Mali

Coordinates: 17°N 4°W / 17°N 4°W

| Republic of Mali |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||

| Motto: "Un peuple, un but, une foi" (French) "One nation, one goal, one faith" |

||||||

| Anthem: Le Mali (French)[1] | ||||||

.svg.png) Location of Mali (dark blue) – in Africa (light blue & dark grey) |

||||||

_-_MLI_-_UNOCHA.svg.png) |

||||||

| Capital and largest city | Bamako 12°39′N 8°0′W / 12.650°N 8.000°W | |||||

| Official languages | French | |||||

| Vernacular languages | Bambara | |||||

| Ethnic groups | ||||||

| Demonym | Malian | |||||

| Government | Unitary semi-presidential republic | |||||

| • | President | Ibrahim Boubacar Keïta | ||||

| • | Prime Minister | Modibo Keita | ||||

| Legislature | National Assembly | |||||

| Independence | ||||||

| • | from Francea | 20 June 1960 | ||||

| • | as Mali | 22 September 1960 | ||||

| Area | ||||||

| • | Total | 1,240,192 km2 (24th) 478,839 sq mi |

||||

| • | Water (%) | 1.6 | ||||

| Population | ||||||

| • | April 2009 census | 14,517,176[2] (67th) | ||||

| • | Density | 11.7/km2 (215th) 30.3/sq mi |

||||

| GDP (PPP) | 2012 estimate | |||||

| • | Total | $17.983 billion[3] | ||||

| • | Per capita | $1,100[3] | ||||

| GDP (nominal) | 2012 estimate | |||||

| • | Total | $10.319 billion[3] | ||||

| • | Per capita | $631[3] | ||||

| Gini (2010) | 33.0[4] medium |

|||||

| HDI (2013) | low · 176th |

|||||

| Currency | West African CFA franc (XOF) | |||||

| Time zone | GMT (UTC+0) | |||||

| • | Summer (DST) | not observed (UTC+0) | ||||

| Drives on the | right[6] | |||||

| Calling code | +223 | |||||

| ISO 3166 code | ML | |||||

| Internet TLD | .ml | |||||

| a. | As the Sudanese Republic, with Senegal as the Mali Federation. | |||||

Mali (![]() i/ˈmɑːli/; French: [maˈli]), officially the Republic of Mali (French: République du Mali), is a landlocked country in West Africa. Mali is the eighth-largest country in Africa, with an area of just over 1,240,000 square kilometres (480,000 sq mi). The population of Mali is 14.5 million. Its capital is Bamako. Mali consists of eight regions and its borders on the north reach deep into the middle of the Sahara Desert, while the country's southern part, where the majority of inhabitants live, features the Niger and Senegal rivers. The country's economy centers on agriculture and fishing. Some of Mali's prominent natural resources include gold, being the third largest producer of gold in the African continent,[7] and salt. About half the population lives below the international poverty line of $1.25 (U.S.) a day.[8] A majority of the population (55%) are non-denominational Muslims.[9]

i/ˈmɑːli/; French: [maˈli]), officially the Republic of Mali (French: République du Mali), is a landlocked country in West Africa. Mali is the eighth-largest country in Africa, with an area of just over 1,240,000 square kilometres (480,000 sq mi). The population of Mali is 14.5 million. Its capital is Bamako. Mali consists of eight regions and its borders on the north reach deep into the middle of the Sahara Desert, while the country's southern part, where the majority of inhabitants live, features the Niger and Senegal rivers. The country's economy centers on agriculture and fishing. Some of Mali's prominent natural resources include gold, being the third largest producer of gold in the African continent,[7] and salt. About half the population lives below the international poverty line of $1.25 (U.S.) a day.[8] A majority of the population (55%) are non-denominational Muslims.[9]

Present-day Mali was once part of three West African empires that controlled trans-Saharan trade: the Ghana Empire, the Mali Empire (for which Mali is named), and the Songhai Empire. During its golden age, there was a flourishing of mathematics, astronomy, literature, and art.[10][11] At its peak in 1300, the Mali Empire covered an area about twice the size of modern-day France and stretched to the west coast of Africa.[12] In the late 19th century, during the Scramble for Africa, France seized control of Mali, making it a part of French Sudan. French Sudan (then known as the Sudanese Republic) joined with Senegal in 1959, achieving independence in 1960 as the Mali Federation. Shortly thereafter, following Senegal's withdrawal from the federation, the Sudanese Republic declared itself the independent Republic of Mali. After a long period of one-party rule, a coup in 1991 led to the writing of a new constitution and the establishment of Mali as a democratic, multi-party state.

In January 2012, an armed conflict broke out in northern Mali, which Tuareg rebels took control of by April and declared the secession of a new state, Azawad.[13] The conflict was complicated by a military coup that took place in March[14] and later fighting between Tuareg and Islamist rebels. In response to Islamist territorial gains, the French military launched Opération Serval in January 2013.[15] A month later, Malian and French forces recaptured most of the north. Presidential elections were held on 28 July 2013, with a second round run-off held on 11 August, and legislative elections were held on 24 November and 15 December 2013.

