Buprenorphine

| |

| |

| Systematic (IUPAC) name | |

|---|---|

|

(2S)-2-[(5R,6R,7R,14S)-9α-cyclopropylmethyl-4,5-epoxy-6,14-ethano-3-hydroxy-6-methoxymorphinan-7-yl]-3,3-dimethylbutan-2-ol | |

| Clinical data | |

| Trade names | Buprenex, Subutex, Suboxone, Butrans, Cizdol, Zubsolv |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a605002 |

| Pregnancy category | |

| Legal status |

|

| Routes of administration | sublingual, IM, IV, transdermal, intranasal, rectally, orally. |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 30%(sublingual)[1]/48.2±8.35%(intranasal)[2] |

| Protein binding | 96% |

| Metabolism |

hepatic CYP3A4, CYP2C8 |

| Biological half-life | 20–70, mean 37 hours |

| Excretion | biliary and renal |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number |

52485-79-7 |

| ATC code | N02AE01 N07BC01 |

| PubChem | CID 644073 |

| IUPHAR/BPS | 1670 |

| DrugBank |

DB00921 |

| ChemSpider |

559124 |

| UNII |

40D3SCR4GZ |

| KEGG |

D07132 |

| ChEBI |

CHEBI:3216 |

| ChEMBL |

CHEMBL511142 |

| Chemical data | |

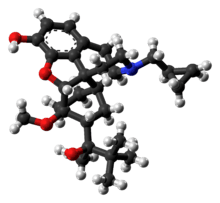

| Formula | C29H41NO4 |

| Molar mass | 467.64 g/mol |

| |

| |

| | |

Buprenorphine is a semisynthetic opioid derivative of thebaine. It is a mixed partial agonist opioid receptor modulator that is used to treat opioid addiction in higher dosages, to control moderate acute pain in non-opioid-tolerant individuals in lower dosages and to control moderate chronic pain in even smaller doses.[3] It is available in a variety of formulations: Cizdol, Subutex, Suboxone, Zubsolv, Bunavail (available as buprenorphine HCl alone or buprenorphine and naloxone HCl (see buprenorphine/naloxone); typically used for opioid addiction), Temgesic (sublingual tablets for moderate to severe pain), Buprenex (solutions for injection often used for acute pain in primary-care settings), Norspan and Butrans (transdermal preparations used for chronic pain).[4]

Medical uses

Its primary uses in medicine are in the treatment of those addicted to opioids, such as heroin and oxycodone, but it may also be used to treat pain, and sometimes nausea in antiemetic intolerant individuals, most often in transdermal patch form.[3]

Treatment of opioid addiction

Buprenorphine versus methadone

Both buprenorphine and methadone are medications used for detoxification, short- and long-term opioid replacement therapy. Buprenorphine has the advantage of being only a partial agonist; hence negating the potential for life-threatening respiratory depression in cases of abuse.[4] Studies show the effectiveness of buprenorphine and methadone are almost identical, and largely share adverse-effect profiles apart from more sedation among methadone users. At low doses from 2 to 6 mg, however, buprenorphine has a lower retention rate than low doses from 40 mg or less of methadone.[5]

Inpatient rehabilitation and detoxification

Rehabilitation programs consist of "detox" and "treatment" phases. The detoxification ("detox") phase consists of medically supervised withdrawal from the drug of dependency on to buprenorphine, sometimes aided by the use of medications such as benzodiazepines like oxazepam or diazepam (modern milder tranquilizers that assist with anxiety, sleep, and muscle relaxation), clonidine (a blood-pressure medication that may reduce some opioid withdrawal symptoms), and anti-inflammatory/pain relief drugs such as ibuprofen and aspirin.

