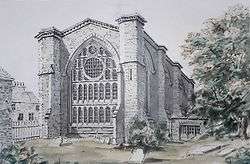

St Katharine's by the Tower

St Katharine's by the Tower—full name Royal Hospital and Collegiate Church of St. Katharine by the Tower—was a medieval church and hospital next to the Tower of London. The establishment was founded in 1147[1] and the buildings demolished in 1825 to build St Katharine Docks, which takes its name from it. It was re-established elsewhere in London and 123 years later returned once more to the East End. The church was a royal peculiar and the precinct around it was an extra-parochial area, eventually becoming a civil parish which was dissolved in 1895.

History

Medieval period

It was founded by Queen Matilda, wife of King Stephen, in 1147 in memory of two of her children, Baldwin and Matilda, who had died in infancy and been buried in the Priory Church of Holy Trinity at Aldgate.[2] Its endowment was increased by two queens consort, Eleanor of Castile (who gave a gift of manors) and Philippa of Hainault. It was made up of three brethren, three sisters (unusually, for that time, with rights equal to those of the brothers), a bedeswoman and six "poor clerks", all under a Master. It was a religious community and medieval hospital for poor infirm people next to the Tower of London. In 1273, after a dispute over its control, Queen Eleanor granted a new Charter, reserving the Foundation’s patronage to the Queens of England.[3] For 678 years, the Foundation carried on its work in East London despite periodic difficulties and renewal. In the 15th century its musical reputation rivalled that of St Paul's and in 1442 it was granted a Charter of Privileges, which made it and its 23-acre (93,000 m2) precinct a Liberty with its own prison, officers and court, all outside the City of London's ecclesiastical and civil jurisdiction.[3]

Early modern period

Its liberty status and the fact it was personally owned and protected by the Queen Mother, meant that it was not dissolved but re-established in a Protestant form. There were by now 1,000 houses (including a brewery) in its precinct, inhabited by foreigners, vagabonds and prostitutes, crammed along narrow lanes (with names like Dark Entry, Cat’s Hole, Shovel Alley, Rookery and Pillory Lane) and many in poor repair--John Stow's 1598 "Survey of London" called them "small tenements and homely cottages, having as inhabitants, English and strangers [i.e. foreigners], more in number than some city in England".[4] Since the City's guilds' restrictions did not apply here, foreign craftsmen were attracted to the Liberty, as were many seamen and rivermen. It continued to exist through the religious changes of the time: reversion to Catholicism under Mary, return to Anglicanism under Elizabeth I and the Puritan Revolution.

The status of St Katherine's appears to be ambiguous with the court leet behaving more like a select vestry. The area was successfully incorporated into the weekly Bills of mortality returns, which was not typical for extra-parochial places in London.[5]

Despite the high population density, however, in the Great Plague the Liberty's mortality rate was half of the rate in areas to the north and east of the City of London. Its continuing establishment of lay brothers and sisters, however, drew hostile attention from extreme Protestants—for example, it was only saved from being burned down by the mob in the 1780 Gordon Riots by a small group of pro-government inhabitants.

19th century and after

It grew to be a village on the banks of the River Thames outside the east walls of the Tower, offering sanctuary to immigrants and to the poor. In 1825, commercial pressure for larger docks up-river caused St Katharine’s, with its 14th & 15th century buildings and some 3,000 inhabitants, to be demolished.[6] This was to provide a dock close to the heart of the City (named St Katharine Docks after it).[7] The smallest of London's docks, some opposed the demolition of such an ancient establishment but in large part (in the words of Sir James Broodbank in his "History of the Port of London") it was also praised for demolishing "some of the most insanitary and unsalutary dwellings in London". This was without compensation and at a time when deteriorating Dickensian poverty in East London much needed St Katharine’s.

St Katharine's by the Tower was grouped into the Whitechapel District in 1855 and became a civil parish in 1866 when its extra-parochial status ended, following the Poor Law Amendment Act 1866. The parish became part of the County of London in 1889. In 1895 it was abolished as a parish and combined with St Botolph without Aldgate.

The institution, now called The Royal Foundation of St Katharine, moved to Regent's Park, where it took the form of almshouses and continued for 125 years. In 1948, St Katharine’s returned to East London to its present location in Limehouse, a mile from its original site, and became a retreat house with Father St John Groser as Master and Members of the Community of the Resurrection from Mirfield providing worship and service in the locality.[8] The Foundation remained under the care of this Community for some 45 years until 1993. In 2004, St Katharine’s modernised and expanded its facilities to include a retreat and conference centre, so making available its hospitality more widely within the Church of England and to other churches, charities, voluntary and public sector bodies and to associated individuals.

Masters of the College

John Hermesthorp fl. 1396 [9]

Burials

- Anne Stafford, Countess of March, (d. 20 September 1432)

Cultural references

The establishment forms the setting for Sir Walter Besant's novel St. Katherine's by the Tower, set in the years following the French Revolution.[10] He also deplored its demolition in his non-fiction book East London.

Population

The population of St Katharine's by the Tower at the decennial census was:[11]

| Year | 1801 | 1811 | 1821 | 1831 | 1841 | 1851 | 1871 | 1881 | 1891 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population | 2,652 | 2,706 | 2,624 | 72 | 96 | 517 | 241 | 104 | 182 |

References

- ↑ rfsk.org

- ↑ London Regent's park (1829). A picturesque guide to the Regent's park; with accurate descriptions of the Colosseum, the diorama, and the zoological gardens. p. 8. Retrieved 20 June 2013.

- 1 2 Knight, C. (1851). Cyclopaedia of London. p. 308. Retrieved 20 June 2013.

- ↑ Allen, Thomas (1839). The History and Antiquities of London, Westminster, Southwark, and Other Parts Adjacent. G. Virtue. p. 18. Retrieved 20 June 2013.

- ↑ http://www.ptomng.com/thesis/5katherine.pdf

- ↑ Arni, Eric Gruber Von (1 January 2006). Hospital Care and the British Standing Army: 1660 - 1714. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 109. ISBN 978-0-7546-5463-6. Retrieved 20 June 2013.

- ↑ Smith, Matthew (15 February 2011). Thomas Tooke and the Monetary Thought of Classical Economics. Taylor & Francis. p. 15. ISBN 978-1-136-81719-9. Retrieved 20 June 2013.

- ↑ Leech, Kenneth (2001). Through our long exile: contextual theology and the urban experience. Darton Longman & Todd. p. 212. Retrieved 20 June 2013.

- ↑ Plea Rolls of the Court of Common Pleas; National Archives; CP 40/541, in 1396; http://aalt.law.uh.edu/AALT6/R2/CP40no541a/aCP40no541afronts/IMG_0084.htm ; third entry, as plaintiff

- ↑ Besant, Sir Walter (1891). St. Katherine's by the tower: a novel. Chatto & Windus. Retrieved 20 June 2013.

- ↑ http://www.visionofbritain.org.uk/unit/10129680/cube/TOT_POP