Stream function

The stream function is defined for incompressible (divergence-free) flows in two dimensions – as well as in three dimensions with axisymmetry. The flow velocity components can then be expressed as the derivatives of the scalar stream function. The stream function can be used to plot streamlines, which represent the trajectories of particles in a steady flow. The two-dimensional Lagrange stream function was introduced by Joseph Louis Lagrange in 1781.[1] The Stokes stream function is for axisymmetrical three-dimensional flow, and is named after George Gabriel Stokes.[2]

Considering the particular case of fluid dynamics, the difference between the stream function values at any two points gives the volumetric flow rate (or volumetric flux) through a line connecting the two points.

Since streamlines are tangent to the flow velocity vector of the flow, the value of the stream function must be constant along a streamline. The usefulness of the stream function lies in the fact that the flow velocity components in the x- and y- directions at a given point are given by the partial derivatives of the stream function at that point. A stream function may be defined for any flow of dimensions greater than or equal to two, however the two-dimensional case is generally the easiest to visualize and derive.

For two-dimensional potential flow, streamlines are perpendicular to equipotential lines. Taken together with the velocity potential, the stream function may be used to derive a complex potential. In other words, the stream function accounts for the solenoidal part of a two-dimensional Helmholtz decomposition, while the velocity potential accounts for the irrotational part.

Two-dimensional stream function

Definitions

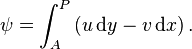

Lamb and Batchelor define the stream function  – in the point

– in the point  with two-dimensional coordinates

with two-dimensional coordinates  and as a function of time

and as a function of time  – for an incompressible flow by:[3]

– for an incompressible flow by:[3]

So the stream function  is the volume flux through the curve

is the volume flux through the curve  , that is: the integral of the dot product of the flow velocity vector

, that is: the integral of the dot product of the flow velocity vector  and the normal

and the normal  to the curve element

to the curve element  The point

The point  is a reference point defining where the stream function is zero: a shift of

is a reference point defining where the stream function is zero: a shift of  results in adding a constant to the stream function

results in adding a constant to the stream function

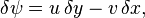

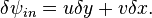

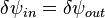

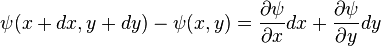

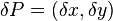

An infinitesimal shift  of the position

of the position  results in a stream function shift:

results in a stream function shift:

which is an exact differential provided

This is the condition of zero divergence resulting from flow incompressibility. Since

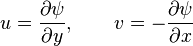

the flow velocity components have to be

and

and

in relation to the stream function

Definition by use of a vector potential

The sign of the stream function depends on the definition used.

One way is to define the stream function  for a two-dimensional flow such that the flow velocity can be expressed through the vector potential

for a two-dimensional flow such that the flow velocity can be expressed through the vector potential

Where  if the flow velocity vector

if the flow velocity vector  .

.

In Cartesian coordinate system this is equivalent to

Where  and

and  are the flow velocity components in the cartesian

are the flow velocity components in the cartesian  and

and  coordinate directions, respectively.

coordinate directions, respectively.

Alternative definition (opposite sign)

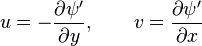

Another definition (used more widely in meteorology and oceanography than the above) is

,

,

where  is a unit vector in the

is a unit vector in the  direction and the subscripts indicate partial derivatives.

direction and the subscripts indicate partial derivatives.

Note that this definition has the opposite sign to that given above ( ), so we have

), so we have

in Cartesian coordinates.

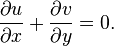

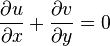

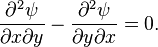

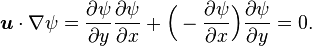

All formulations of the stream function constrain the velocity to satisfy the two-dimensional continuity equation exactly:

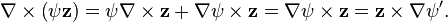

The last two definitions of stream function are related through the vector calculus identity

Note that  in this two-dimensional flow.

in this two-dimensional flow.

Derivation of the two-dimensional stream function

Consider two points A and B in two-dimensional plane flow. If the distance between these two points is very small: δn, and a stream of flow passes between these points with an average velocity, q perpendicular to the line AB, the volume flow rate per unit thickness, δΨ is given by:

As δn → 0, rearranging this expression, we get:

Now consider two-dimensional plane flow with reference to a coordinate system. Suppose an observer looks along an arbitrary axis in the direction of increase and sees flow crossing the axis from left to right. A sign convention is adopted such that the flow velocity is positive.

Flow in Cartesian coordinates

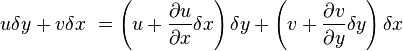

By observing the flow into an elemental square in an x-y Cartesian coordinate system, we have:

where u is the flow velocity parallel to and in the direction of the x-axis, and v is the flow velocity parallel to and in the direction of the y-axis. Thus, as δn → 0 and by rearranging, we have:

Continuity: the derivation

Consider two-dimensional plane flow within a Cartesian coordinate system. Continuity states that if we consider incompressible flow into an elemental square, the flow into that small element must equal the flow out of that element.

The total flow into the element is given by:

The total flow out of the element is given by:

Thus we have:

and simplifying to:

Substituting the expressions of the stream function into this equation, we have:

Vorticity

The stream function can be found from vorticity using the following Poisson's equation:

or

where the vorticity vector  – defined as the curl of the flow velocity vector

– defined as the curl of the flow velocity vector  – for this two-dimensional flow has

– for this two-dimensional flow has  i.e. only the

i.e. only the  -component

-component  can be non-zero.

can be non-zero.

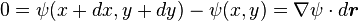

Proof that a constant value for the stream function corresponds to a streamline

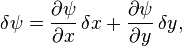

Consider two-dimensional plane flow within a Cartesian coordinate system. Consider two infinitesimally close points  and

and  . From calculus we have that

. From calculus we have that

Say  takes the same value, say

takes the same value, say  , at the two points

, at the two points  and

and  , then

, then  is tangent to the curve

is tangent to the curve  at

at  and

and

implying that the vector  is normal to the curve

is normal to the curve  . If we can show that everywhere

. If we can show that everywhere  , using the formula for

, using the formula for  in terms of

in terms of  , then we will have proved the result. This easily follows,

, then we will have proved the result. This easily follows,

References

Inline

- ↑ Lagrange, J.-L. (1868), "Mémoire sur la théorie du mouvement des fluides (in: Nouveaux Mémoires de l'Académie Royale des Sciences et Belles-Lettres de Berlin, année 1781)", Oevres de Lagrange, Tome IV, pp. 695–748

- ↑ Stokes, G.G. (1842), "On the steady motion of incompressible fluids", Transactions of the Cambridge Philosophical Society 7: 439–453, Bibcode:1848TCaPS...7..439S

Reprinted in: Stokes, G.G. (1880), Mathematical and Physical Papers, Volume I, Cambridge University Press, pp. 1–16 - ↑ Lamb (1932), pp. 62–63 and Batchelor (1967), pp. 75–79

Other

- Batchelor, G. K. (1967), An Introduction to Fluid Dynamics, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-09817-3

- Lamb, H. (1932), Hydrodynamics (6th ed.), Cambridge University Press, republished by Dover Publications, ISBN 0-486-60256-7

- Massey, B. S.; Ward-Smith, J. (1998), Mechanics of Fluids (7th ed.), UK: Nelson Thornes

- White, F. M. (2003), Fluid Mechanics (5th ed.), New York: McGraw-Hill

- Gamelin, T. W. (2001), Complex Analysis, New York: Springer, ISBN 0-387-95093-1

- "Streamfunction", AMS Glossary of Meteorology (American Meteorological Society), retrieved 2014-01-30