Chad of Mercia

| Chad | |

|---|---|

| Bishop of York | |

Image of Chad in a stained glass window from Holy Cross Monastery, West Park, New York | |

| Appointed | 664 |

| Term ended | 669 |

| Predecessor | Paulinus |

| Successor | Wilfrid |

| Orders | |

| Consecration | 664 |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

c. 634 Northumbria |

| Died |

2 March 672 Lichfield, Staffordshire |

| Buried | Lichfield Cathedral |

| Sainthood | |

| Feast day | 2 March |

| Venerated in |

Catholic Church Anglican Communion Eastern Orthodox Church |

| Attributes | Bishop, holding a triple-spired cathedral (Lichfield) |

| Patronage | Mercia; Lichfield; of astronomers |

| Shrines |

|

Chad (Old English: Ceadda; died 2 March 672) was a prominent 7th century Anglo-Saxon churchman, who became abbot of several monasteries, Bishop of the Northumbrians and subsequently Bishop of the Mercians and Lindsey People. He was later canonised as a saint. He was the brother of Cedd, also a saint. He features strongly in the work of Bede the Venerable and is credited, together with Cedd, with introducing Christianity to the Mercian kingdom.

Sources

Most of our knowledge of Chad comes from the writings of Bede.[1] Bede tells us that he obtained his information about Chad and his brother, Cedd, from the monks of Lastingham,[2] where both were abbots. Bede gives this attribution great prominence, placing it in the introduction to his work. This may indicate that the brothers had become controversial figures: certainly Bede must have thought that his material about them would be of more than usual interest to the reader. Bede also refers to information he received from Trumbert, "who tutored me in the Scriptures and who had been educated in the monastery by that master",[3] i.e. Chad. In other words, Bede considered himself to stand in the spiritual lineage of Chad and had gathered information from at least one who knew him personally.

Early life and education

Family links

Chad was one of four brothers, all active in the Anglo-Saxon church. The others were Cedd, Cynibil and Caelin.[4] Chad seems to have been Cedd's junior, arriving on the political scene about ten years after Cedd. It is reasonable to suppose that Chad and his brothers were drawn from the Northumbrian nobility:[5] They certainly had close connections throughout the Northumbrian ruling class. However, the name Chad is actually of British Celtic, rather than Anglo-Saxon origin.[6] It is an element found in the personal names of many Welsh princes and nobles of the period and signifies "battle". This may indicate a family of mixed cultural and/or ethnic background, with roots in the original Celtic population of the region.

Education

The only major fact that Bede gives about Chad's early life is that he was a student of Aidan at the Celtic monastery at Lindisfarne.[7] In fact, Bede attributes the general pattern of Chad's ministry to the example of Aidan and his own brother, Cedd, who was also a student of St. Aidan.

Aidan was a disciple of Columba and was invited by the King Oswald of Northumbria to come from Iona to establish a monastery. Aidan arrived in Northumbria in 635 and died in 651. Chad must have studied at Lindisfarne some time between these years.

Travels in Ireland and dating of Chad's life

Chad later travelled to Ireland as a monk,[3] before he was ordained as a priest. Bede's references to this period are the only real evidence we have for dating the earlier part of Chad's life, including his birth.

Cedd is not mentioned as Chad's companion in this stage of his education. Probably Cedd was considerably older than Chad, and was ordained priest some years earlier: certainly he was already a priest by 653, when he was sent to work among the Middle Angles.[8] Chad's companion was Egbert, who was of about the same age as himself. The two travelled in Ireland for further study. Bede tells us that Egbert himself was of the Anglian nobility, although the monks sent to Ireland were of all classes. Bede places Egbert, and therefore Chad, among an influx of English scholars who arrived in Ireland while Finan and Colmán were bishops at Lindisfarne. This means that Egbert and Chad must have gone to Ireland later than the death of Aidan, in 651.

Bede gives a long account of how Egbert fell dangerously ill in Ireland in 664[9] and vowed to follow a lifelong pattern of great austerity so that he might live to make amends for the follies of his youth. His only remaining friend at this point was called Ethelhun, who died in the plague. Hence, Chad must have left Ireland before this. In fact, it is in 664 that he suddenly appears in Northumbria, to take over from his brother Cedd, also stricken by the plague. Chad's time in Ireland, therefore must fit into period 651–664. Bede makes clear that the wandering Anglian scholars were not yet priests, and ordination to the priesthood generally happened at the age of thirty – the age at which Jesus commenced his ministry. The year of Chad's birth is thus likely to be 634, or a little earlier, although certainty is impossible. Cynibil and Caelin were ordained priests by the late 650s, when they participated with Cedd in the founding of Lastingham. Chad was almost certainly the youngest of the four, probably by a considerable margin.

