Philip the Apostle

| Philip the Apostle | |

|---|---|

St. Philip, by Peter Paul Rubens, from his Twelve Apostles series (c. 1611), at the Museo del Prado, Madrid | |

| Apostle and Martyr | |

| Born | Bethsaida, Galilee, Roman Empire |

| Died |

80 A.D Hierapolis, Anatolia, Roman Empire |

| Venerated in |

Christianity Islam (named in exegesis) |

| Canonized | Pre-congregation |

| Feast | 3 May (Roman Catholic Church),[1] 14 November (Eastern Orthodox Church), 1 May (Anglican Communion, Lutheran Church and pre-1955 General Roman Calendar), 11 May (General Roman Calendar, 1955–69) |

| Attributes | Elderly, bearded saint and open-to-God man, holding a basket of loaves and a Tau cross |

| Patronage | Cape Verde; Hatters; Pastry chefs; San Felipe Pueblo; Uruguay |

Philip the Apostle (Greek: Φίλιππος, Philippos) was one of the Twelve Apostles of Jesus. Later Christian traditions describe Philip as the apostle who preached in Greece, Syria, and Phrygia.

In the Roman Catholic Church, the feast day of Philip, along with that of James the Just, was traditionally observed on 1 May, the anniversary of the dedication of the church dedicated to them in Rome (now called the Church of the Twelve Apostles). The Eastern Orthodox Church celebrates Philip's feast day on 14 November. One of the Gnostic codices discovered in the Nag Hammadi library in 1945 bears Philip's name in its title, on the bottom line. [2]

New Testament

The Synoptic Gospels list Philip as one of the apostles. The Gospel of John describes Philip's calling as a disciple of Jesus.[Jn 1:43] Philip is described as a disciple from the city of Bethsaida, and connects him to Andrew and Peter, who were from the same town. He also was among those surrounding the Baptist when the latter first pointed out Jesus as the Lamb of God. It was Philip who first introduces Nathanael (sometimes identified with Bartholomew) to Jesus.[3] According to Butler, Philip was among those attending the wedding at Cana.[1]

Of the four Gospels, Philip figures most prominently in the Gospel of John. Philip is asked by Jesus how to feed 5,000 people.[3] Later he appears as a link to the Greek community. Philip bore a Greek name and may have spoken Greek. He advises Andrew that certain Greeks wish to meet Jesus, and together they inform him of this.[3] During the Last Supper, when Philip asked Jesus to show them the Father, he provides Jesus the opportunity to teach his disciples about the unity of the Father and the Son.[1]

Philip the Apostle should not be confused with Philip the Evangelist, who was appointed with Stephen to oversee charitable distributions. (Acts 6:5)

Christian tradition

_-_James_Tissot_-_overall.jpg)

Accounts of Philip's life and ministry exist in the extra-canonical writings of later Christians. However, some can be misleading, as many hagiographers conflated Philip the Apostle with Philip the Evangelist. The most notable and influential example of this is the hagiography of Eusebius, in which Eusebius clearly assumes that both Philips are the same person.[4] As early as 1260, Jacobus de Voragine noted in his Golden Legend that the account of Philip's life given by Eusebius was not to be trusted.[5]

An early story about St Philip is preserved in the Letter from Peter to Philip, one of the texts in the Nag Hammadi Library, and dated to the end of the 2nd century or early 3rd.[6] This text begins with a letter from St Peter to Philip the apostle, asking him to rejoin the other apostles who had gathered at the Mount of Olives. Fred Lapham believes that this letter indicates an early tradition that "at some point between the Resurrection of Jesus and the final parting of his risen presence from the disciples, Philip had undertaken a sole missionary enterprise, and was, for some reason, reluctant to return to the rest of the Apostles." This mission is in harmony with the later tradition that each disciple was given a specific missionary charge.[7] Lapham explains the central section, a Gnostic dialogue between the risen Christ and his disciples, as a later insertion.[8]

