Subspecies of Canis lupus

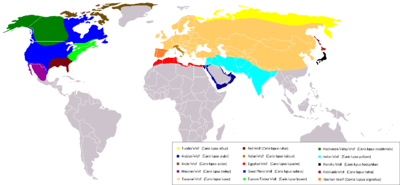

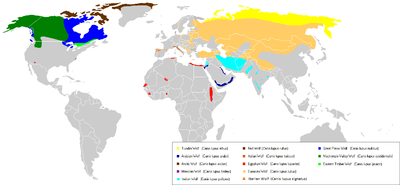

Canis lupus has 40 subspecies currently described, including the dingo, Canis lupus dingo, and the domestic dog, Canis lupus familiaris, and many subspecies of wolf throughout the Northern Hemisphere. The nominate subspecies is Canis lupus lupus.

Canis lupus is assessed as least concern by the IUCN, as its relatively widespread range and stable population trend mean that the species, at global level, does not meet, or nearly meet, any of the criteria for the threatened categories. However, some local populations are classified as endangered,[1] and some subspecies are endangered or extinct.

Biological taxonomy is not fixed, and placement of taxa is reviewed as a result of new research. The current categorization of subspecies of Canis lupus is shown below. Also included are synonyms, which are now discarded duplicate or incorrect namings, or in the case of the domestic dog synonyms, old taxa referring to subspecies of domestic dog which, when the dog was declared a subspecies itself, had nowhere else to go. Common names are given but may vary, as they have no set meaning.

Geographical variations

Wolves show a great deal of polymorphism geographically, though they can interbreed. The Zoological Gardens of London for example once successfully managed to mate a male European wolf to an Indian female, resulting in a pup bearing an almost exact likeness to its sire.[2]

Europe

European wolves tend to have fur with less soft wool intermixed than American wolves. Their heads are narrower, their ears longer, higher placed and somewhat closer to each other. Their loins are more slender, their legs longer, their feet narrower, and their tails more thinly clothed with fur.[3] Pelt color in European wolves ranges from white, cream, red, grey and black, sometimes with all colors combined. Wolves in central Europe tend to be more richly colored than those in Northern Europe. Eastern European wolves tend to be shorter and more heavily built than northern Russian ones.[4]

North America

North American wolves are generally the same size as European wolves, but have shorter legs, larger, rounder heads, broader, more obtuse muzzles, and a sensible depression at the union of nose and forehead, which is more arched and broad. Their ears are shorter and have a more conical form. They typically lack the black mark on the forelegs, as is the case in European races. They have long and comparatively fine fur, mixed with a shorter wooly hair, and are more robust.[3] Fur color in American wolves ranges from white, black, red, yellow, brown, grey, and grizzled skins, and others representing every shade between, although usually each locality has its prevailing tint. There are pronounced differences in North American wolves of different localities; wolves from Texas and New Mexico are comparatively slim animals with small teeth.[5] Mexican wolves in particular resemble some European wolves in stature, though their heads are usually broader, their necks thicker, their ears longer and their tails shorter.[6] Wolves of the central and northern chains of the Rocky Mountains and coastal ranges are more formidable animals than the more southern plains wolves, and resemble Russian and Scandinavian wolves in size and proportions.[5]

List of subspecies

Canis lupus subspecies

Subspecies as of 2005:[7]

| Subspecies | Authority | Description | Range | Synonyms | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eurasian wolf Canis lupus lupus (nominate subspecies)

|

Linnaeus 1758[8] | Generally a large subspecies measuring 105–160 cm in length and weighing 40–80 kg. The pelt is usually a mix of rusty ocherous and light grey.[9] | Has the largest range among wolf subspecies and is the most common in Europe and Asia, ranging through Western Europe, Scandinavia, Caucasus, Russia, China, Mongolia, and the Himalayan Mountains. Habitat overlaps with Indian wolf in some regions of Turkey. | altaicus (Noack, 1911), argunensis (Dybowski, 1922), canus (Sélys Longchamps, 1839), communis (Dwigubski, 1804), deitanus (Cabrera, 1907), desertorum (Bogdanov, 1882), flavus (Kerr, 1792), fulvus (Sélys Longchamps, 1839), italicus (Altobello, 1921), kurjak (Bolkay, 1925), lycaon (Trouessart, 1910), major (Ogérien, 1863), minor (Ogerien, 1863), niger (Hermann, 1804), orientalis (Wagner, 1841), orientalis (Dybowski, 1922), signatus (Cabrera, 1907)[10] | ||