The Benedictine rule was slowly spreading across Western Europe, with encouragement from Rome. Chad was educated in an entirely distinct monastic tradition, indigenous to Western Europe itself, and tending to look back to the saint and monastic founder Martin of Tours as an exemplar,[10] although not as founder of an order. As Bede's account makes clear, the Irish and early Anglo-Saxon monasticism experienced by Chad was peripatetic, stressed ascetic practices and had a strong focus on Biblical exegesis, which generated a profound eschatological consciousness. Egbert recalled later that he and Chad "followed the monastic life together very strictly – in prayers and continence, and in meditation on Holy Scripture". Some of the scholars quickly settled in Irish monasteries, while others wandered from one master to another in search of knowledge. Bede says that the Irish monks gladly taught them and fed them, and even let them use their valuable books, without charge. Since books were all produced by hand, with painstaking attention to detail, this was astonishingly generous. The practice of loaning books freely seems to have been a distinctive feature of Irish monastic life: it was a violent dispute over rights to copies of a borrowed psalter which had allegedly led to Columba's exile from Ireland many years before.

Controversies

Struggle for political hegemony

Britain had no secure state structures even at a regional level. 7th-century rulers tried to build larger and more unified realms within defensible boundaries and to legitimise their power, under the prevailing culture. During Chad's lifetime the most important conflict was between Northumbria and Mercia. Penda, the pagan king of Mercia, continually campaigned against Northumbrian rulers, usually with the support of the Christian Welsh princes. Any defeat in this struggle tended to endanger the fragile unity of the defeated kingdom. In 641, Penda inflicted a crushing defeat on the Northumbrians, killing King Oswald. Northumbria broke into its component parts of Bernicia (north) and Deira, and its rival factions were easily manipulated by Penda. Northumbria was not fully reunited by Oswald's successor, Oswiu, until 651. Conversely, Oswiu defeated and killed Penda in 655, causing Mercia to descend into disunity for more than a decade, and allowing the Northumbrian rulers to intervene in Mercian affairs throughout that period.

Dispute over apostolic legitimacy in the Church

Christianity in the south of Britain was closely associated with Rome and with the Church in continental Europe. This was because its organisation had developed from the missions of Augustine of 597, sent by Pope Gregory I. However, the churches of Ireland and of western and northern Britain had their own distinct history and traditions. The churches of Wales and Cornwall had an unbroken tradition stretching back to Roman times. Ireland traced its Christian origins to missionaries from Wales, while Northumbria looked to the Irish monastery of Iona, in modern Scotland, as its source. Although all western Christians recognised Rome as the ultimate fount of authority, the semi-independent churches of Britain and Ireland did not accept actual Roman control. Considerable divergences had developed in practice and organisation. Most bishops in Ireland and Britain were not recognised by Rome because their apostolic succession was uncertain and they condoned non-Roman practices. Monastic practices and structures were very different: moreover monasteries played a much more important role in Britain and Ireland than on the continent, with abbots regarded as de facto leaders of the Church. Many of the differences related to disputes over the dating of Easter and the cut of the monastic tonsure, which were markedly and notoriously different in the local churches from those in Rome.

These political and religious issues were constantly intertwined, and interacted in various ways. Christianity in Britain and Ireland largely progressed through royal patronage, while kings increasingly used the Church to stabilise and to confer legitimacy on their fragile states. A strongly local church with distinctive practices could be a source of great support to a fledgling state, allowing the weaving together of political and religious elites. Conversely, the Roman connection introduced foreign influence beyond the control of local rulers, but also allowed rulers to display themselves on a wider, European stage, and to seek out more powerful sources of legitimacy.

These issues are also crucial in assessing the reliability of sources: Bede is the only substantial source for details of Chad's life. Bede wrote about sixty years after the crucial events of Chad's episcopate, when the Continental pattern of territorial bishoprics and Benedictine monasticism had become established throughout the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, including Northumbria. Bede was concerned to validate the Church practices and structures of his own time. However he also sought to present a flattering picture of the earlier Northumbrian church and monarchy: a difficult balancing act because, as Bede himself has constantly to acknowledge, the earlier institutions had resisted Roman norms for many decades.

Bede's treatment of Chad is particularly problematic because he could not conceal that Chad departed from Roman practices in vital ways – not only before the Synod of Whitby, which Bede presents as a total victory for the Roman party and its norms, but even after it. However, Chad was the teacher of Bede's own teacher, Trumbert, so Bede has an obvious personal interest in rehabilitating him, to say nothing of his loyalty to the Northumbrian establishment, which not only supported him but had played a notable part in Christianising England. This may explain a number of gaps in Bede's account of Chad, and why Bede sometimes seems to attribute to Chad implausible motives. Chad lived at and through a watershed in relations between the Anglo-Saxons and the wider Europe. Bede constantly tries to elide the ambiguities of Chad's career, not always successfully.

