Stevens–Johnson syndrome

| Stevens–Johnson syndrome | |

|---|---|

Man with Stevens–Johnson syndrome | |

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | Dermatology |

| ICD-10 | L51.1 |

| ICD-9-CM | 695.13 |

| OMIM | 608579 |

| DiseasesDB | 4450 |

| MedlinePlus | 000851 |

| eMedicine | emerg/555 derm/405 |

| Patient UK | Stevens–Johnson syndrome |

| MeSH | D013262 |

| Orphanet | 36426 |

Stevens–Johnson syndrome, a form of toxic epidermal necrolysis, is a life-threatening skin condition, in which cell death causes the epidermis to separate from the dermis. The syndrome is thought to be a hypersensitivity complex that affects the skin and the mucous membranes. The most well-known causes are certain medications (such as lamotrigine), but it can also be due to infections, or more rarely, cancers.[1]

Classification

Stevens–Johnson syndrome (SJS) is a milder form of toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN).[2] These conditions were first recognised in 1922.[3] A classification first published in 1993, that has been adopted as a consensus definition, identifies Stevens–Johnson syndrome, toxic epidermal necrolysis, and SJS/TEN overlap. All three are part of a spectrum of severe cutaneous reactions (SCAR) which affect skin and mucous membranes.[4] The distinction between SJS, SJS/TEN overlap, and TEN is based on the type of lesions and the amount of the body surface area with blisters and erosions.[4] Blisters and erosions cover between 3% and 10% of the body in SJS, 11–30% in SJS/TEN overlap, and over 30% in TEN.[4] The skin pattern most commonly associated with SJS is widespread, often joined or touching (confluent), papuric spots (macules) or flat small blisters or large blisters which may also join together.[4] These occur primarily on the torso.[4]

SJS, TEN, and SJS/TEN overlap can be mistaken for erythema multiforme.[5] Erythema multiforme, which is also within the SCAR spectrum, differs in clinical pattern and etiology.[4] Although both SJS and TEN can also be caused by infections, they are most often adverse effects of medications.[4]

Signs and symptoms

SJS usually begins with fever, sore throat, and fatigue, which is commonly misdiagnosed and therefore treated with antibiotics. Ulcers and other lesions begin to appear in the mucous membranes, almost always in the mouth and lips, but also in the genital and anal regions. Those in the mouth are usually extremely painful and reduce the patient's ability to eat or drink. Conjunctivitis of the eyes occurs in about 30% of children who develop SJS. A rash of round lesions about an inch across arises on the face, trunk, arms and legs, and soles of the feet, but usually not the scalp.[6]

Causes

SJS is thought to arise from a disorder of the immune system.[6] The immune reaction can be triggered by drugs or infections.[7] Genetic factors are associated with a predisposition to SJS.[8] The cause of SJS is unknown in one-quarter to one-half of cases.[8]

Medication

Although SJS can be caused by viral infections and malignancies, the main cause is medications.[4] A leading cause appears to be the use of antibiotics, particularly sulfa drugs.[8][9] Between 100 and 200 different drugs may be associated with SJS.[10] No reliable test exists to establish a link between a particular drug and SJS for an individual case.[4] Determining what drug is the cause is based on the time interval between first use of the drug and the beginning of the skin reaction. A published algorithm (ALDEN) to assess drug causality gives structured assistance in identifying the responsible medication.[4][11]

SJS may be caused by adverse effects of the drugs vancomycin, allopurinol, valproate, levofloxacin, diclofenac, etravirine, isotretinoin, fluconazole,[12] valdecoxib, sitagliptin, oseltamivir, penicillins, barbiturates, sulfonamides, phenytoin, azithromycin, oxcarbazepine, zonisamide, modafinil,[13] lamotrigine, nevirapine, pyrimethamine, ibuprofen,[14] ethosuximide, carbamazepine, bupropion, telaprevir,[15][16] and nystatin.[17][18]

Medications that have traditionally been known to lead to SJS, erythema multiforme, and toxic epidermal necrolysis include sulfonamide antibiotics, penicillin antibiotics, cefixime (antibiotic), barbiturates (sedatives), lamotrigine, phenytoin (e.g., Dilantin) (anticonvulsants) and trimethoprim. Combining lamotrigine with sodium valproate increases the risk of SJS.[19]

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are a rare cause of SJS in adults; the risk is higher for older patients, women, and those initiating treatment.[3] Typically, the symptoms of drug-induced SJS arise within a week of starting the medication. Similar to NSAIDs, paracetamol (acetaminophen) has also caused rare cases[20][21] of SJS. People with systemic lupus erythematosus or HIV infections are more susceptible to drug-induced SJS.[6]