The treatment phase begins once the person is stabilized and receives medical clearance. This portion of treatment consists of multiple therapy sessions, which include both group and individual counseling with various chemical dependency counselors, psychologists, psychiatrists, social workers, and other professionals. In addition, many treatment centers utilize twelve-step facilitation techniques, embracing the 12-step programs practiced by such organizations as Alcoholics Anonymous and Narcotics Anonymous. Some people on maintenance therapies have veered away from such organizations as Narcotics Anonymous, instead opting to create their own twelve-step fellowships (such as Methadone Anonymous) or depart entirely from the twelve-step model of recovery (using a program such as SMART Recovery).[6][7]

Suboxone and naloxone

Suboxone (a controlled substance) contains buprenorphine as well as the opioid antagonist naloxone to deter the use of tablets by intravenous injection. Even though controlled trials in human subjects suggest that buprenorphine and naloxone at a 4:1 ratio will produce unpleasant withdrawal symptoms if taken intravenously by people who are addicted to opioids, these studies administered buprenorphine/naloxone to people already addicted to less powerful opiates such as morphine.[8][9][10][11][12] These studies show the strength of buprenorphine/naloxone in displacing opiates, but do not show the effectiveness of naloxone displacing buprenorphine and causing withdrawal. The Suboxone formulation still has potential to produce an opioid agonist "high" if injected by non-dependent persons, which may provide some explanation to street reports indicating that the naloxone is an insufficient deterrent to injection of suboxone.[13][14] The addition of naloxone and the reasons for it are conflicting. Published data show that the μ opioid receptor binding affinity of buprenorphine is higher than naloxone's (Ki = 0.2157 nM for buprenorphine, Ki = 1.1518 nM for naloxone; smaller Ki mean higher affinity).[15] Furthermore, the IC50 or the half maximal inhibitory concentration for buprenorphine to displace naloxone is 0.52 nM, while the IC50s of other opiates in displacing buprenorphine, is 100 to 1,000 times greater.[16] These studies help explain the ineffectiveness of naloxone in preventing suboxone abuse, as well as the potential dangers of overdosing on buprenorphine, since a continuous infusion of naloxone can be necessary in order to reverse its respiratory effects.[17]

Butrans for chronic pain relief

Butrans Transdermal Patch System is available in 5 mcg/hour, 7.5 mcg/hour, 10 mcg/hour, 15 mcg/hour, and 20 mcg/hour doses. Each patch is applied for 7 days of around-the-clock management of moderate to severe chronic pain. It is not indicated for use in acute pain, pain that is expected to last only for a short period of time, or post-operative pain. Nor is it indicated or recommended for use in the treatment of opioid addiction. [18]

Investigational uses

Depression

A clinical trial conducted at Harvard Medical School in the mid-1990s demonstrated that a majority of persons with non‑psychotic unipolar depression who were refractory to conventional antidepressants and electroconvulsive therapy could be successfully treated with buprenorphine.[19][20][21][22][23][24][25] Clinical depression is currently not an approved indication for the use of any opioid, but some doctors are realizing buprenorphine's potential as an antidepressant when the affected person cannot tolerate or is resistant to conventional antidepressant therapies.

ALKS-5461, a combination product of buprenorphine and samidorphan (a selective μ-opioid receptor antagonist), is currently undergoing phase III clinical trials in the United States for augmentation of antidepressant therapy for treatment-resistant depression.[26]

Neonatal abstinence

Buprenorphine has been used in the treatment of the neonatal abstinence syndrome,[27] a condition in which newborns exposed to opioids during pregnancy demonstrate signs of withdrawal.[28] Use currently is limited to infants enrolled in a clinical trial conducted under an FDA approved investigational new drug (IND) application.[29] An ethanolic formulation used in neonates is stable at room temperature for at least 30 days.[30]

History

In 1969, researchers at Reckitt & Colman (now Reckitt Benckiser) had spent 10 years attempting to synthesize an opioid compound "with structures substantially more complex than morphine [that] could retain the desirable actions whilst shedding the undesirable side effects (addiction)." Although the drug is physically addictive when used as prescribed. Reckitt found success when researchers synthesized RX6029 which had showed success in reducing dependence in test animals. RX6029 was named buprenorphine and began trials on humans in 1971.[31][32] By 1978 buprenorphine was first launched in the UK as an injection to treat severe pain, with a sublingual formulation released in 1982.