History

Mali was once part of three famed West African empires which controlled trans-Saharan trade in gold, salt, slaves, and other precious commodities.[16] These Sahelian kingdoms had neither rigid geopolitical boundaries nor rigid ethnic identities.[16] The earliest of these empires was the Ghana Empire, which was dominated by the Soninke, a Mande-speaking people.[16] The empire expanded throughout West Africa from the 8th century until 1078, when it was conquered by the Almoravids.[17]

The Mali Empire later formed on the upper Niger River, and reached the height of power in the 14th century.[17] Under the Mali Empire, the ancient cities of Djenné and Timbuktu were centers of both trade and Islamic learning.[17] The empire later declined as a result of internal intrigue, ultimately being supplanted by the Songhai Empire.[17] The Songhai people originated in current northwestern Nigeria. The Songhai had long been a major power in West Africa subject to the Mali Empire's rule.[17]

In the late 14th century, the Songhai gradually gained independence from the Mali Empire and expanded, ultimately subsuming the entire eastern portion of the Mali Empire.[17] The Songhai Empire's eventual collapse was largely the result of a Moroccan invasion in 1591, under the command of Judar Pasha.[17] The fall of the Songhai Empire marked the end of the region's role as a trading crossroads.[17] Following the establishment of sea routes by the European powers, the trans-Saharan trade routes lost significance.[17]

One of the worst famines in the region's recorded history occurred in the 18th century. According to John Iliffe, "The worst crises were in the 1680s, when famine extended from the Senegambian coast to the Upper Nile and 'many sold themselves for slaves, only to get a sustenance', and especially in 1738–56, when West Africa's greatest recorded subsistence crisis, due to drought and locusts, reportedly killed half the population of Timbuktu."[18]

French colonial rule

Mali fell under the control of France during the late 19th century.[17] By 1905, most of the area was under firm French control as a part of French Sudan.[17] In early 1959, French Sudan (which changed its name to the Sudanese Republic) and Senegal united to become the Mali Federation. The Mali Federation gained independence from France on 20 June 1960.[17]

Senegal withdrew from the federation in August 1960, which allowed the Sudanese Republic to become the independent Republic of Mali on 22 September 1960. Modibo Keïta was elected the first president.[17] Keïta quickly established a one-party state, adopted an independent African and socialist orientation with close ties to the East, and implemented extensive nationalization of economic resources.[17] In 1960, the population of Mali was reported to be about 4.1 million.[19]

Moussa Traoré

On 19 November 1968, following progressive economic decline, the Keïta regime was overthrown in a bloodless military coup led by Moussa Traoré,[20] a day which is now commemorated as Liberation Day. The subsequent military-led regime, with Traoré as president, attempted to reform the economy. His efforts were frustrated by political turmoil and a devastating drought between 1968 to 1974,[20] in which famine killed thousands of people.[21] The Traoré regime faced student unrest beginning in the late 1970s and three coup attempts. The Traoré regime repressed all dissenters until the late 1980s.[20]

The government continued to attempt economic reforms, and the populace became increasingly dissatisfied.[20] In response to growing demands for multi-party democracy, the Traoré regime allowed some limited political liberalization. They refused to usher in a full-fledged democratic system.[20] In 1990, cohesive opposition movements began to emerge, and was complicated by the turbulent rise of ethnic violence in the north following the return of many Tuaregs to Mali.[20]

Anti-government protests in 1991 led to a coup, a transitional government, and a new constitution.[20] Opposition to the corrupt and dictatorial regime of General Moussa Traoré grew during the 1980s. During this time strict programs, imposed to satisfy demands of the International Monetary Fund, brought increased hardship upon the country's population, while elites close to the government supposedly lived in growing wealth. Peaceful student protests in January 1991 were brutally suppressed, with mass arrests and torture of leaders and participants.[22] Scattered acts of rioting and vandalism of public buildings followed, but most actions by the dissidents remained nonviolent.[22]

March Revolution

From 22 March through 26 March 1991, mass pro-democracy rallies and a nationwide strike was held in both urban and rural communities, which became known as les evenements ("the events") or the March Revolution. In Bamako, in response to mass demonstrations organized by university students and later joined by trade unionists and others, soldiers opened fire indiscriminately on the nonviolent demonstrators. Riots broke out briefly following the shootings. Barricades as well as roadblocks were erected and Traoré declared a state of emergency and imposed a nightly curfew. Despite an estimated loss of 300 lives over the course of four days, nonviolent protesters continued to return to Bamako each day demanding the resignation of the dictatorial president and the implementation of democratic policies.[23]

26 March 1991 is the day that marks the clash between military soldiers and peaceful demonstrating students which climaxed in the massacre of dozens under the orders of then President Moussa Traoré. He and three associates were later tried and convicted and received the death sentence for their part in the decision-making of that day. Nowadays, the day is a national holiday in order to remember the tragic events and the people that were killed.[24] The coup is remembered as Mali's March Revolution of 1991.

By 26 March, the growing refusal of soldiers to fire into the largely nonviolent protesting crowds turned into a full-scale tumult, and resulted into thousands of soldiers putting down their arms and joining the pro-democracy movement. That afternoon, Lieutenant Colonel Amadou Toumani Touré announced on the radio that he had arrested the dictatorial president, Moussa Traoré. As a consequence, opposition parties were legalized and a national congress of civil and political groups met to draft a new democratic constitution to be approved by a national referendum.[23]

Amadou Toumani Touré presidency

In 1992, Alpha Oumar Konaré won Mali's first democratic, multi-party presidential election, before being re-elected for a second term in 1997, which was the last allowed under the constitution. In 2002 Amadou Toumani Touré, a retired general who had been the leader of the military aspect of the 1991 democratic uprising, was elected.[25] During this democratic period Mali was regarded as one of the most politically and socially stable countries in Africa.[26]

Slavery persists in Mali today with as many as 200,000 people held in direct servitude to a master.[27] In the Tuareg Rebellion of 2012, ex-slaves were a vulnerable population with reports of some slaves being recaptured by their former masters.[28]