| Tundra wolf Canis lupus albus

|

Kerr 1792[11] | A large subspecies, with adults measuring 112–137 cm, and weighing 36.6–52 kg. The fur is very long, dense, fluffy and soft and is usually very light and grey in color. The lower fur is lead-grey and the upper fur is reddish-grey.[9] | Northern tundra and forest zones in the European and Asian parts of Russia and Kamchatka. Outside Russia, its range includes the extreme north of Scandinavia[9] | dybowskii (Domaniewski, 1926), kamtschaticus (Dybowski, 1922),

turuchanensis (Ognev, 1923)[12] | ||

| † Kenai Peninsula wolf Canis lupus alces |

Goldman 1941[13] | A large wolf measuring over 200 cm in length and weighing 45–90 kg. It is thought that its large size was an adaptation to hunting the extremely large moose of the Kenai Peninsula.[14] | Kenai Peninsula | |||

| Arabian wolf Canis lupus arabs |

Pocock 1934[15] | A small, "desert adapted" wolf that is around 66 cm tall and weighs, on average, about 18 kg.[16] Its fur coat varies from short in the summer and long in the winter, possibly because of solar radiation.[17] | Southern Israel, Southern and western Iraq, Oman, Yemen, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, and probably some parts of the Sinai Peninsula | |||

| Arctic wolf Canis lupus arctos

|

Pocock 1935[18] | A medium-sized wolf that is between 64 and 79 cm tall and 89 to 189 cm long, weighing between 35 and 45 kg on average, though there have been specimens found weighing up to 68 kg.[19][20] | Canadian Arctic, Alaska and northern Greenland | |||

| Mexican wolf Canis lupus baileyi

|

Nelson and Goldman 1929[21] | A small subspecies which weighs 25–45 kg and measures 140–170 cm in total length (nose to tip of tail), and 72–80 cm in shoulder height. The pelt contains a mix of grey, black, brown, and rust colors in a characteristic pattern, with white underparts[22] | Northern Mexico, western Texas, southern New Mexico, and southeastern and central Arizona[22] | |||

| † Newfoundland wolf Canis lupus beothucus

|

G. M. Allen and Barbour 1937 | A white colored subspecies, extinct in 1911, typically measuring 180 cm in length and weighing 45 kg[14] | Newfoundland | |||

| † Bernard's wolf Canis lupus bernardi |

Anderson 1943 | This subspecies became extinct in 1934. It was described as "white with black-tipped hair along the ridge of the back".[23] | Limited to Banks and Victoria Islands in the arctic | banksianus (Anderson, 1943)[24] | ||

| Steppe wolf Canis lupus campestris

|

Dwigubski 1804 | A wolf of average size with short, coarse and sparse fur. The fur is light grey on the sides and rusty, brownish grey on the back[9] | Northern Ukraine, southern Kazakhstan, Caucasus and Trans-Caucasus[9] | bactrianus (Laptev, 1929), cubanenesis (Ognev, 1923), desertorum (Bogdanov, 1882)[25] | ||

| Tibetan wolf Canis lupus chanco

|

Gray 1863 | A small subspecies rarely exceeding 45 kg in weight. It is of a light, whitish-grey color, with an admixture of brownish tones on the upper part of the body[9] | Central Asia from Turkestan, Tien Shan throughout Tibet to Mongolia, Northern China, Shensi, Sichuan, Yunnan, the Western Himalayas in Kashmir from Chitral to Lahul.[26] Also occurs in the Korean peninsula[27] | coreanus (Abe, 1923), dorogostaiskii (Skalon, 1936), ekloni (Przewalski, 1883), filchneri (Matschie, 1907), karanorensis (Matschie, 1907), laniger (Hodgson, 1847), niger (Sclater, 1874), tschiliensis (Matschie, 1907)[28] | ||

| British Columbia wolf Canis lupus columbianus |

Goldman 1941 | Yukon, British Columbia, and Alberta | ||||

| Vancouver Island wolf Canis lupus crassodon |

Hall 1932 | A medium-sized subspecies, it is generally greyish-white or white in fur color. It is a very social subspecies and can usually be found roaming in packs of five to thirty-five individuals.[29] | Vancouver Island, British Columbia | |||