Regulation

In the United States, buprenorphine (Subutex) and buprenorphine with naloxone (Suboxone) were approved for opioid addiction by the United States Food and Drug Administration in October 2002.[33] It was rescheduled to Schedule III drug from Schedule V just before FDA approval of Subutex and Suboxone. In the years prior to Suboxone's approval, Reckitt Benckiser had lobbied Congress to help craft the Drug Addiction Treatment Act of 2000 (DATA 2000), which gave authority to the Secretary of Health and Human Services to grant a waiver to physicians with certain training to prescribe and administer Schedule III, IV, or V narcotic drugs for the treatment of addiction or detoxification. Prior to the passage of this law, such treatment was not permitted in outpatient settings except for clinics designed specifically for drug addiction.[34]

The waiver, which can be granted after the completion of an eight-hour course, is required for outpatient treatment of opioid addiction with Subutex and Suboxone. Initially, the number of patients each approved physician could treat was limited to ten. This was eventually modified to allow approved physicians to treat up to a hundred patients with buprenorphine for opioid addiction in an outpatient setting.[35] Due to this patient limit and the requisite eight-hour training course, many addicts find it very difficult to get a prescription, despite the drug's effectiveness.[36]

In the European Union, Subutex and Suboxone, buprenorphine's high-dose sublingual tablet preparations, were approved for opioid addiction treatment in September 2006.[37] In the Netherlands, buprenorphine is a List II drug of the Opium Law, though special rules and guidelines apply to its prescription and dispensation.

In recent years, buprenorphine has been introduced in most European countries as a transdermal formulation (marketed as Transtec) for the treatment of chronic pain not responding to non-opioids.

Pharmacodynamics

Buprenorphine has been reported to possess the following pharmacological activity:[38]

- μ-Opioid receptor (MOR): Ki = 1.5 nM; IA = 28.7%

- κ-Opioid receptor (KOR): Ki = 2.5 nM; IA = 0%

- δ-Opioid receptor (DOR): Ki = 6.1 nM; IA = 0%

- Nociceptin receptor (ORL-1): Ki = 77.4 nM; IA = 15.5%

In simplified terms, buprenorphine can essentially be thought of as a non-selective, mixed agonist–antagonist opioid receptor modulator,[39] acting as a weak partial agonist of the MOR, an antagonist of the KOR, an antagonist of the DOR, and a relatively low-affinity, very weak partial agonist of the ORL-1.[40][41][42][43][44][45]

Buprenorphine is also known to bind to with high affinity and antagonize the putative ε-opioid receptor.[46][47]

Buprenorphine also blocks voltage-gated sodium channels via the local anesthetic binding site, and this underlies its potent local anesthetic properties.[48]

Full analgesic efficacy of buprenorphine requires both exon 11-[49] and exon 1-associated μ-opioid receptor splice variants.[50]

Pharmacokinetics

Buprenorphine is metabolised by the liver, via CYP3A4 (also CYP2C8 seems to be involved) isozymes of the cytochrome P450 enzyme system, into norbuprenorphine (by N-dealkylation). The glucuronidation of buprenorphine is primarily carried out by UGT1A1 and UGT2B7, and that of norbuprenorphine by UGT1A1 and UGT1A3. These glucuronides are then eliminated mainly through excretion into the bile. The elimination half-life of buprenorphine is 20–73 hours (mean 37). Due to the mainly hepatic elimination, there is no risk of accumulation in people with renal impairment.[51]

One of the major active metabolites of buprenorphine is norbuprenorphine, which, contrary to buprenorphine itself, is a full agonist of the MOR, DOR, and ORL-1, and a partial agonist at the KOR.[52][53] However, relative to buprenorphine, norbuprenorphine has extremely little antinociceptive potency (1/50th that of buprenorphine), but markedly depresses respiration (10-fold more than buprenorphine).[54] This can be explained by very poor brain penetration of norbuprenorphine due to a high affinity of the compound for P-glycoprotein.[54] In contrast to norbuprenorphine, buprenorphine and its glucuronide metabolites are negligibly transported by P-glycoprotein.[54]

The glucuronides of buprenorphine and norbuprenorphine are also biologically active, and represent major active metabolites of buprenorphine.[55] Buprenorphine-3-glucuronide has affinity for the MOR (Ki = 4.9 pM), DOR (Ki = 270 nM) and ORL-1 (Ki = 36 µM), and no affinity for the KOR. It has a small antinociceptive effect and no effect on respiration. Norbuprenorphine-3-glucuronide has no affinity for the MOR or DOR, but does bind to the KOR (Ki = 300 nM) and ORL-1 (Ki = 18 µM). It has a sedative effect but no effect on respiration.