Northern Mali conflict

In January 2012 a Tuareg rebellion began in Northern Mali, led by the National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad.[29] In March, military officer Amadou Sanogo seized power in a coup d'état, citing Touré's failures in quelling the rebellion, and leading to sanctions and an embargo by the Economic Community of West African States.[30] The MNLA quickly took control of the north, declaring independence as Azawad.[31] However, Islamist groups including Ansar Dine and Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM), who had helped the MNLA defeat the government, turned on the Tuareg and took control of the North[32] with the goal of implementing sharia in Mali.[33]

On 11 January 2013, the French Armed Forces intervened at the request of the interim government. On 30 January, the coordinated advance of the French and Malian troops claimed to have retaken the last remaining Islamist stronghold of Kidal, which was also the last of three northern provincial capitals.[34] On 2 February, the French President, François Hollande, joined Mali's interim President, Dioncounda Traoré, in a public appearance in recently recaptured Timbuktu.[35]

Geography

Mali is a landlocked country in West Africa, located southwest of Algeria. It lies between latitudes 10° and 25°N, and longitudes 13°W and 5°E. Mali is bordered by Algeria to the north, Niger to the east, Burkina Faso and Côte d'Ivoire to the south, Guinea to the south-west, and Senegal and Mauritania to the west.

At 1,242,248 square kilometres (479,635 sq mi), including the disputed region of Azawad, Mali is the world's 24th-largest country and is comparable in size to South Africa or Angola. Most of the country lies in the southern Sahara Desert, which produces an extremely hot, dust-laden Sudanian savanna zone.[36] Mali is mostly flat, rising to rolling northern plains covered by sand. The Adrar des Ifoghas massif lies in the northeast.

Mali lies in the torrid zone and is among the hottest countries in the world. The thermal equator, which matches the hottest spots year-round on the planet based on the mean daily annual temperature, crosses the country.[36] Most of Mali receives negligible rainfall and droughts are very frequent.[36] Late June to early December is the rainy season in the southernmost area. During this time, flooding of the Niger River is common, creating the Inner Niger Delta.[36] The vast northern desert part of Mali has a hot desert climate (Köppen climate classification (BWh) with long, extremely hot summers and scarce rainfall which decreases northwards. The central area has a hot semi-arid climate (Köppen climate classification (BSh) with very high temperatures year-round, a long, intense dry season and a brief, irregular rainy season. The little southern band possesses a tropical wet and dry climate (Köppen climate classification (Aw) very high temperatures year-round with a dry season and a rainy season.

Mali has considerable natural resources, with gold, uranium, phosphates, kaolinite, salt and limestone being most widely exploited. Mali is estimated to have in excess of 17,400 tonnes of uranium (measured + indicated + inferred).[37][38] In 2012, a further uranium mineralized north zone was identified.[39] Mali faces numerous environmental challenges, including desertification, deforestation, soil erosion, and inadequate supplies of potable water.[36]

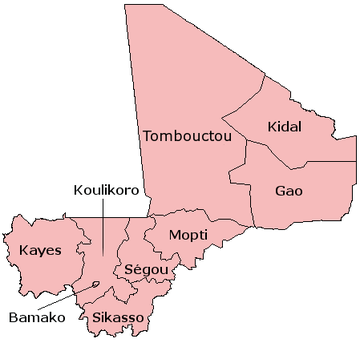

Regions and cercles

Mali is divided into eight regions (régions) and one district.[40] Each region has a governor.[41] Since Mali's regions are very large, the country is subdivided into 49 cercles and 703 communes.[42]

The régions and Capital District are:

| Region name | Area (km2) | Population Census 1998 | Population Census 2009 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kayes | 119,743 | 1,374,316 | 1,996,812 |

| Koulikoro | 95,848 | 1,570,507 | 2,418,305 |

| Bamako Capital District | 252 | 1,016,296 | 1,809,106 |

| Sikasso | 70,280 | 1,782,157 | 2,625,919 |

| Ségou | 64,821 | 1,675,357 | 2,336,255 |

| Mopti | 79,017 | 1,484,601 | 2,037,330 |

| Tombouctou (Timbuktu) | 496,611 | 442,619 | 681,691 |

| Gao | 170,572 | 341,542 | 544,120 |

| Kidal | 151,430 | 38,774 | 67,638 |

Extent of central government control

In March 2012, the Malian government lost control over Tombouctou, Gao and Kidal Regions and the north-eastern portion of Mopti Region. On 6 April 2012, the National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad unilaterally declared their secession from Mali as Azawad, an act that neither Mali nor the international community recognised.[43] The government later regained control over these areas.

Politics and government

Until the military coup of 22 March 2012[14][44] and a second military coup in December 2012,[45] Mali was a constitutional democracy governed by the Constitution of 12 January 1992, which was amended in 1999.[46] The constitution provides for a separation of powers among the executive, legislative, and judicial branches of government.[46] The system of government can be described as "semi-presidential".[46] Executive power is vested in a president, who is elected to a five-year term by universal suffrage and is limited to two terms.[46][47]

The president serves as a chief of state and commander in chief of the armed forces.[46][48] A prime minister appointed by the president serves as head of government and in turn appoints the Council of Ministers.[46][49] The unicameral National Assembly is Mali's sole legislative body, consisting of deputies elected to five-year terms.[50][51] Following the 2007 elections, the Alliance for Democracy and Progress held 113 of 160 seats in the assembly.[52] The assembly holds two regular sessions each year, during which it debates and votes on legislation that has been submitted by a member or by the government.[50][53]

