Suebi

The Suevi, (or Suebi, Suavi (Jordanes, Procopius), Suevians etc.), were a large group of related Germanic peoples who lived in Germania and were first mentioned by Julius Caesar in connection with Ariovistus' campaign in Gaul, c. 58 BC.[1] While Caesar treated them as one Germanic tribe, though the largest and most warlike, later authors such as Tacitus, Pliny and Strabo specified that the Suevi "do not, like the Chatti or Tencteri, constitute a single nation. They actually occupy more than half of Germany, and are divided into a number of distinct tribes under distinct names, though all generally are called Suebi".[2] "At one time, classical ethnography had applied the name "Suevi" to so many Germanic tribes that it appeared as though in the first centuries A.D. this native name would replace the foreign name "Germans".[3]

Classical authors noted that the Suevic tribes, compared to other Germanic tribes, were very mobile, and not reliant upon agriculture.[4] Various Suevic groups moved from the direction of the Baltic sea and river Elbe, becoming a periodic threat to the Roman Empire on their Rhine and Danube frontiers. Toward the end of the empire, the Alamanni, also referred to as Suebi, first settled in the Agri Decumates and then crossed the Rhine and occupied Alsace. This region is now still called Swabia, an area in southwest Germany whose modern name derives from the Suebi. (In a broader sense, their eastern neighbours the Bavarians and Thuringians can be said to have Suebic ancestry.) Other Suebi entered Gaul and some moved as far as Gallaecia (modern Galicia, in Spain, and Northern Portugal) and established a Suebic Kingdom of Gallaecia there which lasted for 170 years until its integration into the Visigothic Kingdom.

Among various groups who settled under Frankish rule in Gaul, there may have been Suevi living in the Scheldt area in the 6th and 7th centuries, who are supposed to have given their name to the Dutch province of Zeeland.[5]

Etymology

Etymologists trace the name from Proto-Germanic, *swēbaz, either based on the Proto-Germanic root *swē- meaning "one's own" people, or on the third-person reflexive pronoun;[6] or from an earlier Indo-European root *swe-.[7] The etymological sources list the following ethnic names as also from the same root: Suiones, Semnones, Samnites, Sabelli, Sabini, indicating the possibility of a prior more extended and common Indo-European ethnic name, "our own people". Alternatively, it may be borrowed from a Celtic word for "vagabond".[8]

Classification

More than one tribe

Caesar placed the Suebi east of the Ubii apparently near modern Hesse, in the position where later writers mention the Chatti, and he distinguished them from their allies the Marcomanni. Some commentators believe that Caesar's Suebi were the later Chatti or possibly the Hermunduri, or even the Semnones.[9] Later authors use the term Suebi more broadly, "to cover a large number of tribes in central Germany".[10] Although no classical authors explicitly call the Chatti Suevic, Pliny the Elder (23 AD – 79 AD), reported in his Natural History that the Hermiones were a large grouping of related Germanic gentes or "tribes" including not only the Suebi, but also the Hermunduri, Chatti and Cherusci.[11] Whether or not the Chatti were ever considered Suevi, both Tacitus and Strabo distinguish the two partly because the Chatti were more settled in one territory, whereas Suevi remained less settled.[12]

The definitions of the greater ethnic groupings within Germania were apparently not always consistent and clear, especially in the case of mobile groups such as the Suevi. Whereas Tacitus reported three main kinds of German peoples, Hermiones, Istvaeones, and Ingvaeones, Pliny specifically adds two more genera or "kinds", the Bastarnae and the Vandili (Vandals). The Vandili were tribes east of the Elbe, including the well-known Silingi, Goths, and Burgundians, an area which Tacitus treated as Suebic. That the Vandals might be a separate type of Germanic people is a possibility Tacitus noted also, but for example the Varini are named as Vandilic by Pliny, and specifically Suebic by Tacitus.

Also the modern term "Elbe Germanic" covers a large grouping of Germanic peoples that at least overlaps with the classical terms "Suevi" and "Hermiones". However this term was developed mainly as an attempt to define the ancient peoples who must have spoken the Germanic dialects that led to modern Upper German dialects spoken in Austria, Bavaria, Thuringia, Alsace, Baden-Württemberg and German speaking Switzerland. This was proposed by Friedrich Maurer as one of five major Kulturkreise or "culture-groups" whose dialects developed in the southern German area from the first century BC through to the fourth century AD.[13] Apart from his own linguistic work with modern dialects, he also referred to the archaeological and literary analysis of Germanic tribes done earlier by Gustaf Kossinna[14] In terms of these proposed ancient dialects, the Vandals, Goths and Burgundians are generally referred to as members of an Eastern germanic group, distinct from the Elbe Germanic.

Tribes names in classical sources

Northern bank of the Danube

In the time of Caesar, southern Germany was Celtic, but coming under pressure from Germanic groups led by the Suebi. As described later by Tacitus, what is today southern Germany between the Danube, the Main river, and the Rhine had been deserted by the departure of two large Celtic nations, the Helvetii in modern Schwaben and the Boii further east near the Hercynian forest.[15] In addition, also near the Hercynian forest Caesar believed that the Celtic Tectosages had once lived. All of these peoples had for the most part moved by the time of Tacitus.

