Sun parakeet

| Sun parakeet | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Psittaciformes |

| Superfamily: | Psittacoidea |

| Family: | Psittacidae |

| Subfamily: | Arinae |

| Tribe: | Arini |

| Genus: | Aratinga |

| Species: | A. solstitialis |

| Binomial name | |

| Aratinga solstitialis (Linnaeus, 1758) | |

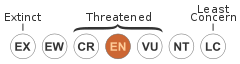

The sun parakeet or sun conure (Aratinga solstitialis) is a medium-sized brightly colored parrot native to northeastern South America. The adult male and female are similar in appearance, with predominantly golden-yellow plumage and orange-flushed underparts and face. Sun conures are very social birds, typically living in flocks. They form monogamous pairs for reproduction and nest in palm cavities in the tropics. Sun conures mainly feeds on fruits, flowers, berries, blossoms, seeds, nuts and insects. Conures are commonly bred and kept in aviculture and may live up to 30 years. This species is currently threatened by loss of habitat and trapping for plumage or the pet trade. Sun conures are now listed as endangered by the IUCN.[1]

Taxonomy

The sun parakeet was one of the many species originally described by Linnaeus in his 18th-century work Systema Naturae.[2] As Linnaeus did with many of the parrots he described, he placed this species in the genus Psittacus, but it has since been moved to the widely accepted Aratinga, which contains a number of similar New World species, while Psittacus is now restricted to the type species, the African grey parrot. The specific epithet solstitialis is derived from the Latin for 'of the summer solstice', hence 'sunny', and refers to its golden plumage.[3] There are two widely used common names: Sun Conure, used in aviculture and by some authorities such as Thomas Arndt, and Sun Parakeet as used by the AOU and widely in official birdlists, field guides, and by birders.[4]

The sun parakeet is monotypic, but the Aratinga solstitialis complex includes three additional species from Brazil: jandaya parakeet, golden-capped parakeet, and sulphur-breasted parakeet. These have all been considered subspecies of the sun parakeet, but most recent authorities maintain their status as separate species. Alternatively, it has been suggested that the sun parakeet and the sulphur-breasted parakeet represent one species, while the jenday parakeet and golden-capped parakeet represent a second. Of these, the sulphur-breasted parakeet only received widespread recognition in 2005, having gone unnoticed at least partially due to its resemblance to certain pre-adult plumages of the sun parakeet. The sun, jandaya, and golden-capped parakeets will all interbreed in captivity (it is likely, but unconfirmed, that the Sulphur-breasted also will interbreed with these). In the wild, hybrids between the jandaya parakeet and golden-capped parakeet have been reported in their limited area of contact, but it has been speculated that most such individuals could be sub-adults (which easily could be confused with hybrids). As far as known, the remaining taxa are entirely allopatric, although it is possible that the sun parakeet and the sulphur-breasted parakeet come into contact in the southern Guianas, where some doubts exists over the exact identity.[5]

Description

On average, sun parakeets weigh approximately 110 g (4 oz) and are around 30 cm (12 in) long.[6] They are sexually monomorphic.

Adults have a rich yellow crown, nape, mantle, lesser wing-coverts, tips of the greater wing-coverts, chest, and underwing-coverts. The face and belly are orange with red around the ears. The base of the greater wing-coverts, tertials, and base of the primaries are green, while the secondaries, tips of the primaries, and most of the primary coverts are dark blue. The tail is olive-green with a blue tip. From below, all the flight feathers are dark greyish. The bill is black. The legs and the bare eye-ring are grey, but the latter often fades to white in captivity (so using amount of grey or white in the eye-ring for determining "purity" of an individual can be misleading). It is easily confused with the closely related jandaya parakeet and sulphur-breasted parakeet, but the former has entirely green wing-coverts, mantle and vent, while the latter has green mottling to the mantle and less orange to the underparts. The sun parakeet is also superficially similar to the pale-billed golden parakeet.

Juvenile sun parakeets display a predominantly green plumage and resemble similar-aged sulphur-breasted parakeets. The distinctive yellow, orange, and reddish colouration on the back, abdomen, and head is attained with maturity.[7]

Distribution and habitat

Sun conures live in northeastern South America. It only occurs in a relatively small region of north-eastern South America: the north Brazilian state of Roraima, southern Guyana, extreme southern Suriname, and southern French Guiana. It also occurs as a vagrant to coastal French Guiana. Its status in Venezuela is unclear, but there are recent sightings from the south-east near Santa Elena de Uairén. It may occur in Amapá or far northern Pará (regions where the avifauna generally is very poorly documented), but this remains to be confirmed. Populations found along the Amazon River in Brazil are now known to belong to the sulphur-breasted parakeet.[8]