| Dingo Canis lupus dingo

|

Meyer 1793 | Generally 52–60 cm tall at the shoulders and measures 117 to 124 cm from nose to tail tip. The average weight is 13 to 20 kg.[30] Descended from Southeast Asia around 5,000 years ago by boat, the dingo is now largely wild.[31] Fur color is mostly sandy to reddish brown, but can include tan patterns and be occasionally black, light brown, or white[32] | Australia, Thailand, India, Indonesia, New Guinea and Solomon Islands | antarcticus (Kerr, 1792), australasiae (Desmarest, 1820), australiae (Gray, 1826), dingoides (Matschie, 1915), macdonnellensis (Matschie, 1915), novaehollandiae (Voigt, 1831), papuensis (Ramsay, 1879), tenggerana (Kohlbrugge, 1896), harappensis (Prashad, 1936), hallstromi (Troughton, 1957)[33] | ||

| Domestic dog Canis lupus familiaris

|

Linnaeus 1758 | Tends to have a 20% smaller skull and a 30% smaller brain,[34] as well as proportionately smaller teeth than other wolf subspecies.[35] The paws of a dog are half the size of those of a wolf, and their tails tend to curl upwards, another trait not found in wolves[16]

Through selective breeding by humans, the dog has developed into hundreds of varied breeds, and shows more behavioral and morphological variation than any other land mammal.[36] For example, height measured to the withers ranges from a 6 inches (150 mm) in the Chihuahua to 3.3 feet (1.0 m) in the Irish Wolfhound; color varies from white through grays (usually called "blue") to black, and browns from light (tan) to dark ("red" or "chocolate") in a wide variation of patterns; coats can be short or long, coarse-haired to wool-like, straight, curly, or smooth.[37] It is common for most breeds to shed this coat. |

Worldwide | aegyptius (Linnaeus, 1758), alco (C. E. H. Smith, 1839), americanus (Gmelin, 1792), anglicus (Gmelin, 1792), antarcticus (Gmelin, 1792), aprinus (Gmelin, 1792), aquaticus (Linnaeus, 1758), aquatilis (Gmelin, 1792), avicularis (Gmelin, 1792), borealis (C. E. H. Smith, 1839), brevipilis (Gmelin, 1792)

cursorius (Gmelin, 1792) domesticus (Linnaeus, 1758) extrarius (Gmelin, 1792), ferus (C. E. H. Smith, 1839), fricator (Gmelin, 1792), fricatrix (Linnaeus, 1758), fuillus (Gmelin, 1792), gallicus (Gmelin, 1792), glaucus (C. E. H. Smith, 1839), graius (Linnaeus, 1758), grajus (Gmelin, 1792), hagenbecki (Krumbiegel, 1950), haitensis (C. E. H. Smith, 1839), hibernicus (Gmelin, 1792), hirsutus (Gmelin, 1792), hybridus (Gmelin, 1792), islandicus (Gmelin, 1792), italicus (Gmelin, 1792), laniarius (Gmelin, 1792), leoninus (Gmelin, 1792), leporarius (C. E. H. Smith, 1839), major (Gmelin, 1792), mastinus (Linnaeus, 1758), melitacus (Gmelin, 1792), melitaeus (Linnaeus, 1758), minor (Gmelin, 1792), molossus (Gmelin, 1792), mustelinus (Linnaeus, 1758), obesus (Gmelin, 1792), orientalis (Gmelin, 1792), pacificus (C. E. H. Smith, 1839), plancus (Gmelin, 1792), pomeranus (Gmelin, 1792), sagaces (C. E. H. Smith, 1839), sanguinarius (C. E. H. Smith, 1839), sagax (Linnaeus, 1758), scoticus (Gmelin, 1792), sibiricus (Gmelin, 1792), suillus (C. E. H. Smith, 1839), terraenovae (C. E. H. Smith, 1839), terrarius (C. E. H. Smith, 1839), turcicus (Gmelin, 1792), urcani (C. E. H. Smith, 1839), variegatus (Gmelin, 1792), venaticus (Gmelin, 1792), vertegus (Gmelin, 1792)[38] | ||

| † Florida black wolf Canis lupus floridanus  |

Miller 1912 | A jet black wolf that is described as being extremely similar to the red wolf in both size and weight.[39] This subspecies became extinct in 1908.[40] | Florida | |||

| † Cascade mountain wolf Canis lupus fuscus |

Richardson 1839 | A cinnamon colored wolf measuring 165 cm and weighing 36–49 kg[14] | Cascade Range | |||