Infections

The second most common cause of SJS and TEN is infection, particularly in children. This includes upper respiratory infections, otitis media, pharyngitis, and Epstein-Barr virus, Mycoplasma pneumoniae and cytomegalovirus infections. The routine use of medicines such as antibiotics, antipyretics and analgesics to manage infections can make it difficult to identify if cases were caused by the infection or medicines taken.[22]

Viral diseases reported to cause SJS include: herpes simplex virus (debated), AIDS, coxsackievirus, influenza, hepatitis, and mumps.[8]

In pediatric cases, Epstein-Barr virus and enteroviruses have been associated with SJS.[8]

Recent upper respiratory tract infections have been reported by more than half of patients with SJS.[8]

Bacterial infections linked to SJS include group A beta-hemolytic streptococci, diphtheria, brucellosis, lymphogranuloma venereum, mycobacteria, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, rickettsial infections, tularemia, and typhoid.[8]

Fungal infections with coccidioidomycosis, dermatophytosis, and histoplasmosis are also considered possible causes.[8] Malaria and trichomoniasis, protozoal infections, have also been reported as causes.[8]

Genetics

In some East Asian populations studied (Han Chinese and Thai), carbamazepine- and phenytoin-induced SJS is strongly associated with HLA-B*1502 (HLA-B75), an HLA-B serotype of the broader serotype HLA-B15.[23][24][25] A study in Europe suggested the gene marker is only relevant for East Asians.[26][27]

Based on the Asian findings, similar studies in Europe showed 61% of allopurinol-induced SJS/TEN patients carried the HLA-B58 (phenotype frequency of the B*5801 allele in Europeans is typically 3%). One study concluded: "Even when HLA-B alleles behave as strong risk factors, as for allopurinol, they are neither sufficient nor necessary to explain the disease."[28]

Pathology

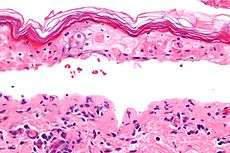

SJS, like TEN and erythema multiforme, is characterized by confluent epidermal necrosis with minimal associated inflammation. The acuity is apparent from the (normal) basket weave-like pattern of the stratum corneum. An idiosyncratic, delayed-hypersensitivity reaction has been implicated in the pathophysiology of SJS. Certain population groups appear more susceptible to develop SJS than the general population. Slow acetylators, patients who are immunocompromised (especially those infected with HIV), and patients with brain tumors undergoing radiotherapy with concomitant antiepileptics are among those at most risk.

Slow acetylators are people whose liver cannot completely detoxify reactive drug metabolites. For example, patients with sulfonamide-induced toxic epidermal necrolysis have been shown to have a slow acetylator genotype that results in increased production of sulfonamide hydroxylamine via the cytochrome P-450 pathway. These drug metabolites may have direct toxic effects or may act as haptens that interact with host tissues, rendering them antigenic.

Antigen presentation and production of tumor necrosis factor (TNF)–alpha by the local tissue dendrocytes results in the recruitment and augmentation of T-lymphocyte proliferation and enhances the cytotoxicity of the other immune effector cells. A "killer effector molecule" has been identified that may play a role in the activation of cytotoxic lymphocytes. The activated CD8+ cytotoxic T cells, in turn, can induce epidermal cell apoptosis via several mechanisms, which include the release of granzyme B and perforin.

Perforin, a pore-making monomeric granule released from natural killer cells and cytotoxic T lymphocytes, kills target cells by forming polymers and tubular structures not unlike the membrane attack complex of the complement system. Apoptosis of keratinocytes can also take place as a result of ligation of their surface death receptors with the appropriate molecules. Those can trigger the activation of the caspase system, leading to DNA disorganization and cell death.

Apoptosis of keratinocytes can be mediated by direct interaction between the cell-death receptor Fas and its ligand. Both can be present on the surfaces of the keratinocytes. Alternatively, activated T-cells can release soluble Fas ligand and interferon-gamma, which induces Fas expression by keratinocytes. Researchers have found increased levels of soluble Fas ligand in the sera of patients with SJS/TEN before skin detachment or onset of mucosal lesions.

The death of keratinocytes causes separation of the epidermis from the dermis. Once apoptosis ensues, the dying cells provoke recruitment of more chemokines. This can perpetuate the inflammatory process, which leads to extensive epidermal necrolysis. Higher doses and rapid introduction of allopurinol and lamotrigine may also increase the risk of developing SJS/TEN. Risk is lessened by starting these at the low doses and titrating gradually. Some evidence indicates systemic lupus is a risk factor, as well.