Mali's constitution provides for an independent judiciary,[50][54] but the executive continues to exercise influence over the judiciary by virtue of power to appoint judges and oversee both judicial functions and law enforcement.[50] Mali's highest courts are the Supreme Court, which has both judicial and administrative powers, and a separate Constitutional Court that provides judicial review of legislative acts and serves as an election arbiter.[50][55] Various lower courts exist, though village chiefs and elders resolve most local disputes in rural areas.[50]

Foreign relations

Mali's foreign policy orientation has become increasingly pragmatic and pro-Western over time.[56] Since the institution of a democratic form of government in 2002, Mali's relations with the West in general and with the United States in particular have improved significantly.[56] Mali has a longstanding yet ambivalent relationship with France, a former colonial ruler.[56] Mali was active in regional organizations such as the African Union until its suspension over the 2012 Malian coup d'état.[56][57]

Working to control and resolve regional conflicts, such as in Ivory Coast, Liberia, and Sierra Leone, is one of Mali's major foreign policy goals.[56] Mali feels threatened by the potential for the spillover of conflicts in neighboring states, and relations with those neighbors are often uneasy.[56] General insecurity along borders in the north, including cross-border banditry and terrorism, remain troubling issues in regional relations.[56]

Military

Mali's military forces consist of an army, which includes land forces and air force,[58] as well as the paramilitary Gendarmerie and Republican Guard, all of which are under the control of Mali's Ministry of Defense and Veterans, headed by a civilian.[59] The military is underpaid, poorly equipped, and in need of rationalization.[59]

Economy

.jpg)

The Central Bank of West African States handles the financial affairs of Mali and additional members of the Economic Community of West African States. Mali is one of the poorest countries in the world.[58] The average worker's annual salary is approximately US$1,500.[60]

Mali underwent economic reform, beginning in 1988 by signing agreements with the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund.[60] During 1988 to 1996, Mali's government largely reformed public enterprises. Since the agreement, sixteen enterprises were privatized, 12 partially privatized, and 20 liquidated.[60] In 2005, the Malian government conceded a railroad company to the Savage Corporation.[60] Two major companies, Societé de Telecommunications du Mali (SOTELMA) and the Cotton Ginning Company (CMDT), were expected to be privatized in 2008.[60]

Between 1992 and 1995, Mali implemented an economic adjustment programme that resulted in economic growth and a reduction in financial imbalances. The programme increased social and economic conditions, and led to Mali joining the World Trade Organization on 31 May 1995.[61]

Mali is also a member of the Organization for the Harmonization of Business Law in Africa (OHADA).[62] The gross domestic product (GDP) has risen since. In 2002, the GDP amounted to US$3.4 billion,[63] and increased to US$5.8 billion in 2005,[60] which amounts to an approximately 17.6 percent annual growth rate.

Mali is a part of "French Zone" (Zone Franc), which means that it uses CFA franc. Mali is connected with the French government by agreement since 1962 (creation of BCEAO). Today all seven countries of BCEAO (including Mali) are connected to French Central Bank.[64]

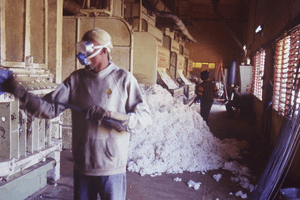

Agriculture

Mali's key industry is agriculture. Cotton is the country's largest crop export and is exported west throughout Senegal and Ivory Coast.[65][66] During 2002, 620,000 tons of cotton were produced in Mali but cotton prices declined significantly in 2003.[65][66] In addition to cotton, Mali produces rice, millet, corn, vegetables, tobacco, and tree crops. Gold, livestock and agriculture amount to 80% of Mali's exports.[60]

Eighty percent of Malian workers are employed in agriculture. 15 percent of Malian workers are employed in the service sector.[66] Seasonal variations lead to regular temporary unemployment of agricultural workers.[67]

Mining

In 1991, with the assistance of the International Development Association, Mali relaxed the enforcement of mining codes which led to renewed foreign interest and investment in the mining industry.[68] Gold is mined in the southern region and Mali has the third highest gold production in Africa (after South Africa and Ghana).[65]

The emergence of gold as Mali's leading export product since 1999 has helped mitigate some of the negative impact of the cotton and Ivory Coast crises.[69] Other natural resources include kaolin, salt, phosphate, and limestone.[60]

Energy

Electricity and water are maintained by the Energie du Mali, or EDM, and textiles are generated by Industry Textile du Mali, or ITEMA.[60] Mali has made efficient use of hydroelectricity, consisting of over half of Mali's electrical power. In 2002, 700 GWh of hydroelectric power were produced in Mali.[66]

Energie du Mali is an electric company that provides electricity to Mali citizens. Only 55% of the population in cities have access to EDM.[70]

Transport infrastructure

In Mali, there is a railway that connects to bordering countries. There are also approximately 29 airports of which 8 have paved runways. Urban areas are known for their large quantity of green and white taxicabs. A significant sum of the population is dependent on public transportation.