| † Gregory's wolf Canis lupus gregoryi |

Goldman 1937[41] | A medium-sized subspecies, though slender and tawny, its coat contains a mixture of various colors, including black, grey, white, and cinnamon.[41] | In and around the lower Mississippi River basin | gigas (Townsend, 1850)[42] | ||

| †Manitoba wolf Canis lupus griseoalbus |

Baird 1858 | North Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba | knightii (Anderson, 1945)[43] | |||

| †Hokkaidō wolf Canis lupus hattai

|

Kishida 1931 | Hokkaidō | rex (Pocock, 1935)[44] | |||

| †Honshū wolf Canis lupus hodophilax

|

Temminck 1839 | Honshū, Shikoku, and Kyūshū | hodopylax (Temminck, 1844), japonicus (Nehring, 1885)[45] | |||

| Hudson Bay wolf Canis lupus hudsonicus |

Goldman 1941 | Northern Manitoba and the Northwest Territories | ||||

| Northern Rocky Mountains wolf Canis lupus irremotus |

Goldman 1937[41][46] | This subspecies generally weighs 70–135 pounds (32–61 kg), making it one of the largest subspecies of the gray wolf in existence.[47] It is a lighter colored animal than its southern brethren, the Southern Rocky Mountains wolf, with a coat that includes far more white and less black. In general, the subspecies favors lighter colors, with black mixing in among them.[41][48] | Northern Rocky Mountains | |||

| Labrador wolf Canis lupus labradorius

|

Goldman 1937[41] | Labrador and northern Quebec; recent confirmed sightings on Newfoundland[49][50] | ||||

| Alexander Archipelago wolf Canis lupus ligoni |

Goldman 1937[41] | Alexander Archipelago | ||||

| Eastern (timber) wolf Canis lupus lycaon

|

Schreber 1775 | Mainly occupies the area in and around Algonquin Provincial Park in Ontario, and also ventures into adjacent parts of Quebec, Canada. It also may be present in Minnesota and Manitoba | canadensis (de Blainville, 1843), ungavensis (Comeau, 1940)[51] | |||

| Mackenzie River wolf Canis lupus mackenzii |

Anderson 1943 | Northwest Territories | ||||

| Baffin Island wolf Canis lupus manningi |

Anderson 1943 | Baffin Island | ||||

| † Mogollon mountain wolf Canis lupus mogollonensis |

Goldman 1937[41] | A dark colored wolf measuring 135–150 cm in length, and weighing 27–36 kg[14] | Arizona and New Mexico | |||

| †Texas (gray)wolf Canis lupus monstrabilis |

Goldman 1937[41] | Similar in size and color to C. lupus mogollonensis[14] | Texas and New Mexico | niger (Bartram, 1791)[52] | ||

| Great Plains wolf Canis lupus nubilus

|

Say 1823 | Minnesota, Michigan, and Wisconsin. Single wolves have been reported in the Dakotas and as far south as Nebraska | variabilis (Wied-Neuwied, 1841)[53] labradorius, irremotus, youngi (Goldman, 1937) | |||

| Northwestern wolf Canis lupus occidentalis

|

Richardson 1829 | Western Canada | sticte (Richardson, 1829), ater (Richardson, 1829),[54] alces (Goldman, 1941), ater (Richardson, 1829), mackenzii (Anderson, 1943 (1908), pambasileus (Elliot, 1905), sticte (Richardson, 1829), tundrarum (Miller, 1912) | |||

| Greenland wolf Canis lupus orion

|

Pocock 1935 | Greenland | ||||

| Indian wolf Canis lupus pallipes

|

Sykes 1831 | A small wolf with pelage shorter than that of northern wolves, and with little to no underfur.[55] Fur color ranges from greyish red to reddish white with black tips. The dark V shaped stripe over the shoulders is much more pronounced than in northern wolves. The underparts and legs are more or less white.[56] | India, Pakistan, Iran, Turkey, Saudi Arabia and southern Israel | |||

| Yukon wolf Canis lupus pambasileus

|

Elliot 1905 | Alaska and Yukon | ||||

| Red wolf formerly Canis lupus rufus now Canis rufus

|

Audubon and Bachman 1851 | Has a brownish or cinnamon pelt, with grey and black shading on the back and tail. Generally intermediate in size between other American wolf subspecies and coyotes. Like other wolves, it has almond-shaped eyes, a broad muzzle and a wide nosepad, though like the coyote, its ears are proportionately larger. It has a deeper profile, a longer and broader head than the coyote, and has a less prominent ruff than wolves[57] | Eastern North Carolina[58] | |||

| Alaskan tundra wolf Canis lupus tundrarum

|

Miller 1912 | Has heavier dentition than pambasileus | Alaska | |||

| †Southern Rocky Mountains wolf Canis lupus youngi |

Goldman 1937[41] | A medium-size wolf that weighed around 90 lbs on average.[59][60] It is considered to have been the "second largest wolf in the United States".[61] The coloring of the subspecies tended toward black, with lighter areas on the edges of its fur and white in various small patches.[41] | Southern Rocky Mountains | |||

| †Austro-hungarian wolf | M. Mojsisovics 1887 | Central Europe To west Balkans |