Treatment

SJS constitutes a dermatological emergency. Patients with documented Mycoplasma infections can be treated with oral macrolide or oral doxycycline.[6]

Initially, treatment is similar to that for patients with thermal burns, and continued care can only be supportive (e.g. intravenous fluids and nasogastric or parenteral feeding) and symptomatic (e.g., analgesic mouth rinse for mouth ulcer). Dermatologists and surgeons tend to disagree about whether the skin should be debrided.[6]

Beyond this kind of supportive care, no treatment for SJS is accepted. Treatment with corticosteroids is controversial. Early retrospective studies suggested corticosteroids increased hospital stays and complication rates. No randomized trials of corticosteroids were conducted for SJS, and it can be managed successfully without them.[6]

Other agents have been used, including cyclophosphamide and cyclosporin, but none has exhibited much therapeutic success. Intravenous immunoglobulin treatment has shown some promise in reducing the length of the reaction and improving symptoms. Other common supportive measures include the use of topical pain anaesthetics and antiseptics, maintaining a warm environment, and intravenous analgesics.

An ophthalmologist should be consulted immediately, as SJS frequently causes the formation of scar tissue inside the eyelids, leading to corneal vascularization, impaired vision, and a host of other ocular problems. Those with chronic ocular surface disease caused by SJS may find some improvement with PROSE treatment (prosthetic replacement of the ocular surface ecosystem treatment).[29]

Prognosis

SJS (with less than 10% of body surface area involved) has a mortality rate of around 5%. The mortality for toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) is 30–40%. The risk for death can be estimated using the SCORTEN scale, which takes a number of prognostic indicators into account.[30] Other outcomes include organ damage/failure, cornea scratching, and blindness.

Epidemiology

SJS is a rare condition, with a reported incidence of around 2.6[6] to 6.1[3] cases per million people per year. In the United States, about 300 new diagnoses are made each year. The condition is more common in adults than in children. Women are affected more often than men, with cases occurring at a two to one ratio.[3]

History

SJS is named for Albert Mason Stevens and Frank Chambliss Johnson, American pediatricians who jointly published a description of the disorder in the American Journal of Diseases of Children in 1922.[31][32]

Notable cases

- Ab-Soul, American hip hop recording artist and member of Black Hippy[33]

- Padma Lakshmi, actress, model, television personality, and cookbook writer[34]

- Manute Bol, former NBA player. Bol died from complications of Stevens–Johnson syndrome as well as kidney failure.[35]

- Gene Sauers, three-time PGA Tour winner[36]

- Samantha Reckis, a seven-year-old Plymouth, Massachusetts girl who lost the skin covering 95% of her body after taking children's Motrin in 2003. In 2013, a jury awarded her $63M in a lawsuit against Johnson & Johnson, one of the largest lawsuits of its kind.[37] The decision was upheld in 2015.[38]

See also

References

- ↑ http://www.genome.gov/27560487

- ↑ Rehmus, W. E. (November 2013). "Stevens–Johnson Syndrome (SJS) and Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis (TEN)". In Porter, R. S. The Merck Manual ((online version) 19th ed.). Whitehouse Station, NJ: Merck & Co.

- 1 2 3 4 Ward KE, Archambault R, Mersfelder TL; Archambault; Mersfelder (2010). "Severe adverse skin reactions to nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs: A review of the literature". American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy 67 (3): 206–213. doi:10.2146/ajhp080603. PMID 20101062.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Mockenhaupt M (2011). "The current understanding of Stevens–Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis". Expert Review of Clinical Immunology 7 (6): 803–15. doi:10.1586/eci.11.66. PMID 22014021.

- ↑ Auquier-Dunant A, Mockenhaupt M, Naldi L, Correia O, Schröder W, Roujeau JC; Mockenhaupt; Naldi; Correia; Schröder; Roujeau; SCAR Study Group. Severe Cutaneous Adverse Reactions (2002). "Correlations between clinical patterns and causes of Erythema Multiforme Majus, Stevens-Johnson Syndrome, and Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis results of an international prospective study". Archives of Dermatology 138 (8): 1019–24. doi:10.1001/archderm.138.8.1019. PMID 12164739.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Tigchelaar, H.; Kannikeswaran, N.; Kamat, D. (December 2008). "Stevens–Johnson Syndrome: An intriguing diagnosis". pediatricsconsultantlive.com. UBM Medica. (registration required (help)).

