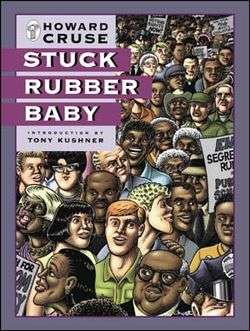

Stuck Rubber Baby

| Stuck Rubber Baby | |

|---|---|

| |

| Creator | Howard Cruse |

| Date | 1995 |

| Page count | 210 pages |

| Publisher | Paradox Press |

Stuck Rubber Baby is a graphic novel by American cartoonist Howard Cruse, first published in 1995. Cruse's first graphic novel after a decades-long career as an underground cartoonist, the book deals with homosexuality and racism in the 1960s in the Southern United States in the midst of the Civil Rights movement.

Background

Howard Cruse (b. 1944) was born in Alabama to a Baptist preacher. He earned a degree in drama and worked in television before turning to a cartooning career. From 1971 he published a strip called Barefootz that appeared in a number of underground comix publications, including three issues under its own title—though Cruse's contemporaries gave it little regard, deeming it too cute and gentle compared to the countercultural works alongside which it ran. In 1976, the openly gay Cruse introduced a gay character into the strip, committing to the gay liberation movement.[1]

In 1979 Denis Kitchen of Kitchen Sink Press invited Cruse to edit the comic-book anthology Gay Comix; the first isssue appeared in 1980.[1] From 1983[2] Cruse provided an ongoing humorous comic strip called Wendel for the LGBT magazine The Advocate.[3]

Publication

Paradox Press, an imprint of DC Comics, contracted Cruse and gave him an advance against royalties to cover expenses for the two years projected to finish the book. Cruse ultimately took four years, and when his finances became tight he took time away from the book to raise funds by applying for grants and selling page from the book before they were drawn.[4]

The book was originally intended for publication through Piranha Press, an imprint of DC Comics which published alternative comics. During that time the imprint was discontinued. It was instead published in hardcover as part of DC's Paradox Press line, an imprint aimed at the bookstore market, featuring mostly mysteries, crime fiction, and humorous non-fiction.

Stuck Rubber Baby runs 210 pages.[5] Playwright Tony Kushner wrote an introduction to the first edition; he and Cruse had met socially.[3] It was reprinted in paperback in 1996 by HarperCollins.

The book came back in print in 2010 under Vertigo, another DC imprint for mature readers, as Paradox was by then defunct. Cartoonist Alison Bechdel wrote the introduction to the new edition.[6]

Summary

Decades after the book's events, the forty-something[7] Toland Polk narrates his youth in the fictional town of Clayfield in American South in the 1950s and 1960s.[6] After his parents die in a car accident,[5] he finds he has no direction and chooses to work for a gas station rather than go to college. He becomes involved with the black population and the Civil Rights Movement, and courts a folk singer named Ginger in the hopes of curing his homosexuality; together they have a child they give up for adoption.[6]

Toland finds the black community more accepting of his homosexuality than his own white community. The bombing of a black community center, the lynching of a gay friend, and other such events push him to social activism.[6]

Style and analysis

The dense black-and-white artwork is more restrained and less cartoony than that of Cruse's earlier work.[8] Cruse abandons his trademark stippling for heavily crosshatching.[6] He gives particular attention to buildings and other background details, and to rendering characters with individuality. The pages are heavy with dialogue balloons.[8]

The frame story, set off with rounded panel borders, takes place in the late 1980s or early 1990s, as Toland narrates with his male partner by his side. The narration appears to occur over a substantial span of time, as the pair's clothing and background moves from summery to wintery.[9]

Overview

The story is not autobiographical, but does draw from Cruse's experiences growing up in Birmingham, Alabama.[10] He also includes such historical events as the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing and the murder of Emmett Till.[11] In an interview with Comic Book Resources, Cruse said that the story drew on his own experiences in the 1960s and his "anger at the degree to which the ideals of the Civil Rights Era were being abandoned."[3]

The book is densely illustrated, using a detailed cross-hatching technique and typically 8–12 panels per page. The story is 210 pages long.

Character List

- Toland Polk is the main character/Protagonist

- Melanie is Toland Polk's (the main character/Protagonist) sister

- Orley is Melanie’s Husband

- Stetson is Toland's family's old handyman/gardener, an African American

- Ben is Stetson's son who is also African American

- Ginger Raines is Toland's old Girlfriend

- Riley Wheeler is old Toland's Friend

- Mavis Greene is Riley's Girlfriend

- Sammy Noone is an old friend of Mavis & Riley who is gay

- Shiloh Reed is a singer who suffers from brain damage from an accident

- Lottie is Shiloh's wife, who has cancer

- Sledge Rankin a black person who has died from a clan

- Robert Samson is a Friend Bi-sexual Lover

- Mabel Older a piano player

- Cindy Neuworth - Mabel's younger "Butchy" girlfriend

- Marge a gay woman

- Effie is Marge's gay lover

- Reverend Harland Pepper is the town’s Preacher

- Father Edgar Morris another town Preacher

- Anna Dellyne Pepper is the Preacher's Wife

- Lester Pepper is the Gay son of the Preacher

Chapter Summary

- Chapter 1: Toland looks at a magazine and gets phobia about African-Americans with caved-in heads. Toland and Melanie pack up the books of their deceased father.

