Compass-and-straightedge construction

| Geometry | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||

| Geometers | ||||||||||

|

by name

|

||||||||||

|

by period

|

||||||||||

Compass-and-straightedge construction, also known as ruler-and-compass construction or classical construction, is the construction of lengths, angles, and other geometric figures using only an idealized ruler and compass.

The idealized ruler, known as a straightedge, is assumed to be infinite in length, and has no markings on it and only one edge. The compass is assumed to collapse when lifted from the page, so may not be directly used to transfer distances. (This is an unimportant restriction since, using a multi-step procedure, a distance can be transferred even with collapsing compass; see compass equivalence theorem.) More formally, the only permissible constructions are those granted by Euclid's first three postulates. Every point constructible using straightedge and compass may be constructed using compass alone.

The ancient Greek mathematicians first conceived compass-and-straightedge constructions, and a number of ancient problems in plane geometry impose this restriction. The ancient Greeks developed many constructions, but in some cases were unable to do so. Gauss showed that some polygons are constructible but that most are not. Some of the most famous straightedge-and-compass problems were proven impossible by Pierre Wantzel in 1837, using the mathematical theory of fields.

In spite of existing proofs of impossibility, some persist in trying to solve these problems.[1] Many of these problems are easily solvable provided that other geometric transformations are allowed: for example, doubling the cube is possible using geometric constructions, but not possible using straightedge and compass alone.

In terms of algebra, a length is constructible if and only if it represents a constructible number, and an angle is constructible if and only if its cosine is a constructible number. A number is constructible if and only if it can be written using the four basic arithmetic operations and the extraction of square roots but of no higher-order roots.

Compass and straightedge tools

The "compass" and "straightedge" of compass and straightedge constructions are idealizations of rulers and compasses in the real world:

- The compass can be opened arbitrarily wide, but (unlike some real compasses) it has no markings on it. Circles can only be drawn starting from two given points: the centre and a point on the circle. The compass may or may not collapse when it's not drawing a circle.

- The straightedge is infinitely long, but it has no markings on it and has only one straight edge, unlike ordinary rulers. It can only be used to draw a line segment between two points or to extend an existing segment.

The modern compass generally does not collapse and several modern constructions use this feature. It would appear that the modern compass is a "more powerful" instrument than the ancient collapsing compass. However, by Proposition 2 of Book 1 of Euclid's Elements, no power is lost by using a collapsing compass. Although the proposition is correct, its proofs have a long and checkered history.[2]

Each construction must be exact. "Eyeballing" it (essentially looking at the construction and guessing at its accuracy, or using some form of measurement, such as the units of measure on a ruler) and getting close does not count as a solution.

Each construction must terminate. That is, it must have a finite number of steps, and not be the limit of ever closer approximations.

Stated this way, compass and straightedge constructions appear to be a parlour game, rather than a serious practical problem; but the purpose of the restriction is to ensure that constructions can be proven to be exactly correct, and is thus important to both drafting (design by both CAD software and traditional drafting with pencil, paper, straight-edge and compass) and the science of weights and measures, in which exact synthesis from reference bodies or materials is extremely important. One of the chief purposes of Greek mathematics was to find exact constructions for various lengths; for example, the side of a pentagon inscribed in a given circle. The Greeks could not find constructions for these three problems, among others:

- Squaring the circle: Drawing a square the same area as a given circle.

- Doubling the cube: Drawing a cube with twice the volume of a given cube.

- Trisecting the angle: Dividing a given angle into three smaller angles all of the same size.

For 2000 years people tried to find constructions within the limits set above, and failed. All three have now been proven under mathematical rules to be impossible generally (angles with certain values can be trisected, but not all possible angles).