Society

Demographics

In July 2009, Mali's population was an estimated 14.5 million. The population is predominantly rural (68 percent in 2002), and 5–10 percent of Malians are nomadic.[71] More than 90 percent of the population lives in the southern part of the country, especially in Bamako, which has over 1 million residents.[71]

In 2007, about 48 percent of Malians were younger than 12 years old, 49 percent were 15–64 years old, and 3 percent were 65 and older.[58] The median age was 15.9 years.[58] The birth rate in 2014 is 45.53 births per 1,000, and the total fertility rate (in 2012) was 6.4 children per woman.[58][72] The death rate in 2007 was 16.5 deaths per 1,000.[58] Life expectancy at birth was 53.06 years total (51.43 for males and 54.73 for females).[58] Mali has one of the world's highest rates of infant mortality,[71] with 106 deaths per 1,000 live births in 2007.[58]

| | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Name | Region | Pop. | ||||||

Bamako Sikasso |

1 | Bamako | Bamako | 1 297 281 | |||||

| 2 | Sikasso | Sikasso | 144 786 | ||||||

| 3 | Mopti | Mopti | 108 456 | ||||||

| 4 | Koutiala | Sikasso | 99 353 | ||||||

| 5 | Kayes Ndi | Kayes | 97 464 | ||||||

| 6 | Ségou | Ségou | 92 552 | ||||||

| 7 | Gao | Gao | 87 000 | ||||||

| 8 | Kayes | Kayes | 78 406 | ||||||

| 9 | Morkala | Ségou | 53 738 | ||||||

| 10 | Kolokani | Koulikoro | 48 774 | ||||||

Ethnicity

Mali's population encompasses a number of sub-Saharan ethnic groups. The Bambara (Bambara: Bamanankaw) are by far the largest single ethnic group, making up 36.5 percent of the population.[71] Mali's official language is French, and over 40 African languages also are spoken by the various ethnic groups.[71] About 80 percent of Mali's population can communicate in Bambara, which serves as an important lingua franca.[71] Bambara is one of the 12 national languages recognized by the government.[73]

Collectively, the Bambara, Soninké, Khassonké, and Malinké (also called Mandinka), all part of the broader Mandé group, constitute 50 percent of Mali's population.[58] Other significant groups are the Fula (French: Peul; Fula: Fulɓe) (17 percent), Voltaic (12 percent), Songhai (6 percent), and Tuareg and Moor (10 percent).[58]

In the far north, there is a division between Berber-descendent Tuareg nomad populations and the darker-skinned Bella or Tamasheq people, due the historical spread of slavery in the region. An estimated 800,000 people in Mali are descended from slaves.[27] Slavery in Mali has persisted for centuries.[74] The Arabic population kept slaves well into the 20th century, until slavery was suppressed by French authorities around the mid-20th century. There still persist certain hereditary servitude relationships,[75][76] and according to some estimates, even today approximately 200,000 Malians are still enslaved.[77]

Although Mali has enjoyed a reasonably good inter-ethnic relationships based on the long history of coexistence, some hereditary servitude and bondage relationship exist, as well as ethnic tension between settled Songhai and nomadic Tuaregs of the north.[71] Due to a backlash against the northern population after independence, Mali is now in a situation where both groups complain about discrimination on the part of the other group.[78] This conflict also plays a role in the continuing Northern Mali conflict where there is a tension between both Tuaregs and the Malian government, and the Tuaregs and radical Islamists who are trying to establish sharia law.[79]

Religion

.jpg)

Islam was introduced to West Africa in the 11th century and remains the predominant religion in much of the region. An estimated 90 percent of Malians are Muslim (mostly Sunni and Ahmadiyya[81]), approximately 5 percent are Christian (about two-thirds Roman Catholic and one-third Protestant) and the remaining 5 percent adhere to indigenous or traditional animist beliefs.[80] Atheism and agnosticism are believed to be rare among Malians, most of whom practice their religion on a daily basis.[82]

The constitution establishes a secular state and provides for freedom of religion, and the government largely respects this right.[82]

Islam as historically practiced in Mali has been moderate, tolerant, and adapted to local conditions; relations between Muslims and practitioners of minority religious faiths have generally been amicable.[82] After the 2012 imposition of sharia rule in northern parts of the country, however, Mali came to be listed high (number 7) in the Christian persecution index published by Open Doors, which described the persecution in the north as severe.[83][84]

Education

Public education in Mali is in principle provided free of charge and is compulsory for nine years between the ages of seven and sixteen.[82] The system encompasses six years of primary education beginning at age 7, followed by six years of secondary education.[82] Mali's actual primary school enrollment rate is low, in large part because families are unable to cover the cost of uniforms, books, supplies, and other fees required to attend.[82]

In the 2000–01 school year, the primary school enrollment rate was 61 percent (71 percent of males and 51 percent of females). In the late 1990s, the secondary school enrollment rate was 15 percent (20 percent of males and 10 percent of females).[82] The education system is plagued by a lack of schools in rural areas, as well as shortages of teachers and materials.[82]

Estimates of literacy rates in Mali range from 27–30 to 46.4 percent, with literacy rates significantly lower among women than men.[82] The University of Bamako, which includes four constituent universities, is the largest university in the country and enrolls approximately 60,000 undergraduate and graduate students.[85]

Health

Mali faces numerous health challenges related to poverty, malnutrition, and inadequate hygiene and sanitation.[82] Mali's health and development indicators rank among the worst in the world.[82] Life expectancy at birth is estimated to be 53.06 years in 2012.[86] In 2000, 62–65 percent of the population was estimated to have access to safe drinking water and only 69 percent to sanitation services of some kind.[82] In 2001, the general government expenditures on health totalled about US$4 per capita at an average exchange rate.[87]

Efforts have been made to improve nutrition, and reduce associated health problems, by encouraging women to make nutritious versions of local recipes. For example, the International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics (ICRISAT) and the Aga Khan Foundation, trained women's groups to make equinut, a healthy and nutritional version of the traditional recipe di-dèguè (comprising peanut paste, honey and millet or rice flour). The aim was to boost nutrition and livelihoods by producing a product that women could make and sell, and which would be accepted by the local community because of its local heritage.[88]

