Steiner system

In combinatorial mathematics, a Steiner system (named after Jakob Steiner) is a type of block design, specifically a t-design with λ = 1 and t ≥ 2.

A Steiner system with parameters t, k, n, written S(t,k,n), is an n-element set S together with a set of k-element subsets of S (called blocks) with the property that each t-element subset of S is contained in exactly one block. In an alternate notation for block designs, an S(t,k,n) would be a t-(n,k,1) design.

This definition is relatively modern, generalizing the classical definition of Steiner systems which in addition required that k = t + 1. An S(2,3,n) was (and still is) called a Steiner triple (or triad) system, while an S(3,4,n) was called a Steiner quadruple system, and so on. With the generalization of the definition, this naming system is no longer strictly adhered to.

A long-standing problem in design theory is if any nontrivial (t < k < n) Steiner systems have t ≥ 6; also if infinitely many have t = 4 or 5.[1] This was claimed to be solved in the affirmative by Peter Keevash.[2][3]

Examples

Finite projective planes

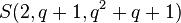

A finite projective plane of order q, with the lines as blocks, is an  , since it has

, since it has  points, each line passes through

points, each line passes through  points, and each pair of distinct points lies on exactly one line.

points, and each pair of distinct points lies on exactly one line.

Finite affine planes

A finite affine plane of order q, with the lines as blocks, is an S(2, q, q2). An affine plane of order q can be obtained from a projective plane of the same order by removing one block and all of the points in that block from the projective plane. Choosing different blocks to remove in this way can lead to non-isomorphic affine planes.

Classical Steiner systems

Steiner triple systems

An S(2,3,n) is called a Steiner triple system, and its blocks are called triples. It is common to see the abbreviation STS(n) for a Steiner triple system of order n.

The number of triples is n(n−1)/6. A necessary and sufficient condition for the existence of an S(2,3,n) is that n  1 or 3 (mod 6). The projective plane of order 2 (the Fano plane) is an STS(7) and the affine plane of order 3 is an STS(9).

1 or 3 (mod 6). The projective plane of order 2 (the Fano plane) is an STS(7) and the affine plane of order 3 is an STS(9).

Up to isomorphism, the STS(7) and STS(9) are unique, there are two STS(13)s, 80 STS(15)s, and 11,084,874,829 STS(19)s.[4]

We can define a multiplication on the set S using the Steiner triple system by setting aa = a for all a in S, and ab = c if {a,b,c} is a triple. This makes S an idempotent, commutative quasigroup. It has the additional property that "ab" = "c" implies "bc" = "a" and "ca" = "b".[5] Conversely, any (finite) quasigroup with these properties arises from a Steiner triple system. Commutative idempotent quasigroups satisfying this additional property are called Steiner quasigroups.[6]

Steiner quadruple systems

An S(3,4,n) is called a Steiner quadruple system. A necessary and sufficient condition for the existence of an S(3,4,n) is that n  2 or 4 (mod 6). The abbreviation SQS(n) is often used for these systems.

2 or 4 (mod 6). The abbreviation SQS(n) is often used for these systems.

Up to isomorphism, SQS(8) and SQS(10) are unique, there are 4 SQS(14)s and 1,054,163 SQS(16)s.[7]

Steiner quintuple systems

An S(4,5,n) is called a Steiner quintuple system. A necessary condition for the existence of such a system is that n  3 or 5 (mod 6) which comes from considerations that apply to all the classical Steiner systems. An additional necessary condition is that n

3 or 5 (mod 6) which comes from considerations that apply to all the classical Steiner systems. An additional necessary condition is that n  4 (mod 5), which comes from the fact that the number of blocks must be an integer. Sufficient conditions are not known.

4 (mod 5), which comes from the fact that the number of blocks must be an integer. Sufficient conditions are not known.

There is a unique Steiner quintuple system of order 11, but none of order 15 or order 17.[8] Systems are known for orders 23, 35, 47, 71, 83, 107, 131, 167 and 243. The smallest order for which the existence is not known (as of 2011) is 21.

Properties

It is clear from the definition of S(t,k,n) that  . (Equalities, while technically possible, lead to trivial systems.)