History

The ancient Greek mathematicians first attempted compass-and-straightedge constructions, and they discovered how to construct sums, differences, products, ratios, and square roots of given lengths.[3]:p. 1 They could also construct half of a given angle, a square whose area is twice that of another square, a square having the same area as a given polygon, and a regular polygon with 3, 4, or 5 sides[3]:p. xi (or one with twice the number of sides of a given polygon[3]:pp. 49–50). But they could not construct one third of a given angle except in particular cases, or a square with the same area as a given circle, or a regular polygon with other numbers of sides.[3]:p. xi Nor could they construct the side of a cube whose volume would be twice the volume of a cube with a given side.[3]:p. 29

Hippocrates and Menaechmus showed that the area of the cube could be doubled by finding the intersections of hyperbolas and parabolas, but these cannot be constructed by compass and straightedge.[3]:p. 30 In the fifth century BCE, Hippias used a curve that he called a quadratrix to both trisect the general angle and square the circle, and Nicomedes in the second century BCE showed how to use a conchoid to trisect an arbitrary angle;[3]:p. 37 but these methods also cannot be followed with just compass and straightedge.

No progress on the unsolved problems was made for two millennia, until in 1796 Gauss showed that a regular polygon with 17 sides could be constructed; five years later he showed the sufficient criterion for a regular polygon of n sides to be constructible.[3]:pp. 51 ff.

In 1837 Pierre Wantzel published a proof of the impossibility of trisecting an arbitrary angle or of doubling the volume of a cube, based on the impossibility of constructing cube roots of lengths.[4] He also showed that Gauss's sufficient constructibility condition for regular polygons is also necessary.

Then in 1882 Lindemann showed that  is a transcendental number, and thus that it is impossible by straightedge and compass to construct a square with the same area as a given circle.[3]:p. 47

is a transcendental number, and thus that it is impossible by straightedge and compass to construct a square with the same area as a given circle.[3]:p. 47

The basic constructions

All compass and straightedge constructions consist of repeated application of five basic constructions using the points, lines and circles that have already been constructed. These are:

- Creating the line through two existing points

- Creating the circle through one point with centre another point

- Creating the point which is the intersection of two existing, non-parallel lines

- Creating the one or two points in the intersection of a line and a circle (if they intersect)

- Creating the one or two points in the intersection of two circles (if they intersect).

For example, starting with just two distinct points, we can create a line or either of two circles (in turn, using each point as centre and passing through the other point). If we draw both circles, two new points are created at their intersections. Drawing lines between the two original points and one of these new points completes the construction of an equilateral triangle.

Therefore, in any geometric problem we have an initial set of symbols (points and lines), an algorithm, and some results. From this perspective, geometry is equivalent to an axiomatic algebra, replacing its elements by symbols. Probably Gauss first realized this, and used it to prove the impossibility of some constructions; only much later did Hilbert find a complete set of axioms for geometry.

Much used compass-and-straightedge constructions

The most-used compass-and-straightedge constructions include:

- Constructing the perpendicular bisector from a segment

- Finding the midpoint of a segment.

- Drawing a perpendicular line from a point to a line.

- Bisecting an angle

- Mirror a point in a line

- construct line through a point tangent to a circle

Constructible points and lengths

Formal proof

There are many different ways to prove something is impossible. A more rigorous proof would be to demarcate the limit of the possible, and show that to solve these problems one must transgress that limit. Much of what can be constructed is covered in intercept theory.

We could associate an algebra to our geometry using a Cartesian coordinate system made of two lines, and represent points of our plane by vectors. Finally we can write these vectors as complex numbers.

Using the equations for lines and circles, one can show that the points at which they intersect lie in a quadratic extension of the smallest field F containing two points on the line, the center of the circle, and the radius of the circle. That is, they are of the form  , where x, y, and k are in F.

, where x, y, and k are in F.

Since the field of constructible points is closed under square roots, it contains all points that can be obtained by a finite sequence of quadratic extensions of the field of complex numbers with rational coefficients. By the above paragraph, one can show that any constructible point can be obtained by such a sequence of extensions. As a corollary of this, one finds that the degree of the minimal polynomial for a constructible point (and therefore of any constructible length) is a power of 2. In particular, any constructible point (or length) is an algebraic number, though not every algebraic number is constructible (i.e. the relationship between constructible lengths and algebraic numbers is not bijective); for example, ![\sqrt[3]{2}](../I/m/62f6a0ce6cf44d89c6f3b211c98c43bd.png) is algebraic but not constructible.

is algebraic but not constructible.

