Spin–statistics theorem

| Statistical mechanics |

|---|

|

|

In quantum mechanics, the spin–statistics theorem relates the spin of a particle to the particle statistics it obeys. The spin of a particle is its intrinsic angular momentum (that is, the contribution to the total angular momentum that is not due to the orbital motion of the particle). All particles have either integer spin or half-integer spin (in units of the reduced Planck constant ħ).[1][2]

The theorem states that:

- The wave function of a system of identical integer-spin particles has the same value when the positions of any two particles are swapped. Particles with wave functions symmetric under exchange are called bosons.

- The wave function of a system of identical half-integer spin particles changes sign when two particles are swapped. Particles with wave functions antisymmetric under exchange are called fermions.

In other words, the spin–statistics theorem states that integer-spin particles are bosons, while half-integer–spin particles are fermions.

The spin–statistics relation was first formulated in 1939 by Markus Fierz[3] and was rederived in a more systematic way by Wolfgang Pauli.[4] Fierz and Pauli argued their result by enumerating all free field theories subject to the requirement that there be quadratic forms for locally commuting observables including a positive-definite energy density. A more conceptual argument was provided by Julian Schwinger in 1950. Richard Feynman gave a demonstration by demanding unitarity for scattering as an external potential is varied,[5] which when translated to field language is a condition on the quadratic operator that couples to the potential.[6]

General discussion

In a given system, two indistinguishable particles, occupying two separate points, have only one state, not two. This means that if we exchange the positions of the particles, we do not get a new state, but rather the same physical state. In fact, one cannot tell which particle is in which position.

A physical state is described by a wavefunction, or – more generally – by a vector, which is also called a "state"; if interactions with other particles are ignored, then two different wavefunctions are physically equivalent if their absolute value is equal. So, while the physical state does not change under the exchange of the particles' positions, the wavefunction may get a minus sign.

Bosons are particles whose wavefunction is symmetric under such an exchange, so if we swap the particles the wavefunction does not change. Fermions are particles whose wavefunction is antisymmetric, so under such a swap the wavefunction gets a minus sign, meaning that the amplitude for two identical fermions to occupy the same state must be zero. This is the Pauli exclusion principle: two identical fermions cannot occupy the same state. This rule does not hold for bosons.

In quantum field theory, a state or a wavefunction is described by field operators operating on some basic state called the vacuum. In order for the operators to project out the symmetric or antisymmetric component of the creating wavefunction, they must have the appropriate commutation law. The operator

(with  an operator and

an operator and  a numerical function)

creates a two-particle state with wavefunction

a numerical function)

creates a two-particle state with wavefunction  , and depending on the commutation properties of the fields, either only the antisymmetric parts or the symmetric parts matter.

, and depending on the commutation properties of the fields, either only the antisymmetric parts or the symmetric parts matter.

Let us assume that  and the two operators take place at the same time; more generally, they may have spacelike separation, as is explained hereafter.

and the two operators take place at the same time; more generally, they may have spacelike separation, as is explained hereafter.

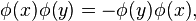

If the fields commute, meaning that the following holds:

,

,

then only the symmetric part of  contributes, so that

contributes, so that  , and the field will create bosonic particles.

, and the field will create bosonic particles.

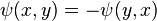

On the other hand, if the fields anti-commute, meaning that  has the property that

has the property that

then only the antisymmetric part of  contributes, so that

contributes, so that  , and the particles will be fermionic.

, and the particles will be fermionic.

Naively, neither has anything to do with the spin, which determines the rotation properties of the particles, not the exchange properties.

A suggestive bogus argument

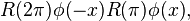

Consider the two-field operator product

where R is the matrix that rotates the spin polarization of the field by 180 degrees when one does a 180-degree rotation around some particular axis. The components of  are not shown in this notation,

are not shown in this notation,  has many components, and the matrix R mixes them up with one another.

has many components, and the matrix R mixes them up with one another.

In a non-relativistic theory, this product can be interpreted as annihilating two particles at positions  and

and  with polarizations that are rotated by

with polarizations that are rotated by  relative to each other. Now rotate this configuration by

relative to each other. Now rotate this configuration by  around the origin. Under this rotation, the two points

around the origin. Under this rotation, the two points  and

and  switch places, and the two field polarizations are additionally rotated by a

switch places, and the two field polarizations are additionally rotated by a  . So we get

. So we get

which for integer spin is equal to

and for half-integer spin is equal to

(proved here). Both the operators  still annihilate two particles at

still annihilate two particles at  and

and  . Hence we claim to have shown that, with respect to particle states:

. Hence we claim to have shown that, with respect to particle states:

So exchanging the order of two appropriately polarized operator insertions into the vacuum can be done by a rotation, at the cost of a sign in the half-integer case.