Detection in biological fluids

Buprenorphine and norbuprenorphine may be quantitated in blood or urine to monitor use or abuse, confirm a diagnosis of poisoning, or assist in a medicolegal investigation. There is a significant overlap of drug concentrations in body fluids within the possible spectrum of physiological reactions ranging from asymptomatic to comatose. Therefore, it is critical to have knowledge of both the route of administration of the drug and the level of tolerance to opioids of the individual when results are interpreted.[56]

Chemistry

Buprenorphine is a semi-synthetic analogue of thebaine[57] and is fairly soluble in water, as its hydrochloride salt.[4] It also degrades in the presence of light.[4]

Adverse effects

Common adverse drug reactions associated with the use of buprenorphine are similar to those of other opioids and include: nausea and vomiting, drowsiness, dizziness, headache, memory loss, cognitive and neural inhibition, perspiration, itchiness, dry mouth, miosis, orthostatic hypotension, male ejaculatory difficulty, decreased libido, and urinary retention. Constipation and CNS effects are seen less frequently than with morphine.[58] Hepatic necrosis and hepatitis with jaundice have been reported with the use of buprenorphine, especially after intravenous injection of crushed tablets.

Buprenorphine treatment carries the risk of causing psychological and or physical dependence. Buprenorphine has a slow onset, mild effect, and is very long acting with a half-life of 24 to 60 hours.[59]

Unlike methadone, long term use of buprenorphine does not significantly suppress plasma testosterone levels in men and is therefore less frequently related to sexual side effects.[60]

The most severe and serious adverse reaction associated with opioid use in general is respiratory depression, the mechanism behind fatal overdose. Buprenorphine behaves differently than other opioids in this respect, as it shows a ceiling effect for respiratory depression.[58] Moreover, doubts about the antagonisation of the respiratory effects by naloxone have been disproved: Buprenorphine effects can be antagonised with a continuous infusion of naloxone.[61] Concurrent use of buprenorphine with other CNS depressants (such as alcohol or benzodiazepines) is contraindicated as it may lead to fatal respiratory depression. Benzodiazepines, in recommended doses, are not contraindicated in individuals tolerant to either opioids or benzodiazepines.

There is another consequence of high-dose buprenorphine treatment that often goes overlooked by both physicians and patients when electing to use buprenorphine (in the form of Butrans transdermal patches) for chronic pain management. Because buprenorphine binds so tightly to μ‑opioid receptors in the central nervous system, it takes an extremely large dose of potent opioid pain medication to displace the buprenorphine from those receptors and provide additional pain relief in the acute setting. Patients on high-dose buprenorphine therapy may be unaffected by even very large doses of potent opioids such as fentanyl, morphine, or hydromorphone. Sufentanil (trade name Sufenta) is an extremely potent opioid analgesic (5 to 10 times more potent than fentanyl and 500 times more potent than morphine) for use in specific surgeries and surgery in highly opioid-tolerant or opioid-dependent patients that has a binding affinity that is high enough to theoretically break through a "buprenorphine blockade" to provide pain relief in patients taking high-dose buprenorphine. The problem is that sufentanil is frequently not available in the emergency room or acute care setting because of its highly specialized indications, thus making it very problematic for acute care practitioners to manage severe acute pain in persons already taking high-dose buprenorphine.[4] It is also difficult to achieve acute opioid analgesia in persons using buprenorphine for opioid replacement therapy.[62] Here, fentanyl, which has a higher affinity for μ‑opioid receptors, can successfully overcome buprenorphine blockade.[63] Fentanyl is widely available in acute care settings.[64]

See also

- 18,19-Dehydrobuprenorphine

- 6,14-Endoethenotetrahydrooripavine

- Butorphanol

- Ciramadol

- Dezocine

- Ibogaine

- Nalbuphine

- Naltrexone

- Low-dose naltrexone

- Pentazocine

- Profadol

- Thienorphine

- Xorphanol

References

- ↑ Mendelson J, Upton RA, Everhart ET, Jacob P 3rd, Jones RT. (1997). "Bioavailability of sublingual buprenorphine.". Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 37 (1): 31–7. doi:10.1177/009127009703700106. PMID 9048270.