Strabo (64/63 BC – c. 24 AD), in Book IV (6.9) of his Geography also associates the Suebi with the Hercynian Forest and the south of Germania north of the Danube. He describes a chain of mountains north of the Danube that is like a lower extension of the Alps, possibly the Swabian Alps, and further east the Gabreta forest, possibly the modern Bohemian forest. In Book VII (1.3) Strabo specifically mentions as Suevic peoples the Marcomanni, who under King Marobodus had moved into the same Hercynian forest as the Coldui (possibly the Quadi), taking over an area called "Boihaemum". This king "took the rulership and acquired, in addition to the peoples aforementioned, the Lugii (a large tribe), the Zumi, the Butones, the Mugilones, the Sibini, and also the Semnones, a large tribe of the Suevi themselves". Some of these tribes were "inside the forest" and some "outside of it".[16] Tacitus confirms the name "Boiemum", saying it was a survival marking the old traditional population of the place, the Celtic Boii, though the population had changed.[15]

Tacitus describes a series of very powerful Suebian states in his own time, running along the north of the Danube which was the frontier with Rome, and stretching into the lands where the Elbe originates in the modern day Czech Republic. Going from west to east the first were the Hermunduri, living near the sources of the Elbe and stretching across the Danube into Roman Rhaetia.[17] Next came the Naristi, the Marcomanni, and then the Quadi. The Quadi are on the edge of greater Suebia, having the Sarmatians to the southeast.[18]

Claudius Ptolemy the geographer did not always state which tribes were Suebi, but along the northern bank of the Danube, from west to east and starting at the "desert" formerly occupied by the Helvetii, he names the Parmaecampi, then the Adrabaecampi, and then a "large people" known as the Baemoi (whose name appears to recall the Boii again), and then the Racatriae. North of the Baemoi, is the Luna forest which has iron mines, and which is south of the Quadi. North of the Adrabaecampi, are the Sudini and then the Marcomanni living in the Gambreta forest. North of them, but south of the Sudetes mountains (which are not likely to be the same as the modern ones of that name) are the Varisti, who are probably the same as Tacitus' "Naristi" mentioned above.

Jordanes writes that in the early 4th century the Vandals had moved to the north of the Danube, but with the Marcomanni still to their west, and the Hermunduri still to their north. A possible sign of confusion in this comment is that he equates the area in question to later Gepidia, which was further south, in Pannonia, modern Hungary, and east of the Danube.[19] In general, as discussed below, the Danubian Suebi, along with the neighbours such as the Vandals, apparently moved southwards into Roman territories, both south and east of the Danube, during this period.

Approaching the Rhine

Caesar describes the Suebi as pressing the German tribes of the Rhine, such as the Tencteri, Usipetes and Ubii, from the east, forcing them from their homes. While emphasizing their warlike nature he writes as if they had a settled homeland somewhere between the Cherusci and the Ubii, and separated from the Cherusci by a deep forest called the Silva Bacenis. He also describes the Marcomanni as a tribe distinct from the Suebi, and also active within the same alliance. But he does not describe where they were living.

Strabo wrote that the Suebi "excel all the others in power and numbers."[20] He describes Suebic peoples (Greek ethnē) as having come to dominate Germany between the Rhine and Elbe, with the exception of the Rhine valley, on the frontier with the Roman empire, and the "coastal" regions north of the Rhine.

The geographer, Ptolemy (c. AD 90 – c. AD 168), in a fairly extensive account of Greater Germany,[21] makes several unusual mentions of Suebi between the Rhine and the Elbe. He describes their position as stretching out in a band from the Elbe, all the way to the northern Rhine, near the Sugambri. The "Suevi Langobardi" are the Suevi located closest to the Rhine, far to the east of where most sources report them. To the east of the Langobardi, are the "Suevi Angili", extending as far north as the middle Elbe, also to the east of the position reported in other sources. It has been speculated that Ptolemy may have been confused by his sources, or else that this position of the Langobardi represented a particular moment in history.[22]

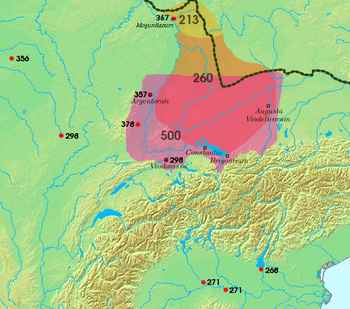

As discussed below, in the third century a large group of Suebi, also referred to as the Allemanni moved up to the Rhine bank in modern Schwaben, which had previously been controlled by the Romans. (They competed in this region with Burgundians who had arrived from further east.)

The Elbe

Strabo does not say much about the Suebi east of the Elbe, saying that this region was still unknown to Romans,[23] but mentions that a part of the Suebi live there, naming only specifically the Hermunduri and the Langobardi. But he mentions these are there because of recent defeats at Roman hands which had forced them over the river. (Tacitus, mentions that the Hermunduri were later welcomed on to the Roman border at the Danube.) In any case he says that the area near the Elbe itself is held by the Suebi.[24]

From Tacitus and Ptolemy we can derive more details:

- The Semnones, are described by Tacitus as "the oldest and noblest of the Suebi", and like the Suebi described by Caesar they have 100 cantons. Tacitus says that "the vastness of their community makes them regard themselves as the head of the Suevic race".[25] According to Ptolemy the "Suevi Semnones" live upon the Elbe and stretch as far east as a river apparently named after them, the Suevus, probably the Oder. South of them he places the Silingi, and then, again upon the Elbe, the Calucones. To the southeast further up the upper Elbe he places not the Hermunduri mentioned by other authors (who had possibly moved westwards and become Ptolemy's "Teuriochaemai", and the later Thuringii), but the Baenochaemae (whose name appears to be somehow related to the modern name Bohemia, and somehow derived from the older placename mentioned by Strabo and Tacitus as the capital of King Marobodus after he settled his Marcomanni in the Hercynian forest).

- The Langobardi live a bit further from Rome's borders, in "scanty numbers" but "surrounded by a host of most powerful tribes" and kept safe "by daring the perils of war" according to Tacitus.[26]

- Tacitus names seven tribes who live "next" after the Langobardi, "fenced in by rivers or forests" stretching "into the remoter regions of Germany". These all worshiped Nertha, or Mother Earth, whose sacred grove was on an island in the Ocean (presumably the Baltic Sea): Reudigni, Aviones, Anglii, Varini, Eudoses, Suarini and Nuitones.[26]

- At the mouth of the Elbe (and in the Danish peninsula), the classical authors do not place any Suevi, but rather the Chauci to the west of the Elbe, and the Saxons to the east, and in the "neck" of peninsula.