This argument by itself does not prove anything like the spin–statistics relation. To see why, consider a nonrelativistic spin-0 field described by a free Schrödinger equation. Such a field can be anticommuting or commuting. To see where it fails, consider that a nonrelativistic spin-0 field has no polarization, so that the product above is simply:

In the nonrelativistic theory, this product annihilates two particles at  and

and  , and has zero expectation value in any state. In order to have a nonzero matrix element, this operator product must be between states with two more particles on the right than on the left:

, and has zero expectation value in any state. In order to have a nonzero matrix element, this operator product must be between states with two more particles on the right than on the left:

Performing the rotation, all that we learn is that rotating the 2-particle state  gives the same sign as changing the operator order. This gives no additional information, so this argument does not prove anything.

gives the same sign as changing the operator order. This gives no additional information, so this argument does not prove anything.

Why the bogus argument fails

To prove spin–statistics theorem, it is necessary to use relativity, as is obvious from the consistency of the nonrelativistic spinless fermion, and the nonrelativistic spinning bosons. There are claims in the literature of proofs of spin–statistics theorem that do not require relativity,[7][8] but they are not proofs of a theorem, as the counterexamples show, rather they are arguments for why spin–statistics is "natural", while wrong-statistics is "unnatural". In relativity, the connection is required.

In relativity, there are no local fields that are pure creation operators or annihilation operators. Every local field both creates particles and annihilates the corresponding antiparticle. This means that in relativity, the product of the free real spin-0 field has a nonzero vacuum expectation value, because in addition to creating particles and annihilating particles, it also includes a part that creates and then annihilates a particle:

And now the heuristic argument can be used to see that  is equal to

is equal to  , which tells us that the fields cannot be anti-commuting.

, which tells us that the fields cannot be anti-commuting.

Proof

The essential ingredient in proving the spin/statistics relation is relativity, that the physical laws do not change under Lorentz transformations. The field operators transform under Lorentz transformations according to the spin of the particle that they create, by definition.

Additionally, the assumption (known as microcausality) that spacelike separated fields either commute or anticommute can be made only for relativistic theories with a time direction. Otherwise, the notion of being spacelike is meaningless. However, the proof involves looking at a Euclidean version of spacetime, in which the time direction is treated as a spatial one, as will be now explained.

Lorentz transformations include 3-dimensional rotations as well as boosts. A boost transfers to a frame of reference with a different velocity, and is mathematically like a rotation into time. By analytic continuation of the correlation functions of a quantum field theory, the time coordinate may become imaginary, and then boosts become rotations. The new "spacetime" has only spatial directions and is termed Euclidean.

A π rotation in the Euclidean xt plane can be used to rotate vacuum expectation values of the field product of the previous section. The time rotation turns the argument of the previous section into the spin–statistics theorem.

The proof requires the following assumptions:

- The theory has a Lorentz-invariant Lagrangian.

- The vacuum is Lorentz-invariant.

- The particle is a localized excitation. Microscopically, it is not attached to a string or domain wall.

- The particle is propagating, meaning that it has a finite, not infinite, mass.

- The particle is a real excitation, meaning that states containing this particle have a positive-definite norm.

These assumptions are for the most part necessary, as the following examples show:

- The spinless anticommuting field shows that spinless fermions are nonrelativistically consistent. Likewise, the theory of a spinor commuting field shows that spinning bosons are too.

- This assumption may be weakened.

- In 2+1 dimensions, sources for the Chern–Simons theory can have exotic spins, despite the fact that the three-dimensional rotation group has only integer and half-integer spin representations.

- An ultralocal field can have either statistics independently of its spin. This is related to Lorentz invariance, since an infinitely massive particle is always nonrelativistic, and the spin decouples from the dynamics. Although colored quarks are attached to a QCD string and have infinite mass, the spin-statistics relation for quarks can be proved in the short distance limit.

- Gauge ghosts are spinless fermions, but they include states of negative norm.

Assumptions 1 and 2 imply that the theory is described by a path integral, and assumption 3 implies that there is a local field which creates the particle.

The rotation plane includes time, and a rotation in a plane involving time in the Euclidean theory defines a CPT transformation in the Minkowski theory. If the theory is described by a path integral, a CPT transformation takes states to their conjugates, so that the correlation function

must be positive definite at x=0 by assumption 5, the particle states have positive norm. The assumption of finite mass implies that this correlation function is nonzero for x spacelike. Lorentz invariance now allows the fields to be rotated inside the correlation function in the manner of the argument of the previous section:

Where the sign depends on the spin, as before. The CPT invariance, or Euclidean rotational invariance, of the correlation function guarantees that this is equal to G(x). So

for integer spin fields and

for half-integer spin fields.

Since the operators are spacelike separated, a different order can only create states that differ by a phase. The argument fixes the phase to be −1 or 1 according to the spin. Since it is possible to rotate the space-like separated polarizations independently by local perturbations, the phase should not depend on the polarization in appropriately chosen field coordinates.

This argument is due to Julian Schwinger.[9]

Consequences

The spin-statistics theorem implies that half-integer spin particles are subject to the Pauli exclusion principle, while integer-spin particles are not. Only one fermion can occupy a given quantum state at any time, while the number of bosons that can occupy a quantum state is not restricted. The basic building blocks of matter such as protons, neutrons, and electrons are fermions. Particles such as the photon, which mediate forces between matter particles, are bosons.