Later stories about Saint Philip's life can be found in the anonymous Acts of Philip, probably written by a contemporary of Eusebius.[9] This non-canonical book recounts the preaching and miracles of Philip. Following the resurrection of Jesus, Philip was sent with his sister Mariamne and Bartholomew to preach in Greece, Phrygia, and Syria.[10] Included in the Acts of Philip is an appendix, entitled "Of the Journey of Philip the Apostle: From the Fifteenth Act Until the End, and Among Them the Martyrdom." This appendix gives an account of Philip's martyrdom in the city of Hierapolis.[11] According to this account, through a miraculous healing and his preaching Philip converted the wife of the proconsul of the city. This enraged the proconsul, and he had Philip, Bartholomew, and Mariamne all tortured. Philip and Bartholomew were then crucified upside-down, and Philip preached from his cross. As a result of Philip's preaching the crowd released Bartholomew from his cross, but Philip insisted that they not release him, and Philip died on the cross. Another legend is that he was martyred by beheading in the city of Hierapolis.

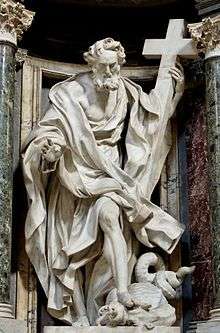

Iconography

Philip is commonly associated with the symbol of the Latin cross.[12] Other symbols assigned to Philip include: the cross with the two loaves (because of his answer to the Lord in John 6:7), a basket filled with bread, a spear with the patriarchal cross, and a cross with a carpenter's square.[13]

Patronage

Saint Philip is the patron saint of hatters.

Tomb discovered

On Wednesday, 27 July 2011, the Turkish news agency Anadolu reported that archaeologists had unearthed a tomb that the project leader claims to be the Tomb of Saint Philip during excavations in Hierapolis close to the Turkish city Denizli. The Italian archaeologist, Professor Francesco D'Andria stated that scientists had discovered the tomb within a newly revealed church. He stated that the design of the Tomb, and writings on its walls, definitively prove it belonged to the martyred Apostle of Jesus.[14]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 Butler, Alban. "St. Philip, Apostle", The Lives or the Fathers, Martyrs and Other Principal Saints, Vol. V, D. & J. Sadlier, & Company, 1864

- ↑ Martha Lee Turner, The Gospel According to Philip: The Sources and Coherence of an Early Christian Collection, page 9 (E. J. Brill, 1996). ISBN 90-04-10443-7

- 1 2 3 "CATHOLIC ENCYCLOPEDIA: St. Philip the Apostle".

- ↑ For an example of Eusebius identifying Philip the Apostle with the Philip mentioned in Acts, see Eusebius of Caesarea, Church History, 3.31.5, retrieved 14 March 2007.

- ↑ de Voragine, Jacobus. "The Golden Legend". catholic-forum.com. Archived from the original on 23 June 2007. Retrieved 14 March 2007.

- ↑ Translated in James M. Robinson, editor, The Nag Hammadi Library (New York: HarperCollins, 1990), pp. 431-437

- ↑ Fred Lapham, An Introduction to the New Testament Apocrypha (London: T & T Clark International, 2003), p. 78

- ↑ Lapham, An Introduction, p. 80

- ↑ Craig A. Blaising, "Philip, Apostle" in The Encyclopedia of Early Christianity, ed. Everett Ferguson (New York: Garland Publishing, 1997).

- ↑ "Acts of Philip -- especially Book 8". meta-religion.com. Retrieved 14 March 2007.

- ↑ Schaff, Philip (1885). "Ante-Nicene Fathers, Volume 8". Christian Classics Ethereal Library. Retrieved 14 March 2007.

- ↑ The Apostles – Saints & Angels – Catholic Online. Catholic.org (11 June 2008). Retrieved on 28 July 2011.

- ↑ "Symbols of the Saints". clovertlcs.org. Archived from the original on 16 October 2011. Retrieved 1 September 2015.

- ↑ "Tomb of Apostle Philip Found". biblicalarchaeology.org. 16 August 2014. Retrieved 1 September 2015.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Saint Philip. |

- Catholic Encyclopedia: Apostle article regarding the title "Apostle" from The Catholic Encyclopedia

- Catholic Forum: St. Philip

- Holy, All-Praised Apostle Philip Orthodox icon and synaxarion

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|