- ↑ Eriksen J, Jensen NH, Kamp-Jensen M, Bjarnø H, Friis P, Brewster D (1989). "The systemic availability of buprenorphine administered by nasal spray". J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 41 (11): 803–5. doi:10.1111/j.2042-7158.1989.tb06374.x. PMID 2576057.

- 1 2 Rossi, S, ed. (2013). Australian Medicines Handbook (2013 ed.). Adelaide: The Australian Medicines Handbook Unit Trust. ISBN 978-0-9805790-9-3.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Buprenorphine". Martindale: The Complete Drug Reference. London, UK: Pharmaceutical Press. 14 January 2014. Retrieved 6 April 2014.

- ↑ Mattick RP, Kimber J, Breen C, Davoli M (2008). "Buprenorphine maintenance versus placebo or methadone maintenance for opioid dependence". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (2): CD002207. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002207.pub3. PMID 18425880.

- ↑ Glickman L, Galanter M, Dermatis H, Dingle S (December 2006). "Recovery and spiritual transformation among peer leaders of a modified methadone anonymous group". J Psychoactive Drugs 38 (4): 531–3. doi:10.1080/02791072.2006.10400592. PMID 17373569.

Gilman SM, Galanter M, Dermatis H (December 2001). "Methadone Anonymous: A 12-Step Program for Methadone Maintained Heroin Addicts". Subst Abus 22 (4): 247–256. doi:10.1080/08897070109511466. PMID 12466684.

McGonagle D (October 1994). "Methadone anonymous: a 12-step program. Reducing the stigma of methadone use". J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv 32 (10): 5–12. PMID 7844771. - ↑ Horvath AT (2000). Journal of Rational-Emotive and Cognitive-Behavior Therapy 18 (3): 181–191. doi:10.1023/A:1007831005098. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Mendelson J, Jones RT, Fernandez I, Welm S, Melby AK, Baggott MJ (1996). "Buprenorphine and naloxone interactions in opiate-dependent volunteers*". Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics 60 (1): 105–114. doi:10.1016/S0009-9236(96)90173-3. PMID 8689806.

- ↑ Fudala PJ, Yu E, Macfadden W, Boardman C, Chiang CN (1998). "Effects of buprenorphine and naloxone in morphine-stabilized opioid addicts". Drug and Alcohol Dependence 50 (1): 1–8. doi:10.1016/S0376-8716(98)00008-8. PMID 9589267.

- ↑ Stoller KB, Bigelow GE, Walsh SL, Strain EC (2001). "Effects of buprenorphine/naloxone in opioid-dependent humans". Psychopharmacology 154 (3): 230–242. doi:10.1007/s002130000637. PMID 11351930.

- ↑ Strain EC, Preston KL, Liebson IA, Bigelow GE (1992). "Acute effects of buprenorphine, hydromorphone and naloxone in methadone-maintained volunteers". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics 261 (3): 985–993. PMID 1376362.

- ↑ Harris DS, Jones RT, Welm S, Upton RA, Lin E, Mendelson J (2000). "Buprenorphine and naloxone co-administration in opiate-dependent patients stabilized on sublingual buprenorphine". Drug and Alcohol Dependence 61 (1): 85–94. doi:10.1016/S0376-8716(00)00126-5. PMID 11064186.

- ↑ Strain EC, Stoller K, Walsh SL, Bigelow GE (2000). "Effects of buprenorphine versus buprenorphine/naloxone tablets in non-dependent opioid abusers". Psychopharmacology 148 (4): 374–383. doi:10.1007/s002130050066. PMID 10928310.

- ↑ Clinical Guidelines for the Use of Buprenorphine in the Treatment of Opioid Addiction. Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) 40. Laura McNicholas. US Department of Health and Human Services.

- ↑ Volpe DA, McMahon Tobin GA, Mellon RD, Katki AG, Parker RJ, Colatsky T, Kropp TJ, Verbois SL (2011). "Uniform assessment and ranking of opioid Mu receptor binding constants for selected opioid drugs". Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology 59 (3): 385–390. doi:10.1016/j.yrtph.2010.12.007. PMID 21215785.

