St. Bride's Church, Dublin

Coordinates: 53°20′22″N 6°16′17″W / 53.33944°N 6.27139°W St. Bride's Church is a former Church of Ireland church located in Bride St., Dublin, Ireland.

The church

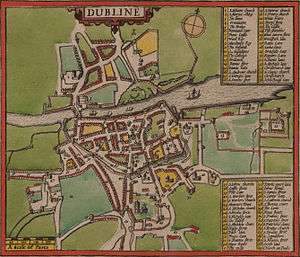

The original St. Bride's church was an ancient Irish church located south of the walls of Dublin, dating back to pre-Viking times, and dedicated to St. Bridget (Irish: Naomh Bríd).[1] It was located north-east of where St. Patrick's Cathedral now stands.[2] By a grant of St. Laurence O'Toole in 1178, its revenues were appropriated to the Priory of the Holy Trinity (Christ Church Cathedral), but his was later transferred to the Economy Fund of St. Patrick's Cathedral. Until the Reformation its history was devoid of incident.[3]

The church (now belonging to the Church of Ireland) was rebuilt in 1684 by Nathaniel Foy, rector of St. Bride's, born in York but educated in Dublin. He later became Bishop of Waterford where he founded Bishop Foy's School.

St. Bride's was closed in 1898, but its fine organ-case can still be seen in the National Museum of Ireland. It was demolished to make way for the housing development for the poor, the Iveagh Trust, financed by Edward Guinness, 1st Earl of Iveagh, which still stands on the spot.

The churchyard

A large number of parishioners were buried in the churchyard, some of whose remains were transferred to Mount Jerome Cemetery when the land was developed at the turn of the 20th century.

Thomas Carter (1690–1763), politician and Master of the Rolls in Ireland, was buried in the church.

O'Hanlon, keeper of the Record Tower in Dublin Castle, who was killed by Howley, one of the insurgents during the rebellion of Robert Emmet in 1803, is buried here.[2]

The developer and philanthropist Thomas Pleasants (1729–1818, after whom Pleasants Street was named) and his wife Mildred Daunt (died 1814) were buried in the churchyard. Among his donations were over £12,000 in 1814 for the erection of a large stove-house near Cork St. for poor weavers in the Liberties, £8,000 for the building of the Meath Hospital, and his own house (67 Camden St.) for the provision of a school and orphanage for Protestant girls, along with £1,200 a per annum operational grant and funding for modest dowries for the girls.[4]

The parish

This parish (which was also known as St. Bridget's) consisted of a union of three smaller parishes: the ancient St. Bride's, St. Stephen's (which dated from the 13th century), and St. Michael de la Pole (also an Irish pre-Norse settlement).

In 1707 parts of the parish were taken, along with parts of the parishes of St. Peter and St. Kevin, to form the new parish of St. Anne. The parish extended along Bride St. as far as Ship St. (the location of the church of St. Michael de la Pole) on one end and Golden Lane at the other, and eastwards as far as George's St. and Stephen St. (location of the original St. Stephen's church). The parish corresponded to the civil parish of St. Bridget.[2] In 1766, the government ordered a religious census to be carried out by the Protestant clergy, which showed the parish had 430 Catholic families and 84 Protestant families.[5]

Owing to an influx of civil servants and its central location close to the centre of power at Dublin Castle the parish initially did have some wealthy parishioners. However, a number of economic slumps affecting workers in the Liberties during the 18th century meant that by the 19th century the parish was one of the poorest in the city, containing many tenements which were unhygienic slums. In 1813 the parish population was 4,367 males and 5,272 females,[6] of whom only a small minority were members of the Established (Church of Ireland) Church. The population continued to increase, especially during and after the Famine, when this part of Dublin was flooded with poverty-stricken country people looking for work and lodgings.

During a bad economic downturn in 1863 the Carmelite priest Father Spratt, from nearby Whitefriar St. Church, conducted house-to-house collections throughout the city to raise funds for the most destitute in the parish, which numbered 6,000.[7] The then rector of St. Bride's, Rev. William Carroll, also spent much of his time caring for the poor of the parish, both Catholic and Protestant - he was known as "Father" Carroll by the Catholics of the neighbourhood.