Constructible angles

There is a bijection between the angles that are constructible and the points that are constructible on any constructible circle. The angles that are constructible form an abelian group under addition modulo 2π (which corresponds to multiplication of the points on the unit circle viewed as complex numbers). The angles that are constructible are exactly those whose tangent (or equivalently, sine or cosine) is constructible as a number. For example the regular heptadecagon (the seventeen-sided regular polygon) is constructible because

The group of constructible angles is closed under the operation that halves angles (which corresponds to taking square roots in the complex numbers). The only angles of finite order that may be constructed starting with two points are those whose order is either a power of two, or a product of a power of two and a set of distinct Fermat primes. In addition there is a dense set of constructible angles of infinite order.

Compass and straightedge constructions as complex arithmetic

Given a set of points in the Euclidean plane, selecting any one of them to be called 0 and another to be called 1, together with an arbitrary choice of orientation allows us to consider the points as a set of complex numbers.

Given any such interpretation of a set of points as complex numbers, the points constructible using valid compass and straightedge constructions alone are precisely the elements of the smallest field containing the original set of points and closed under the complex conjugate and square root operations (to avoid ambiguity, we can specify the square root with complex argument less than π). The elements of this field are precisely those that may be expressed as a formula in the original points using only the operations of addition, subtraction, multiplication, division, complex conjugate, and square root, which is easily seen to be a countable dense subset of the plane. Each of these six operations corresponding to a simple compass and straightedge construction. From such a formula it is straightforward to produce a construction of the corresponding point by combining the constructions for each of the arithmetic operations. More efficient constructions of a particular set of points correspond to shortcuts in such calculations.

Equivalently (and with no need to arbitrarily choose two points) we can say that, given an arbitrary choice of orientation, a set of points determines a set of complex ratios given by the ratios of the differences between any two pairs of points. The set of ratios constructible using compass and straightedge from such a set of ratios is precisely the smallest field containing the original ratios and closed under taking complex conjugates and square roots.

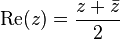

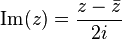

For example the real part, imaginary part and modulus of a point or ratio z (taking one of the two viewpoints above) are constructible as these may be expressed as

Doubling the cube and trisection of an angle (except for special angles such as any φ such that φ/2π is a rational number with denominator not divisible by 3) require ratios which are the solution to cubic equations, while squaring the circle requires a transcendental ratio. None of these are in the fields described, hence no compass and straightedge construction for these exists.

Impossible constructions

The ancient Greeks thought that the construction problems they could not solve were simply obstinate, not unsolvable.[6] With modern methods, however, these compass-and-straightedge constructions have been shown to be logically impossible to perform. (The problems themselves, however, are solvable, and the Greeks knew how to solve them, without the constraint of working only with straightedge and compass.)

Squaring the circle

The most famous of these problems, squaring the circle, otherwise known as the quadrature of the circle, involves constructing a square with the same area as a given circle using only straightedge and compass.

Squaring the circle has been proven impossible, as it involves generating a transcendental number, that is,  . Only certain algebraic numbers can be constructed with ruler and compass alone, namely those constructed from the integers with a finite sequence of operations of addition, subtraction, multiplication, division, and taking square roots. The phrase "squaring the circle" is often used to mean "doing the impossible" for this reason.

. Only certain algebraic numbers can be constructed with ruler and compass alone, namely those constructed from the integers with a finite sequence of operations of addition, subtraction, multiplication, division, and taking square roots. The phrase "squaring the circle" is often used to mean "doing the impossible" for this reason.

Without the constraint of requiring solution by ruler and compass alone, the problem is easily solvable by a wide variety of geometric and algebraic means, and has been solved many times in antiquity.[7]

Doubling the cube

Doubling the cube: using only a straight-edge and compass, construct the edge of a cube that has twice the volume of a cube with a given edge. This is impossible because the cube root of 2, though algebraic, cannot be computed from integers by addition, subtraction, multiplication, division, and taking square roots. This follows because its minimal polynomial over the rationals has degree 3. This construction is possible using a straightedge with two marks on it and a compass.