The rise of a dynasty

The course of Chad's life between his stay in Ireland and his emergence as a Church leader is unknown. In fact, it is possible that he had only recently returned from Ireland when prominence was thrust upon him. However, the growing importance of his family within the Northumbrian state is clear from Bede's account of Cedd's career of the founding of their monastery at Lastingham.[4] This concentration of ecclesiastical power and influence within the network of a noble family was probably common in Anglo-Saxon England: an obvious parallel would be the children of Merewalh in Mercia in the following generation.

The rise of Cedd

Cedd, probably the elder brother, had become a very prominent figure in the Church while Chad was in Ireland. Probably as a newly ordained priest, he was sent in 653 by Oswiu on a difficult mission to the Middle Angles, at the request of their sub-king Peada, part of a developing pattern of Northumbrian intervention in Mercian affairs. After perhaps a year, he was recalled and sent on a similar mission to the East Saxons, being ordained bishop shortly afterwards. Cedd's position as both a Christian missionary and a royal emissary compelled him to travel often between Essex and Northumbria.

The founding of Lastingham

Caelin, the brother of Cedd and Chad, was chaplain to Ethelwald, a nephew of Oswiu, who had been appointed to administer the coastal area of Deira. Caelin suggested to Ethelwald the foundation of a monastery, in which he could one day be buried, and where prayers for his soul would continue. Caelin introduced Ethelwold to Cedd, who needed just such a political base and spiritual retreat. Ethelwald, according to Bede, practically forced on Cedd a gift of land: a wild place at Lastingham, near Pickering in the North York Moors, close to one of the still-usable Roman roads. Bede explains that Cedd "fasted strictly in order to cleanse it from the filth of wickedness previously committed there". On the thirtieth day of his forty-day fast, he was called away on urgent business. Cynibil, another of his brothers, took over the fast for the remaining ten days.

The whole incident shows not only how closely the brothers were linked with Northumbria's ruling dynasty, but how close they were to each other. A fast by Cynibil was even felt to be equivalent to one by Cedd himself. Lastingham was handed over to Cedd, who became abbot. It was clearly conceived as a base for the family and destined to be under their control for the foreseeable future – not an unusual arrangement in this period.[11] Notably, however, Chad is not mentioned in this context until he succeeds his brother as abbot.

Chad as abbot of Lastingham

Chad's first appearance as an ecclesiastical prelate occurs in 664, shortly after the Synod of Whitby, when many Church leaders had been wiped out by the plague – among them Cedd, who died at Lastingham itself. On the death of his elder brother, Chad succeeded to the position of abbot at Lastingham.[4]

Bede seldom mentions Chad without referring to his regime of prayer and study, so these clearly made up the greater part of monastic routine at Lastingham. Study would have been collective, with monks carrying out exegesis through dialectic. Yet not all of the monks were intellectuals. Bede tells us of a man called Owin (Owen), who appeared at the door of Lastingham. Owin was a household official of Æthelthryth, an East Anglian princess who had come to marry Ecgfrith, Oswiu's younger son. He decided to renounce the world, and as a sign of this appeared at Lastingham in ragged clothes and carrying an axe. He had come primarily to work manually. He became one of Chad's closest associates.

Chad's eschatological consciousness and its effect on others is brought to life in a reminiscence attributed to Trumbert,[3] who was one of his students at Lastingham. Chad used to break off reading whenever a gale sprang up and call on God to have pity on humanity. If the storm intensified, he would shut his book altogether and prostrate himself in prayer. During prolonged storms or thunderstorms he would go into the church itself to pray and sing psalms until calm returned. His monks obviously regarded this as an extreme reaction even to English weather and asked him to explain. Chad explained that storms are sent by God to remind humans of the day of judgement and to humble their pride. The typically Celtic Christian involvement with nature was not like the modern romantic preoccupation but a determination to read in it the mind of God, particularly in relation to the last things.[12]

Bishop of the Northumbrians

The need for a bishop

Bede gives great prominence to the Synod of Whitby[13] in 663/4, which he shows resolving the main issues of practice in the Northumbrian Church in favour of Roman practice. Cedd is shown acting as the main go-between in the synod because of his facility with all of the relevant languages. Cedd was not the only prominent churchman to die of plague shortly after the synod. This was one of several outbreaks of the plague; they badly hit the ranks of the Church leadership, with most of the bishops in the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms dead, including the archbishop of Canterbury. Bede tells us that Colmán, the bishop of the Northumbrians at the time of the Synod, had left for Scotland after the Synod went against him. He was succeeded by Tuda, who lived only a short time after his accession. The tortuous process of replacing him is covered by Bede[7] briefly, but in some respects puzzlingly.

The mission of Wilfrid

The first choice to replace Tuda was Wilfrid, a particularly zealous partisan of the Roman cause. Because of the plague, there were not the requisite three bishops available to ordain him, so he had gone to the Frankish Kingdom of Neustria to seek ordination. This was on the initiative of Alfrid, sub-king of Deira, although presumably Oswiu knew and approved this action at the time. Bede tells us that Alfrid sought a bishop for himself and his own people. This probably means the people of Deira. According to Bede, Tuda had been succeeded as abbot of Lindisfarne by Eata, who had been elevated to the rank of bishop.