- ↑ Tan SK, Tay YK; Tay (2012). "Profile and pattern of Stevens-Johnson Syndrome and Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis in a general hospital in Singapore: Treatment outcomes". Acta Dermato-Venereologica 92 (1): 62–6. doi:10.2340/00015555-1169. PMID 21710108.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Foster, C. Stephen; Ba-Abbad, Rola; Letko, Erik; Parrillo, Steven J.; et al. (12 August 2013). "Stevens-Johnson Syndrome". Medscape Reference. Roy, Sr., Hampton (article editor). Etiology.

- ↑ Teraki Y, Shibuya M, Izaki S; Shibuya; Izaki (2010). "Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis due to anticonvulsants share certain clinical and laboratory features with drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome, despite differences in cutaneous presentations". Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 35 (7): 723–8. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2230.2009.03718.x. PMID 19874350.

- ↑ Cooper KL (2012). "Drug reaction, skin care, skin loss". Crit Care Nurse 32 (4): 52–9. doi:10.4037/ccn2012340. PMID 22855079.

- ↑ Sassolas B, Haddad C, Mockenhaupt M, Dunant A, Liss Y, Bork K, Haustein UF, Vieluf D, Roujeau JC, Le Louet H; Haddad; Mockenhaupt; Dunant; Liss; Bork; Haustein; Vieluf; Roujeau; Le Louet (2010). "ALDEN, an algorithm for assessment of drug causality in Stevens-Johnson Syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis: Comparison with case-control analysis". Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics 88 (1): 60–8. doi:10.1038/clpt.2009.252. PMID 20375998.

- ↑ "Diflucan One" (data sheet). Medsafe; New Zealand Ministry of Health. 29 April 2008. Archived from the original on 2010-06-03.

- ↑ "Provigil (modafinil) Tablets". MedWatch. US Food and Drug Administration. 24 October 2007.

- ↑ Raksha MP, Marfatia YS; Marfatia (2008). "Clinical study of cutaneous drug eruptions in 200 patients". Indian Journal of Dermatology, Venereology and Leprology 74 (1): 80. doi:10.4103/0378-6323.38431. PMID 18193504.

- ↑ "Incivek prescribing information" (PDF) (package insert). Vertex Pharmaceuticals. December 2012.

- ↑ Surovik J, Riddel C, Chon SY; Riddel; Chon (2010). "A case of bupropion-induced Stevens-Johnson syndrome with acute psoriatic exacerbation". Journal of Drugs in Dermatology: JDD 9 (8): 1010–2. PMID 20684153.

- ↑ Fagot JP, Mockenhaupt M, Bouwes-Bavinck JN, Naldi L, Viboud C, Roujeau JC; Mockenhaupt; Bouwes-Bavinck; Naldi; Viboud; Roujeau; Euroscar Study (2001). "Nevirapine and the risk of Stevens–Johnson syndrome or toxic epidermal necrolysis". AIDS 15 (14): 1843–8. doi:10.1097/00002030-200109280-00014. PMID 11579247.

- ↑ Devi K, George S, Criton S, Suja V, Sridevi PK; George; Criton; Suja; Sridevi (2005). "Carbamazepine – The commonest cause of toxic epidermal necrolysis and Stevens–Johnson syndrome: A study of 7 years". Indian Journal of Dermatology, Venereology and Leprology 71 (5): 325–8. doi:10.4103/0378-6323.16782. PMID 16394456.

- ↑ http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17428116

- ↑ Khawaja A, Shahab A, Hussain SA; Shahab; Hussain (2012). "Acetaminophen induced Steven Johnson syndrome-Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis overlap". Journal of Pakistan Medical Association 62 (5): 524–7. PMID 22755330.

- ↑ Trujillo C, Gago C, Ramos S; Gago; Ramos (2010). "Stevens-Jonhson syndrome after acetaminophen ingestion, confirmed by challenge test in an eleven-year-old patient". Allergol Immunopathol (Madr) 38 (2): 99–100. doi:10.1016/j.aller.2009.06.009. PMID 19875224.

- ↑ Bentley, John; Sie, David (8 October 2014). "Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis". The Pharmaceutical Journal 293 (7832). Retrieved 8 October 2014.

- ↑ Chung WH, Hung SI, Hong HS, Hsih MS, Yang LC, Ho HC, Wu JY, Chen YT; Hung; Hong; Hsih; Yang; Ho; Wu; Chen (2004). "Medical genetics: A marker for Stevens–Johnson syndrome". Brief Communications. Nature v428 (v6982): v486. doi:10.1038/428486a. PMID 15057820.