Note that while various errors and confusions are possible, Ptolemy places the Angles and Langobardi west of the Elbe, where they may indeed have been present at some points in time, given that the Suebi were often mobile.

East of the Elbe

It is already mentioned above that stretching between the Elbe and the Oder, the classical authors place the Suebic Semnones. Ptolemy places the Silingi to their south in the stretch between these rivers. These Silingi appear in later history as a branch of the Vandali, and were therefore likely to be speakers of East Germanic dialects. Their name is associated with medieval Silesia. Further south on the Elbe are the Baenochaemae and between them and the Askibourgian mountains Ptolemy names a tribe called the Batini (Βατεινοὶ), apparently north and/or east of the Elbe.

According to Tacitus, around the north of the Danubian Marcomanni and Quadi, "dwelling in forests and on mountain-tops", live the Marsigni, and Buri, who "in their language and manner of life, resemble the Suevi".[27] (Living partly subject to the Quadi are the Gotini and Osi, who Tacitus says speak respectively Gaulish and Pannonian, and are therefore not Germans.) Ptolemy also places the "Lugi Buri" in mountains, along with a tribe called the Corconti. These mountains, stretching from near the upper Elbe to the headwaters of the Vistula, he calls the Askibourgian mountains. Between these mountains and the Quadi he adds several tribes, from north to south these are the Sidones, Cotini (possibly Tacitus' Gotini) and the Visburgi. There is then the Orcynian (Hercyian) forest, which Ptolemy defines with relatively restricted boundaries, and then the Quadi.

Beyond this mountain range (probably the modern Sudetes) where the Marsigni and Buri lived, in the area of modern southwest Poland, Tacitus reported a multitude of tribes, the most widespread name of which was the Lugii. These included the Harii, Helveconae, Manimi, Helisii and Naharvali.[27] (Tacitus does not mention the language of the Lugii.) As mentioned above, Ptolemy categorizes the Buri amongst the Lugii, and concerning the Lugii north of the mountains, he named two large groups, the Lougoi Omanoi and the Lougoi Didounoi, who live between the "Suevus" river (probably the Oder river) and the Vistula, south of the Burgundi.

These Burgundians who according to Ptolemy lived between the Baltic sea Germans and the Lugii, stretching between the Suevus and Vistula rivers, were described by Pliny the Elder (as opposed to Tacitus) as being not Suevic but Vandili, amongst whom he also included the Goths, and the Varini, both being people living north of them near the Baltic coast. Pliny's "Vandili" are generally thought to be speakers of what modern linguists refer to as Eastern Germanic. Between the coastal Saxons and inland Suebi, Ptolemy names the Teutonari and the "Viruni" (presumably the Varini of Tacitus), and further east, between the coastal Farodini and the Suebi are the Teutones and then the Avarni. Further east again, between the Burgundians and the coastal Rugiclei were the "Aelvaeones" (presumably the Helveconae of Tacitus).

Baltic Sea

Tacitus called the Baltic sea the Suebian sea. (Pomponius Mela wrote in his Description of the World (III.3.31) beyond the Danish isles are "the farthest people of Germania, the Hermiones".)

North of the Lugii, near the Baltic Sea Tacitus places the Gothones (Goths), Rugii, and Lemovii. These three Germanic tribes share a tradition of having kings, and also similar arms - round shields and short swords.[27] Ptolemy says that east of the Saxons, from the "Chalusus" river to the "Suevian" river are the Farodini, then the Sidini up to the "Viadua" river, and after these the "Rugiclei" up to the Vistula river (probably the "Rugii" of Tacitus). He does not specify if these are Suevi.

In the sea, the states of the Suiones, "powerful in ships" are according to Tacitus Germans with the Suevic (Baltic) sea on one side and an "almost motionless" sea on the other more remote side. Modern commentators believe this refers to Scandinavia.[28] Closely bordering on the Suiones and closely resembling them, are the tribes of the Sitones.[29] Ptolemy describes Scandinavia as being inhabited by Chaedini in the west, Favonae and Firaesi in the east, Finni in the north, Gautae and Dauciones in the south, and Levoni in the middle. He does not describe them as Suebi.

Tacitus describes the non-Germanic Aestii on the eastern shore of the "Suevic Sea" (Baltic), "whose rites and fashions and style of dress are those of the Suevi, while their language is more like the British"[29] After giving this account, Tacitus says: "Here Suebia ends."[30] Therefore, for Tacitus geographic "Suebia" comprises the entire periphery of the Baltic Sea, including within it tribes not identified as Suebi or even Germanic. On the other hand, Tacitus does clearly consider there to be not only a Suebian region, but also Suebian languages, and Suebian customs, which all contribute to making a specific tribe more or less "Suebian".[31]

Cultural characteristics

Caesar noted that rather than grain crops, they spent time on husbandry and hunting. They wore animal skins, bathed in rivers, consumed milk and meat products, and prohibited wine, allowing trade only to dispose of their booty and otherwise they had no goods to export. They had no private ownership of land and were not permitted to stay resident in one place for more than one year. They were divided into 100 cantons, each of which had to provide and support 1000 armed men for the constant pursuit of war.

Strabo describes the Suebi and people from their part of the world as highly mobile and nomadic, unlike more settled and agricultural tribes such as the Chatti and Cherusci:

...they do not till the soil or even store up food, but live in small huts that are merely temporary structures; and they live for the most part off their flocks, as the Nomads do, so that, in imitation of the Nomads, they load their household belongings on their wagons and with their beasts turn whithersoever they think best.

Notable in classical sources, the Suebi can be identified by their hair style called the "Suebian knot", which "distinguishes the freeman from the slave";[32] or in other words served as a badge of social rank. The same passage points out that chiefs "use an even more elaborate style".

Tacitus mentions the sacrifice of humans practiced by the Semnones in a sacred grove[25] and the murder of slaves used in the rites of Nerthus practiced by the tribes of Schleswig-Holstein.[26] The chief priest of the Naharvali dresses as a woman and that tribe also worships in groves. The Harii fight at night dyed black. The Suiones own fleets of rowing vessels with prows at both ends.