Disputed subspecies and species

Two subspecies not mentioned in the list above are the Italian wolf (Canis lupus italicus) and the Iberian wolf (Canis lupus signatus). The wolves of the Apennine (Italian) and Iberian peninsulas have morphologically distinct features from other Eurasian wolves and each are considered by their researchers to represent their own subspecies.[62][63][64] In 2004, the genetic distinction of the Italian wolf subspecies was supported by analysis which consistently assigned all the wolf genotypes of a sample in Italy to a single group. This population also showed a unique mitochondrial DNA control-region haplotype, the absence of private alleles and lower heterozygosity at microsatellite loci, as compared to other wolf populations.[65] In 2010, a genetic analysis indicated that the single Apeninne wolf haplotype, and one of the two Iberian haplotypes, belonged to the same haplogroup as the prehistoric wolves of Europe.[66] The taxonomic reference Mammal Species of the World (2005) does not recognize Canis lupus signatus nor Canis lupus italicus, however NCBI/Genbank does list Canis lupus signatus[67] and publishes research papers under that name Canis lupus italicus.[68]

In 2007, genetic research indicated that two haplotypes of the Indian wolf populations located in the Indian subcontinent may represent a distinct species. Similar results were obtained for the Himalayan wolf, which is traditionally placed under the Tibetan wolf (Canis lupus chanco).[69] A call for more fieldwork has been made.[70] The taxonomic reference Mammal Species of the World (2005) does not recognize Canis himalayensis nor Canis indica, however NCBI/Genbank does list Canis lupus himalayensis[71] and Canis lupus indica.[72]

The red wolf is listed above, despite being considered a distinct species by many other authorities, including the US Fish and Wildlife Service, the main government authority of red wolves.[73] Some studies have concluded that red wolves, along with eastern wolves, evolved in North America between 150,000 and 300,000 years ago independent from gray wolves in Eurasia.[74] The taxonomic reference Mammal Species of the World (2005) does not recognize Canis rufus, however NCBI/Genbank lists it.[75]

The eastern wolf is also considered a distinct species by the USFWS.[73] However, this classification is still controversial and a review stated that it was "not well-supported by best available science."[76] The taxonomic reference Mammal Species of the World (2005) does not recognize Canis lycaon, however NCBI/Genbank lists it.[77]

As of 2005, the African wolf is listed as a subspecies of the golden jackal by the third and current edition of Mammal Species of the World.[78] In the early 2010s research disputed this, as mtDNA of wolf-like canids in various locations in northern, western, and eastern Africa more closely resemble those of gray wolves than golden jackals.[79][80] In 2015, a series of analyses on the species' mitochondrial DNA and nuclear genome indicated that it was distinct from both the golden jackal and the grey wolf, and more closely related to grey wolves and coyotes. [81]

In 2009, the Tibetan wolf was found to be genetically distinct enough to propose a separate species.[82][83] In 2011, another genetic study found that the Tibetan wolf might be an archaic pedigree within the wolf subspecies, however the study defined Canis lupus laniger as the Tibetan wolf distinct from Canis lupus chanco the Mongolian wolf.[84] In 2013, a major genetic study of dogs and wolves included the DNA sequences of 2 Tibetan wolves but then "excluded two aberrant modern wolf sequences from this analysis since their phylogenetic positioning suggests only a distant relationship to all extant gray wolves and their taxonomic classification as a member of Canis lupus or a separate sub-species is a matter of debate."[85]:Sup The taxonomic reference Mammal Species of the World (2005) does not recognize Canis lupus laniger, however NCBI/Genbank lists it[86] as the Tibetan wolf, and separately Canis lupus chanco [87] as the Mongolian wolf.

See also

References

- ↑ Mech, L.D., Boitani, L. (2008). "Canis lupus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2011.1. International Union for Conservation of Nature. Retrieved 12 August 2011.

