Stochastic game

In game theory, a stochastic game, introduced by Lloyd Shapley in the early 1950s, is a dynamic game with probabilistic transitions played by one or more players. The game is played in a sequence of stages. At the beginning of each stage the game is in some state. The players select actions and each player receives a payoff that depends on the current state and the chosen actions. The game then moves to a new random state whose distribution depends on the previous state and the actions chosen by the players. The procedure is repeated at the new state and play continues for a finite or infinite number of stages. The total payoff to a player is often taken to be the discounted sum of the stage payoffs or the limit inferior of the averages of the stage payoffs.

Stochastic games generalize both Markov decision processes and repeated games.

Two-player games

Stochastic two-player games on directed graphs are widely used for modeling and analysis of discrete systems operating in an unknown (adversarial) environment. Possible configurations of a system and its environment are represented as vertices, and the transitions correspond to actions of the system, its environment, or "nature". A run of the system then corresponds to an infinite path in the graph. Thus, a system and its environment can be seen as two players with antagonistic objectives, where one player (the system) aims at maximizing the probability of "good" runs, while the other player (the environment) aims at the opposite.

In many cases, there exists an equilibrium value of this probability, but optimal strategies for both players may not exist.

We introduce basic concepts and algorithmic questions studied in this area, and we mention some long-standing open problems. Then, we mention selected recent results.

Theory

The ingredients of a stochastic game are: a finite set of players  ; a state space

; a state space  (either a finite set or a measurable space

(either a finite set or a measurable space  ); for each player

); for each player  , an action set

, an action set  (either a finite set or a measurable space

(either a finite set or a measurable space  ); a transition probability

); a transition probability  from

from  , where

, where  is the action profiles, to

is the action profiles, to  , where

, where  is the probability that the next state is in

is the probability that the next state is in  given the current state

given the current state  and the current action profile

and the current action profile  ; and a payoff function

; and a payoff function  from

from  to

to  , where the

, where the  -th coordinate of

-th coordinate of  ,

,  , is the payoff to player

, is the payoff to player  as a function of the state

as a function of the state  and the action profile

and the action profile  .

.

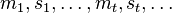

The game starts at some initial state  . At stage

. At stage  , players first observe

, players first observe  , then simultaneously choose actions

, then simultaneously choose actions  , then observe the action profile

, then observe the action profile  , and then nature selects

, and then nature selects  according to the probability

according to the probability  . A play of the stochastic game,

. A play of the stochastic game,  ,

defines a stream of payoffs

,

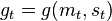

defines a stream of payoffs  , where

, where  .

.

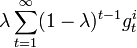

The discounted game  with discount factor

with discount factor  (

( ) is the game where the payoff to player

) is the game where the payoff to player  is

is  . The

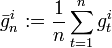

. The  -stage game

is the game where the payoff to player

-stage game

is the game where the payoff to player  is

is  .

.

The value  , respectively

, respectively  , of a two-person zero-sum stochastic game

, of a two-person zero-sum stochastic game  , respectively

, respectively  , with finitely many states and actions exists, and Truman Bewley and Elon Kohlberg (1976) proved that

, with finitely many states and actions exists, and Truman Bewley and Elon Kohlberg (1976) proved that  converges to a limit as

converges to a limit as  goes to infinity and that

goes to infinity and that  converges to the same limit as

converges to the same limit as  goes to

goes to  .

.

The "undiscounted" game  is the game where the payoff to player

is the game where the payoff to player  is the "limit" of the averages of the stage payoffs. Some precautions are needed in defining the value of a two-person zero-sum

is the "limit" of the averages of the stage payoffs. Some precautions are needed in defining the value of a two-person zero-sum  and in defining equilibrium payoffs of a non-zero-sum

and in defining equilibrium payoffs of a non-zero-sum  . The uniform value

. The uniform value  of a two-person zero-sum stochastic game

of a two-person zero-sum stochastic game  exists if for every

exists if for every  there is a positive integer

there is a positive integer  and a strategy pair

and a strategy pair  of player 1 and

of player 1 and  of player 2 such that for every

of player 2 such that for every  and

and  and every

and every  the expectation of

the expectation of  with respect to the probability on plays defined by

with respect to the probability on plays defined by  and

and  is at least

is at least  , and the expectation of

, and the expectation of  with respect to the probability on plays defined by

with respect to the probability on plays defined by  and

and  is at most

is at most  . Jean-François Mertens and Abraham Neyman (1981) proved that every two-person zero-sum stochastic game with finitely many states and actions has a uniform value.

. Jean-François Mertens and Abraham Neyman (1981) proved that every two-person zero-sum stochastic game with finitely many states and actions has a uniform value.

If there is a finite number of players and the action sets and the set of states are finite, then a stochastic game with a finite number of stages always has a Nash equilibrium. The same is true for a game with infinitely many stages if the total payoff is the discounted sum.

