Stationary state

In quantum mechanics, a stationary state is an eigenvector of the Hamiltonian, implying the probability density associated with the wavefunction is independent of time.[1] This corresponds to a quantum state with a single definite energy (instead of a quantum superposition of different energies). It is also called energy eigenvector, energy eigenstate, energy eigenfunction, or energy eigenket. It is very similar to the concept of atomic orbital and molecular orbital in chemistry, with some slight differences explained below.

Introduction

A stationary state is called stationary because the system remains in the same state as time elapses, in every observable way. For a single-particle Hamiltonian, this means that the particle has a constant probability distribution for its position, its velocity, its spin, etc.[2] (This is true assuming the particle's environment is also static, i.e. the Hamiltonian is unchanging in time.) The wavefunction itself is not stationary: It continually changes its overall complex phase factor, so as to form a standing wave. The oscillation frequency of the standing wave, times Planck's constant, is the energy of the state according to the Planck–Einstein relation.

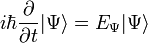

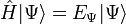

Stationary states are quantum states that are solutions to the time-independent Schrödinger equation:

,

,

where

is a quantum state, which is a stationary state if it satisfies this equation;

is a quantum state, which is a stationary state if it satisfies this equation; is the Hamiltonian operator;

is the Hamiltonian operator; is a real number, and corresponds to the energy eigenvalue of the state

is a real number, and corresponds to the energy eigenvalue of the state  .

.

This is an eigenvalue equation:  is a linear operator on a vector space,

is a linear operator on a vector space,  is an eigenvector of

is an eigenvector of  , and

, and  is its eigenvalue.

is its eigenvalue.

If a stationary state  is plugged into the time-dependent Schrödinger Equation, the result is:[3]

is plugged into the time-dependent Schrödinger Equation, the result is:[3]

Assuming that  is time-independent (unchanging in time), this equation holds for any time t. Therefore this is a differential equation describing how

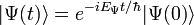

is time-independent (unchanging in time), this equation holds for any time t. Therefore this is a differential equation describing how  varies in time. Its solution is:

varies in time. Its solution is:

Therefore a stationary state is a standing wave that oscillates with an overall complex phase factor, and its oscillation angular frequency is equal to its energy divided by  .

.

Stationary state properties

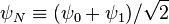

, which is not a stationary state. The right column illustrates why stationary states are called "stationary".

, which is not a stationary state. The right column illustrates why stationary states are called "stationary".As shown above, a stationary state is not mathematically constant:

However, all observable properties of the state are in fact constant. For example, if  represents a simple one-dimensional single-particle wavefunction

represents a simple one-dimensional single-particle wavefunction  , the probability that the particle is at location x is:

, the probability that the particle is at location x is:

which is independent of the time t.

The Heisenberg picture is an alternative mathematical formulation of quantum mechanics where stationary states are truly mathematically constant in time.

As mentioned above, these equations assume that the Hamiltonian is time-independent. This means simply that stationary states are only stationary when the rest of the system is fixed and stationary as well. For example, a 1s electron in a hydrogen atom is in a stationary state, but if the hydrogen atom reacts with another atom, then the electron will of course be disturbed.

Spontaneous decay

Spontaneous decay complicates the question of stationary states. For example, according to simple (nonrelativistic) quantum mechanics, the hydrogen atom has many stationary states: 1s, 2s, 2p, and so on, are all stationary states. But in reality, only the ground state 1s is truly "stationary": An electron in a higher energy level will spontaneously emit one or more photons to decay into the ground state.[4] This seems to contradict the idea that stationary states should have unchanging properties.

The explanation is that the Hamiltonian used in nonrelativistic quantum mechanics is only an approximation to the Hamiltonian from quantum field theory. The higher-energy electron states (2s, 2p, 3s, etc.) are stationary states according to the approximate Hamiltonian, but not stationary according to the true Hamiltonian, because of vacuum fluctuations. On the other hand, the 1s state is truly a stationary state, according to both the approximate and the true Hamiltonian.

Comparison to "orbital" in chemistry

An orbital is a stationary state (or approximation thereof) of a one-electron atom or molecule; more specifically, an atomic orbital for an electron in an atom, or a molecular orbital for an electron in a molecule.[5]

For a molecule that contains only a single electron (e.g. atomic hydrogen or H2+), an orbital is exactly the same as a total stationary state of the molecule. However, for a many-electron molecule, an orbital is completely different from a total stationary state, which is a many-particle state requiring a more complicated description (such as a Slater determinant). In particular, in a many-electron molecule, an orbital is not the total stationary state of the molecule, but rather the stationary state of a single electron within the molecule. This concept of an orbital is only meaningful under the approximation that if we ignore the electron-electron repulsion terms in the Hamiltonian as a simplifying assumption, we can decompose the total eigenvector of a many-electron molecule into separate contributions from individual electron stationary states (orbitals), each of which are obtained under the one-electron approximation. (Luckily, chemists and physicists can often (but not always) use this "single-electron approximation.") In this sense, in a many-electron system, an orbital can be considered as the stationary state of an individual electron in the system.

In chemistry, calculation of molecular orbitals typically also assume the Born–Oppenheimer approximation.

See also

- Transition of state

- Quantum number

- Quantum mechanic vacuum or vacuum state

- Virtual particle

- Steady State

References

- ↑ Quantum Mechanics Demystified, D. McMahon, Mc Graw Hill (USA), 2006, ISBN 0-07-145546-9

- ↑ Cohen-Tannoudji, Claude, Bernard Diu, and Franck Laloë. Quantum Mechanics: Volume One. Hermann, 1977. p. 32.

- ↑ Quanta: A handbook of concepts, P.W. Atkins, Oxford University Press, 1974, ISBN 0-19-855493-1

- ↑ Quantum Physics of Atoms, Molecules, Solids, Nuclei, and Particles (2nd Edition), R. Eisberg, R. Resnick, John Wiley & Sons, 1985, ISBN 978-0-471-87373-0

- ↑ Physical chemistry, P.W. Atkins, Oxford University Press, 1978, ISBN 0-19-855148-7

Further reading

- Stationary states, Alan Holden, Oxford University Press, 1971, ISBN 0-19-851121-3