Sun conures are mostly found in tropical habitats but its exact ecological requirements remain relatively poorly known. It is widely reported as occurring within dry savanna woodlands and coastal forests, but recent sightings suggest it mainly occurs at altitudes less than 1200 meters, at the edge of humid forests growing in foothills in the Guiana Shield, and crosses more open savannah habitats only when traveling between patches of forest. Sun conures have been seen in shrublands along the Amazon riverbank as well as forested valleys and coastal seasonally flooded forests. These conures usually inhabitat fruiting trees and palm groves.[9]

Behaviour

Like other members of the genus Aratinga, the sun parakeet is very social and typically occurs in large flocks of 20 to 30 individuals. They rarely leave the flock but when they get separated from the group they squawk and scream in a high pitch voice which can be carried for hundreds of yards, allowing individuals to communicate with their flock and return to them. Flocks are relatively quiet while feeding but are known to be very vocal and make loud noises when in flight. They can travel many miles in a single day and they are fast direct flyers. Nonverbal communication is also practiced with a variety of physical displays. Birds within a flock will rest, feed one another, preen, and bathe throughout the daylight hours. They move through the trees using their beaks for extra support. They also have the ability to use their feet like hands to help hold, examine, or eat items.[10] Sun conures have been reported to nest in palm cavities. When in molt, conures are uncomfortable and therefore easily irritable. Bathing, warm rainfalls and humidity allow the sheaths of each pin feather to open more easily and lessen their discomfort. Sun conures are extremely smart and curious, therefore require constant mental stimulation and social interaction. Their speech and ability to learn tricks in captivity is quite moderate. Otherwise, relatively little is known about their behavior in the wild, in part due to confusion with the sulphur-breasted parakeet species. Regardless, the behavior of the two is unlikely to differ to any great extent.[11]

Diet

In the wild, sun conures mainly feeds on fruits, flowers, berries, blossoms, seeds, nuts and insects. They feed on both ripe and half-ripe seeds of both fruits and berries. They also eat red cactus fruit, Malpighia berries and legume pods. At times, they forage from agricultural crops and may be consisdered pests. They require more protein intake during breeding season, more carbohydrates when rearing young and more calcium during egg production.

In captivity, their diets may include grass seeds, beans, nuts, fruits (apples, papaya, bananas, oranges, grapefruits, strawberries, raspberries, blackberries, gooseberries, currants, rowans, elderberries, hawthorn berries, rose hips, cucumbers and tomatoes), and vegetables (spinach, Chinese cabbage, cress, roquette, kale, broccoli, carrots, alfalfa, peas, endive, and sweet potatoes), dandelions, chickweed, soaked corn, germinated sunflower seeds and spray millet. They may also eat fruit tree buds (elderberry bushes, willows, hawthorn, and aspen), ant eggs, mealworms or their substitutes (hard-boiled eggs, bread, biscuits, hard cheese or low-fat cottage cheese). Cuttle bones, mineral blocks, and gravel or ground oyster shells may be given to aid in mechanical digestion.[11]

Reproduction

Young sun conures form monagamous pairs at about 4 to 5 months of age. Prior to breeding they may be seen feeding and grooming one another. Mating can last up to three minutes, after which pairs become very affectionate with each other. Prior to egg laying, the female's abdomen will noticeably swell. They have been known to nest in trees or in cavities of Maurita flexuosa palms. Fertility rate of sun conures is relatively high. Average clutch size is 3 to 4 eggs and they may be laid in in two to three day intervals. Pairs may only destroy and eat their eggs in cases of calcium deficiency. Females are responsible for the entire incubation period from 23 to 27 days and only leave the nest for short feeding periods. Males aggressively protect the nest from potential predators. Eggs may fail to hatch if they are not kept warm or if the bird fails to break through the shell successfully, which may take from a few hours to a couple of days. Chicks are born altricial, therefore they are blind, naked and completely vulnerable. Only after 10 days, they begin to open their eyes and their feather quills break through. Both the mother and father participate in feeding the chicks. The young depend on their parents for 7 to 8 weeks after hatching and only become independent after 9 to 10 weeks. Conures are sexually mature at around 2 years of age and have a lifespan ranging from 25 to 30 years.[11]

Status

Sun conures are currently endangered. Unfortunately, their population numbers are declining exponentially due to loss of habitat, hunting for plumage and being excessively wild caught -about 800,000 each year, for the pet trade. Now there are more sun conures living in people's homes than in the wild. Since the Wild Bird Conservation Act was put in place in 1992 to ban the importation of parrots (including sun conures) into the United States, they are more frequently breed in captivity for domestication purposes. Similarly, the European Union more recently banned the importation of wild caught birds in 2007. These legislations may help increase their population numbers in the wild[12]