The non-zero-sum stochastic game  has a uniform equilibrium payoff

has a uniform equilibrium payoff  if for every

if for every  there is a positive integer

there is a positive integer  and a strategy profile

and a strategy profile  such that for every unilateral deviation by a player

such that for every unilateral deviation by a player  , i.e., a strategy profile

, i.e., a strategy profile  with

with  for all

for all  , and every

, and every  the expectation of

the expectation of  with respect to the probability on plays defined by

with respect to the probability on plays defined by  is at least

is at least  , and the expectation of

, and the expectation of  with respect to the probability on plays defined by

with respect to the probability on plays defined by  is at most

is at most  . Nicolas Vieille has shown that all two-person stochastic games with finite state and action spaces have a uniform equilibrium payoff.

. Nicolas Vieille has shown that all two-person stochastic games with finite state and action spaces have a uniform equilibrium payoff.

The non-zero-sum stochastic game  has a limiting-average equilibrium payoff

has a limiting-average equilibrium payoff  if for every

if for every  there is a strategy profile

there is a strategy profile  such that for every unilateral deviation by a player

such that for every unilateral deviation by a player  , the expectation of the limit inferior of the averages of the stage payoffs with respect to the probability on plays defined by

, the expectation of the limit inferior of the averages of the stage payoffs with respect to the probability on plays defined by  is at least

is at least  , and the expectation of the limit superior of the averages of the stage payoffs with respect to the probability on plays defined by

, and the expectation of the limit superior of the averages of the stage payoffs with respect to the probability on plays defined by  is at most

is at most  . Jean-François Mertens and Abraham Neyman (1981) proves that every two-person zero-sum stochastic game with finitely many states and actions has a limiting-average value, and Nicolas Vieille has shown that all two-person stochastic games with finite state and action spaces have a limiting-average equilibrium payoff. In particular, these results imply that these games have a value and an approximate equilibrium payoff, called the liminf-average (respectively, the limsup-average) equilibrium payoff, when the total payoff is the limit inferior (or the limit superior) of the averages of the stage payoffs.

. Jean-François Mertens and Abraham Neyman (1981) proves that every two-person zero-sum stochastic game with finitely many states and actions has a limiting-average value, and Nicolas Vieille has shown that all two-person stochastic games with finite state and action spaces have a limiting-average equilibrium payoff. In particular, these results imply that these games have a value and an approximate equilibrium payoff, called the liminf-average (respectively, the limsup-average) equilibrium payoff, when the total payoff is the limit inferior (or the limit superior) of the averages of the stage payoffs.

Whether every stochastic game with finitely many players, states, and actions, has a uniform equilibrium payoff, or a limiting-average equilibrium payoff, or even a liminf-average equilibrium payoff, is a challenging open question.

A Markov perfect equilibrium is a refinement of the concept of sub-game perfect Nash equilibrium to stochastic games..

Applications

Stochastic games have applications in economics, evolutionary biology and computer networks.[1] They are generalizations of repeated games which correspond to the special case where there is only one state.

Referring book

The most complete reference is the book of articles edited by Neyman and Sorin. The more elementary book of Filar and Vrieze provides a unified rigorous treatment of the theories of Markov Decision Processes and two-person stochastic games. They coin the term Competitive MDPs to encompass both one- and two-player stochastic games.

External links

Notes

- ↑ Constrained Stochastic Games in Wireless Networks by E.Altman, K.Avratchenkov, N.Bonneau, M.Debbah, R.El-Azouzi, D.S.Menasche

Further reading

- Condon, A. (1992). "The complexity of stochastic games". Information and Computation 96: 203–224. doi:10.1016/0890-5401(92)90048-K.

- H. Everett (1957). "Recursive games". In Melvin Dresher, Albert William Tucker, Philip Wolfe. Contributions to the Theory of Games, Volume 3. Annals of Mathematics Studies. Princeton University Press. pp. 67–78. ISBN 978-0-691-07936-3. (Reprinted in Harold W. Kuhn, ed. Classics in Game Theory, Princeton University Press, 1997. ISBN 978-0-691-01192-9).

- Filar, J. & Vrieze, K. (1997). Competitive Markov Decision Processes. Springer-Verlag. ISBN 0-387-94805-8.

- Mertens, J. F. & Neyman, A. (1981). "Stochastic Games". International Journal of Game Theory 10 (2): 53–66. doi:10.1007/BF01769259.

- Neyman, A. & Sorin, S. (2003). "Stochastic Games and Applications". Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Press. ISBN 1-4020-1492-9.

- Shapley, L. S. (1953). "Stochastic games". PNAS 39 (10): 1095–1100. doi:10.1073/pnas.39.10.1095.

- Vieille, N. (2002). "Stochastic games: Recent results". Handbook of Game Theory. Amsterdam: Elsevier Science. pp. 1833–1850. ISBN 0-444-88098-4.

- Yoav Shoham; Kevin Leyton-Brown (2009). Multiagent systems: algorithmic, game-theoretic, and logical foundations. Cambridge University Press. pp. 153–156. ISBN 978-0-521-89943-7. (suitable for undergraduates; main results, no proofs)