Steven Stayner

| Steven Stayner | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

Steven Gregory Stayner April 18, 1965 Merced, California, U.S. |

| Disappeared |

December 4, 1972 (aged 7) Merced, California, U.S. |

| Status | Found |

| Died |

September 17, 1989 (aged 24) Merced, California, U.S. |

| Cause of death | Road accident |

| Resting place | Merced Cemetery District |

| Nationality | American |

| Spouse(s) | Jody Edmondson (m. 1985–89) |

| Children | 2 |

| Relatives | Cary Stayner (brother) |

Steven Gregory Stayner (April 18, 1965 – September 17, 1989) was an American kidnap victim. Stayner was abducted from the Central California city and county of Merced, California at the age of seven and held until he was 14, when he escaped and rescued another victim, Timothy White, in 1980. Stayner died in 1989 in a motorcycle accident while driving home from work.

Birth and family

Stayner was the third of five children born to Delbert and Kay Stayner in Merced, California.[1] He had three sisters and an older brother, Cary.[2] In 2002, Cary was convicted and sentenced to death for the 1999 murder of four women.[3]

Kidnapping

On the afternoon of December 4, 1972, Stayner was approached on his way home from school by a man named Ervin Edward Murphy, an acquaintance of Kenneth Parnell.[4] Murphy, described by those who knew him as a trusting, naïve, and simple-minded man,[4] had been enlisted by convicted child rapist Parnell (who had passed himself off as an aspiring minister to Murphy)[5][6] into helping him abduct a young boy so that Parnell could "raise him in a religious-type deal," as Murphy later stated.[6]

Acting on instructions from Parnell, Murphy passed out gospel tracts to boys walking home from school that day[6][7] and, after spotting Stayner, claimed to be a church representative seeking donations. Stayner later claimed that Murphy asked him if his mother would be willing to donate any items to the church; when the boy replied that she would, Murphy then asked Stayner where he lived and if he would be willing to take Murphy to his home. After Stayner agreed, a white Buick driven by Parnell pulled up, and Stayner willingly climbed into the car with Murphy. Parnell then drove a confused Stayner to his cabin in nearby Catheys Valley instead.[7] (Unbeknownst to Stayner, Parnell's cabin was located only several hundred feet from his maternal grandfather's residence.)[8] Parnell molested Stayner for the first time early the following morning.[9]

After telling Parnell that he wanted to go home many times during his first week with the man, Parnell told Stayner that he had been granted legal custody of the boy because his parents could not afford so many children and that they did not want him anymore.[10]

Parnell began calling the boy Dennis Gregory Parnell,[11] retaining Stayner's real middle name and his real birth date when enrolling him in various schools over the next several years. Parnell passed himself off as Stayner's father, and the two moved frequently around California, among others living in Santa Rosa and Comptche. He allowed Stayner to begin drinking at a young age and to come and go virtually as he pleased.[4] One of the few positive aspects of Stayner's life with Parnell was the dog he had received as a gift from Parnell, a Manchester Terrier that he named Queenie. This dog had been given to Parnell by his mother, who was not aware of Stayner's existence during the period when he was living with Parnell.[12]

For a period of over a year, a woman named Barbara Mathias, along with one or more of her children, lived with Parnell and Stayner. She later claimed to have been completely unaware that "Dennis" had, in fact, been kidnapped.[13]

Escape

As Stayner entered puberty, Parnell began to look for a younger child to kidnap. On February 14, 1980, Parnell and a teenage friend of Stayner's named Randall Sean Poorman kidnapped five-year-old Timothy White in Ukiah, California. Motivated in part by the young boy's distress, Stayner decided to escape with him, intending to return the boy to his parents and then escape himself. On March 1, 1980, while Parnell was away at his night security job, Stayner left with White and hitchhiked into Ukiah. Unable to locate White's home address, he decided to have White walk into the police department to ask for help, before escaping himself. Before he could successfully escape, the police spotted the two boys and took them into custody. Stayner immediately identified Timmy White and then revealed his own true identity and story.[14]

