle" model, the jet must be no more than 19° from our line-of-sight.[4] But evidence suggests that the jet is in fact at about 43° to our line-of-sight.[5] The same group of scientists later revised that finding and argue in favour of a superluminal bulk movement in which the jet is embedded.[6]

Suggestions of turbulence and/or "wide cones" in the inner parts of the jets have been put forward to try to counter such problems, and there seems to be some evidence for this.[7]

Signal velocity

The model identifies a difference between the information carried by the wave at its signal velocity c, and the information about the wave front's apparent rate of change of position. If you envisage a light pulse in a wave guide (glass tube) moving across an observer's field of view, the pulse can only move at c through the guide. If that pulse is also directed towards the observer they will receive that wave information, at c. If the wave guide is moved in the same direction as the pulse the information on its position, passed to the observer as lateral emissions from the pulse, changes. They may see the rate of change of position as apparently representing motion faster than c when calculated, like the edge of a shadow across a curved surface. This is a different signal, containing different information, to the pulse and does not break the 2nd postulate of special relativity. c is strictly maintained in all local fields.

Derivation of the apparent velocity

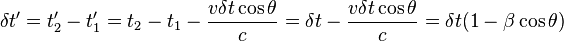

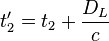

A relativistic jet coming out of the center of an active galactic nucleus is moving along AB with a velocity v. We are observing the jet from the point O. At time  a light ray leaves the jet from point A and another ray leaves at time

a light ray leaves the jet from point A and another ray leaves at time  from point B. Observer at O receives the rays at time

from point B. Observer at O receives the rays at time  and

and  respectively. The angle

respectively. The angle  is small enough that the two distances marked

is small enough that the two distances marked  can be considered equal.

can be considered equal.

-

, where

, where

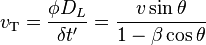

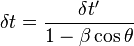

Apparent transverse velocity along  ,

,

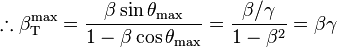

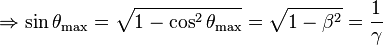

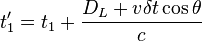

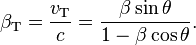

The apparent transverse velocity is maximal for angle ( is used)

is used)

-

, where

, where

If  (i.e. when velocity of jet is close to the velocity of light) then

(i.e. when velocity of jet is close to the velocity of light) then  despite the fact that

despite the fact that  . And of course

. And of course  means that the apparent transverse velocity along

means that the apparent transverse velocity along  , the only velocity on the sky that we can measure, is larger than the velocity of light in vacuum, i.e. the motion is apparently superluminal.

, the only velocity on the sky that we can measure, is larger than the velocity of light in vacuum, i.e. the motion is apparently superluminal.

History

Superluminal motion was first observed in 1902 by Jacobus Kapteyn in the ejecta of the nova GK Persei, which had exploded in 1901.[8] His discovery was published in the German language in the journal Astronomische Nachrichten, and received little attention from English-speaking astronomers until many decades later.[9][10]

In 1966 Martin Rees pointed out that "an object moving relativistically in suitable directions may appear to a distant observer to have a transverse velocity much greater than the velocity of light".[11] In 1969 and 1970 such sources were found as very distant astronomical radio sources, such as radio galaxies and quasars.[12][13][14] They were called superluminal sources. The discovery was the result of a new technique called Very Long Baseline Interferometry, which allowed astronomers to set limits to the angular size of components and to determine positions to better than milli-arcseconds and in particular to determine the change in positions on the sky, called proper motions in a timespan of typically years. The apparent velocity is obtained by multiplying the observed proper motion by the distance and could be up to 6 times the speed of light.

In the introduction to a workshop on superluminal radio sources, Pearson and Zensus reported

"The first indications of changes in the structure of some sources were obtained by an American-Australian team in a series of transpacific VLBI observations between 1968 and 1970 (Gubbay et al. 1969[12]). Following the early experiments, they had realised the potential of the NASA tracking antennas for VLBI measurements and set up an interferometer operating between California and Australia. The change in the source visibility that they measured for 3C 279, combined with changes in total flux density, indicated that a component first seen in 1969 had reached a diameter of about 1 milliarcsecond, implying expansion at an apparent velocity of at least twice the speed of light. Aware of Rees's model,[11] (Moffet et al. 1972[15]) concluded that their measurement presented evidence for relativistic expansion of this component. This interpretation, although by no means unique, was later confirmed, and in hindsight it seems fair to say that their experiment was the first interferometric measurement of superluminal expansion."[16]

In 1994, a Galactic speed record was obtained with the discovery of a superluminal source in our own Galaxy, the cosmic x-ray source GRS 1915+105. The expansion occurred on a much shorter timescale. Several separate blobs were seen to expand in pairs within weeks by typically 0.5 arcsec.[17] Because of the analogy with quasars, this source was called a microquasar.

See also

Notes

- ↑ See http://www.mhhe.com/physsci/astronomy/fix/student/chapter24/24f10.html for a graph of angle versus apparent speeds for two given actual relativistic speeds.

- ↑ Porcas, Richard (1983). "Superluminal motions: Astronomers still puzzled". Nature 302 (5911): 753. Bibcode:1983Natur.302..753P. doi:10.1038/302753a0.