Wilfrid met with his own teacher and patron, Agilbert, a spokesman for the Roman side at Whitby, who had been made bishop of Paris. Agilbert set in motion the process of ordaining Wilfrid canonically, summoning several bishops to Compiègne for the ceremony. Bede tells us that he then lingered abroad for some time after his ordination.

The elevation of Chad

Bede implies that Oswiu decided to take further action because Wilfrid was away for longer than expected. It is unclear whether Oswiu changed his mind about Wilfrid, or whether he despaired of his return, or whether he never really intended him to become bishop but used this opportunity to get him out of the country.

Chad was invited then to become bishop of the Northumbrians by King Oswiu. Chad is often listed as a Bishop of York. Bede generally uses ethnic, not geographical, designations for Chad and other early Anglo-Saxon bishops. However at this point, he does also refer to Oswiu's desire that Chad become bishop of the church in York. York later became the diocesan city partly because it had already been designated as such in the earlier Roman-sponsored mission of Paulinus to Deira, so it is not clear whether Bede is simply echoing the practice of his own day, or whether Oswiu and Chad were considering a territorial basis and a see for his episcopate. It is quite clear that Oswiu intended Chad to be bishop over the entire Northumbrian people, over-riding the claims of both Wilfrid and Eata.

Chad faced the same problem over ordination as Wilfrid, and so set off to seek ordination amid the chaos caused by the plague. Bede tells us that he travelled first to Canterbury, where he found that Archbishop Deusdedit was dead and his replacement was still awaited. Bede does not tell us why Chad diverted to Canterbury. The journey seems pointless, since the archbishop had died three years previously – a fact that must have been well known in Northumbria, and was the very reason Wilfrid had to go abroad. The most obvious reason for Chad's tortuous travels would be that he was also on a diplomatic mission from Oswiu, seeking to build an encircling alliance around Mercia, which was rapidly recovering from its position of weakness. From Canterbury he travelled to Wessex, where he was ordained by bishop Wini of the West Saxons and two British, i.e. Welsh, bishops. None of these bishops was recognised by Rome. Bede points out that "at that time there was no other bishop in all Britain canonically ordained except Wini" and the latter had been installed irregularly by the king of the West Saxons.

Bede describes Chad at this point as "a diligent performer in deed of what he had learnt in the Scriptures should be done." Bede also tells us that Chad was teaching the values of Aidan and Cedd. His life was one of constant travel. Bede says that Chad visited continually the towns, countryside, cottages, villages and houses to preach the Gospel. Clearly, the model he followed was one of the bishop as prophet or missionary. Basic Christian rites of passage, baptism and confirmation, were almost always performed by a bishop, and for decades to come they were generally carried out in mass ceremonies, probably with little systematic instruction or counselling.

The removal of Chad

In 666, Wilfrid returned from Neustria, "bringing many rules of Catholic observance", as Bede says. He found Chad already occupying the same position. It seems that he did not in fact challenge Chad's pre-eminence in his own area. Rather, he would have worked assiduously to build up his own support in sympathetic monasteries, like Gilling and Ripon. He did, however, assert his episcopal rank by going into Mercia and even Kent to ordain priests. Bede tells us that the net effect of his efforts on the Church was that the Irish monks who still lived in Northumbria either came fully into line with Catholic practices or left for home. Nevertheless, Bede cannot conceal that Oswiu and Chad had broken significantly with Roman practice in many ways and that the Church in Northumbria had been divided by the ordination of rival bishops.

In 669, a new Archbishop of Canterbury, Theodore of Tarsus, sent by Pope Vitalian arrived in England. He immediately set off on a tour of the country, tackling abuses of which he had been forewarned. He instructed Chad to step down and Wilfrid to take over.[14] According to Bede, Theodore was so impressed by Chad's show of humility that he confirmed his ordination as bishop, while insisting he step down from his position. Chad retired gracefully and returned to his post as abbot of Lastingham, leaving Wilfrid as bishop of the Northumbrians at York.[3]

Bishop of the Mercians

The recall of Chad

Later that same year, King Wulfhere of Mercia requested a bishop. Wulfhere and the other sons of Penda had converted to Christianity, although Penda himself had remained a pagan until his death (655). Penda had allowed bishops to operate in Mercia, although none had succeeded in establishing the Church securely without active royal support.

Archbishop Theodore refused to consecrate a new bishop. Instead he recalled Chad out of his retirement at Lastingham. According to Bede, Theodore was greatly impressed by Chad's humility and holiness. This was displayed particularly in his refusal to use a horse: he insisted on walking everywhere. Despite his regard for Chad, Theodore ordered him to ride on long journeys and went so far as to lift him into the saddle on one occasion.