. (Equalities, while technically possible, lead to trivial systems.)

If S(t,k,n) exists, then taking all blocks containing a specific element and discarding that element gives a derived system S(t−1,k−1,n−1). Therefore the existence of S(t−1,k−1,n−1) is a necessary condition for the existence of S(t,k,n).

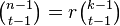

The number of t-element subsets in S is  , while the number of t-element subsets in each block is

, while the number of t-element subsets in each block is  . Since every t-element subset is contained in exactly one block, we have

. Since every t-element subset is contained in exactly one block, we have  , or

, or  , where b is the number of blocks. Similar reasoning about t-element subsets containing a particular element gives us

, where b is the number of blocks. Similar reasoning about t-element subsets containing a particular element gives us  , or

, or  , where r is the number of blocks containing any given element. From these definitions follows the equation

, where r is the number of blocks containing any given element. From these definitions follows the equation  . It is a necessary condition for the existence of S(t,k,n) that b and r are integers. As with any block design, Fisher's inequality

. It is a necessary condition for the existence of S(t,k,n) that b and r are integers. As with any block design, Fisher's inequality  is true in Steiner systems.

is true in Steiner systems.

Given the parameters of a Steiner system S(t,k,n) and a subset of size  , contained in at least one block, one can compute the number of blocks intersecting that subset in a fixed number of elements by constructing a Pascal triangle.[9] In particular, the number of blocks intersecting a fixed block in any number of elements is independent of the chosen block.

, contained in at least one block, one can compute the number of blocks intersecting that subset in a fixed number of elements by constructing a Pascal triangle.[9] In particular, the number of blocks intersecting a fixed block in any number of elements is independent of the chosen block.

It can be shown that if there is a Steiner system S(2,k,n), where k is a prime power greater than 1, then n  1 or k (mod k(k−1)). In particular, a Steiner triple system S(2,3,n) must have n = 6m+1 or 6m+3. It is known that this is the only restriction on Steiner triple systems, that is, for each natural number m, systems S(2,3,6m+1) and S(2,3,6m+3) exist.

1 or k (mod k(k−1)). In particular, a Steiner triple system S(2,3,n) must have n = 6m+1 or 6m+3. It is known that this is the only restriction on Steiner triple systems, that is, for each natural number m, systems S(2,3,6m+1) and S(2,3,6m+3) exist.

History

Steiner triple systems were defined for the first time by W.S.B. Woolhouse in 1844 in the Prize question #1733 of Lady's and Gentlemen's Diary.[10] The posed problem was solved by Thomas Kirkman (1847). In 1850 Kirkman posed a variation of the problem known as Kirkman's schoolgirl problem, which asks for triple systems having an additional property (resolvability). Unaware of Kirkman's work, Jakob Steiner (1853) reintroduced triple systems, and as this work was more widely known, the systems were named in his honor.

Mathieu groups

Several examples of Steiner systems are closely related to group theory. In particular, the finite simple groups called Mathieu groups arise as automorphism groups of Steiner systems:

- The Mathieu group M11 is the automorphism group of a S(4,5,11) Steiner system

- The Mathieu group M12 is the automorphism group of a S(5,6,12) Steiner system

- The Mathieu group M22 is the unique index 2 subgroup of the automorphism group of a S(3,6,22) Steiner system

- The Mathieu group M23 is the automorphism group of a S(4,7,23) Steiner system

- The Mathieu group M24 is the automorphism group of a S(5,8,24) Steiner system.

The Steiner system S(5, 6, 12)

There is a unique S(5,6,12) Steiner system; its automorphism group is the Mathieu group M12, and in that context it is denoted by W12.

Constructions

There are different ways to construct an S(5,6,12) system.