- ↑ Locharernkul C, Loplumlert J, Limotai C, Korkij W, Desudchit T, Tongkobpetch S, Kangwanshiratada O, Hirankarn N, Suphapeetiporn K, Shotelersuk V; Loplumlert; Limotai; Korkij; Desudchit; Tongkobpetch; Kangwanshiratada; Hirankarn; Suphapeetiporn; Shotelersuk (2008). "Carbamazepine and phenytoin induced Stevens–Johnson syndrome is associated with HLA-B*1502 allele in Thai population". Epilepsia 49 (12): 2087–91. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1167.2008.01719.x. PMID 18637831.

- ↑ Man CB, Kwan P, Baum L, Yu E, Lau KM, Cheng AS, Ng MH; Kwan; Baum; Yu; Lau; Cheng; Ng (2007). "Association between HLA-B*1502 allele and antiepileptic drug-induced cutaneous reactions in Han Chinese". Epilepsia 48 (5): 1015–8. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1167.2007.01022.x. PMID 17509004.

- ↑ Alfirevic A, Jorgensen AL, Williamson PR, Chadwick DW, Park BK, Pirmohamed M; Jorgensen; Williamson; Chadwick; Park; Pirmohamed (2006). "HLA-B locus in Caucasian patients with carbamazepine hypersensitivity". Pharmacogenomics 7 (6): 813–8. doi:10.2217/14622416.7.6.813. PMID 16981842.

- ↑ Lonjou C, Thomas L, Borot N, Ledger N, de Toma C, LeLouet H, Graf E, Schumacher M, Hovnanian A, Mockenhaupt M, Roujeau JC; Thomas; Borot; Ledger; De Toma; Lelouet; Graf; Schumacher; Hovnanian; Mockenhaupt; Roujeau; Regiscar (2006). "A marker for Stevens–Johnson syndrome ...: Ethnicity matters" (PDF). The Pharmacogenomics Journal 6 (4): 265–8. doi:10.1038/sj.tpj.6500356. PMID 16415921.

- ↑ Lonjou C, Borot N, Sekula P, Ledger N, Thomas L, Halevy S, Naldi L, Bouwes-Bavinck JN, Sidoroff A, de Toma C, Schumacher M, Roujeau JC, Hovnanian A, Mockenhaupt M; Borot; Sekula; Ledger; Thomas; Halevy; Naldi; Bouwes-Bavinck; Sidoroff; De Toma; Schumacher; Roujeau; Hovnanian; Mockenhaupt; Regiscar Study (2008). "A European study of HLA-B in Stevens–Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis related to five high-risk drugs". Pharmacogenetics and Genomics 18 (2): 99–107. doi:10.1097/FPC.0b013e3282f3ef9c. PMID 18192896.

- ↑ Ciralsky, JB; Sippel, KC; Gregory, DG (July 2013). "Current ophthalmologic treatment strategies for acute and chronic Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis.". Current opinion in ophthalmology 24 (4): 321–8. doi:10.1097/icu.0b013e3283622718. PMID 23680755.

- ↑ Foster et al. 2013, Prognosis.

- ↑ Enerson, Ole Daniel (ed.), "Stevens-Johnson syndrome", Whonamedit?.

- ↑ Stevens, A.M.; Johnson, F.C. (1922). "A new eruptive fever associated with stomatitis and ophthalmia; Report of two cases in children". American Journal of Diseases of Children 24 (6): 526–33. doi:10.1001/archpedi.1922.04120120077005.

- ↑ Ramirez, Erika (8 August 2012). "Ab-Soul's timeline: The rapper's life from 5 years old to now". billboard.com. Billboard. Retrieved 2012-12-07.

- ↑ Cartner-Morley, Jess (8 April 2006). "Beautiful and Damned". The Guardian.

- ↑ "Manute Bol dies at age 47". FanHouse. AOL. 19 June 2010. Archived from the original on 2010-06-21.

- ↑ Graff, Chad (31 July 2013). "3M golf: Gene Sauers thriving after torturous battle with skin disease". St. Paul Pioneer Press.

- ↑ "Family awarded $63 million in Motrin case". Boston Globe. 2013-02-13.

- ↑ "$63 million verdict in Children’s Motrin case upheld". Boston Globe. 2015-04-17.

Further reading

- Boyer, Woodrow Allen (May 2008). Understanding Stevens–Johnson Syndrome & Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis (New Expanded ed.). Raleigh, North Carolina: Lulu Press.

- Bentley, John; Sie, David (2014-10-08). "Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis". The Pharmaceutical Journal 293 (7832). Retrieved 2014-10-08.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||