Language

While there is debate possible about whether all tribes identified by Romans as Germanic spoke a Germanic language, the Suebi are generally agreed to have spoken one, and classical sources refer to a Suebian language. In particular, the Suebi are associated with the concept of an "Elbe Germanic" group of early dialects, entering Germany from the East, and originating on the Baltic. In late classical times, these dialects, by now situated to the south of the Elbe, and stretching across the Danube into the Roman empire, experienced the High German consonant shift that defines modern High German, and in its most extreme form, Upper Germanic dialects.[33]

Modern Swabian German, and Alemannic German more broadly, are therefore "assumed to have evolved at least in part" from Suebian.[34] However, Bavarian, Thuringian, the Langobardic language spoken by the Lombards of Italy, and standard "High German" itself, are also at least partly derived from the dialects spoken by the Suebi. (The only non-Suebian name among the major groups of Upper Germanic dialects is High Franconian, but this is on the transitional frontier with "Central" high German dialects, as is neighboring Thuringian.)[33]

Historical events

Ariovistus and the Suebi in 58 BC

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

Julius Caesar lived 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC. The Suebi he describes in his firsthand account, De Bello Gallico[35] were the "largest and the most warlike nation of all the Germans".

Caesar confronted a large army led by a Suevic King named Ariovistus in 58 BC who had been settled for some time in Gaul already, at the invitation of the Gaulish Arverni and Sequani as part of their war against the Aedui. He had already been recognized as a king by the Roman senate. Ariovistus forbade the Romans from entering into Gaul. Caesar on the other hand saw himself and Rome as an ally and defender of the Aedui.

The forces Caesar faced in battle were composed of "Harudes, Marcomanni, Tribocci, Vangiones, Nemetes, Sedusii, and Suevi". While Caesar was preparing for conflict, a new force of Suebi was led to the Rhine by two brothers, Nasuas and Cimberius, forcing Caesar to rush in order to try to avoid the joining of forces.

Caesar defeated Ariovistus in battle, forcing him to escape across the Rhine. When news of this spread, the fresh Suebian forces turned back in some panic, which led to local tribes living near the Rhine to take advantage of the situation, attacking them.

Caesar and the Suebi in 55 BC

Also reported within Caesar's accounts of the Gallic wars, the Suebi posed another threat in 55 BC.[36] The Germanic Ubii, who had worked out an alliance with Caesar, were complaining of being harassed by the Suebi, and the Tencteri and Usipetes, already forced from their homes, tried to cross the Rhine and enter Gaul by force. Caesar bridged the Rhine, the first known to do so, with a pile bridge, which though considered a marvel, was dismantled after only eighteen days. The Suebi abandoned their towns closest to the Romans, retreated to the forest and assembled an army. Caesar moved back across the bridge and broke it down, stating that he had achieved his objective of warning the Suebi. They in turn supposedly stopped harassing the Ubii. (The Ubii were later resettled on the east bank of the Rhine, in Roman territory.)

Rhine crossing of 29 BC

Cassius Dio, wrote the history of Rome for a Greek audience, and lived approximately AD 150 – 235. He reported that shortly before 29 BC the Suebi crossed the Rhine, only to be defeated by Gaius Carrinas who along with the young Octavian Caesar celebrated a triumph in 29 BC.[37] Shortly after they turn up fighting a group of Dacians in a gladiatorial display at Rome celebrating the consecration of the Julian hero-shrine.

The victory of Drusus in 9 BC

Suetonius (c. 69 AD – after 122 AD), gives the Suebi brief mention in connection with their defeat against Nero Claudius Drusus in 9 BC. He says that the Suebi and Sugambri "submitted to him and were taken into Gaul and settled in lands near the Rhine" while the other Germani were pushed "to the farther side of the river Albis" (Elbe).[38] He must have meant the temporary military success of Drusus, as it is unlikely the Rhine was cleared of Germans. Elsewhere he identifies the settlers as 40,000 prisoners of war, only a fraction of the yearly draft of militia.[39]

Florus (c. 74 AD – c. 130 AD), gives a more detailed view of the operations of 9 BC. He reports that the Cherusci, Suebi and Sicambri formed an alliance by crucifying twenty Roman centurions, but that Drusus defeated them, confiscated their plunder and sold them into slavery.[40] Presumably only the war party was sold, as the Suebi continue to appear in the ancient sources.

Florus's report of the peace brought to Germany by Drusus is glowing but premature. He built "more than five hundred forts" and two bridges guarded by fleets. "He opened a way through the Hercynian Forest", which implies but still does not overtly state that he had subdued the Suebi. "In a word, there was such peace in Germany that the inhabitants seemed changed ... and the very climate milder and softer than it used to be."

In the Annales of Tacitus, it is mentioned that after the defeat of 9 BC Augustus divided the Germans by making a separate peace with the Sugambri and Suebi under their king Maroboduus. This is the first mention of any permanent king of the Suebi.[41] However, Maroboduus' people was in most sources referred to as the king of the Marcomanni, a name that had already existed since Caesar's time, and which Caesar had treated as a separate people. At some point in this period the Marcomanni had come to be settled in the forested regions once inhabited by the Boii, in and around Bohemia.

Augustus planned in 6 AD to destroy the kingdom of Maroboduus, which he considered to be too dangerous for the Romans. The later Emperor Tiberius commanded twelve legions to attack the Marcomanni. But the outbreak of a revolt in Illyria, and the need for troops there, forced Tiberius to conclude a treaty with Maroboduus and to recognize him as king.[42]

Roman defeat in 9 AD

After the death of Drusus, the Cherusci annihilated three legions at the Battle of Teutoburg Forest and thereafter "... the empire ... was checked on the banks of the Rhine." While elements of the Suevi may have been involved, this was an alliance mainly made up of non-Suebic tribes from northwestern Germany, the Cherusci, Marsi, Chatti, Bructeri, Chauci, and Sicambri. The kingdom of the Marcomanni and their allies stayed out of the conflict and when Maroboduus was sent the head of the defeated Roman leader Varus, he sent it on to Rome for burial. Within his own alliance were various Suebic peoples, Hermunduri, Quadi, Semnones, Lugii, Zumi, Butones, Mugilones, Sibini and Langobards.