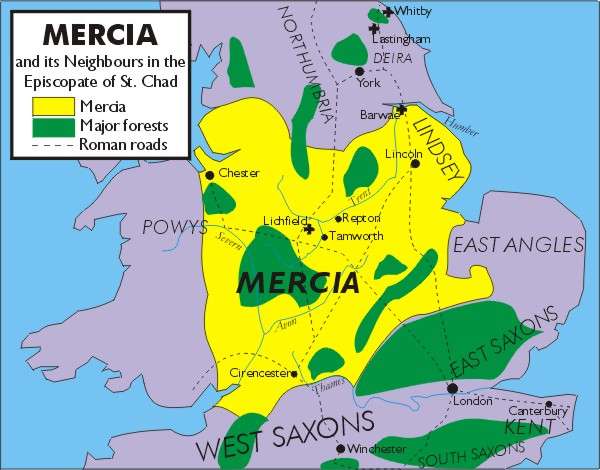

Chad was consecrated bishop of the Mercians (literally, frontier people) and of the Lindsey people (Lindisfaras). Bede tells us that Chad was actually the third bishop sent to Wulfhere, making him the fifth bishop of the Mercians.[15] The Kingdom of Lindsey, covering the north-eastern area of modern Lincolnshire, was under Mercian control, although it had in the past sometimes fallen under Northumbrian control. Later Anglo-Saxon episcopal lists sometimes add the Middle Angles to his responsibilities.[16] They were a distinct part of the Mercian kingdom, centred on the middle Trent and lower Tame – the area around Tamworth, Lichfield and Repton that formed the core of the wider Mercian polity. It was their sub-king, Peada, who had secured the services of Chad's brother Cedd in 653, and they were frequently considered separately from the Mercians proper, a people who lived further to the west and north.

Monastic foundations

Wulfhere donated land at Lichfield for Chad to build a monastery. It was because of this that the centre of the Diocese of Mercia ultimately became settled at Lichfield.[3] The Lichfield monastery was probably similar to that at Lastingham, and Bede makes clear that it was partly staffed by monks from Lastingham, including Chad's faithful retainer, Owin. Lichfield was very close to the old Roman road of Watling Street, the main route across Mercia, and a short distance from Mercia's main royal centre at Tamworth.

Wulhere also donated land sufficient for fifty families at a place in Lindsey, referred to by Bede as Ad Barwae. This is probably Barrow upon Humber: where an Anglo-Saxon monastery of a later date has been excavated. This was easily reached by river from the Midlands and close to an easy crossing of the River Humber, allowing rapid communication along surviving Roman roads with Lastingham. Chad remained abbot of Lastingham throughout his life, as well as heading the communities at both Lichfield and Barrow.

Chad's ministry among the Mercians

Chad then proceeded to carry out much missionary and pastoral work within the kingdom. Bede tells us that Chad governed the bishopric of the Mercians and of the people of Lindsey 'in the manner of the ancient fathers and in great perfection of life'. However, Bede gives little concrete information about the work of Chad in Mercia, implying that in style and substance it was a continuation of what he had done in Northumbria. The area he covered was very large, stretching across England from coast to coast. It was also, in many places, difficult terrain, with woodland, heath and mountain over much of the centre and large areas of marshland to the east. Bede does tell us that Chad built for himself a small house at Lichfield, a short distance from the church, sufficient to hold his core of seven or eight disciples, who gathered to pray and study with him there when he was not out on business.

Chad worked in Mercia and Lindsey for only two and a half years before he too died during a plague. Yet St. Bede could write in a letter that Mercia came to the faith and Essex was recovered for it by the two brothers Cedd and Chad. In other words, Bede considered that Chad's two years as bishop were decisive in Christianising Mercia.

The death of Chad

Chad died on 2 March 672, and was buried at the Church of Saint Mary which later became part of the cathedral at Lichfield. Bede relates the death story as that of a man who was already regarded as a saint. In fact, Bede has stressed throughout his narrative that Chad's holiness communicated across boundaries of culture and politics, to Theodore, for example, in his own lifetime. The death story is clearly of supreme importance to Bede, confirming Chad's holiness and vindicating his life. The account occupies considerably more space in Bede's account than all the rest of Chad's ministry in Northumbria and Mercia together.

Bede tells us that Owin was working outside the oratory at Lichfield. Inside, Chad studied alone because the other monks were at worship in the church. Suddenly Owin heard the sound of joyful singing, coming from heaven, at first to the south-east, but gradually coming closer until it filled the roof of the oratory itself. Then there was silence for half an hour, followed by the same singing going back the way it had come. Owin at first did nothing, but about an hour later Chad called him in and told him to fetch the seven brothers from the church. Chad gave his final address to the brothers, urging them to keep the monastic discipline they had learnt. Only after this did he tell them that he knew his own death was near, speaking of death as "that friendly guest who is used to visiting the brethren". He asked them to pray, then blessed and dismissed them. The brothers left, sad and downcast.