- Chapter 2: Toland is drafted in to the army and has a flashback of camp memories as they continue to pack up their father's books.

- Chapter 3: Toland gets introduced to the book. Sammy gets kicked out the Navy for being gay but still wears the uniform. There is a Carry Home protest.

- Chapter 4: Mavis is accused of flirting with Mabel by Cindy. Cindy apologizes. A party occurs with gays and black all together in one room.

- Chapter 5: Riley invites Toland to move into Wheelery after he returns from the Army. Orley calls Rhombus a "fag bar," and leaves early with Melanie.

- Chapter 6:

- Chapter 7:

- Chapter 8:

- Chapter 9:

- Chapter 10:

- Chapter 11:

- Chapter 12:

- Chapter 13:

- Chapter 14:

- Chapter 15:

- Chapter 16:

- Chapter 17:

- Chapter 18:

- Chapter 19:

- Chapter 20:

- Chapter 21:

- Chapter 22:

- Chapter 23:

- Chapter 24:

Reception and legacy

Stuck Rubber Baby appeared among high expectations generated by the success of Art Spiegelman's Maus, completed in 1991.[12] Stuck Rubber Baby won the award for Best Graphic Novel at both the Einsers, Harveys.[8] and UK Comic Art Awards. It was nominated for the American Library Association's Lesbian and Gay Book Award and the Lambda Literary Award. It won the 2002 French Prix de la critique and the Luche award in Germany.[13]

Comics writer Harvey Pekar wrote that, if enough people read it, "it surely will help convince the general public that comics can appeal to adults."[2] Upon its reprinting in 2011, Comics Alliance wrote that Cruse "harnessed a symphony of discordant subtleties."[14] The book has generated some controversy; in 2004, a Texas citizens' group asked that it be removed from the young adult section of the local library.[15]

Cruse's earlier work influenced Alison Bechdel in her comic strip Dykes to Watch Out For, and she later produced the graphic novels Fun Home (2006) and Are You My Mother? (2012) which also treat grappling with homosexual awakening.[8]

References

- 1 2 Booker 2014, p. 979.

- 1 2 Pekar 1995.

- 1 2 3 Dueben 2011.

- ↑ Hatfield 2005, p. 161.

- 1 2 Worcester 2010, p. 602.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Kohlert 2014, p. 1769.

- ↑ Dickel 2011, p. 617.

- 1 2 3 4 Kohlert 2014, p. 1770.

- ↑ Dickel 2011, pp. 617–618.

- ↑ Kohlert 2014, p. 1769; Dueben 2011.

- ↑ Dickel 2011, p. 618.

- ↑ Hatfield 2005, pp. 161–162.

- ↑ Worcester 2010, pp. 601–602.

- ↑ Warmoth, Brian. "Comics We Love: Howard Cruse's 'Stuck Rubber Baby' in Print Again, At Last". Comics Alliance. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- ↑ Oder, Norman. "Group lists 119 books it wants moved, file requests on 20". Library Journal. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

Works cited

- Dickel, Simon (2011). ""Can't Leave Me Behind": Racism, Gay Politics, and Coming of Age in Howard Cruse's "Stuck Rubber Baby"". Amerikastudien / American Studies (Universitätsverlag WINTER Gmbh) 56 (4): 617–635. JSTOR 23509432.

- Dueben, Alex (2011-06-23). "Cruse Returns with "The Complete Wendel"". Comic Book Resources. Archived from the original on 2011-06-30. Retrieved 2013-03-12.

- Hatfield, Charles (2005). Alternative Comics: An Emerging Literature. University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 978-1-60473-587-1 – via Project MUSE. (subscription required (help)).

- Kohlert, Frederik Byrn (2014). "Stuck Rubber Baby". In Booker, M. Keith. Comics through Time: A History of Icons, Idols, and Ideas. ABC-CLIO. pp. 1769–1770. ISBN 978-0-313-39751-6.

- Booker, M. Keith, ed. (2014). "Howard Cruse". Comics through Time: A History of Icons, Idols, and Ideas. ABC-CLIO. pp. 979–980. ISBN 978-0-313-39751-6.

- Pekar, Harvey (1995-12-03). "Compelling Comic Howard Cruse's 'Graphic Novel' Of Serious Concerns". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on 2015-04-14. Retrieved 2015-04-14.

- Worcester, Kent (2010). "Stuck Rubber Baby". In Booker, M. Keith. Encyclopedia of Comic Books and Graphic Novels: [Two Volumes]. ABC-CLIO. pp. 601–603. ISBN 978-0-313-35747-3.

Further reading

- The Comics Journal #182, pp. 93–118, Fantagraphics, November 1995. A critical overview of Stuck Rubber Baby, with an interview of Howard Cruse.