- ↑ The Living Age, published by Littell, Son and Co., 1851

- 1 2 Richardson, J., Swainson, W., Kirby, W. (1829) Fauna Boreali-americana, Or, The Zoology of the Northern Parts of British America: Containing Descriptions of the Objects of Natural History Collected on the Late Northern Land Expeditions, Under Command of Captain Sir John Franklin, R.N. J. Murray, London book preview

- ↑ Hutchinson's animals of all countries: the living animals of the world in picture and story. Volume I. 1923. p. 384.

- 1 2 Hunting the Grisly and Other Sketches by Theodore Roosevelt - Full Text Free Book (Part 3/3)

- ↑ The Natural History of Dogs: Canidæ Or Genus Canis of Authors. Including Also the Genera Hyæna and Proteles by Charles Hamilton Smith, contributor William Home Lizars, Samuel Highley, W. Curry, Junr. & Co, Published by W.H. Lizars, ... S. Highley, ... London; and W. Curry, jun. and Co. Dublin., 1839

- ↑ Wozencraft, W.C. (2005). "Order Carnivora". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ↑ "Canis lupus lupus Linnaeus, 1758". Integrated Taxonomic Information System.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Mammals of the Soviet Union Vol.II Part 1a, SIRENIA AND CARNIVORA (Sea cows; Wolves and Bears), V.G Heptner and N.P Naumov editors, Science Publishers, Inc. USA. 1998. ISBN 1-886106-81-9

- ↑ Wozencraft, W.C. (2005). "Order Carnivora". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ↑ "Canis lupus albus Kerr, 1792". Integrated Taxonomic Information System.

- ↑ Wozencraft, W.C. (2005). "Order Carnivora". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ↑ "Canis lupus alces Goldman, 1941". Integrated Taxonomic Information System.

- 1 2 3 4 5 The Encyclopedia of Vanished Species by David Day, Universe Books ltd. 1981. ISBN 0-947889-30-2

- ↑ "Canis lupus arabs Pocock, 1934". Integrated Taxonomic Information System.

- 1 2 Lopez, Barry (1978). Of wolves and men. New York: Scribner Classics. p. 320. ISBN 0-7432-4936-4.

- ↑ Fred H. Harrington, Paul C. Paquet (1982). Wolves of the World: Perspectives of Behavior, Ecology, and Conservation. p. 474. ISBN 0-8155-0905-7.

- ↑ "Canis lupus arctos Pocock, 1935". Integrated Taxonomic Information System.

- ↑ "White wolf of the North", World Wide Fund for Nature

- ↑ "Arctic wolf", Toronto Zoo

- ↑ "Canis lupus baileyi Nelson and Goldman, 1929". Integrated Taxonomic Information System.

- 1 2 "Green Fire" Returns to the Southwest: Reintroduction of the Mexican Wolf- Author(s): David R. Parsons. Source: Wildlife Society Bulletin, Vol. 26, No. 4, Commemorative Issue Celebrating the 50th Anniversary of "A Sand County Almanac" and the Legacy of Aldo Leopold (Winter, 1998), pp. 799–807. Published by: Allen Press

- ↑ "Bernard, P. and J.", The Eponym Dictionary of Mammals by Bo Beolens, Michael Watkins and Michael Grayson, JHU Press, 2009, Pg. 40

- ↑ Wozencraft, W.C. (2005). "Order Carnivora". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ↑ Wozencraft, W.C. (2005). "Order Carnivora". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ↑ Fauna of British India: Mammals Volume 2 by R. I. Pocock, printed by Taylor and Francis, 1941

- ↑ Walker, Brett L. (2005). The Lost Wolves Of Japan. p. 331. ISBN 0-295-98492-9.

- ↑ Wozencraft, W.C. (2005). "Order Carnivora". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ↑ "Preliminary Investigations of the Vancouver Island Wolf", Wolves of the world: perspectives of behavior, ecology, and conservation by Fred H. Harrington and Paul C. Paquet, William Andrew, 1982, Pg. 54

- ↑ Ben Allen (2008). "Home Range, Activity Patterns, and Habitat use of Urban Dingoes" (PDF). 14th Australasian Vertebrate Pest Conference. Invasive Animals CRC. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 April 2009. Retrieved 2009-04-29.