Owin returned a little later and saw Chad privately. He asked about the singing. Chad told him that he must keep it to himself for the time being: angels had come to call him to his heavenly reward, and in seven days they would return to fetch him. So it was that Chad weakened and died after seven days – on 2 March, which remains his feast day. Bede writes that: "he had always looked forward to this day – or rather his mind had always been on the Day of the Lord". Many years later, his old friend Egbert told a visitor that someone in Ireland had seen the heavenly company coming for Chad's soul and returning with it to heaven. Significantly, with the heavenly host was Cedd. Bede was not sure whether or not the vision was actually Egbert's own.

Bede's account of Chad's death strongly confirms the main themes of his life. Primarily he was a monastic leader, deeply involved in the fairly small communities of loyal monks who formed his mission teams, his brothers. His consciousness was strongly eschatological: focussed on the last things and their significance. Finally, he was inextricably linked with Cedd and his other actual brothers.

Cult and Relics

Chad is considered a saint in the Roman Catholic,[17] the Anglican churches, the Celtic Orthodox Church and is also noted as a saint in a new edition of the Eastern Orthodox Synaxarion (Book of Saints). His feast day is celebrated on 2 March.[17]

According to St. Bede, Chad was venerated as a saint immediately after his death, and his relics were translated to a new shrine. He remained the centre of an important cult, focussed on healing, throughout the Middle Ages. The cult had twin foci: his tomb, in the apse, directly behind the high altar of the cathedral; and more particularly his skull, kept in a special Head Chapel, above the south aisle.

The transmission of the relics after the Reformation was tortuous. At the dissolution of the Shrine on the instructions of King Henry VIII in about 1538, Prebendary Arthur Dudley of Lichfield Cathedral removed and retained some relics, probably a travelling set. These were eventually passed to his nieces, Bridget and Katherine Dudley, of Russells Hall. In 1651, they reappeared when a farmer Henry Hodgetts of Sedgley was on his death-bed and kept praying to St Chad. When the priest hearing his last confession, Fr Peter Turner SJ, asked him why he called upon Chad. Henry replied, "because his bones are in the head of my bed". He instructed his wife to give the relics to the priest, whence they found their way to the Seminary at St Omer, in France. After the conclusion of penal times, in the early 19th century, they found their way into the hands of Sir Thomas Fitzherbert-Brockholes of Aston Hall, near Stone, Staffordshire. When his chapel was cleared after his death, his chaplain, Fr Benjamin Hulme, discovered the box containing the relics, which were examined and presented to Bishop Thomas Walsh, the Roman Catholic Vicar Apostolic of the Midland District in 1837 and were enshrined in the new St Chad's Cathedral, Birmingham, opened in 1841, in a new ark designed by Augustus Pugin.

The relics, some long bones, are now enshrined on the Altar of St Chad's Cathedral. They were examined by the Oxford Archeological Laboratory by carbon dating techniques in 1985, and all but one of the bones (which was a third femur, and therefore could not have come from Bishop Chad) were dated to the seventh century, and were authenticated as 'true relics' by the Vatican authorities. In 1919, an Annual Mass and Solemn Outdoor Procession of the Relics was held at St Chad's Cathedral in Birmingham. This observance continues to the present, on the Saturday nearest to his Feast Day, 2 March.

Portrayals of St Chad

There are no portraits or descriptions of St Chad from his own time. The only hint that we have comes in the legend of Theodore lifting him bodily into the saddle – possibly suggesting that he was remembered as small in stature. All attempts to portray him are based entirely on imagination, and nearly all are obviously anachronistic, with a heavy stress on vestments from other periods.

-

St Chad, Peada and Wulfhere, as portrayed in 19th century sculpture above the western entrance to Lichfield Cathedral.

-

Icon used devotionally at the site of the shrine of St Chad in Lichfield Cathedral.

-

"Saint Chad", stained glass window by Christopher Whall. Currently exhibited at Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

-

_-_geograph.org.uk_-_1592962.jpg)

An example of a late sculpture of St. Chad, from St. Chad's Church, Lichfield, Staffordshire, 1930.

Notable dedications

Churches

Chad gives his name to Birmingham's Roman Catholic cathedral, where there are some relics of the saint: about eight long bones. It is the only cathedral in England that has the relics of its patron saint enshrined upon its high altar. The Anglican Lichfield Cathedral, at the site of his burial, is dedicated to Chad, and St Mary, and still has a head chapel, where the skull of the saint was kept until it was lost during the Reformation. The site of the medieval shrine is also marked.

Chad also gives his name to a parish church in Lichfield (with Chad's Well, where traditionally Chad baptised converts: now a listed building).

