Stiles–Crawford effect

The Stiles–Crawford effect (subdivided into the Stiles–Crawford effect of the first and second kind) is a property of the human eye that refers to the directional sensitivity of the cone photoreceptors.[1]

The Stiles–Crawford effect of the first kind is the phenomenon where light entering the eye near the edge of the pupil produces a lower photoreceptor response compared to light of equal intensity entering near the center of the pupil. The photoreceptor response is significantly lower than expected by the reduction in the photoreceptor acceptance angle of light entering near the edge of the pupil.[1] Measurements indicate that the peak photoreceptor sensitivity does not occur for light entering the eye directly through the center of the pupil, but at an offset of approximately 0.2-0.5 mm towards the nasal side.[2]

The Stiles–Crawford effect of the second kind is the phenomenon where the observed color of monochromatic light entering the eye near the edge of the pupil is different compared to that for the same wavelength light entering near the center of the pupil, regardless of the overall intensities of the two lights.[1]

Both of the Stiles–Crawford effects of the first and second kind are highly wavelength dependent, and they are most evident under photopic conditions.[1] There are several factors that contribute to the Stiles–Crawford effect, though it is generally accepted that it is primarily a result of the guiding properties of light of the cone photoreceptors. The reduced sensitivity to light passing near the edge of the pupil enhances human vision by reducing the sensitivity of the visual stimulus to light that exhibits significant optical aberrations and diffraction.[1]

Discovery

In the 1920s, Walter Stanley Stiles, a young physicist at the National Physical Laboratory in Teddington, England, examined the effects of street lighting and headlight features on automobile traffic accidents, which were becoming increasingly prevalent at the time. Stiles, along with his fellow National Physical Laboratory researcher Brian Hewson Crawford, set out to measure the effect of light intensity on pupil size. They constructed an apparatus where two independently controlled beams, both emitted by the same light source, entered the eye: a narrow beam through the center of the pupil, and a wider beam filling the whole pupil. The two beams alternated in time, and the subject was instructed to adjust the intensity of the wider beam until minimum flicker was observed, thus minimizing the difference in the visual stimulus between to the two beams. It was observed that the luminance of the pupil is not proportional to the pupil area. For instance, the luminance of a 30 mm2 pupil was found to be only twice that of a 10 mm2 pupil. In other words, to match the apparent brightness of light entering a 30 mm2 pupil, the luminance of light entering through a 10 mm2 pupil had to be increased by a factor of two, instead of the expected factor of three.[1]

Stiles and Crawford subsequently measured this effect more precisely by observing the visual stimulus of narrow beams of light selectively passed through various positions in the pupil using pinholes.[2] Using similar methods, the Stiles–Crawford effect has been verified by the scientific community.

Observations

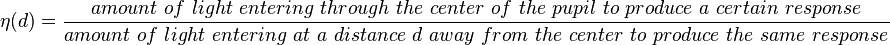

The Stiles Crawford Effect is quantified as a function of distance (d) away from the center of the pupil using the following equation:

where η is the relative luminance efficiency, and d is defined as positive on the temporal side of the pupil and negative on the nasal side of the pupil.[1]

Measurements of the relative luminance efficiency are typically largest and symmetric about some distance (dm), which is typically ranges from -0.2 to -0.5 mm, away from the center of the pupil towards the nasal side.[2] The significance of the Stiles–Crawford effect is evident by the fact that relative luminance efficiency drops by up to 90% for light entering near the edge of the pupil.[1]

Experimental data are fit accurately using the following empirical relationship:

where p(λ) is a wavelength dependent parameter which represents the magnitude of the Stiles–Crawford effect,[2] with larger values of p corresponding to a stronger falloff in the relative luminance efficiency as a function of distance from the center of the pupil. Measurements indicate that the value of p(λ) ranges from 0.05 to 0.08.

Explanation

Initially, it was thought that the Stiles–Crawford effect may be caused by the screening of light that passes near the edge of the pupil. This possibility was ruled out because variations in light extinction along different light paths through the pupil do not account for the significant reduction in the luminance efficiency. Furthermore, light screening does not explain the significant wavelength dependence of the Stiles–Crawford effect. Due to the large reduction in the Stiles–Crawford effect for rod vision tested under scotopic conditions [3] , scientists concluded that it must be dependent on properties of the retina; more specifically the photon capture properties of the cone photoreceptors.

Electromagnetic analysis of light rays incident on a model human cone revealed that the Stiles–Crawford effect is explained by the shape, size, and refractive indices of the various parts of cone photoreceptors,[4] which are roughly oriented towards the center of the pupil.[5] Since the width of human cone cells is on the order of two micrometers, which is on a similar order of magnitude as the wavelength of visible light, electromagnetic analysis indicated that the light capture phenomena in human cone cells are similar to those observed in optical waveguides.[4][6] More specifically, due the narrow confinement of light within cone protoreceptors, destructive or constructive interference of the electromagnetic field may occur within the cone photoreceptors for particular wavelengths of light, thus significantly affecting the overall absorption of light by the photopigment molecules.[7] This was the first analysis that sufficiently explained the non-monotonic wavelength dependence of p parameter that describes the strength the Stiles–Crawford effect.

However, due to simplicity of the cone models and the lack of accurate knowledge of the optical parameters of the human cone cell used in the electromagnetic analysis, it is unclear whether other factors such as the photopigment concentrations [8] may contribute to the Stiles–Crawford effect. Due to the complexity of a single cone photoreceptor and the layers of the retina which lie ahead of the cone photoreceptor on the light path, as well as the randomness associated with the distribution and orientation of cone photoreceptors, it is extremely difficult to fully model all of the factors which may affect the production of the visual stimulus in an eye.[1]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 Gerald Westheimer (2008), "Directional sensitivity of the retina: 75 year of Stiles-Crawford effect," Proc. R. Soc. B 275: 2777-2786.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Walter Stanley Stiles and Brian Hewson Crawford (1933), "The luminous efficiency of rays entering the eye pupil at different points," Proc. R. Soc. Lond B 112: 428-450.

- ↑ Francoise Flamant, Walter Stanley Stiles Westheimer (1948), "The Directional and Spectral Sensitivities of the Retinal Rods to Adapting Fields of Different Wavelengths," J. Physiol. 107: 187-202.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Alan W. Snyder and Colin Pask (1973), "The Stiles-Crawford effect - explanation and consequences," Vis. Res. 13: 1115-1137.

- ↑ Alan M. Laties and Jay M. Enoch (1971), "An Analysis of Retinal Receptor Orientation I. Angular Relationship of Neighboring Photoreceptors," Inv. Opht. Vis. Sci. 10: 69-77.

- ↑ G. Toraldo di Francia (1948), "Retinal Cones as Dielectric Antennas," J. Opt. Soc. Am. 39: 324.

- ↑ Jay M. Enoch (1963), "Optical properties of the retinal receptors," J. Opt. Soc. Am. 53: 71-85.

- ↑ P. L. Walraven and M. A. Bouman (1960), "," J. Opt. Soc. Am. 50: 780-784.