- ↑ "A detailed picture of the origin of the Australian dingo, obtained from the study of mitochondrial DNA". Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (US National Library of Medicine

National Institutes of Health

Search) 101 (33): 12387–12390. August 17, 2004. doi:10.1073/pnas.0401814101. PMC 514485. PMID 15299143. line feed character in

|publisher=at position 33 (help) - ↑ Fleming, Peter; Laurie Corbett; Robert Harden; Peter Thomson (2001). Managing the Impacts of Dingoes and Other Wild Dogs. Commonwealth of Australia: Bureau of Rural Sciences.

- ↑ Wozencraft, W.C. (2005). "Order Carnivora". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ↑ Serpell, James (1995). The Domestic Dog; its evolution, behaviour and interactions with people - citing R.Schneider (1991) unpublished BA thesis. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press. p. 35. ISBN 0-521-42537-9.

- ↑ Coppinger, Ray (2001). Dogs: a Startling New Understanding of Canine Origin, Behavior and Evolution. New York: Scribner. ISBN 0-684-85530-5.

- ↑ Spady TC, Ostrander EA (January 2008). "Canine Behavioral Genetics: Pointing Out the Phenotypes and Herding up the Genes". American Journal of Human Genetics 82 (1): 10–8. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2007.12.001. PMC 2253978. PMID 18179880.

- ↑ The Complete dog book: the photograph, history, and official standard of every breed admitted to AKC registration, and the selection, training, breeding, care, and feeding of pure-bred dogs. New York, N.Y: Howell Book House. 1992. ISBN 0-87605-464-5.

- ↑ Wozencraft, W.C. (2005). "Order Carnivora". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ↑ "The Wolf", Alsatian Shepalute's: A New Breed for a New Millennium by Lois Denny, AuthorHouse, 2004, Pg. 42

- ↑ Klinkenberg, Jeff, "For saving the Florida panther, it's desperation time", St. Petersburg Times, February 11, 1990

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 "The Wolves of North America", E. A. Goldman, Journal of Mammalogy, Vol. 18, No. 1 (Feb., 1937), pp. 37–45

- ↑ Wozencraft, W.C. (2005). "Order Carnivora". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ↑ Wozencraft, W.C. (2005). "Order Carnivora". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ↑ Wozencraft, W.C. (2005). "Order Carnivora". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ↑ Wozencraft, W.C. (2005). "Order Carnivora". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ↑ "Canis lupus irremotus Goldman, 1937". Integrated Taxonomic Information System.

- ↑ Nelson King (2007). "Wolves in Yellowstone: A Short History". Yellowstone Insider.

- ↑ B. J. Verts & Leslie N. Carraway (1998). "Canis lupus Linnaeus, 1758". Land Mammals of Oregon. University of California Press. pp. 360–363. ISBN 978-0-520-21199-5.

- ↑ "Wolf in Newfoundland probably made it to island on ice, experts say". The Telegram. 25 May 2012. Retrieved 26 August 2012.

- ↑ "Genetic Retesting of DNA Confirms Second Wolf on Island of Newfoundland". Department of Environment and Conservation, Newfoundland and Labrador. 23 August 2012. Retrieved 26 August 2012.

- ↑ Wozencraft, W.C. (2005). "Order Carnivora". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ↑ Wozencraft, W.C. (2005). "Order Carnivora". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ↑ Wozencraft, W.C. (2005). "Order Carnivora". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ↑ Wozencraft, W.C. (2005). "Order Carnivora". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ↑ NATURAL HISTORY OF THE MAMMALIA OF INDIA AND CEYLON by Robert A. Sterndale, THACKER, SPINK, AND CO. BOMBAY: THACKER AND CO., LIMITED. LONDON: W. THACKER AND CO. 1884.

- ↑ A monograph of the canidae by St. George Mivart, F.R.S, published by Alere Flammam. 1890

- ↑ "Red Wolf" (PDF). canids.org.

- ↑ Red Wolf Recovery Project from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Services

- ↑ "Letters to the Editor" - The Idaho Statesman

- ↑ "The Company of Wolves" - Google Books

- ↑ "The wolves of North America" - Google Books

- ↑ The wolf in Spain

- ↑ Canis lupus italicus

- ↑ J. Vos: Food habits and livestock depredation of two Iberian wolf packs (Canis lupus signatus) in the north of Portugal. Journal of Zoology (2000), 251: 457-462 Cambridge University Press. online abstract

- ↑ V. LUCCHINI, A. GALOV and E. RANDI Evidence of genetic distinction and long-term population decline in wolves (Canis lupus) in the Italian Apennines. Molecular Ecology (2004) 13, 523–536. abstract online

- ↑ Pilot, M. G.; Branicki, W.; Jędrzejewski, W. O.; Goszczyński, J.; Jędrzejewska, B. A.; Dykyy, I.; Shkvyrya, M.; Tsingarska, E. (2010). "Phylogeographic history of grey wolves in Europe". BMC Evolutionary Biology 10: 104. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-10-104. PMC 2873414. PMID 20409299.