Aftermath of 9 AD

Subsequently Augustus placed Germanicus, the son of Drusus, in charge of the forces of the Rhine and he after dealing with a mutiny of the troops proceeded against the Cherusci and their allies, breaking their power finally at the battle of Idistavisus, a plain on the Weser. All eight legions and supporting units of Gauls were required to do that.[43] Germanicus' zeal led finally to his being replaced (17 AD) by his cousin Drusus, Tiberius' son, as Tiberius thought it best to follow his predecessor's policy of limiting the empire. Germanicus certainly would have involved the Suebi, with unpredictable results.[41]

Arminius, leader of the Cherusci and allies, now had a free hand. He accused Maroboduus of hiding in the Hercynian Forest while the other Germans fought for freedom, and accused Maroboduus of being the only king among the Germans. The two groups "turned their arms against each other." The Suebic Semnones and Langobardi rebelled against their king and went over to the Cherusci. Left with only the Marcomanni and Herminius' uncle, who had defected, Maroboduus appealed to Drusus, now governor of Illyricum, and was given only a pretext of aid.[44]

The resulting battle was indecisive but Maroboduus withdrew to Bohemia and sent for assistance to Tiberius. He was refused on the grounds that he had not moved to help Varus. Drusus encouraged the Germans to finish him off. A force of Goths under Catualda, a Marcomannian exile, bought off the nobles and seized the palace. Maroboduus escaped to Noricum and the Romans offered him refuge in Ravenna where he remained the rest of his life.[45] He died in 37 AD. After his expulsion the leadership of the Marcomanni was contested by their Suebic neighbours and allies, the Hermunduri and Quadi.

Marcomannic wars

In the 2nd century AD, the Marcomanni entered into a confederation with other peoples including the Quadi, Vandals, and Sarmatians, against the Roman Empire. The war began in 166, when the Marcomanni overwhelmed the defences between Vindobona and Carnuntum, penetrated along the border between the provinces of Pannonia and Noricum, laid waste to Flavia Solva, and could be stopped only shortly before reaching Aquileia on the Adriatic sea. The war lasted until Marcus Aurelius' death in 180.

In the third century Jordanes claims that the Marcomanni paid tribute to the Goths, and that the princes of the Quadi were enslaved. The Vandals, who had moved south towards Pannonia, were apparently still sometimes able to defend themselves.[46]

Migration period

In 259/60, a group of Suebi appear to have been the main element in the formation of a new tribal alliance known as the Alemanni who came to occupy the Roman frontier region known as the Agri Decumates, east of the Rhine and south of the Main. The Alemanni were sometimes simply referred to as Suebi by contemporaries, and the region came to be known as Swabia - a name which survives to this day. People in this region of Germany are still called Schwaben, a name derived from the Suebi.

These Suebi for the most part stayed on the right bank of the Rhine until 31 December 406, when much of the tribe joined the Vandals and Alans in breaching the Roman frontier by crossing the Rhine, perhaps at Mainz, thus launching an invasion of northern Gaul.

Other Suebi apparently remained in or near to the original homeland areas near the Elbe and the modern Czech Republic, occasionally still being referred to by this term. They expanded eventually into Roman areas such as Switzerland, Austria, and Bavaria, possibly pushed by groups arriving from the east.

Another group of Suebi, the so-called "northern Suebi" were mentioned in 569 under Frankish king Sigebert I in areas of today's Saxony-Anhalt which were known as Schwabengau or Svebengau at least until the 12th century. In connection to the Svebi, Saxons and Lombards, returning from the Italian Peninsula in 573, are also mentioned.

Further south, a group of Suebi settled in parts of Pannonia, after the Huns were defeated in 454 in the Battle of Nedao. Later, the Suebian king Hunimund fought against the Ostrogoths in the battle of Bolia in 469. The Suebian coalition lost the battle, and parts of the Suebi therefore migrated to southern Germany.[47]

Suevian Kingdom of Gallaecia

Migration

Suebi under their king Hermeric, probably coming from the Alemanni, or maybe from the Quadi (or both), worked their way into the south of France, eventually crossing the Pyrenees and entering the Iberian Peninsula which was out of Imperial rule since the rebellion of Gerontius and Maximus in 409.

Passing through the Basque country, they settled in the Roman province of Gallaecia, in north-western Hispania (modern Galicia, Asturias, and northern Portugal), swore fealty to the Emperor Honorius and were accepted as foederati and permitted to settle, under their own autonomous governance. Contemporaneously with the self-governing province of Britannia, the kingdom of the Suebi in Gallaecia became the first of the sub-Roman kingdoms to be formed in the disintegrating territory of the Western Roman Empire. Suebic Gallaecia was the first kingdom separated from the Roman Empire to mint coins.

The Suebic kingdom in Gallaecia and northern Lusitania was established at 410 and lasted until 584. Smaller than the Ostrogothic kingdom of Italy or the Visigothic kingdom in Hispania, it reached a relative stability and prosperity—and even expanded military southwards—despite the occasional quarrels with the neighbouring Visigothic kingdom.

Settlement

The Germanic invaders and immigrants settled mainly in rural areas, as Idacius clearly stated: "The Hispanic, spred over cities and oppida..." and the "Barbarians, govern over the provinces". According to Dan Stanislawski, the Portuguese way of living in Northern regions is mostly inherited from the Suebi, in which small farms prevail, distinct from the large properties of Southern Portugal. Bracara Augusta, the modern city of Braga and former capital of Roman Gallaecia, became the capital of the Suebi. Orosius, at that time resident in Hispania, shows a rather pacific initial settlement, the newcomers working their lands[48] or serving as bodyguards of the locals.[49] Another Germanic group that accompanied the Suebi and settled in Gallaecia were the Buri. They settled in the region between the rivers Cávado and Homem, in the area known as Terras de Bouro (Lands of the Buri).[50]

As the Suebi quickly adopted the local language, few traces were left of their Germanic tongue, but for some words and for their personal and land names, adopted by most of the Galicians.[51] In Galicia four parishes and six villages are named Suevos or Suegos, i.e. Sueves, after old Suebic settlements.