- ↑ Thomson, R. C.; MacKay, C. D.; Wright, A. E. (1993). "Internal structure and polarization of the optical jet of the quasar 3C273". Nature 365 (6442): 133. Bibcode:1993Natur.365..133T. doi:10.1038/365133a0.; Pearson, T. J.; Unwin, S. C.; Cohen, M. H.; Linfield, R. P.; Readhead, A. C. S.; Seielstad, G. A.; Simon, R. S.; Walker, R. C. (1981). "Superluminal expansion of quasar 3C273". Nature 290 (5805): 365. Bibcode:1981Natur.290..365P. doi:10.1038/290365a0.; Davis, R. J.; Unwin, S. C.; Muxlow, T. W. B. (1991). "Large-scale superluminal motion in the quasar 3C273". Nature 354 (6352): 374. Bibcode:1991Natur.354..374D. doi:10.1038/354374a0.

- ↑ Biretta, John A.; Junor, William; Livio, Mario (1999). "Formation of the radio jet in M87 at 100 Schwarzschild radii from the central black hole". Nature 401 (6756): 891. Bibcode:1999Natur.401..891J. doi:10.1038/44780. ; Biretta, J. A.; Sparks, W. B.; MacChetto, F. (1999). "Hubble Space TelescopeObservations of Superluminal Motion in the M87 Jet". The Astrophysical Journal 520 (2): 621. Bibcode:1999ApJ...520..621B. doi:10.1086/307499.

- ↑ Biretta, J. A.; Zhou, F.; Owen, F. N. (1995). "Detection of Proper Motions in the M87 Jet". The Astrophysical Journal 447: 582. Bibcode:1995ApJ...447..582B. doi:10.1086/175901.

- ↑ Biretta, J. A.; Sparks, W. B.; MacChetto, F. (1999). "Hubble Space TelescopeObservations of Superluminal Motion in the M87 Jet". The Astrophysical Journal 520 (2): 621. Bibcode:1999ApJ...520..621B. doi:10.1086/307499.

- ↑ Biretta, John A.; Junor, William; Livio, Mario (1999). "Formation of the radio jet in M87 at 100 Schwarzschild radii from the central black hole". Nature 401 (6756): 891. Bibcode:1999Natur.401..891J. doi:10.1038/44780.

- ↑ http://iopscience.iop.org/1538-4357/600/1/L63/fulltext/

- ↑ Kapteyn's paper

- ↑ Index of citations to Kapteyn's paper

- 1 2 Rees, M. J. (1966). "Appearance of Relativistically Expanding Radio Sources". Nature 211 (5048): 468–470. Bibcode:1966Natur.211..468R. doi:10.1038/211468a0.

- 1 2 Gubbay, J.S.; Legg, A.J.; Robertson, D.S.; Moffet, A.T.; Ekers, R.D.; Seidel, B. (1969). "Variations of Small Quasar Components at 2,300 MHz". Nature 224 (5224): 1094–1095. Bibcode:1969Natur.224.1094G. doi:10.1038/2241094b0.

- ↑ Cohen, M. H.; Cannon, W.; Purcell, G. H.; Shaffer, D. B.; Broderick, J. J.; Kellermann, K. I.; Jauncey, D. L. (1971). "The Small-Scale Structure of Radio Galaxies and Quasi-Stellar Sources at 3.8 Centimeters". The Astrophysical Journal 170: 207. Bibcode:1971ApJ...170..207C. doi:10.1086/151204.

- ↑ Whitney, AR; Shapiro, Irwin I.; Rogers, Alan E. E.; Robertson, Douglas S.; Knight, Curtis A.; Clark, Thomas A.; Goldstein, Richard M.; Marandino, Gerard E.; Vandenberg, Nancy R. (1971). "Quasars Revisited: Rapid Time Variations Observed Via Very-Long-Baseline Interferometry". Science 173 (3993): 225–30. Bibcode:1971Sci...173..225W. doi:10.1126/science.173.3993.225. PMID 17741416.

- ↑ Moffet, A.T.; Gubbay, J.; Robertson, D.S.; Legg, A.J. (1972). Evans, D.S, ed. External Galaxies and Quasi-Stelar Objects : IAU Symposium 44, held in Uppsala, Sweden 10-14 August 1970. Dordrecht: Reidel. p. 228. ISBN 9027701997.

- ↑ J. Anton Zensus; Timothy J Pearson, eds. (1987). Superluminal Radio Sources : proceedings of a workshop in honor of Professor Marshall H. Cohen, held at Big Bear Solar Observatory, California, October 28-30, 1986. Cambridge New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 3. Bibcode:1987slrs.work....1P. ISBN 9780521345606.

- ↑ Mirabel, I.F.; Rodriguez, L.F. (1994). "A superluminal source in the Galaxy". Nature 371 (6492): 46–48. Bibcode:1994Natur.371...46M. doi:10.1038/371046a0.

External links

- A more detailed explanation.

- A mathematical deduction of superluminal motion.

- Superluminal motion Flash Applet.

![\frac{\partial\beta_\text{T}}{\partial\theta} = \frac{\partial}{\partial\theta} \left[\frac{\beta\sin\theta}{1-\beta\cos\theta}\right] = \frac{\beta\cos\theta}{1-\beta\cos\theta} - \frac{(\beta\sin\theta)^2}{(1-\beta\cos\theta)^2} = 0](../I/m/d6a448f7d69f2292308ae7cf3dfffed4.png)