Spin–orbit interaction

In quantum physics, the spin–orbit interaction (also called spin–orbit effect or spin–orbit coupling) is an interaction of a particle's spin with its motion. The first and best known example of this is that spin–orbit interaction causes shifts in an electron's atomic energy levels due to electromagnetic interaction between the electron's spin and the magnetic field generated by the electron's orbit around the nucleus. This is detectable as a splitting of spectral lines. A similar effect, due to the relationship between angular momentum and the strong nuclear force, occurs for protons and neutrons moving inside the nucleus, leading to a shift in their energy levels in the nucleus shell model. In the field of spintronics, spin–orbit effects for electrons in semiconductors and other materials are explored for technological applications. The spin–orbit interaction is one cause of magnetocrystalline anisotropy.

Spin–orbit interaction in atomic energy levels

This section presents a relatively simple and quantitative description of the spin–orbit interaction for an electron bound to an atom, up to first order in perturbation theory, using some semiclassical electrodynamics and non-relativistic quantum mechanics. This gives results that agree reasonably well with observations. A more rigorous derivation of the same result would start with the Dirac equation, and achieving a more precise result would involve calculating small corrections from quantum electrodynamics.

Energy of a magnetic moment

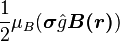

The energy of a magnetic moment in a magnetic field is given by:

where μ is the magnetic moment of the particle and B is the magnetic field it experiences.

Magnetic field

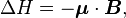

We shall deal with the magnetic field first. Although in the rest frame of the nucleus, there is no magnetic field acting on the electron, there is one in the rest frame of the electron. Ignoring for now that this frame is not inertial, in SI units we end up with the equation

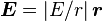

where v is the velocity of the electron and E the electric field it travels through. Now we know that E is radial so we can rewrite  .

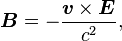

Also we know that the momentum of the electron

.

Also we know that the momentum of the electron  . Substituting this in and changing the order of the cross product gives:

. Substituting this in and changing the order of the cross product gives:

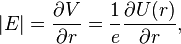

Next, we express the electric field as the gradient of the electric potential  . Here we make the central field approximation, that is, that the electrostatic potential is spherically symmetric, so is only a function of radius. This approximation is exact for hydrogen and hydrogen-like systems. Now we can say

. Here we make the central field approximation, that is, that the electrostatic potential is spherically symmetric, so is only a function of radius. This approximation is exact for hydrogen and hydrogen-like systems. Now we can say

where  is the potential energy of the electron in the central field, and e is the elementary charge. Now we remember from classical mechanics that the angular momentum of a particle

is the potential energy of the electron in the central field, and e is the elementary charge. Now we remember from classical mechanics that the angular momentum of a particle  . Putting it all together we get

. Putting it all together we get

It is important to note at this point that B is a positive number multiplied by L, meaning that the magnetic field is parallel to the orbital angular momentum of the particle, which is itself perpendicular to the particle's velocity.

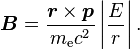

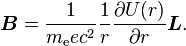

Magnetic moment of the electron

The magnetic moment of the electron is

where  is the spin angular momentum vector,

is the spin angular momentum vector,  is the Bohr magneton and

is the Bohr magneton and  is the electron spin g-factor. Here,

is the electron spin g-factor. Here,  is a negative constant multiplied by the spin, so the magnetic moment is antiparallel to the spin angular momentum.

is a negative constant multiplied by the spin, so the magnetic moment is antiparallel to the spin angular momentum.

The spin–orbit potential consists of two parts. The Larmor part is connected to the interaction of the magnetic moment of the electron with the magnetic field of the nucleus in the co-moving frame of the electron. The second contribution is related to Thomas precession.

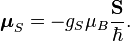

Larmor interaction energy

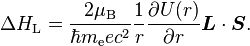

The Larmor interaction energy is

Substituting in this equation expressions for the magnetic moment and the magnetic field, one gets

Now, we have to take into account Thomas precession correction for the electron's curved trajectory.

Thomas interaction energy

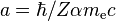

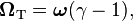

In 1926 Llewellyn Thomas relativistically recomputed the doublet separation in the fine structure of the atom.[1] Thomas precession rate,  , is related to the angular frequency of the orbital motion,

, is related to the angular frequency of the orbital motion,  , of a spinning particle as follows [2][3]

, of a spinning particle as follows [2][3]

where  is the Lorentz factor of the moving particle. The Hamiltonian producing the spin

precession

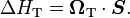

is the Lorentz factor of the moving particle. The Hamiltonian producing the spin

precession  is given by

is given by

To the first order in  , we obtain

, we obtain

Total interaction energy

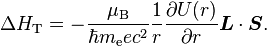

The total spin–orbit potential in an external electrostatic potential takes the form

The net effect of Thomas precession is the reduction of the Larmor interaction energy by factor 1/2 which came to be known as the Thomas half.