Establishment

The Visigoths were sent in 416 by the Emperor to fight the Germanic invaders in Hispania, but they soon re-established themselves as foederati in Aquitania after completely defeating the Alans and the Silingi Vandals. The absence of competition permitted, first the Asdingi Vandals and later the Suebi, to expand South and East. At its heyday Suebic Gallaecia extended as far south as Mérida and Seville, capitals of the Roman provinces of Lusitania and Betica, while their expeditions reached Zaragoza and Lleida.

In 438 Hermeric ratified the peace with the Gallaeci, the local and just partially romanized rural population, and sick and weary of fighting abdicated in favour of his son Rechila, who proved to be a notable general, defeating first Andevotus, Romanae militiae dux,[52] and later Vitus magister utriusque militiae. In 448, Rechila died, leaving the crown to his son Rechiar who had converted to Roman Catholicism circa 447. Soon, he married a daughter of the Gothic king Theodoric I, and began a wave of attacks on the Tarraconense, still a Roman province. By 456 the campaigns of Rechiar clashed with the interests of the Visigoths, and a large army of Roman federates (Visigoths under the command of Theodoric II, Burgundians directed by kings Gundioc and Chilperic) crossed the Pyrenees into Hispania, and defeated the Suebi near modern-day Astorga. Rechiar was executed after being captured by his brother-in-law, the Visigothic king Theodoric II. In 459, Roman Emperor Majorian defeated the Suebi, briefly restoring Roman rule in northern Hispania. Nevertheless, the Suebi became free of Roman control forever after Majorian was assassinated two years later. The Suebic kingdom then became cornered in the northwest, in Gallaecia and northern Lusitania, where political division and civil war arose among several pretenders to the royal throne. After years of turmoil, Remismund was recognized as the sole king of the Suebi, bringing forth a politic of friendship with the Visigoths, and favoring the conversion of his people to Arianism.

Last years of the kingdom

In 561 king Ariamir called the catholic First Council of Braga, which dealt with the old problem of the Priscillianism heresy. Eight years after, in 569, king Theodemir called the First Council of Lugo,[53] in order to increase the number of dioceses within his kingdom. Its acts have been preserved through a medieval resume known as Parrochiale Suevorum or Divisio Theodemiri.

Defeat by the Visigoths

In 570 the Arian king of the Visigoths, Leovigild, made his first attack on the Suebi. Between 572 and 574, Leovigild invaded the valley of the Douro, pushing the Suebi west and northwards. In 575 the Suebic king, Miro, made a peace treaty with Leovigild in what seemed to be the beginning of a new period of stability. Yet, in 583 Miro supported the rebellion of the Catholic Gothic prince Hermenegild, engaging in military action against king Leovigild, although Miro was defeated in Seville when trying to break on through the blockade on the Catholic prince. As a result, he was forced to recognize Leovigild as friend and protector, for him and for his successors, dying back home just some months later. His son, king Eboric, confirmed the friendship with Leovigild, but he was deposed just a year later by his brother-in-law Audeca, giving Leovigild an excuse to attack the kingdom. In 585 AD, first Audeca and later Malaric, were defeated and the Suebic kingdom was incorporated into the Visigothic one as its sixth province. The Suebi were respected in their properties and freedom, and continued to dwell in Gallaecia, finally merging with the rest of the local population during the early Middle Ages.

Religion

Conversion to Arianism

The Suebi remained mostly pagan, and their subjects Priscillianist until an Arian missionary named Ajax, sent by the Visigothic king Theodoric II at the request of the Suebic unifier Remismund, in 466 converted them and established a lasting Arian church which dominated the people until the conversion to Chalcedonianism in the 560s.

Conversion to Chalcedonianism

Mutually incompatible accounts of the conversion of the Suebi to Chalcedonian Christianity are presented in the primary records:

- The minutes of the First Council of Braga — which met on 1 May 561 — state explicitly that the synod was held at the orders of a king named Ariamir. Of the eight assistant bishops, just one bears a Suebic name: Hildemir. While the Catholicism of Ariamir is not in doubt, that he was the first Chalcedonian monarch of the Suebi since Rechiar has been contested on the grounds that his Catholicism is not explicitly stated.[54] He was, however, the first Suebic monarch to hold a Catholic synod, and when the Second Council of Braga was held at the request of king Miro, a Catholic himself,[55] in 572, of the twelve assistant bishops five bears Suebic names: Remisol of Viseu, Adoric of Idanha, Wittimer of Ourense, Nitigis of Lugo and Anila of Tui.

- The Historia Suevorum of Isidore of Seville states that a king named Theodemar brought about the conversion of his people from Arianism with the help of the missionary Martin of Dumio.[56]

- According to the Frankish historian Gregory of Tours on the other hand, an otherwise unknown sovereign named Chararic, having heard of Martin of Tours, promised to accept the beliefs of the saint if only his son would be cured of leprosy. Through the relics and intercession of Saint Martin the son was healed; Chararic and the entire royal household converted to the Nicene faith.[57]

- By 589, when the Third Council of Toledo was held, and the Visigoth Kingdom of Toledo converses officially from Arianism to Catholicism, king Reccared I stated in its minutes that also "an infinite number of Suebi have converted", together with the Goths, which implies that the earlier conversion were either superficial or partial. In the same council 4 bishops from Gallaecia abjured of their Arianism. And so, the Suebic conversion is ascribed, not to a Suebe, but to a Visigoth by John of Biclarum, who puts their conversion alongside that of the Goths, occurring under Reccared I in 587–589.