- ↑ Villiger JW, Taylor KM (1981). "Buprenorphine : Characteristics of binding sites in the rat central nervous system". Life Sciences 29 (26): 2699–2708. doi:10.1016/0024-3205(81)90529-4. PMID 6276633.

- ↑ Dahan A. (2006). "Opioid-induced respiratory effects: new data on buprenorphine.". Palliative medicine. 20 Suppl 1: s3–8. PMID 16764215.

- ↑ "Butrans Medication Guide". Butrans Medication Guide. Purdue Pharma L.P. Retrieved 7 July 2014.

- ↑ Bodkin JA, Zornberg GL, Lukas SE, Cole JO (1995). "Buprenorphine treatment of refractory depression". Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology 15 (1): 49–57. doi:10.1097/00004714-199502000-00008. PMID 7714228.

- ↑ Emrich HM, Vogt P, Herz A (1982). "Possible antidepressive effects of opioids: Action of buprenorphine". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 398: 108–112. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1982.tb39483.x. PMID 6760767.

- ↑ Emrich HM (1984). "Endorphins in psychiatry". Psychiatr Dev 2 (2): 97–114. PMID 6091098.

- ↑ Mongan L, Callaway E (1990). "Buprenorphine responders". BiolPsychiatry 28 (12): 1078–1080. doi:10.1016/0006-3223(90)90619-d. PMID 2289007.

- ↑ Nyhuis PW, Gastpar M (2005). "Opiate treatment in ECT-resistant depression". Pharmacopsychiatry 38 (5). doi:10.1055/s-2005-918797.

- ↑ Nyhuis PW, Specka M, Gastpar M (2006). "Does the antidepressive response to opiate treatment describe a subtype of depression?". European Neuropsychopharmacology 16 (S16): S309. doi:10.1016/S0924-977X(06)70328-5. Retrieved 21 September 2012.

- ↑ Nyhuis PW, Gastpar M, Scherbaum N (2008). "Opiate Treatment in Depression Refractory to Antidepressants and Electroconvulsive Therapy". Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology 28 (5): 593–595. doi:10.1097/JCP.0b013e31818638a4. PMID 18794671.

- ↑ Alkermes (2014). "Alkermes Announces Initiation of FORWARD-3 and FORWARD-4 Efficacy Studies in Pivotal Program for ALKS 5461 for Treatment of Major Depressive Disorder".

- ↑ Kraft WK, Gibson E, Dysart K, Damle VS, Larusso JL, Greenspan JS, Moody DE, Kaltenbach K, Ehrlich ME (September 2008). "Sublingual buprenorphine for treatment of neonatal abstinence syndrome: a randomized trial". Pediatrics 122 (3): e601–7. doi:10.1542/peds.2008-0571. PMC 2574639. PMID 18694901.

- ↑ Kraft WK, van den Anker JN (2012). "Pharmacologic Management of the Opioid Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome". Pediatric Clinics of North America 59 (5): 1147–1165. doi:10.1016/j.pcl.2012.07.006. PMC 4709246. PMID 23036249.

- ↑ Buprenorphine for the Treatment of Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome. Clinicaltrials.gov. NCT00521248. Retrieved on 2013-05-19.

- ↑ Anagnostis EA, Sadaka RE, Sailor LA, Moody DE, Dysart KC, Kraft WK (2011). "Formulation of buprenorphine for sublingual use in neonates". The journal of pediatric pharmacology and therapeutics : JPPT : the official journal of PPAG 16 (4): 281–284. doi:10.5863/1551-6776-16.4.281 (inactive 2016-02-05). PMC 3385042. PMID 22768012.

- ↑ Campbell N. D., Lovell A. M. (2012). "The history of the development of buprenorphine as an addiction therapeutic". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1248: 124–139. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06352.x. PMID 22256949.

- ↑ Louis S. Harris, ed. (1998). Problems of Drug Dependence, 1998: Proceedings of the 66th Annual Scientific Meeting, The College on Problems of Drug Dependence, Inc. (PDF). NIDA Research Monograph 179.

- ↑ Subutex and Suboxone Approval Letter

- ↑ "Drug Addiction Treatment Act of 2000". SAMHSA, U.S. Department of Health & Human Services.