By daybreak on March 2, 1980, Parnell had been arrested on suspicion of abducting both boys. After the police checked into Parnell's background they found a previous sodomy conviction from 1951.[14] Both children were reunited with their families that day. In 1981, Parnell was tried and convicted of kidnapping White and Stayner in two separate trials. He was sentenced to seven years but was paroled after serving five years.[15][16] Parnell was not charged with the numerous sexual assaults on Steven Stayner and other boys because most of them occurred outside the jurisdiction of the Merced county prosecutor or were by then outside the statute of limitations. The Mendocino County prosecutors, acting almost entirely alone, decided not to prosecute Parnell for the sexual assaults that occurred in their jurisdiction. This is likely due to the prosecutors' belief that they were "protecting" Stayner because rape and molestation victims were seen as "damaged goods." They may also have felt that they were respecting the Stayner parents' reluctance to discuss Parnell's crimes because of the stigma of male sexual abuse.[17] Poorman, who had helped abduct Timmy White, and Ervin Murphy were convicted of lesser charges. Both claimed they knew nothing of the sexual assaults on Steven. Barbara Mathias was never arrested.[18] Stayner remembered the kindness "Uncle" Murphy had shown him in his first week of captivity while they were both under the influence of Parnell's manipulation, and he believed that Murphy was as much Parnell's victim as Steven and Timmy were.[19]

Steven Stayner's kidnapping and its aftermath prompted California lawmakers to change state laws "to allow consecutive prison terms in similar abduction cases."[20]

Later life and death

After returning to his family, Stayner had trouble adjusting to a more structured household as he had been allowed to smoke, drink and do as he pleased when he lived with Kenneth Parnell.[21] In an interview with Newsweek shortly after he was reunited with his family, Stayner said, "I returned almost a grown man and yet my parents saw me at first as their 7-year-old. After they stopped trying to teach me the fundamentals all over again, it got better. But why doesn't my dad hug me anymore? [...] Everything has changed. Sometimes I blame myself. I don't know sometimes if I should have come home. Would I have been better off if I didn't?"[22] Stayner initially underwent brief counseling but never sought additional treatment. He also refused to disclose all the details of sexual abuse he endured while he was living with Kenneth Parnell.[21] In a 2007 interview, Stayner's sister Cory said that her brother did not seek counseling because their father said Stayner "didn't need any". She added, "He [Steven] got on with his life but he was pretty messed up." He was teased by other children at school for being molested and eventually dropped out. Stayner began to drink frequently and suppressed his true feelings. He was eventually kicked out of the family home and his relationship with his father remained strained.[22]

In 1985, Stayner married 17-year-old Jody Edmondson.[2] The couple had two children, Ashley and Steven, Jr.[23] Jody Edmondson later said that having a family of his own helped Stayner find some peace although he still blamed himself for being abducted. In his final years, Stayner worked with child abduction groups, spoke to children about stranger danger and granted interviews about his kidnapping.[22] He later joined The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints just before his death.[24] At the time of his death, Stayner was living in Merced, California and working at Pizza Hut.[22][25]

On September 17, 1989, Stayner was heading home from work on a rainy afternoon when his motorcycle collided with a car that pulled into traffic from a side road in Merced, California. He sustained fatal head injuries and died at the Merced Community Medical Center shortly thereafter. At the time of the accident, Stayner was driving without a license and was not wearing a helmet.[25] The driver who struck Stayner fled from the scene and later surrendered to police shortly before Stayner's funeral.[26]

On September 20, Stayner's funeral was held at the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in Merced.[26] 500 people attended including 14-year-old Timmy White who was one of Stayner's pallbearers.[27][26]