Most scholars have attempted to meld these stories. It has been alleged that Chararic and Theodemir must have been successors of Ariamir, since Ariamir was the first Suebic monarch to lift the ban on Catholic synods; Isidore therefore gets the chronology wrong.[58][59] Reinhart suggested that Chararic was converted first through the relics of Saint Martin and that Theodemir was converted later through the preaching of Martin of Dumio.[54] Dahn equated Chararic with Theodemir, even saying that the latter was the name he took upon baptism.[54] It has also been suggested that Theodemir and Ariamir were the same person and the son of Chararic.[54] In the opinion of some historians, Chararic is nothing more than an error on the part of Gregory of Tours and never existed.[60] If, as Gregory relates, Martin of Dumio died about the year 580 and had been bishop for about thirty years, then the conversion of Chararic must have occurred around 550 at the latest.[57] Finally, Ferreiro believes the conversion of the Suebi was progressive and stepwise and that Chararic's public conversion was only followed by the lifting of a ban on Catholic synods in the reign of his successor, which would have been Ariamir; Thoedemir was responsible for beginning a persecution of the Arians in his kingdom to root out their heresy.[61]

Norse mythology

The name of the Suebi also appears in Norse mythology and in early Scandinavian sources. The earliest attestation is the Proto-Norse name Swabaharjaz ("Suebian warrior") on the Rö runestone and in the place name Svogerslev.[6] Sváfa, whose name means "Suebian",[62] was a Valkyrie who appears in the eddic poem Helgakviða Hjörvarðssonar. The kingdom Sváfaland also appears in this poem and in the Þiðrekssaga.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Suebi. |

Notes

- ↑ Menzel, Wolfgang; Mrs. George Horrocks (Translator); Edgar Saltus (Supplementary Chapter) (MDCCCXCIX). Germany from the Earliest Period: Volume I. New York: Peter Fenelon Collier. p. 89. Cite uses deprecated parameter

|coauthors=(help); Check date values in:|date=(help) - ↑ Tacitus Germania Section 8, translation by H. Mattingly.

- ↑ "Germanic Tribes". Late Antiquity. Harvard University Press. 1999. p. 467. ISBN 9780674511736

- ↑ "Caes. Gal. 4.1". Perseus.tufts.edu. Retrieved 2014-05-01.

- ↑ Gysseling, Maurits (1960). Toponymisch woordenboek van België, Nederland, Luxemburg, Noord-Frankrijk en West-Duitsland (vóór 1226) 2. Brussels. p. 1099. online. Gysseling suggested that the name Suebi contaminated the older name *sawjas 'sea-dwellers' with the root *saiwi- 'sea-'

- 1 2 Peterson, Lena. "Swābaharjaz" (PDF). Lexikon över urnordiska personnamn. Institutet för språk och folkminnen, Sweden. p. 16. Retrieved 2007-10-11. (Text in Swedish); for an alternative meaning, as "free, independent" see Room, Adrian (2006). "Placenames of the World: Origins and Meanings of the Names for 6,600 Countries, Cities, Territories, Natural Features and Historic Sites: Second Edition". Jefferson, North Carolina, and London: McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers: 363, 364. ISBN 0786422483.

|contribution=ignored (help); compare Suiones - ↑ Pokorny, Julius. "Root/Lemma se-". Indogermanisches Etymologisches Wörterbuch. Indo-European Etymological Dictionary (IEED), Department of Comparative Indo-European Linguistics, Leiden University. pp. 882–884. (German language text); locate by searching the page number.Köbler, Gerhard (2000). "*se-" (PDF). Indogermanisches Wörterbuch: 3. Auflage. p. 188. (German language text); the etymology in English is in Watkins, Calvert (2000). "s(w)e-". Appendix I: Indo-European Roots. The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language: Fourth Edition. Some related English words are sibling, sister, swain, self.

- ↑ Schrijver, Peter (2003). "The etymology of Welsh chwith and the semantics and morphology of PIE *k(w)sweibh-". In Russell, Paul. Yr Hen Iaith: Studies in Early Welsh. Aberystwyth: Celtic Studies Publications. ISBN 978-1-891271-10-6.

- ↑ Peck. "Harpers Dictionary of Classical Antiquities year=1898"

- ↑ Chambers, R. W. (1912). Widseth: a Study in Old English Heroic Legend. Cambridge: University Press. pp. 194, note on line 22 of Widsith. Republished in 2006 by Kissinger Publishing as ISBN 1-4254-9551-6.

- ↑ "Book IV section XIV". Perseus.tufts.edu. Retrieved 2014-05-01.

- ↑ "Strab. 7.1". Perseus.tufts.edu. Retrieved 2014-05-01.

- ↑ Maurer, Friedrich (1952) [1942]. Nordgermanen und Alemannen: Studien zur germanischen und frühdeutschen Sprachgeschichte, Stammes - und Volkskunde. Bern, München: A. Franke Verlag, Leo Lehnen Verlag.

- ↑ Kossinna, Gustaf (1911). Die Herkunft der Germanen. Leipzig: Kabitsch.

- 1 2 "Tac. Ger. 28". Perseus.tufts.edu. Retrieved 2014-05-01.

- ↑ "Strab. 7.1". Perseus.tufts.edu. Retrieved 2014-05-01.

- ↑ "Section 41". Perseus.tufts.edu. Retrieved 2014-05-01.

- ↑ "Section 42". Perseus.tufts.edu. Retrieved 2014-05-01.

- ↑ "Chapt 22". Romansonline.com. Retrieved 2014-05-01.

- ↑ Strabo (approximately 20 AD). Geographica. Book IV Chapter 3 Section 4. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ "''Geography'', Book II, chapter X". Penelope.uchicago.edu. Retrieved 2014-05-01.

- ↑ Schütte, Ptolemy's Maps of Northern Europe

- ↑ "''Geography'' 7.2". Perseus.tufts.edu. Retrieved 2014-05-01.

- ↑ "''Geography'' 7.3". Perseus.tufts.edu. Retrieved 2014-05-01.