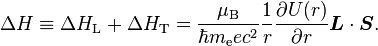

Evaluating the energy shift

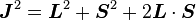

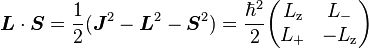

Thanks to all the above approximations, we can now evaluate the detailed energy shift in this model. In particular, we wish to find a basis that diagonalizes both H0 (the non-perturbed Hamiltonian) and ΔH. To find out what basis this is, we first define the total angular momentum operator

Taking the dot product of this with itself, we get

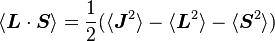

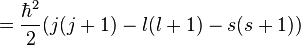

(since L and S commute), and therefore

It can be shown that the five operators H0, J2, L2, S2, and Jz all commute with each other and with ΔH. Therefore, the basis we were looking for is the simultaneous eigenbasis of these five operators (i.e., the basis where all five are diagonal). Elements of this basis have the five quantum numbers: n (the "principal quantum number") j (the "total angular momentum quantum number"), l (the "orbital angular momentum quantum number"), s (the "spin quantum number"), and jz (the "z-component of total angular momentum").

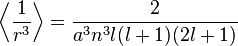

To evaluate the energies, we note that

for hydrogenic wavefunctions (here  is the Bohr radius divided by the nuclear charge Z); and

is the Bohr radius divided by the nuclear charge Z); and

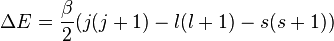

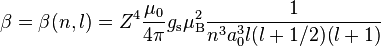

Final energy shift

We can now say

where

Spin–orbit interaction in solids

A crystalline solid (semiconductor, metal etc.) is characterized by its band structure. While on the overall scale (including the core levels) the spin–orbit interaction is still a small perturbation, it may play a relatively more important role if we zoom in to bands close to the Fermi level ( ). The atomic

). The atomic  interaction for example splits bands which would be otherwise degenerate and the particular form of this spin–orbit splitting (typically of the order of few to few hundred millielectronvolts) depends on the particular system. The bands of interest can be then described by various effective models, usually based on some perturbative approach. An example of how the atomic spin–orbit interaction influences the band structure of a crystal is explained in the article about Rashba interaction.

interaction for example splits bands which would be otherwise degenerate and the particular form of this spin–orbit splitting (typically of the order of few to few hundred millielectronvolts) depends on the particular system. The bands of interest can be then described by various effective models, usually based on some perturbative approach. An example of how the atomic spin–orbit interaction influences the band structure of a crystal is explained in the article about Rashba interaction.

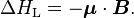

Examples of effective Hamiltonians

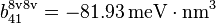

Hole bands of a bulk (3D) zinc-blende semiconductor will be split by  into heavy and light holes (which form a

into heavy and light holes (which form a  quadruplet in the

quadruplet in the  -point of the Brillouin zone) and a split-off band (

-point of the Brillouin zone) and a split-off band ( doublet). Including two conduction bands (

doublet). Including two conduction bands ( doublet in the

doublet in the  -point), the system is described by the effective eight-band model of Kohn and Luttinger. If only top of the valence band is of interest (for example when

-point), the system is described by the effective eight-band model of Kohn and Luttinger. If only top of the valence band is of interest (for example when  , Fermi level measured from the top of the valence band), the proper four-band effective model is

, Fermi level measured from the top of the valence band), the proper four-band effective model is

where  are the Luttinger parameters (analogous to the single effective mass of a one-band model of electrons) and

are the Luttinger parameters (analogous to the single effective mass of a one-band model of electrons) and  are angular momentum 3/2 matrices (

are angular momentum 3/2 matrices ( is the free electron mass). In combination with magnetization, this type of spin–orbit interaction will distort the electronic bands depending on the magnetization direction, thereby causing Magnetocrystalline anisotropy (a special type of Magnetic anisotropy).

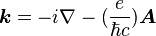

If the semiconductor moreover lacks the inversion symmetry, the hole bands will exhibit cubic Dresselhaus splitting. Within the four bands (light and heavy holes), the dominant term is

is the free electron mass). In combination with magnetization, this type of spin–orbit interaction will distort the electronic bands depending on the magnetization direction, thereby causing Magnetocrystalline anisotropy (a special type of Magnetic anisotropy).