Medical facilities in Mali are very limited, and medicines are in short supply.[87] Malaria and other arthropod-borne diseases are prevalent in Mali, as are a number of infectious diseases such as cholera and tuberculosis.[87] Mali's population also suffers from a high rate of child malnutrition and a low rate of immunization.[87] An estimated 1.9 percent of the adult and children population was afflicted with HIV/AIDS that year, among the lowest rates in Sub-Saharan Africa.[87] An estimated 85–91 percent of Mali's girls and women have had female genital mutilation (2006 and 2001 data).[89][90]

Culture

.jpg)

The varied everyday culture of Malians reflects the country's ethnic and geographic diversity.[91] Most Malians wear flowing, colorful robes called boubous that are typical of West Africa. Malians frequently participate in traditional festivals, dances, and ceremonies.[91]

Music

Malian musical traditions are derived from the griots, who are known as "Keepers of Memories".[92] Malian music is diverse and has several different genres. Some famous Malian influences in music are kora virtuoso musician Toumani Diabaté, the late roots and blues guitarist Ali Farka Touré, the Tuareg band Tinariwen, and several Afro-pop artists such as Salif Keita, the duo Amadou et Mariam, Oumou Sangare, and Habib Koité. Dance also plays a large role in Malian culture.[93] Dance parties are common events among friends, and traditional mask dances are performed at ceremonial events.[93]

Literature

Though Mali's literature is less famous than its music,[94] Mali has always been one of Africa's liveliest intellectual centers.[95] Mali's literary tradition is passed mainly by word of mouth, with jalis reciting or singing histories and stories known by heart.[95][96] Amadou Hampâté Bâ, Mali's best-known historian, spent much of his life writing these oral traditions down for the world to remember.[96]

The best-known novel by a Malian writer is Yambo Ouologuem's Le devoir de violence, which won the 1968 Prix Renaudot but whose legacy was marred by accusations of plagiarism.[95][96] Other well-known Malian writers include Baba Traoré, Modibo Sounkalo Keita, Massa Makan Diabaté, Moussa Konaté, and Fily Dabo Sissoko.[95][96]

Sport

The most popular sport in Mali is football (soccer),[97][98] which became more prominent after Mali hosted the 2002 African Cup of Nations.[97][99] Most towns and cities have regular games;[99] the most popular teams nationally are Djoliba AC, Stade Malien, and Real Bamako, all based in the capital.[98] Informal games are often played by youths using a bundle of rags as a ball.[98]

Basketball is another major sport;[98][100] the Mali women's national basketball team, led by Hamchetou Maiga, competed at the 2008 Beijing Olympics.[101] Traditional wrestling (la lutte) is also somewhat common, though popularity has declined in recent years.[99] The game wari, a mancala variant, is a common pastime.[98]

Cuisine

Rice and millet are the staples of Malian cuisine, which is heavily based on cereal grains.[102][103] Grains are generally prepared with sauces made from edible leaves, such as spinach or baobab, with tomato peanut sauce, and may be accompanied by pieces of grilled meat (typically chicken, mutton, beef, or goat).[102][103] Malian cuisine varies regionally.[102][103] Other popular dishes include fufu, jollof rice, and maafe.

Media

In Mali, there are several newspapers such as Les Echos, L'Essor, Info Matin, Nouvel Horizon, and Le Républicain.[104] The Telecommunications in Mali include 869,600 mobile phones, 45,000 televisions and 414,985 internet users.

See also

References

- ↑ Presidency of Mali: Symboles de la République, L'Hymne National du Mali. Koulouba.pr.ml. Retrieved 4 May 2012.

- ↑ "Mali preliminary 2009 census". Institut National de la Statistique. Retrieved 12 January 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 "Mali". International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 17 April 2013.

- ↑ "Gini Index". World Bank. Retrieved 2 March 2011.

- ↑ "2014 Human Development Report Summary" (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. 2014. pp. 21–25. Retrieved 27 July 2014.

- ↑ Which side of the road do they drive on? Brian Lucas. August 2005. Retrieved 28 January 2009.

- ↑ Mali gold reserves rise in 2011 alongside price. Retrieved 17 January 2013

- ↑ Human Development Indices, Table 3: Human and income poverty, p. 35. Retrieved 1 June 2009

- ↑ "Chapter 1: Religious Affiliation". The World's Muslims: Unity and Diversity. Pew Research Center's Religion & Public Life Project. 9 August 2012. Retrieved 4 September 2013.

- ↑ Topics. MuslimHeritage.com (5 June 2003). Retrieved 8 October 2012.

- ↑ Sankore University. Muslimmuseum.org. Retrieved 8 October 2012.

- ↑ Mali Empire (ca. 1200- ) | The Black Past: Remembered and Reclaimed. The Black Past. Retrieved 8 October 2012.

- ↑ Lydia Polgreen and Alan Cowell, "Mali Rebels Proclaim Independent State in North", The New York Times (6 April 2012)

- 1 2 UN Security council condemns Mali coup. Telegraph (23 March 2012). Retrieved 24 March 2013.

- ↑ "Mali – la France a mené une série de raids contre les islamistes". Le Monde. 12 January 2013. Retrieved 13 January 2013.

- 1 2 3 Mali country profile, p. 1.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Mali country profile. Mali was later responsible for the collapse of Islamic Slave Army from the North. The defeat of Tukuror Slave Army, was repeated by Mali against the France and Spanish Expeditionary Army in 1800s ("Blanc et memoires"). . p. 2.