Projective line method

This construction is due to Carmichael (1937).[11]

Add a new element, call it ∞, to the 11 elements of the finite field F11 (that is, the integers mod 11). This set, S, of 12 elements can be formally identified with the points of the projective line over F11. Call the following specific subset of size 6,

a "block". From this block, we obtain the other blocks of the S(5,6,12) system by repeatedly applying the linear fractional transformations:

With the usual conventions of defining f (−d/c) = ∞ and f (∞) = a/c, these functions map the set S onto itself. In geometric language, they are projectivities of the projective line. They form a group under composition which is the projective special linear group PSL(2,11) of order 660. There are exactly five elements of this group that leave the starting block fixed setwise,[12] so there will be 132 images of that block. As a consequence of the multiply transitive property of this group acting on this set, any subset of five elements of S will appear in exactly one of these 132 images of size six.

Kitten method

An alternative construction of W12 is obtained by use of the 'kitten' of R.T. Curtis,[13] which was intended as a "hand calculator" to write down blocks one at a time. The kitten method is based on completing patterns in a 3x3 grid of numbers, which represent an affine geometry on the vector space F3xF3, an S(2,3,9) system.

Construction from K6 graph factorization

The relations between the graph factors of the complete graph K6 generate an S(5,6,12).[14] A K6 graph has 6 different 1-factorizations (ways to partition the edges into disjoint perfect matchings), and also 6 vertices. The set of vertices and the set of factorizations provide one block each. For every distinct pair of factorizations, there exists exactly one perfect matching in common. Take the set of vertices and replace the two vertices corresponding to an edge of the common perfect matching with the labels corresponding to the factorizations; add that to the set of blocks. Repeat this with the other two edges of the common perfect matching. Similarly take the set of factorizations and replace the labels corresponding to the two factorizations with the end points of an edge in the common perfect matching. Repeat with the other two edges in the matching. There are thus 3+3 = 6 blocks per pair of factorizations, and there are 6C2 = 15 pairs among the 6 factorizations, resulting in 90 new blocks. Finally take the full set of 12C6 = 924 combinations of 6 objects out of 12, and discard any combination that has 5 or more objects in common with any of the 92 blocks generated so far. Exactly 40 blocks remain, resulting in 2+90+40 = 132 blocks of the S(5,6,12).

The Steiner system S(5, 8, 24)

The Steiner system S(5, 8, 24), also known as the Witt design or Witt geometry, was first described by Carmichael (1931) and rediscovered by Witt (1938). This system is connected with many of the sporadic simple groups and with the exceptional 24-dimensional lattice known as the Leech lattice.

The automorphism group of S(5, 8, 24) is the Mathieu group M24, and in that context the design is denoted W24 ("W" for "Witt")

Constructions

There are many ways to construct the S(5,8,24). Two methods are described here:

Method based on 8-combinations of 24 elements

All 8-element subsets of a 24-element set are generated in lexicographic order, and any such subset which differs from some subset already found in fewer than four positions is discarded.

The list of octads for the elements 01, 02, 03, ..., 22, 23, 24 is then:

- 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08

- 01 02 03 04 09 10 11 12

- 01 02 03 04 13 14 15 16

- .

- . (next 753 octads omitted)

- .

- 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20

- 13 14 15 16 21 22 23 24

- 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24

Each single element occurs 253 times somewhere in some octad. Each pair occurs 77 times. Each triple occurs 21 times. Each quadruple (tetrad) occurs 5 times. Each quintuple (pentad) occurs once. Not every hexad, heptad or octad occurs.

Method based on 24-bit binary strings

All 24-bit binary strings are generated in lexicographic order, and any such string that differs from some earlier one in fewer than 8 positions is discarded. The result looks like this:

000000000000000000000000

000000000000000011111111

000000000000111100001111

000000000000111111110000

000000000011001100110011

000000000011001111001100

000000000011110000111100

000000000011110011000011

000000000101010101010101

000000000101010110101010

.

. (next 4083 24-bit strings omitted)

.

111111111111000011110000

111111111111111100000000

111111111111111111111111

The list contains 4096 items, which are each code words of the extended binary Golay code. They form a group under the XOR operation. One of them has zero 1-bits, 759 of them have eight 1-bits, 2576 of them have twelve 1-bits, 759 of them have sixteen 1-bits, and one has twenty-four 1-bits. The 759 8-element blocks of the S(5,8,24) (called octads) are given by the patterns of 1's in the code words with eight 1-bits.