- ↑ "Canis lupus signatus".

- ↑ "NCBI search Canis lupus italicus".

- ↑ R. K. Aggarwal, T. Kivisild, J. Ramadevi, L. Singh: Mitochondrial DNA coding region sequences support the phylogenetic distinction of two Indian wolf species. Journal of Zoological Systematics and Evolutionary Research, Volume 45 Issue 2 Page 163-172, May 2007 online

- ↑ Shrotriya, Lyngdoh, Habib (October 25, 2012). "Wolves in Trans-Himalayas: 165 years of taxonomic confusion" (PDF). Current Science, Vol. 103, No. 8. Retrieved June 27, 2014.

- ↑ "Canis lupus himalayensis".

- ↑ "Canis lupus indica".

- 1 2 Chambers, Steven M.; Fain, Steven R.; Fazio, Bud; Amaral, Michael (2012). "An account of the taxonomy of North American wolves from morphological and genetic analyses". North American Fauna 77: 1–67. doi:10.3996/nafa.77.0001.

- ↑ "DNA profiles of the eastern Canadian wolf and the red wolf provide evidence for a common evolutionary history independent of the gray wolf". Canadian Journal of Zoology 78 (12): 2156–2166. December 2000. doi:10.1139/z00-158.

- ↑ "Canis rufus".

- ↑ "Review of Proposed Rule Regarding Status of the Wolf Under the Endangered Species Act" (PDF). January 2014. Retrieved June 6, 2015.

- ↑ "Canis lycaon".

- ↑ Wozencraft, W.C. (2005). "Order Carnivora". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 532–628. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ↑ Gaubert P, Bloch C, Benyacoub S, Abdelhamid A, Pagani P, et al. (2012). "Reviving the African Wolf Canis lupus lupaster in North and West Africa: A Mitochondrial Lineage Ranging More than 6,000 km Wide". PLoS ONE 7 (8): e42740. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0042740. PMC 3416759. PMID 22900047.

- ↑ Gaubert P, Bloch C, Benyacoub S, Abdelhamid A, Pagani P; et al. (2012). "Reviving the African Wolf Canis lupus lupaster in North and West Africa: A Mitochondrial Lineage Ranging More than 6,000 km Wide". PLoS ONE 7 (8): e42740. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0042740. PMC 3416759. PMID 22900047.

- ↑ http://www.cell.com/current-biology/abstract/S0960-9822%2815%2900787-3

- ↑ Meng, Chao; Zhang, Honghai; Meng, Qingcheng (2009). "Mitochondrial genome of the Tibetan wolf". Mitochondrial DNA 20 (2–3): 61–3. doi:10.1080/19401730902852968. PMID 19347764.

- ↑ Zhao, C; Zhang, H; Zhang, J; Chen, L; Sha, W; Yang, X; Liu, G (2014). "The complete mitochondrial genome sequence of the Tibetan wolf (Canis lupus laniger)". Mitochondrial DNA 27: 1. doi:10.3109/19401736.2013.865181. PMID 24438245.

- ↑ Zhang, Honghai; Chen, Lei (2010). "The complete mitochondrial genome of dhole Cuon alpinus: Phylogenetic analysis and dating evolutionary divergence within canidae". Molecular Biology Reports 38 (3): 1651–60. doi:10.1007/s11033-010-0276-y. PMID 20859694.

- ↑ Thalmann, O. (2013). "Complete Mitochondrial Genomes of Ancient Canids Suggest a European Origin of Domestic Dogs". Science (AAAS) 342 (6160): 871–874. doi:10.1126/science.1243650. PMID 24233726.

- ↑ "Canis lupus laniger".

- ↑ "Canis lupus chanco".

External links

- Canis lupus on the ITIS (Integrated Taxonomic Information System)

- Citations for Mammal Species of the World, as a PDF

- Ancient origin and evolution of the Indian wolf including discussion on naming.

- Wolf subspecies list with photos and maps

- Animal Corner, UK list of wolves

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

.jpg)

_Greenland_draught_wolf.jpg)