In the past, the sun parakeet has been considered safe and listed as Least Concern, but recent surveys in southern Guyana (where previously considered common) and the Brazilian state Roraima have revealed that it possibly is extirpated from the former and rare in the latter. It is very rare in French Guiana, but may breed in the southern part of the country (this remains unconfirmed). Today it is regularly bred in captivity, but the capture of wild individuals potentially remains a very serious threat. This has fueled recent discussions regarding its status, leading to it being uplisted to Endangered in the 2008 IUCN Red List.[1]

Aviculture

The sun conure is noted for its very loud squawks and screams compared to its relatively small size. It is capable of mimicking humans, but not as well as some larger parrots. Sun conures are popular as pets because of their bright coloration and curious nature. Due to their inquisitive temperaments, they demand a great deal of attention from their owners, with whom they can be loving and cuddly with. Hand reared pets can be very friendly towards people that they are familiar with, but they may be aggressive with strangers and even territorial with visitors.[13] Sun conures are capable of learning a great deal of tricks and can even perform in front of a live audience. They enjoy listening to music, to which they occasionally sing and dance to. Like many parrots, they are determined chewers and require toys and treats to chew on. Many owners clips their conure's wings but this is not necessary if the proper precautions are put in place. Due to environmental hazrds, conures should not be allowed to fly unsupervised. Sun conures are great candidates for outdoor flight when well trained as they are loyal but risk potential must be minimized. In captivity, their lifespan ranges from 15 to 30 years.[9]

References

- 1 2 3 BirdLife International (2014). "Aratinga solstitialis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2014.3. International Union for Conservation of Nature. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

- ↑ Linnaeus, C (1758). Systema naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. Tomus I. Editio decima, reformata. (in Latin). Holmiae. (Laurentii Salvii). p. 824.

- ↑ Simpson, D.P. (1979). Cassell's Latin Dictionary (5 ed.). London, United Kingdom: Cassell Ltd. ISBN 0-304-52257-0.

- ↑ Arndt, T. (1997). Lexicon of Parrots. Arndt Verlag. ISBN 3-9805291-1-8

- ↑ Silverira, L., de Lima, F., & Höfling, E. (2005). A new species of Aratinga Conure (Psittaformes: Psittacidae) from Brazil, with taxonomical remarks on the Aratinga solstitialis complex. The Auk 122(1): 292–305.

- ↑ Sun Conure Parrot. PBase.com

- ↑ "Sun Conure: General". Sun Conure.

- ↑ "Sun Conure". Beauty of Birds.

- 1 2 "Sun-conure-parrot". Feather me.

- ↑ http://www.iaate.org/companion-parrots/51-content/resource-center/202-sun-conure-fact-sheet.html

- 1 2 3 "Aratinga solstialis". Animal Diversity Web.

- ↑ "Sun conures". My conure.

- ↑ Sun Conure. theparrotplace.co.nz

Further reading

- Hilty, S. (2003). Birds of Venezuela, 2nd edition. Princeton University Press, New Jersey. ISBN 0-691-02131-7

- Juniper, T., & Parr, M. (1998). A Guide to the Parrots of the World. Pica Press, East Sussex. ISBN 1-873403-40-2

- Jutglar, Á. (1997). Aratinga solstitialis (Sun Conure). p. 431 in: del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., & Sargatal, J. eds (1997). Handbook of Birds of the World. Vol. 4. Sandgrouse to Cuckoos. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona. ISBN 84-87334-22-9

- Restall, R., Rodner, C., & Lentino, M. (2006). Birds of Northern South America – An Identification Guide. Vol. 1: Species Accounts. Helm, London. ISBN 0-7136-7242-0

- Sun Conure (Aratinga solstitialis): uplist to Near Threatened? BirdLife International discussion board.

- Recognize Aratinga pintoi as a valid species. South American Classification Committee.

- Teitler, R., 1981. Taming and Training Conures. T.F.H. Publications, Inc. Ltd. England.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Aratinga_solstitialis. |

- "Sun parakeet – BirdLife Species Factsheet". BirdLife International (2008). Retrieved 3 January 2009.

- Stamps (for Guyana) with RangeMap

- "Sun conure". Beauty of birds (2015). http://beautyofbirds.com/sunconure.html. Retrieved 15 September 2015.

- "Habitat and behaviour". Encyclopedia of life (2015). http://eol.org/pages/1177978/details#Habitat_and_behavior. Retrieved 15 September 2015.

- "Sun conure parrot". Feather me (2015). http://www.featherme.com/index.php/parrot-species/sun-conure-parrot/. Retrieved 15 September 2015.

- "Endangered in the wild but still popular pets". My conure (2015). http://myconure.com/conure-species/sun-conures-endangered-in-the-wild-but-still-popular-pets/. Retrieved 15 September 2015.

- "Aratinga solstitialis". Animal diversity (2015). http://animaldiversity.org/accounts/Aratinga_solstitialis/. Retriever 15 September 2015.