- ↑ John Iliffe (2007) Africans: the history of a continent. Cambridge University Press. p. 69. ISBN 0-521-68297-5

- ↑ Core document forming part of the reports of states parties: Mali. United Nations Human Rights Website.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Mali country profile, p. 3.

- ↑ "Mali's nomads face famine". BBC News. 9 August 2005.

- 1 2 http://www.nonviolent-conflict.org/index.php/movements-and-campaigns/movements-and-campaigns-summaries?sobi2Task=sobi2Details&catid=34&sobi2Id=10 Mali March 1991 Revolution

- 1 2 Nesbitt, Katherine. "Mali's March Revolution (1991)". International Center on Nonviolent Conflict. Retrieved 1 March 2012.

- ↑ Bussa, Edward. "Mali's March to Democracy". threadster.com. Retrieved 1 March 2012.

- ↑ Mali country profile, p. 4.

- ↑ USAID Africa: Mali. USAID. Retrieved 15 May 2008. Retrieved 3 June 2008.

- 1 2 Tran, Mark (23 October 2012). "Mali conflict puts freedom of 'slave descendants' in peril". The Guardian (London). Retrieved 24 November 2012.

- ↑ York, Geoffrey (11 November 2012). "Mali chaos gives rise to slavery, persecution". The Globe and Mail (Toronto).

- ↑ Mali clashes force 120 000 from homes. News24 (22 February 2012). Retrieved 23 February 2012.

- ↑ Callimachi, Rukmini (3 April 2012) "Post-coup Mali hit with sanctions by African neighbours". Globe and Mail. Retrieved 4 May 2012.

- ↑ "Tuareg rebels declare independence in north Mali". France 24. 6 April 2012. Retrieved 28 July 2012.

- ↑ Tiemoko Diallo; Adama Diarra (28 June 2012). "Islamists declare full control of Mali's north". Reuters. Retrieved 28 July 2012.

- ↑ "Mali Islamists want sharia not independence". Google News. Agence France-Presse. 20 June 2012. Retrieved 28 July 2012.

- ↑ "French Troops Retake Kidal Airport, Move into City". USA Today. 30 January 2013. Retrieved 30 January 2013. French troops retake the last remaining Islamist urban stronghold in Mali.

- ↑ "Mali conflict: Timbuktu hails French President Hollande". BBC News. 2 February 2013. Retrieved 4 February 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Mali country profile, p. 5.

- ↑ Uranium Mine Ownership – Africa. Wise-uranium.org. Retrieved 24 March 2013.

- ↑ Muller, CJ and Umpire, A (22 November 2012) An Independent Technical Report on the Mineral Resources of Falea Uranium, Copper and Silver Deposit, Mali, West Africa. Minxcon.

- ↑ Uranium in Africa. World-nuclear.org. Retrieved 24 March 2013.

- ↑ Martin, Phillip L. (2006). Managing Migration: The Promise of Cooperation. Lanham, Maryland: Lexington Books. p. 134. ISBN 978-0-7391-1341-7.

- ↑ DiPiazza, p. 37.

- ↑ Loi N°99-035/ Du 10 Aout 1999 Portant Creation des Collectivites Territoriales de Cercles et de Regions (PDF) (in French), Ministère de l'Administration Territoriales et des Collectivités Locales, République du Mali, 1999

- ↑ "Tuareg rebels declare the independence of Azawad, north of Mali". Al Arabiya. 6 April 2012. Retrieved 6 April 2012.

- ↑ Video: US condemns Mali coup amid reports of looting. Telegraph (22 March 2012). Retrieved 24 March 2013.

- ↑ Hossiter, Adam (12 December 2012) Mali’s Prime Minister Resigns After Arrest, Muddling Plans to Retake North. The New York Times

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Mali country profile, p. 14.

- ↑ Constitution of Mali, Art. 30.

- ↑ Constitution of Mali, Art. 29 & 46.

- ↑ Constitution of Mali, Art. 38.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Mali country profile, p. 15.

- ↑ Constitution of Mali, Art. 59 & 61.

- ↑ (French) Koné, Denis. Mali: "Résultats définitifs des Législatives". Les Echos (Bamako) (13 August 2007). Retrieved 24 June 2008.

- ↑ Constitution of Mali, Art. 65.

- ↑ Constitution of Mali, Art. 81.

- ↑ Constitution of Mali, Art. 83–94.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Mali country profile, p. 17.

- ↑ "ion suspends Mali over coup". Al Jazeera. 23 March 2012. Retrieved 23 March 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Central Intelligence Agency (2009). "Mali". The World Factbook. Retrieved 12 January 2010.

- 1 2 Mali country profile, p. 18.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 "Mali". U.S. State Department. May 2008. Retrieved 4 June 2008.

- ↑ Mali and the WTO. World Trade Organization. Retrieved 24 March 2013.

- ↑ "OHADA.com: The business law portal in Africa". Retrieved 22 March 2009.

- ↑ Mali country profile, p. 9.

- ↑ Zone franc sur le site de la Banque de France. Banque-france.fr. Retrieved 24 March 2013.

- 1 2 3 Hale, Briony (13 May 1998). "Mali's Golden Hope". BBC News. Retrieved 4 June 2008.

- 1 2 3 4 Cavendish, Marshall (2007). World and Its Peoples: Middle East, Western Asia, and Northern Africa. Tarrytown, New York: Marshall Cavendish. p. 1367. ISBN 978-0-7614-7571-2.

- ↑ May, Jacques Meyer (1968). The Ecology of Malnutrition in the French Speaking Countries of West Africa and Madagascar. New York: Macmillan Publishing Company. p. 291. ISBN 978-0-02-848960-5.