- 1 2 Germania Section 39.

- 1 2 3 Germania Section 40.

- 1 2 3 "Section 43". Perseus.tufts.edu. Retrieved 2014-05-01.

- ↑ Section 44.

- 1 2 Germania Section 45

- ↑ Section 46.

- ↑ Tacitus' modern editor Arthur J. Pomeroy concludes "it is clear that there is no monolithic 'Suebic' group, but a series of tribes who may share some customs (for instance, warrior burials) but also vary considerably." Pomeroy, Arthur J. (1994). "Tacitus' Germania". The Classical Review: New Series 44 (1): 58–59. doi:10.1017/S0009840X00290446. A review in English of Neumann, Gunter; Henning Seemann. Beitrage zum Verstandnis der Germania des Tacitus, Teil II: Bericht uber die Kolloquien der Kommission fur die Altertumskunde Nord- und Mitteleuropas im Jahre 1986 und 1987. A German-language text.

- ↑ Section 38.

- 1 2 Robinson, Orrin (1992), Old English and its Closest Relatives pages 194-5.

- ↑ Waldman & Mason, 2006, Encyclopedia of European Peoples, p. 784.

- ↑ Book IV, sections 1-3, and 19; Book VI, section 10.

- ↑ Book IV sections 4-19.

- ↑ Dio, Lucius Claudius Cassius; Herbert Baldwin Foster (Translator). "Dio's Rome" (ascii text). Project Gutenberg. pp. Book 51 sections 21, 22. Cite uses deprecated parameter

|coauthors=(help) - ↑ Tranquillus, Gaius Suetonius. "The Life of Augustus". The Lives of the Twelve Caesars. Bill Thayer in LacusCurtius. pp. section 21.

- ↑ Tranquillus, Gaius Suetonius. "The Life of Tiberius". The Lives of the Twelve Caesars. Bill Thayer in LacusCurtius. pp. section 9.

- ↑ Florus, Lucius Annaeus. Epitome of Roman History. Book II section 30.

- 1 2 Book II section 26.

- ↑ Velleius Paterculus, Compendium of Roman History 2, 109, 5; Cassius Dio, Roman History 55, 28, 6-7

- ↑ Book II section 16.

- ↑ Book II sections 44-46.

- ↑ Book II sections 62-63.

- ↑ "chapt 16". Romansonline.com. Retrieved 2014-05-01.

- ↑ Geschichte der Goten. Entwurf einer historischen Ethnographie, C.H. Beck, 1. Aufl. (München 1979), 2. Aufl. (1980), unter dem Titel: Die Goten. Von den Anfängen bis zur Mitte des sechsten Jahrhunderts. 4. Aufl. (2001)

- ↑ "the barbarians, detesting their swords, turn them into ploughs", Historiarum Adversum Paganos, VII, 41, 6.

- ↑ "anyone wanting to leave or to depart, uses these barbarians as mercenaries, servers or defenders", Historiarum Adversum Paganos, VII, 41, 4.

- ↑ Domingos Maria da Silva, Os Búrios, Terras de Bouro, Câmara Municipal de Terras de Bouro, 2006. (in Portuguese)

- ↑ Medieval Galician records show more than 1500 different Germanic names in use for over 70% of the local population. Also, in Galicia and northern Portugal, there are more than 5.000 toponyms (villages and towns) based on personal Germanic names (Mondariz < *villa *Mundarici; Baltar < *villa *Baldarii; Gomesende < *villa *Gumesenþi; Gondomar < *villa *Gunþumari...); and several toponyms not based on personal names, mainly in Galicia (Malburgo, Samos < Samanos "Congregated", near a hundred Saa/Sá < *Sala "house, palace"...); and some lexical influence on the Galician language and Portuguese language, such as:

laverca "lark" < protogermanic *laiwarikō "lark"

brasa "torch; ember" < protogermanic *blasōn "torch"

britar "to break" < protogermanic *breutan "to break"

lobio "vine gallery" < protogermanic *laubjōn "leaves"

ouva "elf" < protogermanic *albaz "elf"

trigar "to urge" < protogermanic *þreunhan "to urge"

maga "guts (of fish)" < protogermanic *magōn "stomach" - ↑ Isidorus Hispalensis, Historia de regibus Gothorum, Vandalorum et Suevorum, 85

- ↑ Ferreiro, 199 n11.

- 1 2 3 4 Thompson, 86.

- ↑ St. Martin on Braga wrote in his Formula Vitae Honestae Gloriosissimo ac tranquillissimo et insigni catholicae fidei praedito pietate Mironi regi

- ↑ Ferreiro, 198 n8.

- 1 2 Thompson, 83.

- ↑ Thompson, 87.

- ↑ Ferreiro, 199.

- ↑ Thompson, 88.

- ↑ Ferreiro, 207.

- ↑ Peterson, Lena. (2002). Nordiskt runnamnslexikon, at Institutet för språk och folkminnen, Sweden. Archived October 14, 2013 at the Wayback Machine

Bibliography

- Ferreiro, Alberto. "Braga and Tours: Some Observations on Gregory's De virtutibus sancti Martini." Journal of Early Christian Studies. 3 (1995), p. 195–210.

- Thompson, E. A.. "The Conversion of the Spanish Suevi to Catholicism." Visigothic Spain: New Approaches. ed. Edward James. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1980. ISBN 0-19-822543-1.

- Reynolds, Robert L., 'Reconsideration of the history of the Suevi', Revue belge de pholologie et d'histoire, 35 (1957), p. 19–45.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Suebi. |

- The Chronicle of Hydatius is the main source for the history of the Suebi in Galicia and Portugal up to 468.

- Identity and Interaction: the Suevi and the Hispano-Romans, University of Virginia, 2007

- Medieval Galician anthroponomy

- Minutes of the Councils of Braga and Toledo, in the Collectio Hispana Gallica Augustodunensis

- Orosius' Historiarum Adversum Paganos Libri VII

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||