There are a couple of interesting phenomena arising from the two types of statistics. The Bose–Einstein distribution which describes bosons leads to Bose–Einstein condensation. Below a certain temperature, most of the particles in a bosonic system will occupy the ground state (the state of lowest energy). Unusual properties such as superfluidity can result. The Fermi–Dirac distribution describing fermions also leads to interesting properties. Since only one fermion can occupy a given quantum state, the lowest single-particle energy level for spin-1/2 fermions contains at most two particles, with the spins of the particles oppositely aligned. Thus, even at absolute zero, the system still has a significant amount of energy. As a result, a fermionic system exerts an outward pressure. Even at non-zero temperatures, such a pressure can exist. This degeneracy pressure is responsible for keeping certain massive stars from collapsing due to gravity. See white dwarf, neutron star, and black hole.

Ghost fields do not obey the spin-statistics relation. See Klein transformation on how to patch up a loophole in the theorem.

Relation to representation theory of the Lorentz group

The Lorentz group has no non-trivial unitary representations of finite dimension. Thus it seems impossible to construct a Hilbert space in which all states have finite, non-zero spin and positive, Lorentz-invariant norm. This problem is overcome in different ways depending on particle spin-statistics.

For a state of integer spin the negative norm states (known as "unphysical polarization") are set to zero, which makes the use of gauge symmetry necessary.

For a state of half-integer spin the argument can be circumvented by having fermionic statistics.[10]

Literature

- Markus Fierz: Über die relativistische Theorie kräftefreier Teilchen mit beliebigem Spin. Helv. Phys. Acta 12, 3–17 (1939)

- Wolfgang Pauli: The connection between spin and statistics. Phys. Rev. 58, 716–722 (1940)

- Ray F. Streater and Arthur S. Wightman: PCT, Spin & Statistics, and All That. 5th edition: Princeton University Press, Princeton (2000)

- Ian Duck and Ennackel Chandy George Sudarshan: Pauli and the Spin-Statistics Theorem. World Scientific, Singapore (1997)

- Arthur S Wightman: Pauli and the Spin-Statistics Theorem (book review). Am. J. Phys. 67 (8), 742–746 (1999)

- Arthur Jabs: Connecting spin and statistics in quantum mechanics. http://arXiv.org/abs/0810.2399 (2014) (Found. Phys. 40, 776–792, 793–794 (2010))

Notes

- ↑ Dirac, Paul Adrien Maurice (1981-01-01). The Principles of Quantum Mechanics. Clarendon Press. p. 149. ISBN 9780198520115.

- ↑ Pauli, Wolfgang (1980-01-01). General principles of quantum mechanics. Springer-Verlag. ISBN 9783540098423.

- ↑ Markus Fierz (1939). "Über die relativistische Theorie kräftefreier Teilchen mit beliebigem Spin". Helvetica Physica Acta 12 (1): 3–37. doi:10.5169/seals-110930.

- ↑ Wolfgang Pauli (15 October 1940). "The Connection Between Spin and Statistics" (PDF). Physical Review 58 (8): 716–722. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.58.716.

- ↑ Richard Feynman (1961). Quantum Electrodynamics. Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-201-36075-2.

- ↑ Wolfgang Pauli (1950). "On the Connection Between Spin and Statistics". Progress of Theoretical Physics 5 (4): 526–543. doi:10.1143/ptp/5.4.526.

- ↑ Jabs, Arthur (5 April 2002). "Connecting Spin and Statistics in Quantum Mechanics". Foundations of Physics. Foundations of Physics 40 (7): 776–792. arXiv:0810.2399. Bibcode:2010FoPh...40..776J. doi:10.1007/s10701-009-9351-4. Retrieved May 29, 2011.

- ↑ Horowitz, Joshua (14 April 2009). "From Path Integrals to Fractional Quantum Statistics" (PDF).

- ↑ Julian Schwinger (June 15, 1951). "The Quantum Theory of Fields I". Physical Review 82 (6): 914–917. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.82.914.. The only difference between the argument in this paper and the argument presented here is that the operator "R" in Schwinger's paper is a pure time reversal, instead of a CPT operation, but this is the same for CP invariant free field theories which were all that Schwinger considered.

- ↑ Peskin, Michael E.; Schroeder, Daniel V. (1995). An Introduction to Quantum Field Theory. Addison-Wesley. ISBN 0-201-50397-2.

See also

References

- Paul O'Hara, Rotational Invariance and the Spin-Statistics Theorem, Foun. Phys. 33, 1349–1368(2003).

- Ian Duck and E. C. G. Sudarshan, Toward an understanding of the spin-statistics theorem, Am. J. Phys. 66 (4), 284–303 April 1998. Archived from the original on 2009-01-02.

External links

- A nice nearly-proof at John Baez's home page

- Animation of the Dirac belt trick with a double belt, showing that belts behave as spin 1/2 particles

- Animation of a Dirac belt trick variant showing that spin 1/2 particles are fermions