- ↑ Campbell, Bonnie (2004). Regulating Mining in Africa: For Whose Benefit?. Uppsala, Sweden: Nordic African Institute. p. 43. ISBN 978-0-7614-7571-2.

- ↑ African Development Bank, p. 186.

- ↑ Farvacque-Vitkovic, Catherine et al. (September 2007) DEVELOPMENT OF THE CITIES OF MALI — Challenges and Priorities. Africa Region Working Paper Series No. 104/a. World Bank

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Mali country profile, p. 6.

- ↑ "Mali Demographics Profile 2014".

- ↑ http://www.tlfq.ulaval.ca/axl/afrique/mali.htm

- ↑ Fortin, Jacey (16 January 2013). "Mali's Other Crisis: Slavery Still Plagues Mali, And Insurgency Could Make It Worse". International Business Times.

- ↑ "Kayaking to Timbuktu, Writer Sees Slave Trade". National Geographic News. 5 December 2002.

- ↑ "Kayaking to Timbuktu, Original National Geographic Adventure Article discussing Slavery in Mali". National Geographic Adventure. December 2002/January 2003.

- ↑ MacInnes-Rae, Rick (26 November 2012). "Al-Qaeda complicating anti-slavery drive in Mali". CBC News.

- ↑ Bruce S. Hall, A History of Race in Muslim West Africa, 1600–1960. Cambridge University Press, 2011, ISBN 9781107002876: "The mobilization of local ideas about racial difference has been important in generating, and intensifying, civil wars that have occurred since the end of colonial rule in all of the countries that straddle the southern edge of the Sahara Desert. [...] contemporary conflicts often hearken back to an older history in which blackness could be equated with slavery and non-blackness with predatory and uncivilized banditry." (cover text)

- ↑ see e.g. Mali's conflict and a 'war over skin colour', Afua Hirsch, The Guardian, Friday 6 July 2012.

- 1 2 International Religious Freedom Report 2008: Mali. State.gov (19 September 2008). Retrieved 4 May 2012.

- ↑ "The World's Muslims: Unity and Diversity" (PDF). Pew Forum on Religious & Public life. 9 August 2012. Retrieved 2 June 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Mali country profile, p. 7.

- ↑ Report points to 100 million persecuted Christians.. Retrieved 10 January 2013.

- ↑ OPEN DOORS World Watch list 2012. Worldwatchlist.us. Retrieved 24 March 2013.

- ↑ "Université de Bamako – Bamako, Mali". Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine. Retrieved 8 July 2013.

- ↑ CIA World Factbook: Life Expectancy ranks

- 1 2 3 4 5 Mali country profile, p. 8.

- ↑ Nourishing communities through holistic farming, Impatient optimists, Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. 30 April 2013.

- ↑ WHO | Female genital mutilation and other harmful practices. Who.int (6 May 2011). Retrieved 4 May 2012.

- ↑ Female genital cutting in the Demographic Health Surveys: a critical and comparative analysis. Calverton, MD: ORC Marco; 2004 (DHS Comparative Reports No. 7). (PDF). Retrieved 18 January 2013.

- 1 2 Pye-Smith, Charlie & Rhéal Drisdelle. Mali: A Prospect of Peace? Oxfam (1997). ISBN 0-85598-334-5, p. 13.

- ↑ Crabill, Michelle and Tiso, Bruce (January 2003). Mali Resource Website. Fairfax County Public Schools. Retrieved 4 June 2008.

- 1 2 "Music". Embassy of the Republic of Mali in Japan. Retrieved 8 July 2013.

- ↑ Velton, p. 29.

- 1 2 3 4 Milet, p. 128.

- 1 2 3 4 Velton, p. 28.

- 1 2 Milet, p. 151.

- 1 2 3 4 5 DiPiazza, p. 55.

- 1 2 3 Hudgens, Jim, Richard Trillo, and Nathalie Calonnec. The Rough Guide to West Africa. Rough Guides (2003). ISBN 1-84353-118-6, p. 320.

- ↑ "Malian Men Basketball". Africabasket.com. Retrieved 3 June 2008.

- ↑ Chitunda, Julio. "Ruiz looks to strengthen Mali roster ahead of Beijing". FIBA.com (13 March 2008). Retrieved 24 June 2008.

- 1 2 3 Velton, p. 30.

- 1 2 3 Milet, p. 146.

- ↑ Murison, Katharine, ed. (2002). Africa South of the Sahara 2003. Taylor & Francis. pp. 652–53. ISBN 978-1-85743-131-5.

Bibliography

- "Constitution of Mali" (PDF) (in French). A student-translated English version is also available.

- DiPiazza, Francesca Davis (2006). Mali in Pictures. Minneapolis, Minnesota: Learner Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-8225-6591-8.

- "Mali country profile" (PDF). Library of Congress Federal Research Division. January 2005. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- Milet, Eric and Manaud, Jean-Luc (2007). Mali (in French). Editions Olizane. ISBN 2-88086-351-1.

- Velton, Ross (2004). Mali. Bradt Travel Guides. ISBN 1-84162-077-7.

External links

![]() Wikimedia Atlas of Mali

Wikimedia Atlas of Mali

![]() Mali travel guide from Wikivoyage

Mali travel guide from Wikivoyage

- Official website

- Mali entry at The World Factbook

- The European Union mission in Mali – Hungary's involvement in the mission

- War at the background of Europe: The crisis of Mali

- Mali from UCB Libraries GovPubs

- Mali at DMOZ

- Mali profile from the BBC News

- Trade

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

.svg.png)

.svg.png)