Sthenurus

| Sthenurus[1][2] Temporal range: Pleistocene | |

|---|---|

| |

| S. stirlingi | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Infraclass: | Marsupialia |

| Order: | Diprotodontia |

| Family: | Macropodidae |

| Subfamily: | Sthenurinae |

| Genus: | †Sthenurus (Owen, 1873a) |

| Paleospecies | |

| |

Sthenurus ("strong tail") is an extinct genus of kangaroo. With a length of about 3 m (10 ft), some species were twice as large as modern extant species. Sthenurus was related to the better-known Procoptodon. The subfamily Sthenurinae is believed to have separated from its sister taxon, the Macropodinae (kangaroos and wallabies), halfway through the Miocene and then its population grew during the Pliocene.[3]

Fossil habitats

Research by Darren R. Gröcke from Monash University, analysed the diets of fauna at various fossil site localites in South Australia, using stable carbon isotope analysis 13C/12C of collagen. He found that at older localities like Cooper Creek the species of Sthenurus were adapted to a diet of leaves and twigs (browsing). This was due to the wet climate of the time period between 132,000-108,000 years (TL and uranium dating), which allowed for a more varied vegetation cover.

At the Baldina Creek fossil site 30,000 years (C14 dating), the genus had transitioned to a diet of grass-grazing. During this time, the area was open grasslands with sparse tree cover as the continent was drier than today. But at Dempsey's Lake (36-25,000 years) and Rockey River (19,000 C14 dating), their diet was of both grazing and browsing. This analysis may be because of a wetter climatic period. The overall anatomy of the genus did not alter in response to the change in diet and dentition did not adapt to the varying toughness of the vegetation between grasses, shrubs and trees.[4]

Other animals found in the Cuddie Springs habitat include the flightless bird Genyornis, the red kangaroo, Diprotodon, humans and many others.[5][6]

Examination skeletal remains of Sthenurus from Lake Callabonna, northern South Australia revealed that as the animals were trapped as they floundered in the clay mud while attempting to cross the floor of the lake during tow-water or dry times. The data shows that three closely allied sthenurine species coexisted sympatrically at Lake Callabonna: a new giant taxon, S. stirlingi, an intermediate-sized S. tindalei, and the considerably smaller S. andersoni. Comparative osteology of these Sthenurus species with Macropus giganteus emphasizes how different sthenurine kangaroos were from extant kangaroos, especially with the sthenurines' short, deep skulls, long front feet with very reduced lateral digits, and the monodactyl hind feet.[7]

Teapot Creek, a tributary of the MacLaughlin River in the Southern Monaro, southeastern New South Wales contains a sequence of terraces. The highest and oldest of these terraces was reported to contain the remains of fossil mammals found in Plio-Pleistocene fossil deposits elsewhere in Eastern Australia. Sthenurus atlas, S. occidentalis, and S. newtonae are some of the species identified from the fossils found in the terrace.[8]

Paleodiet

Examining the structure and lifestyle of this specific species is difficult due to the fact that not much has surfaced in regards to them. However, even within the rarity of discoveries relating to the kangaroo-like species, scientists were able to use their findings in order to learn more about their lifestyles. For example, scientists broke down the few bones that they had discover during the process of isotope analysis (which is the study of the distribution of certain isotopes that ease the process of drawing conclusions when determining food chains) and retrieved material which allowed them to draw the conclusion regarding their paleodiet. These animals were herbivores because the material they retrieved drew back to the plantation that was Australia (where their bones were found) had.[9]

Anatomy

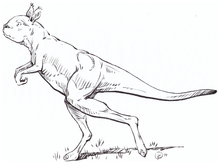

In anatomy they had a tail shorter but stronger than present species of kangaroo, and only one toe instead of three like the red kangaroo. At the end of the foot was a small hoof like nail suited for flat terrain;[10] this toe is considered their fourth toe.[11]

Their skeletal structure was very robust with powerful hind limbs, broad pelvis, longer arms and phalanges than modern species and a short neck. Their phalangel bones that make up their fingers may have been used to hold stems and twigs. These unique adaptations suited their feeding habits of browsing in the case of S. occidentalis, but other species were most likely grazers.[10]

The estimated body mass of the largest species is thought to be two hundred and forty kilograms which is nearly three times the size of extant species. Due to the giant height and heavy weight of the biggest species, it is possible that this species did not hop as a form of locomotion but performed a bipedal for of walking similar to humans. This gait would be done at slow speeds since hopping at slow speeds would be a waste of energy. Pentapedal movement or bipedal hopping no longer seems to be an option for these massive kangaroos.[12]

There was a morphological difference between the scapulae (or shoulder blade) of the Sthenurine and the extant as well as the extinct macropodids.[13]

They possessed a short deep skull which was suited for eyes with stereoscopic vision; this allowed for better vision.[11]

Unlike modern kangaroos, which are plantigrade hoppers, Sthenurus was an unguligrade biped, walking in a similar fashion to hominids.[14]

Skull

Paleospecies S. stirlingi had a large, dolichocephalic skull with a more elevated braincase position and an inflamed nasal frontal region in comparison to the contemperaneous skull of the S. tindelai.[15] S. andersoni skull fossils show a dome-like forehead that is unique to S. andersoni among other otherdolichocephalic sthenurines. This is attributed to the continuous high vaulting of the frontals above the orbits and the line of the rostrum.