Dedications are densely concentrated in the West Midlands. The city of Wolverhampton, for example, has two Anglican churches and a Roman Catholic secondary school dedicated to Chad, while the nearby village of Pattingham has both an Anglican church and primary school. Shrewsbury had a large medieval church of St Chad which fell down in 1788: it was quickly replaced by a circular church in Classical style by George Steuart, on a different site but with the same dedication. Parish Church in Montford, built in 1735-38, site of the graves of the parents of Charles Darwin.[18] Parish Church in Coseley built in 1882. Further afield, there is a considerable number of dedications in areas associated with Chad's career, like the churches in Church Wilne in Derbyshire and Far Headingley in Leeds and the Parish Church of Rochdale, Greater Manchester, as well as some in the Commonwealth, like Chelsea in Australia. There is also a St Chad's College within the University of Durham, founded in 1904 as an Anglican hall.

Toponyms

There are many place names containing the element chad or something similar. In many cases, reference to the early forms of the name suggests that the derivation is not from the name Chad, but from some other word. It is possible that even where a name might reasonably be thought to derive from Chad that the individual is some other of the same name. Hence great caution needs to be exercised in explaining ancient toponyms by reference to St Chad.

One toponym with a good claim to derivation from the saint's name is Chadkirk Chapel in Romiley, Greater Manchester, which dates back to the 14th century – although the site is much older, possibly dating back to the 7th century when it is believed St Chad visited to bless the well there. Cameron[19] points out that -kirk toponyms more frequently incorporate the name of the dedicatee, rather than the patron, so there is every reason to believe that Chadkirk really was dedicated to St Chad in the Middle Ages. It is not so certain that Chadsmoor in Staffordshire, Chadwich in Worcestershire, or Chadwick in Warwickshire, were named after the saint.

St Chad's Well[20] near Battle Bridge on the river Fleet in London was a celebrated medicinal well and had a new pump house built in 1832.[21] It was destroyed by the Midland Railway company, and is remembered in the street name of St Chad's Place. There is no independent evidence of Chad's visiting the site, but it clearly is named after him, and he certainly did travel in southern England. His association with wells seems ancient, and no doubt stems from the St Chad's Well at Lichfield, visited by pilgrims and probably the water supply of his monastery. This is the most likely explanation of the name.

Numerous place-names like Cheadle and Cheddleton, in the Midlands suggest a link with Chad. However "suggestions" based on late forms of the name count for little: a hypothesis should be framed instead from documentary and topographical evidence. Mostly names of this sort are derived from other Celtic roots, generally ced, cognate with modern Welsh coed, signifying a wood or heath. Cheadle, for example, is generally reckoned a tautonym,[22] with the Old English leah, also meaning a wood, glossing the original Celtic term.[23] This means that the origins of its name are closely related to those of Lichfield (originally derived from the Celtic for "grey wood"), to which it bears little superficial resemblance, rather than Chad or even his brother, Cedd.

There is a village in Northamptonshire called Chadstone, after which the (rather larger) suburb of Chadstone in Melbourne Australia is named.

Kidderminster, in Worcestershire, is sometimes said to be a corruption of the name of 'St Chad's Minster'. However, place-names do not "corrupt" randomly, but evolve according to principles inherent in the history of the language. Chad or Ceadda would not normally evolve into Kidder. The existence of a minster dedicated to Chad in this town seems to be a legend traceable to Burton's 1890 History of Kidderminster,[24] in which the author acknowledges that the only evidence for such a place is the name of the town. Later writers seem to assume the existence of the monastery and then explain the name of the town from it – a circular argument that collapses if a plausible alternative explanation is available for the name. A grant of land by Æthelbald of Mercia in 736[16] to one Cyneberht[25] is generally accepted as the origin of the settlement. Cameron suggests that the minster was named after a lay benefactor (normal with -minster formations) and hypothesises Cydela,[26] a suggestion that has found general acceptance.[27] Another possibility might be the later Mercian dux Cydda.[25] Certainly it seems that there was a dynasty of Mercian noblemen, all with similar names beginning Cy and connected to the area. These provide a more plausible explanation for the name of the town than St Chad or his non-existent minster.

The settlement of St Chad's (population 57) in Newfoundland was previously named "St Shad's" (after originally being "Damnable"),but was renamed after postal confusion with nearby "St Shott's" .

Chad as a personal name

Chad remains a fairly popular given name, one of the few personal names current among 7th century Anglo-Saxons to do so. However, it was very little used for many centuries before a modest revival in the mid-20th century. Not all of its bearers are named directly after Chad of Mercia. Perhaps the best-known Chad of modern times who was so-named was Chad Varah, an Anglican priest and social activist, whose father was vicar of Barton-upon-Humber – the probable site of Chad's monastery in the north of Lindsey.