Angle trisection

Angle trisection: using only a straightedge and a compass, construct an angle that is one-third of a given arbitrary angle. This is impossible in the general case. For example: though the angle of π/3 radians (60°) cannot be trisected, the angle 2π/5 radians (72° = 360°/5) can be trisected. This problem is also easily solved when a straightedge with two marks on it is allowed (a neusis construction).

Constructing regular polygons

Some regular polygons (e.g. a pentagon) are easy to construct with straightedge and compass; others are not. This led to the question: Is it possible to construct all regular polygons with straightedge and compass?

Carl Friedrich Gauss in 1796 showed that a regular 17-sided polygon can be constructed, and five years later showed that a regular n-sided polygon can be constructed with straightedge and compass if the odd prime factors of n are distinct Fermat primes. Gauss conjectured that this condition was also necessary, but he offered no proof of this fact, which was provided by Pierre Wantzel in 1837.[8]

The first few constructible regular polygons are:[9]

- 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, 10, 12, 15, 16, 17, 20, 24, 30, 32, 34, 40, 48, 51, 60, 64, 68, 80, 85, 96, 102, 120, 128, 136, 160, 170, 192, 204, 240, 255, 256, 257, 272... (sequence A003401 in OEIS)

Distance to an ellipse

The line segment from any point in the plane to the nearest point on a circle can be constructed, but the segment from any point in the plane to the nearest point on an ellipse of positive eccentricity cannot in general be constructed.[10]

Constructing with only ruler or only compass

It is possible (according to the Mohr–Mascheroni theorem) to construct anything with just a compass if it can be constructed with a ruler and compass, provided that the given data and the data to be found consist of discrete points (not lines or circles). It is impossible to take a square root with just a ruler, so some things that cannot be constructed with a ruler can be constructed with a compass; but (by the Poncelet–Steiner theorem) given a single circle and its center, they can be constructed.

Extended constructions

In abstract terms, using these more powerful tools of either neusis using a markable ruler or the constructions of origami extends the field of constructible numbers to a larger subfield of the complex numbers, which contains not only the square root, but also the cube roots, of every element. The arithmetic formulae for constructible points described above have analogies in this larger field, allowing formulae that include cube roots as well. The field extension generated by any additional point constructible in this larger field has degree a multiple of a power of two and a power of three, and may be broken into a tower of extensions of degree 2 and 3.

Markable rulers

Archimedes and Apollonius gave constructions involving the use of a markable ruler. This would permit them, for example, to take a line segment, two lines (or circles), and a point; and then draw a line which passes through the given point and intersects both lines, and such that the distance between the points of intersection equals the given segment. This the Greeks called neusis ("inclination", "tendency" or "verging"), because the new line tends to the point. In this expanded scheme, any distance whose ratio to an existing distance is the solution of a cubic or a quartic equation is constructible. It follows that, if markable rulers and neusis are permitted, the trisection of the angle (see Archimedes' trisection) and the duplication of the cube can be achieved; the quadrature of the circle is still impossible. Some regular polygons, like the heptagon, become constructible; and John H. Conway gives constructions for several of them;[11] but the 11-sided polygon, the hendecagon, is still impossible, and infinitely many others.

When only an angle trisector is permitted, there is a complete description of all regular polygons which can be constructed, including above mentioned regular heptagon, triskaidecagon (13-gon) and enneadecagon (19-gon).[12] It is open whether there are infinitely many primes p for which a regular p-gon is constructible with ruler, compass and an angle trisector (Pierpont primes).