Teeth

These structures were tough and strongly enameled, useful for tough vegetation and with a striation pattern.[10]

In paleospecies S. stirlingi fossil evidence shows that tooth row curves medially (anteriorly and posteriorly) from a line tangential to the labial side of the molars at the anterior ridge of the masseteric processes.[15]

The fossils of teeth may also suggest that the sthenurines and macropodines shared a common ancestor. They share many synapomorphic character states. They each have well developed lophs on molars and both lack a posthypocristid.[16]

Human interaction

From evidence gathered at Cuddie Springs according to Judith Field and Richard Fullagerit (as cited in Macey 2003) it is known that Native Australians inhabited the same habitat as that of Sthenurus and various other extant and extinct species of animal. At this locality there seems to be a lack of any specific tools suitable for hunting. Instead there are tools used to cut meat off the bone, as there is blood residue left on the stone tools. Any material made of wood for hunting like the boomerang and spear has either not survived intact or was not used by the people of the time in this locality.[5][6] While this evidence may suggest that human contact with the Sthenurus and all Australian megafauna could have caused the extinction of these mammals, some studies show the extinction was probably under way before human contact. The Sthenurus were herbivores and when a great climate change began to occur they did not change their eating habits. This probably had a much larger impact on the extinction of this particular genus.[17]

References

- ↑ Haaramo, M. (2004-12-20). "Mikko's Phylogeny Archive: Macropodidae - kenguroos". Retrieved 2007-03-15.

- ↑ Gavin J. Prideaux, John A. Long, Linda K. Ayliffe, John C. Hellstrom, Brad Pillans, Walter E. Boles, Mark N. Hutchinson, Richard G. Roberts, Matthew L. Cupper, Lee J. Arnold, Paul D. Devine & Natalie M. Warburton (2007-01-25). "An arid-adapted middle Pleistocene vertebrate fauna from south-central Australia". Nature 445 (7126): 422–425. doi:10.1038/nature05471. PMID 17251978.

- ↑ Sears, K. E. (2005), Role of development in the evolution of the scapula of the giant sthenurine kangaroos (Macropodidae: Sthenurinae). J. Morphol., 265: 226–236. doi: 10.1002/jmor.10353

- ↑ Darren R. Gröcke (N/A) VIEPS Department of Earth Sciences, Monash University, Clayton, VIC 3168, Australia ST-grock@artemis.earth.monash.edu.au Carbon-Isotope Shifts Recorded in Megafaunal Dietary Niches of C3 and C4 Plants in the Late Pleistocene of South Australia: Correlation with Palaeofloral Reconstructions. Monash University, Clayton. Retrieved on 2007-06-26.

- 1 2 Macey, Richard (October 2003). "Maybe they didn't fit in the oven". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 2007-09-24.

- 1 2 Furby, Judith (December 1996). "Dinnertime at Cuddie Springs: hunting and butchering megafauna?". University of Sydney. Archived from the original on 2007-09-11. Retrieved 2007-09-24.

- ↑ WELLS, RT; TEDFORD, RH BULLETIN OF THE AMERICAN MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY Issue: 225 Pages: 1-111 Published: 1995

- ↑ Armand, L (Armand, L); Ride, WDL (Ride, WDL); Taylor, G (Taylor, G) PROCEEDINGS OF THE LINNEAN SOCIETY OF NEW SOUTH WALES Volume: 122 Pages: 101-121 Published: DEC 22 2000

- ↑ By: Grocke, DR AUSTRALIAN JOURNAL OF BOTANY Volume: 45 Issue: 3 Pages: 607-617 Published: 1997

- 1 2 3 "Extinct Animals- Simosthenurus occidentalis". ParksWeb. 2006. Archived from the original on 2007-09-05. Retrieved 2007-07-02.

- 1 2 "The age of the Megafauna". ABC online. 2007. Retrieved 2007-07-02.

- ↑ Janis CM, Buttrill K, Figueirido B (2014) Locomotion in Extinct Giant Kangaroos: Were Sthenurines Hop-Less Monsters? PLoS ONE 9(10): e109888. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0109888

- ↑ Karen E. Sears*Division of Developmental Biology, Department of Pediatrics, University of Colorado Health Sciences Center,Aurora, Colorado 80045

- ↑ Janis, CM; Buttrill, K; Figueirido, B (2014). "Locomotion in Extinct Giant Kangaroos: Were Sthenurines Hop-Less Monsters?". PLoS ONE 9 (10). doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0109888. Retrieved October 15, 2014.

- 1 2 Wells, Roderick Tucker (1995). "Sthenurus (Macropodidae, Marsupialia) from the Pleistocene of Lake Callabonna, South-Australia". Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History (225): 23.

- ↑ Flannery, T.F. (May 1983). Revision in the macropodid subfamily Sthenurinae (Marsupialia: Macropodoidea) and the relationships of the species of Troposodon and Lagostrophus. Aust. Mammal 6: 15-28. Retrieved 2014-10-22.

- ↑ Wroe, Stephen; Field, Judith (November 2006). A review of the evidence for a human role in the extinction of Australian megafauna and an alternative interpretation. Retrieved 2014-10-22.

- Gavin Prideaux, "Systematics and Evolution of the Sthenurine Kangaroos" (April 1, 2004). UC Publications in Geological Sciences. Paper vol_146. http://repositories.cdlib.org/ucpress/ucpgs/vol_146

External links

| Wikispecies has information related to: Sthenurus |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sthenurus. |

- Victoria museum.

- Australias Vanished Beasts, With a picture of Sthenurus.

- Sthenurus from the American Museum of Natural History.

- Outlines of the various species.

- Naracoorte caves.