Media adaptations

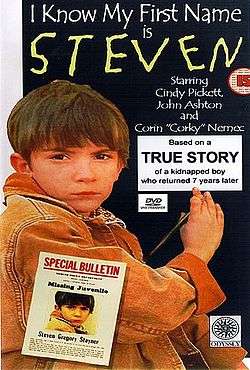

| I Know My First Name is Steven | |

|---|---|

| |

| Genre | Docudrama |

| Written by |

Mike Echols J.P. Miller Cynthia Whitcomb |

| Directed by | Larry Elikann |

| Starring |

Corin Nemec Luke Edwards Arliss Howard Cindy Pickett John Ashton |

| Theme music composer | David Shire |

| Country of origin | United States |

| Original language(s) | English |

| Production | |

| Producer(s) | Kim C. Friese |

| Editor(s) |

David Ramirez Peter V. White |

| Running time | 180 mins. |

| Release | |

| Original network | NBC |

| Original release | May 21, 1989 – May 22, 1989 |

In early 1989, a television miniseries based on his experience, I Know My First Name is Steven (also known as The Missing Years), was produced. Steven, taking a leave of absence from his job, acted as an advisor for the production company (Lorimar-Telepictures) and had a non-speaking part, playing one of the two policemen who escort 14-year-old Steven (played by Corin Nemec) through the crowds to his waiting family, on his return to his Merced home. Although pleased with the dramatization, Stayner did complain that it depicted him as a somewhat "obnoxious, rude" person, especially toward his parents, something he refuted while publicizing the miniseries in the spring of 1989.[28] The two-part miniseries was first broadcast in the USA by NBC on May 21–22, 1989.[29] Screening rights were sold to a number of international television companies including the BBC, which screened the miniseries in mid-July of the following year; later still, it was released as a feature-length movie.[30]

The production was based on a manuscript by Mike Echols, who had researched the story and interviewed Stayner and Parnell, among others. After the premiere of I Know My First Name is Steven, which received four Emmy Award nominations, including one for Corin Nemec,[26] Echols published his book I Know My First Name is Steven in 1991. In the epilogue to his book, Echols describes how he infiltrated NAMBLA.

In 1999, against the wishes of the Stayner family, Echols wrote an additional chapter, about Steven's older brother, convicted serial killer Cary Stayner, at the request of his publisher who then re-published the book.[31]

The title of the film and book are taken from the first paragraph of Steven's written police statement, given during the early hours of March 2, 1980 in Ukiah. It reads (note the incorrect spelling of his family name);[32]

"My name is Steven Stainer [sic]. I am fourteen years of age. I don't know my true birthdate, but I use April 18, 1965. I know my first name is Steven, I'm pretty sure my last is Stainer [sic], and if I have a middle name, I don't know it."

Steven's story was also included in the book Against Their Will by Nigel Cawthorne, a compilation of stories of kidnappings.[33]

Aftermath

Ten years after Stayner's death, the city of Merced asked its residents to propose names for city parks honoring Merced's notable citizens. Stayner's parents proposed that one be named "Stayner Park". This idea was eventually rejected and the honor was instead given to another Merced resident because Stayner's brother Cary confessed to, and was charged with, the 1999 Yosemite multiple murders, amid fears that the name "Stayner Park" would be associated with Cary rather than Steven.[34]

In 2004, Kenneth Parnell, then 72 years of age, was convicted of trying the previous year to persuade his nurse to procure for him a young boy for five hundred dollars. The nurse, aware of Parnell's past, reported this to local police. Timmy White, then a grown man, was subpoenaed to testify in Parnell's criminal trial. Although Stayner was dead, Stayner's testimony at Parnell's earlier trial was read to jurors as evidence in Parnell's 2004 trial.[35] Kenneth Parnell died of natural causes on January 21, 2008, at the California State Prison Hospital in Vacaville, California, while serving a 25-years-to-life sentence.[36]

Timothy James "Timmy" White later became a Los Angeles County Sheriff's Department Deputy. He died on April 1, 2010, at age 35 from pulmonary embolism. White was survived by his wife, Dena, and two young children, as well as by his mother, father, stepfather and sister.[37][38] Nearly five months later, on August 28, 2010, a statue of Stayner and White was dedicated in Applegate Park in Merced, California.[39] Residents of Ukiah, the hometown of White, carved a statue showing a teenage Stayner with young White in hand while escaping their captivity.[40] Fundraisers for the statue have stated that it is meant to honor Steven Stayner and give families of missing and kidnapped children hope that they are still alive.[40]

Steven's father, Delbert Stayner, died on April 9, 2013 at his home in Winton, California. He was 79 years old.

References

- ↑ "Steven Stayner lived courageously". Lodi News-Sentinel. October 3, 1989. p. 2. Retrieved May 1, 2014.

- 1 2 "Crash ends life scarred by childhood abduction". The Spokesman-Review. September 18, 1989. p. A3. Retrieved May 1, 2014.

- ↑ Curtis, Kim (January 5, 2003). "The Legend of Peggy Hopkins Joyce: She Collected Men, Chinchilla, Diamonds". The Southeast Missourian. p. 8A. Retrieved May 1, 2014.

- 1 2 3 Echols, Mike (1999). I Know My First Name Is Steven. Pinnacle. p. 41. ISBN 0-7860-1104-1.