In 1901 the population of the parish was 6,155 and in 1971, after many of the older houses in the neighbourhood had been demolished, it was 1,335.[8]

Notable parishioners

Sir William Petty (1623–1687) while in Dublin was a pew-holder, vault-owner and prominent member of the parish. He lived firstly in Exchequer St., then on the north side of St. Stephen's Green, where the Shelbourne Hotel now stands.[9]\

Sir Edward Bolton, Chief Baron of the Irish Exchequer, was buried here in 1659.[10]

The writer and politician Sir Richard Steele was christened in St. Bride's parish Church on 12 March 1672.[11]

Arthur Keene (died 1818), a prominent member of the Methodist community in Dublin in its early days, was married to his wife Isabella by John Wesley in this church in April 1775.[12]

Many members of the Lloyd family of New Ross, two of whom (Bartholomew Lloyd (1772–1837) and his son Humphrey Lloyd) were provosts of Trinity College, Dublin, were baptized, married or buried in this church. These included Dr Thomas Lloyd (baptized 1756), Christopher Lloyd, Dean of Elphin (buried 1787) and Alderman Edward Lloyd, Lord Mayor.[13]

The Rev. Peter Le Fanu (1749–1825), a relative of Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu became curate in this parish in the 1770s. He became known as one of the most popular preachers in Dublin and was also a playwright.[14]

Several members of the Domville family were parishioners: perhaps the most eminent of them, Sir William Domville, the father-in-law of William Molyneux, and for many years Attorney General for Ireland , wrote A Disquisition Touching That Great Question Whether an Act of Parliament Made in England Shall Bind the Kingdom and People of Ireland Without Their Allowance and Acceptance of Such Act in the Kingdom of Ireland, which influenced Molyneux.[15] William was the son of Gilbert Domville (1565–1624), who came to Ireland from Cheshire during the reign of James I.[16]

A highly regarded rector of St. Bride's in the second half of the 19th century was the Rev. William George Carroll (1821–1885), historian and writer. He was an uncle of George Bernard Shaw and was the first Protestant clergyman in Ireland to declare for Home Rule.[17] He collected a large amount of information regarding his church and parish, discovering a mine of wealth in the old registers, dating back to 1633. It is considered one of the most valuable parochial collections in Ireland.[18]

See also

Further reading

William George Carroll and William Reeves: Succession of Clergy in the Parishes of S. Bride, S. Michael le Pole, and S. Stephen, Dublin (Dublin, 1884)

References and sources

- Notes

- ↑ Craig, p. 40

- 1 2 3 Wright, 1825

- ↑ Donnelly (1916), p. 10

- ↑ O'Donovan, 1986, p. 53

- ↑ N. Donnelly: A Short History of Dublin Parishes. Dublin, 1916. Part VI, pp. 52-55

- ↑ Government figures quoted in M'Gregor, Picture of Dublin (1821), p. 62

- ↑ Report (29 May 1863), "St. Bride's Parish", The Irish Times, p. 4

- ↑ CSO Ireland, 1971 Census

- ↑ Parish records

- ↑ Ball, F. Elrington The Judges in Ireland 1221-1921 John Murray London 1926

- ↑ Biography

- ↑ Proceedings of the Wesley Historical Society, 1906, Vol. V, p. 74

- ↑ Carroll, 1875

- ↑ Taylor, 1845

- ↑ Patrick Kelly. 'Sir William Domville, A Disquisition Touching That Great Question...', Analecta Hibernica, no. 40 (2007): 19-69.

- ↑ Dalton, 1838

- ↑ Bernard Shaw by Holbrook Jackson. London, Jacob's and Co. 1907. p. 37

- ↑ P. J. McCall. In the Shadow of St. Patrick's (a paper read before the Irish National Literary Society, April 27, 1893)

- Sources

- Gilbert, John (1854). A History of the City of Dublin. Oxford: Oxford University.

- O'Donovan, John (1986). Life by the Liffey. Dublin: Gill and Macmillan.

- George Newenham Wright (2005). "An Historical Guide to the City of Dublin (1825)". Online book. Retrieved 2008-11-02.

- Craig, Maurice (1969). Dublin: 1660-1860. Dublin: Allen Figgis.

- Ryan, James G. (2001). Irish Church Records. Flyleaf Press. ISBN 0-9539974-0-5.

- Taylor, W. B. S. (1845). A History of the University of Dublin. Dublin: J. Gumming.

- Carroll, William George (1875). A Memoir of the Right Rev James O'Brien. Dublin: Robertson & Co. ISBN 978-1-110-23354-0.

- D'Alton, John (1838). History of the County of Dublin. Dublin: Hodges and Smith.

- Donnelly, N (1916). A Short History of Dublin Parishes. Dublin.