Allowing the use of neusis or angle trisector makes the following additional regular polygons also constructible:[9]

- 7, 9, 13, 14, 18, 19, 21, 26, 27, 28, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 42, 45, 52, 54, 56, 57, 63, 65, 70, 72, 73, 74, 76, 78, 81, 84, 90, 91, 95, 97... (sequence A051913 in OEIS)

The first few regular polygons not constructible even allowing neusis or angle trisector are:

- 11, 22, 23, 25, 29, 31, 33, 41, 43, 44, 46, 47, 49, 50, 53, 55, 58, 59, 61, 62, 66, 67, 69, 71, 75, 77, 79, 82, 83, 86, 87, 88, 89, 92, 93, 94, 98, 99, 100... (sequence A048136 in OEIS)

Origami

The mathematical theory of origami is more powerful than compass and straightedge construction. Folds satisfying the Huzita–Hatori axioms can construct exactly the same set of points as the extended constructions using a compass and a marked ruler. Therefore origami can also be used to solve cubic equations (and hence quartic equations), and thus solve two of the classical problems.[13]

Computation of binary digits

In 1998 Simon Plouffe gave a ruler and compass algorithm that can be used to compute binary digits of certain numbers.[14] The algorithm involves the repeated doubling of an angle and becomes physically impractical after about 20 binary digits.

See also

- Constructible number

- Constructible polygon

- Carlyle circle

- Geometric cryptography

- Geometrography

- Interactive geometry software may allow the user to create and manipulate ruler-and-compass constructions.

- List of interactive geometry software, most of them show compass and straightedge constructions

- Mohr–Mascheroni theorem

- Poncelet–Steiner theorem

- Underwood Dudley, a mathematician that has made a sideline of collecting false ruler-and-compass proofs.

References

- ↑ Underwood Dudley (1983), "What To Do When the Trisector Comes" (PDF), The Mathematical Intelligencer 5 (1): 20–25, doi:10.1007/bf03023502

- ↑ Godfried Toussaint, "A new look at Euclid’s second proposition," The Mathematical Intelligencer, Vol. 15, No. 3, (1993), pp. 12-24.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Bold, Benjamin. Famous Problems of Geometry and How to Solve Them, Dover Publications, 1982 (orig. 1969).

- ↑ Wantzel, P M L (1837). "Recherches sur les moyens de reconnaître si un problème de Géométrie peut se résoudre avec la règle et le compas." (PDF). Journal de Mathématiques Pures et Appliquées. 1 2: 366–372. Retrieved 3 March 2014.

- ↑ Weisstein, Eric W., "Trigonometry Angles--Pi/17", MathWorld.

- ↑ Stewart, Ian. Galois Theory. p. 75.

- ↑

- ↑ Kazarinoff, Nicholas D. (2003). Ruler and the Round. Mineola, N.Y.: Dover. pp. 29–30. ISBN 0-486-42515-0.

- 1 2 http://www.math.iastate.edu/thesisarchive/MSM/EekhoffMSMSS07.pdf

- ↑ Azad, H., and Laradji, A., "Some impossible constructions in elementary geometry", Mathematical Gazette 88, November 2004, 548–551.

- ↑ Conway, John H. and Richard Guy: The Book of Numbers

- ↑ Gleason, Andrew: "Angle trisection, the heptagon, and the triskaidecagon", Amer. Math. Monthly 95 (1988), no. 3, 185-194.

- ↑ Row, T. Sundara (1966). Geometric Exercises in Paper Folding. New York: Dover.

- ↑ Simon Plouffe (1998). "The Computation of Certain Numbers Using a Ruler and Compass". Journal of Integer Sequences 1. ISSN 1530-7638.

External links

- Online ruler-and-compass construction tool (in French)

- Regular polygon constructions by Dr. Math at The Math Forum @ Drexel

- Construction with the Compass Only at cut-the-knot

- Angle Trisection by Hippocrates at cut-the-knot

- Weisstein, Eric W., "Angle Trisection", MathWorld.

- Various constructions using compass and straightedge With interactive animated step-by-step instructions

- Math Tricks Help You Design Shop Projects: master a simple compass and you're a designer; convert your router into one with a trammel and away you go, Popular Science, May 1971, p104,106,108, Scanned article via Google Books: http://books.google.com/books?id=ngAAAAAAMBAJ&pg=PA104

- Visual Euclid slideshows of Euclidean constructions

- The Golden Ratio Determined Using a Ruler and Compass list of all the shortest constructions