If the semiconductor moreover lacks the inversion symmetry, the hole bands will exhibit cubic Dresselhaus splitting. Within the four bands (light and heavy holes), the dominant term is

where the material parameter  for GaAs (see pp. 72 in Winkler's book, according to more recent data the Dresselhaus constant in GaAs is 9 eVÅ3;[4] the total Hamiltonian will be

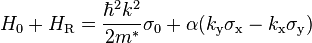

for GaAs (see pp. 72 in Winkler's book, according to more recent data the Dresselhaus constant in GaAs is 9 eVÅ3;[4] the total Hamiltonian will be  ). Two-dimensional electron gas in an asymmetric quantum well (or heterostructure) will feel the Rashba interaction. The appropriate two-band effective Hamiltonian is

). Two-dimensional electron gas in an asymmetric quantum well (or heterostructure) will feel the Rashba interaction. The appropriate two-band effective Hamiltonian is

where  is the 2 × 2 identity matrix,

is the 2 × 2 identity matrix,  the Pauli matrices and

the Pauli matrices and  the electron effective mass. The spin–orbit part of the Hamiltonian,

the electron effective mass. The spin–orbit part of the Hamiltonian,  is parametrized by

is parametrized by  , sometimes called the Rashba parameter (its definition somewhat varies), which is related to the structure asymmetry.

, sometimes called the Rashba parameter (its definition somewhat varies), which is related to the structure asymmetry.

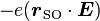

Above expressions for spin–orbit interaction couple spin matrices  and

and  to the quasi-momentum

to the quasi-momentum  , and to the vector potential

, and to the vector potential  of an AC electric field through the Peierls substitution

of an AC electric field through the Peierls substitution  . They are lower order terms of the Luttinger–Kohn

. They are lower order terms of the Luttinger–Kohn  expansion in powers of

expansion in powers of  . Next terms of this expansion also produce terms that couple spin operators of the electron coordinate

. Next terms of this expansion also produce terms that couple spin operators of the electron coordinate  . Indeed, a cross product

. Indeed, a cross product  is invariant with respect to time inversion. In cubic crystals, it has a symmetry of a vector and acquires a meaning of a spin–orbit contribution

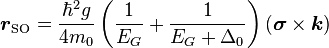

is invariant with respect to time inversion. In cubic crystals, it has a symmetry of a vector and acquires a meaning of a spin–orbit contribution  to the operator of coordinate. For electrons in semiconductors with a narrow gap

to the operator of coordinate. For electrons in semiconductors with a narrow gap  between the conduction and heavy hole bands, Yafet derived the equation[5][6]

between the conduction and heavy hole bands, Yafet derived the equation[5][6]

where  is a free electron mass, and

is a free electron mass, and  is a

is a  -factor properly renormalized for spin–orbit interaction. This operator couples electron spin

-factor properly renormalized for spin–orbit interaction. This operator couples electron spin  directly to the electric field

directly to the electric field  through the interaction energy

through the interaction energy  .

.

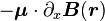

Electron spin in inhomogeneous magnetic field

Distinctive feature of spin-orbit interaction is presence in the Hamiltonian of a term that includes a product of orbital and spin operators. In atomic systems these are orbital and spin angular momenta  and

and  , respectively, and in solids the quasimomentum

, respectively, and in solids the quasimomentum  and Pauli matrices

and Pauli matrices  . This term couples orbital and spin dynamics. In particular, it allows manipulating electron spin by ac electric field through Electric Dipole Spin Resonance (EDSR).

. This term couples orbital and spin dynamics. In particular, it allows manipulating electron spin by ac electric field through Electric Dipole Spin Resonance (EDSR).

A similar effect can be achieved through the Larmor energy  if the magnetic field

if the magnetic field  is inhomogeneous. Then the derivatives such as

is inhomogeneous. Then the derivatives such as  play a role similar to spin-orbit coupling and allow electrical manipulation of electron spin.[7][8] In solids,

play a role similar to spin-orbit coupling and allow electrical manipulation of electron spin.[7][8] In solids,  should be changed to

should be changed to  , where

, where  is the Bohr magneton and

is the Bohr magneton and  is a

is a  -factor tensor;

-factor tensor;  can also be

can also be  -dependent.[9] In particular, this mechanism is currently used for EDSR in nanostructures.[10]

-dependent.[9] In particular, this mechanism is currently used for EDSR in nanostructures.[10]

See also

- Angular momentum diagrams (quantum mechanics)

- Angular momentum coupling

- Electric dipole spin resonance

- Kugel–Khomskii coupling

- Rashba effect

- Relativistic angular momentum

- Spherical basis

- Stark effect

- Zeeman effect

Textbooks

- E. U. Condon and G. H. Shortley (1935). The Theory of Atomic Spectra. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-09209-4.