Patronage

Due to the somewhat confused nature of Chad's appointment and the continued references to 'chads' – small pieces of ballot papers punched out by voters using voting machines – in the 2000 US Presidential Election it has been jocularly suggested that Chad is the patron saint of botched elections. In fact there is no official patron saint of elections, though Thomas More is the one of politicians.

The Spa Research Fellowship states that Chad is the patron saint of medicinal springs,[28] although other listings (e.g. ) do not mention this patronage.

St. Chad's Day (2 March) is traditionally considered the most propitious day to sow broad beans in England.

See also

![]() Media related to Chad of Mercia at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Chad of Mercia at Wikimedia Commons

References

- ↑ Leo Sherley-Price (1990). Ecclesiastical History of the English People by Bede. Penguin Classics. ISBN 0-14-044565-X.

- ↑ Bede. Ecclesiastical History of the English People, Preface.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Bede. Ecclesiastical History of the English People, Book 4, chapter 3.

- 1 2 3 Bede. Ecclesiastical History of the English People, Book 3, chapter 23.

- ↑ Richard Fletcher (1997). The Conversion of Europe, p.167. HarperCollins. ISBN 0-00-255203-5.

- ↑ Koch, J.T., (2006) Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia, ABC-CLIO, ISBN 1-85109-440-7, p. 360

- 1 2 Bede. Ecclesiastical History of the English People, Book 3, chapter 28.

- ↑ Bede. Ecclesiastical History of the English People, Book 3, chapter 21.

- ↑ Bede. Ecclesiastical History of the English People, Book 3, chapter 27.

- ↑ Mayr-Harting, Henry. The Coming of Christianity to Anglo-Saxon England. 1991. Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 978-0-271-00769-4. p. 97.

- ↑ Mayr-Harting, Henry. The Coming of Christianity to Anglo-Saxon England. 1991. Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 978-0-271-00769-4. P. 253.

- ↑ Mayr-Harting, Henry. The Coming of Christianity to Anglo-Saxon England. 1991. Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 978-0-271-00769-4. p. 89.

- ↑ Bede. Ecclesiastical History of the English People, Book 3, chapter 25.

- ↑ Bede. Ecclesiastical History of the English People, Book 4, chapter 2.

- ↑ Bede. Ecclesiastical History of the English People, Book 3, chapter 24.

- 1 2 "Chad 1". Prosopography of Anglo-Saxon England. Retrieved June 2009.

- 1 2 Farmer, David Hugh (2004). Oxford Dictionary of Saints (Fifth ed.). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. pp. 101–102. ISBN 978-0-19-860949-0.

- ↑ "Church of Saint Chad, Montford" Source: British Listed Buildings, accessed 7 April 2015

- ↑ Cameron, Kenneth: English Place Names, London: Batsford, 1996, ISBN 0-7134-7378-9, p.127.

- ↑ Potter, Cesca River of wells Source: the holy wells journal, series 1, issue 1

- ↑ The London Encyclopaedia p. 699

- ↑ Ayto, John and Croft, Ian: Brewer's Britain and Ireland, London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 2005, ISBN 0-304-35385-X, p. 225.

- ↑ Gelling, Margaret: Place-Names in the Landscape, London: Dent, 1984, ISBN 0-460-86086-0, pp. 190–191.

- ↑ Burton, John Richard: A History of Kidderminster, London: Elliot Stock, 1890, p. 14.

- 1 2 "Cyneberht 3". Prosopography of Anglo-Saxon England. Retrieved June 2009.

- ↑ Cameron, Kenneth: English Place Names, London: Batsford, 1996, ISBN 0-7134-7378-9, p. 126.

- ↑ Ayto, John and Croft, Ian: Brewer's Britain and Ireland, London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 2005, ISBN 0-304-35385-X, p. 608.

- ↑ Spa research fellowship, Occasional paper, 5: St Chad – Patron Saint of Medicinal Springs

Background reading

- Bassett, Steven, Ed. The Origins of the Anglo-Saxon Kingdoms. Leicester University Press, 1989. ISBN 978-0-7185-1367-2.

- Fletcher, Richard. The Conversion of Europe: From Paganism to Christianity 371–1386. HarperCollins, 1997. ISBN 0-00-255203-5.

- Mayr-Harting, Henry. The Coming of Christianity to Anglo-Saxon England. 1991. Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 978-0-271-00769-4..

- Rudolf Vleeskruijer The Life of St.Chad, an Old English Homily edited with introduction, notes, illustrative texts and glossary by R. Vleeskruyer, North-Holland, Amsterdam (1953)

External links

| Catholic Church titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Jaruman as Bishop of Mercia |

Bishop of the Mercians and Lindsey People 669–672 |

Succeeded by Winfrith as Bishop of Lichfield |

| Vacant Title last held by Paulinusas Bishop of York |

Bishop of the Northumbrians 664–669 |

Succeeded by Wilfrid |

| Preceded by Tuda as Bishop of Lindisfarne | ||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|