- ↑ Echols 1999, pp. 38-39

- 1 2 3 Echols 1999, p. 85

- 1 2 Echols 1991, p. 42

- ↑ Echols 1991, p. 95

- ↑ Echols 1999, p. 48

- ↑ Echols 1999, pp. 91-92

- ↑ Echols 1999, p. 91

- ↑ Echols 1999, pp. 90-91

- ↑ David Peterson (March 21, 1980). "Kidnap victim reunites with 'mystery woman'". St. Petersburg Times, United Press International. Retrieved September 15, 2009.

- 1 2 "Suspect once sex offender". Lodi News-Sentinel. March 4, 1980. p. 1. Retrieved May 1, 2014.

- ↑ "Alleged attempt to buy child leads to arrest of kidnapper". CNN. January 4, 2003. Retrieved August 17, 2008.

- ↑ Steven Stayner, serial killer Cary Stayner's brother, was abducted for 7 years - Crime Library on truTV.com

- ↑ St. Clair, Katy (January 15, 2003). "Inside the Monster". eastbayexpress.com. East Bay Express. Retrieved May 1, 2014.

- ↑ Echols 1999 pp.250-291

- ↑ Echols 1999 p.291

- ↑ Ramirez, Jessica. "The Abductions That Changed America", Newsweek, January 29, 2007, pp. 54–55.

- 1 2 Schindehette, Susan; Adelson, Suzanne (May 22, 1989). "17 Years Later, a Tv Miniseries Forces Steven Stayner to Relive the Horror of His Childhood". people.com. People magazine. Retrieved May 1, 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 Holland, Elizabethe (January 20, 2007). "A child abductee's journey back". seattletimes.com. The Seattle Times. Retrieved May 1, 2014.

- ↑ "Remembering Stephen Stayner". mercedsunstar.com. Merced Sun-Star. September 4, 2009. Retrieved May 1, 2014.

- ↑ "Mormon News for WE 01Aug99: Stayner family's woeful history". mormonstoday.com.

- 1 2 "Crash ends life scarred by childhood abduction". The Spokesman-Review. September 18, 1989. p. A1. Retrieved May 1, 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 Stark, John; Adelson, Suzanne (October 2, 1989). "A Hit-and-Run Crash Ends the Life of Kidnap Victim Steven Stayner". people.com. People magazine. Retrieved May 1, 2014.

- ↑ Cawthorne, Nigel (2012). Against Their Will: Sadistic Kidnappers and the Courageous Stories of Their Innocent Victims. Ulysses Press. p. 245. ISBN 1-612-43066-X.

- ↑ Blua, Elenor. New York Times May 22, 1989

- ↑ A.P syndicated report printed in the New York Times September 18, 1989

- ↑ I Know My First Name is Steven at the Internet Movie Database

- ↑ Article by Tim Bragg (staff writer) printed in the Merced Sun-Star newspaper, Aug. 1999.

- ↑ Echols 1999 p. 212

- ↑ Cawthorne, Nigel (2012). Against their will : sadistic kidnappers and the courageous stories of their innocent victims. Berkeley, CA: Ulysses Press. 221 pp. ISBN 978-1612430669.

- ↑ MacGowan, Douglas. "The Lost Boy", CourtTV's Crime Library

- ↑ "'Steven' kidnapper convicted". CNN. February 9, 2004. Archived from the original on 2008-06-03. Retrieved 2008-08-17.

- ↑ "Kenneth Parnell, kidnapper of Steven Stayner, dies at 76", San Francisco Chronicle, Jan 22, 2008

- ↑ "Ukiah Daily Journal: Timothy White, boy saved by Steven Stayner, dead at 35". mercedsunstar.com. Merced Sun-Star. April 8, 2010. Retrieved May 1, 2014.

- ↑ "Timothy White, victim of 1980 kidnapping, dies". signalscv.com.

- ↑ Patton, Victor A. (August 30, 2010). "Statue honors Steven Stayner's legacy". Merced Sun-Star. Retrieved March 27, 2012.

- 1 2 Steven Stayner memorial

Further reading

- I Know My First Name Is Steven, by Mike Echols. Pinnacle Books, New York. 1999. ISBN 0-7860-1104-1

- From Victim To Hero: The Untold Story of Steven Stayner, by Jim Laughter assisted by Sharon Carr Griffen. Buoy Up Press, Denton, Texas, 2010. ISBN 978-0-937660-86-7

External links

|