See also

Notes

- ↑ "Encyclopaedia of Design Theory: t-Designs". Designtheory.org. 2004-10-04. Retrieved 2012-08-17.

- ↑ Keevash, Peter (2014). "The existence of designs". arXiv:1401.3665.

- ↑ "A Design Dilemma Solved, Minus Designs". Quanta Magazine. 2015-06-09. Retrieved 2015-06-27.

- ↑ Colbourn & Dinitz 2007, pg.60

- ↑ This property is equivalent to saying that (xy)y = x for all x and y in the idempotent commutative quasigroup.

- ↑ Colbourn & Dinitz 2007, pg. 497, definition 28.12

- ↑ Colbourn & Dinitz 2007, pg.106

- ↑ Östergard & Pottonen 2008

- ↑ Assmus & Key 1994, pg. 8

- ↑ Lindner & Rodger 1997, pg.3

- ↑ Carmichael 1956, p. 431

- ↑ Beth, Jungnickel & Lenz 1986, p. 196

- ↑ Curtis 1984

- ↑ EAGTS textbook

References

- Assmus, E. F., Jr.; Key, J. D. (1994), "8. Steiner Systems", Designs and Their Codes, Cambridge University Press, pp. 295–316, ISBN 0-521-45839-0.

- Beth, Thomas; Jungnickel, Dieter; Lenz, Hanfried (1986), Design Theory, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 2nd ed. (1999) ISBN 978-0-521-44432-3.

- Carmichael, Robert (1931), "Tactical Configurations of Rank Two", American Journal of Mathematics 53: 217–240, doi:10.2307/2370885

- Carmichael, Robert D. (1956) [1937], Introduction to the theory of Groups of Finite Order, Dover, ISBN 0-486-60300-8

- Colbourn, Charles J.; Dinitz, Jeffrey H. (1996), Handbook of Combinatorial Designs, Boca Raton: Chapman & Hall/ CRC, ISBN 0-8493-8948-8, Zbl 0836.00010

- Colbourn, Charles J.; Dinitz, Jeffrey H. (2007), Handbook of Combinatorial Designs (2nd ed.), Boca Raton: Chapman & Hall/ CRC, ISBN 1-58488-506-8, Zbl 1101.05001

- Curtis, R.T. (1984), "The Steiner system S(5,6,12), the Mathieu group M12 and the "kitten"", in Atkinson, Michael D., Computational group theory (Durham, 1982), London: Academic Press, pp. 353–358, ISBN 0-12-066270-1, MR 0760669

- Hughes, D. R.; Piper, F. C. (1985), Design Theory, Cambridge University Press, pp. 173–176, ISBN 0-521-35872-8.

- Kirkman, Thomas P. (1847), "On a Problem in Combinations", The Cambridge and Dublin Mathematical Journal (Macmillan, Barclay, and Macmillan) II: 191–204.

- Lindner, C.C.; Rodger, C.A. (1997), Design Theory, Boca Raton: CRC Press, ISBN 0-8493-3986-3

- Östergard, Patric R.J.; Pottonen, Olli (2008), "There exists no Steiner system S(4,5,17)", Journal of Combinatorial Theory Series A 115 (8): 1570–1573, doi:10.1016/j.jcta.2008.04.005

- Steiner, J. (1853), "Combinatorische Aufgabe", Journal für die Reine und Angewandte Mathematik 45: 181–182.

- Witt, Ernst (1938), "Die 5-Fach transitiven Gruppen von Mathieu", Abh. Math. Sem. Univ. Hamburg 12: 256–264, doi:10.1007/BF02948947

External links

- Rowland, Todd and Weisstein, Eric W., "Steiner System", MathWorld.

- Rumov, B.T. (2001), "Steiner system", in Hazewinkel, Michiel, Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer, ISBN 978-1-55608-010-4

- Steiner systems by Andries E. Brouwer

- Implementation of S(5,8,24) by Dr. Alberto Delgado, Gabe Hart, and Michael Kolkebeck

- S(5, 8, 24) Software and Listing by Johan E. Mebius

- The Witt Design computed by Ashay Dharwadker