- ↑ The National Alliance of Advocates for Buprenorphine Treatment. naabt.org. Retrieved on 2013-05-19.

- ↑ Practically a book review: Dying to be Free. Slate Star Codex. Retrieved June 2015

- ↑ Suboxone EU Approval

- ↑ Khroyan TV, Wu J, Polgar WE; et al. (June 2014). "BU08073 a Buprenorphine Analog with Partial Agonist Activity at mu Receptors in vitro but Long-Lasting Opioid Antagonist Activity in vivo in Mice". Br. J. Pharmacol. 172 (2): 668–680. doi:10.1111/bph.12796. PMC 4292977. PMID 24903063.

- ↑ Jacob JJ, Michaud GM, Tremblay EC (1979). "Mixed agonist-antagonist opiates and physical dependence". Br J Clin Pharmacol. 7 Suppl 3: 291S–296S. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.1979.tb04703.x. PMC 1429306. PMID 572694.

- ↑ Lutfy K, Cowan A (October 2004). "Buprenorphine: a unique drug with complex pharmacology". Curr Neuropharmacol 2 (4): 395–402. doi:10.2174/1570159043359477. PMC 2581407. PMID 18997874.

- ↑ Kress HG (March 2009). "Clinical update on the pharmacology, efficacy and safety of transdermal buprenorphine". Eur J Pain 13 (3): 219–30. doi:10.1016/j.ejpain.2008.04.011. PMID 18567516.

- ↑ Robinson SE (2002). "Buprenorphine: an analgesic with an expanding role in the treatment of opioid addiction". CNS Drug Rev 8 (4): 377–90. PMID 12481193.

- ↑ Pedro Ruiz; Eric C. Strain (2011). Lowinson and Ruiz's Substance Abuse: A Comprehensive Textbook. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 439. ISBN 978-1-60547-277-5.

- ↑ Bidlack JM (2014). "Mixed kappa/mu partial opioid agonists as potential treatments for cocaine dependence". Adv. Pharmacol. Advances in Pharmacology 69: 387–418. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-420118-7.00010-X. ISBN 9780124201187. PMID 24484983.

- ↑ Ehrich, Elliot; Turncliff, Ryan; Du, Yangchun; Leigh-Pemberton, Richard; Fernandez, Emilio; Jones, Reese; Fava, Maurizio (2014). "Evaluation of Opioid Modulation in Major Depressive Disorder". Neuropsychopharmacology 40 (6): 1448. doi:10.1038/npp.2014.330. ISSN 0893-133X. PMID 25518754.

- ↑ Mizoguchi H, Wu HE, Narita M; et al. (2002). "Antagonistic property of buprenorphine for putative epsilon-opioid receptor-mediated G-protein activation by beta-endorphin in pons/medulla of the mu-opioid receptor knockout mouse". Neuroscience 115 (3): 715–21. doi:10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00486-4. PMID 12435410.

- ↑ Mizoguchi H, Spaulding A, Leitermann R, Wu HE, Nagase H, Tseng LF (July 2003). "Buprenorphine blocks epsilon- and micro-opioid receptor-mediated antinociception in the mouse". J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 306 (1): 394–400. doi:10.1124/jpet.103.048835. PMID 12721333.

- ↑ Leffler A, Frank G, Kistner K; et al. (June 2012). "Local anesthetic-like inhibition of voltage-gated Na(+) channels by the partial μ-opioid receptor agonist buprenorphine". Anesthesiology 116 (6): 1335–46. doi:10.1097/ALN.0b013e3182557917. PMID 22504149.

- ↑ Xu J, Xu M, Hurd YL, Pasternak GW, Pan YX (2009). "Isolation and characterization of new exon 11-associated N-terminal splice variants of the human mu opioid receptor gene". J. Neurochem. 108 (4): 962–72. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05833.x. PMC 2727151. PMID 19077058.

- ↑ Grinnell S et al (2014): Buprenorphine analgesia requires exon 11-associated mu opioid receptor splice variants. The FASEB Journal

- ↑ Moody DE, Fang WB, Lin SN, Weyant DM, Strom SC, Omiecinski CJ (2009). "Effect of Rifampin and Nelfinavir on the Metabolism of Methadone and Buprenorphine in Primary Cultures of Human Hepatocytes". Drug Metabolism and Disposition 37 (12): 2323–2329. doi:10.1124/dmd.109.028605. PMC 2784702. PMID 19773542.