- D. J. Griffiths (2004). Introduction to Quantum Mechanics (2nd edition). Prentice Hall.

- Landau, Lev; Lifshitz, Evgeny. "

72. Fine structure of atomic levels". Quantum Mechanics: Non-Relativistic Theory, Volume 3.

72. Fine structure of atomic levels". Quantum Mechanics: Non-Relativistic Theory, Volume 3.

- Yu, Peter Y.; Manuel Cardona. Fundamentals of Semiconductors.

- Winkler, Roland. Spin–Orbit Coupling Effects in Two-Dimensional Electron and Hole Systems.

Further reading

A. Manchon, H. C. Koo, J. Nitta, S. M. Frolov, and R. A. Duine, New perspectives for Rashba spin–orbit coupling, Nature Materials 14, 871-882 (2015), http://www.nature.com.ezp-prod1.hul.harvard.edu/nmat/journal/v14/n9/pdf/nmat4360.pdf

References

- ↑ L. H. Thomas, The motion of the spinning electron, Nature (London), 117, 514 (1926).

- ↑ L. Föppl and P. J. Daniell, Zur Kinematik des Born'schen starren Körpers, Nachrichten von der Königlichen Gesellschaft der Wissenschaften zu Göttingen, 519 (1913).

- ↑ C. Møller, The Theory of Relativity, (Oxford at the Claredon Press, London, 1952).

- ↑ J. J. Krich and B. I. Halperin, Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 226802 (2007)

- ↑ Y. Yafet,

factors and spin-lattice relaxation of conduction electrons, in: {\it Solid State Physics}, ed. by F. Seitz and D. Turnbull (Academic, NY), v. {\bf 14}, p. 98

factors and spin-lattice relaxation of conduction electrons, in: {\it Solid State Physics}, ed. by F. Seitz and D. Turnbull (Academic, NY), v. {\bf 14}, p. 98 - ↑ E. I. Rashba and V. I. Sheka, Electric-Dipole Spin-Resonances, in: Landau Level Spectroscopy, (North Holland, Amsterdam) 1991, p. 131

- ↑ E. I. Rashba, Spin Dynamics and Spin Transport,

Journal of Superconductivity: Incorporating Novel Magnetism,

, 137-144 (2005).

, 137-144 (2005).

- ↑ T. Tokura, W. G. van der Wiel, T. Obata and S. Tarucha, Coherent Single Electron Spin Control in a Slanting Zeeman Field, Phys. Rev. Lett.

, 047202 (2006)

, 047202 (2006) - ↑ Y. Kato, R. C. Myers, D.C. Driscoll, A.C. Gossard, J. Levy,

D.D. Awschalom, Science

, 1201 (2003)

, 1201 (2003) - ↑ M. Pioro-Ladriere , T. Obata, T. Tokura , Y.-S.Shin, T. Kubo, K. Yoshida, T. Taniyama, S. Tarucha, Nature Physics

, 776-779 (2008).

, 776-779 (2008).

![H_\text{KL}(k_\text{x},k_\text{y},k_\text{z})=-\frac{\hbar^2}{2m}\left[(\gamma_1+{\textstyle\frac52 \gamma_2}) k^2 -

2\gamma_2(J_\text{x}^2k_\text{x}^2+J_\text{y}^2k_\text{y}^2

+J_\text{z}^2k_\text{z}^2) -2\gamma_3 \sum_{m \ne n}J_mJ_nk_mk_n\right]](../I/m/484b803cf1dac03a282423844201af1f.png)

![H_{\text{D}3}=b_{41}^{8\text{v}8\text{v}}[(k_\text{x}k_\text{y}^2-k_\text{x}k_\text{z}^2)J_\text{x}+(k_\text{y}k_\text{z}^2-k_\text{y}k_\text{x}^2)J_\text{y}+(k_\text{z}k_\text{x}^2-k_\text{z}k_\text{y}^2)J_\text{z}]](../I/m/446e80d277bc3f4b856d6e7cbca05dc3.png)