- ↑ Yassen A, Kan J, Olofsen E, Suidgeest E, Dahan A, Danhof M (2007). "Pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic modeling of the respiratory depressant effect of norbuprenorphine in rats". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics 321 (2): 598–607. doi:10.1124/jpet.106.115972. PMID 17283225.

- ↑ Huang P, Kehner GB, Cowan A, Liu-Chen LY (2001). "Comparison of pharmacological activities of buprenorphine and norbuprenorphine: Norbuprenorphine is a potent opioid agonist". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics 297 (2): 688–695. PMID 11303059.

- 1 2 3 Brown SM, Campbell SD, Crafford A, Regina KJ, Holtzman MJ, Kharasch ED (October 2012). "P-glycoprotein is a major determinant of norbuprenorphine brain exposure and antinociception". J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 343 (1): 53–61. doi:10.1124/jpet.112.193433. PMC 3464040. PMID 22739506.

- ↑ Brown SM, Holtzman M, Kim T, Kharasch ED (2011). "Buprenorphine metabolites, buprenorphine-3-glucuronide and norbuprenorphine-3-glucuronide, are biologically active". Anesthesiology 115 (6): 1251–60. doi:10.1097/ALN.0b013e318238fea0. PMC 3560935. PMID 22037640.

- ↑ Baselt, R. (2008). Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man (8th ed.). Foster City, CA: Biomedical Publications. pp. 190–192. ISBN 0962652377.

- ↑ Heel RC, Brogden RN, Speight TM, Avery GS (February 1979). "Buprenorphine: a review of its pharmacological properties and therapeutic efficacy.". Drugs 17 (2): 81–110. doi:10.2165/00003495-197917020-00001. PMID 378645.

- 1 2 Budd K, Raffa RB. (eds.) Buprenorphine – The unique opioid analgesic. Thieme, 200, ISBN 3-13-134211-0

- ↑ "About Buprenorphine Therapy". Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Retrieved 15 December 2014.

- ↑ Bliesener, N., Albrecht, S., Schwager, A., Weckbecker, K., Lichtermann, D., Klingmuller, D. (17 May 2004). "Plasma Testosterone and Sexual Function in Men Receiving Buprenorphine Maintenance for Opioid Dependence". Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 90 (1): 203–6. doi:10.1210/jc.2004-0929. PMID 15483091.

- ↑ van Dorp E, Yassen A, Sarton E, Romberg R, Olofsen E, Teppema L, Danhof M, Dahan A (2006). "Naloxone reversal of buprenorphine-induced respiratory depression". Anesthesiology 105 (1): 51–7. doi:10.1097/00000542-200607000-00012. PMID 16809994.

- ↑ Alford, Daniel P.; Compton, Peggy; Samet, Jeffrey H. (17 January 2006). "Acute Pain Management for Patients Receiving Maintenance Methadone or Buprenorphine Therapy". Annals of internal medicine 144 (2): 127–134. ISSN 0003-4819. PMC 1892816. PMID 16418412.

- ↑ Rosenquist, Richard W. (6 January 2016). Chronic Pain Management for the Hospitalized Patient. Oxford University Press. p. 300. ISBN 9780199349302.

- ↑ Thomas, Stephen H. (23 April 2013). "Management of Pain in the Emergency Department". ISRN Emergency Medicine 2013. doi:10.1155/2013/583132. Retrieved 7 February 2016.

Fentanyl, the most potent opioid that is routinely used in most ED and prehospital settings, is no new drug.

External links

- U.S. National Library of Medicine: Buprenorphine information portal

- U.S. Federal government buprenorphine program for opioid addiction

- U.S. Federal Government listing of doctors who can prescribe buprenorphine for opioid addiction

- NAABT: Non-profit buprenorphine advocate

- Australian national buprenorphine policy

- The bitter pill: A Wired Magazine article on Suboxone

- Subu Must Die – How a nation of junkies went cold turkey: A New Republic article on Subutex abuse in the nation of Georgia

- Erowid buprenorphine page

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||