United Airlines Flight 232

Photo of United Airlines Flight 232 from the NTSB report, with damage highlighted. | |

| Accident summary | |

|---|---|

| Date | July 19, 1989 |

| Summary | Uncontained engine failure due to faulty metallurgic forging of fan disk, loss of hydraulic systems and flight controls |

| Site |

Sioux Gateway Airport Sioux City, Iowa, United States |

| Passengers | 285[1] |

| Crew | 11[1] |

| Injuries (non-fatal) | 172[1] |

| Fatalities | 111[note 1][1] |

| Survivors | 185[1] |

| Aircraft type | McDonnell Douglas DC-10-10 |

| Operator | United Airlines |

| Registration | N1819U |

| Flight origin | Stapleton International Airport, Denver, Colorado |

| Stopover | O'Hare International Airport, Chicago, Illinois |

| Destination | Philadelphia International Airport, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania |

United Airlines Flight 232 was a DC-10 (registered N1819U) that on July 19, 1989 crash-landed in Sioux City, Iowa after suffering catastrophic failure of its tail-mounted engine, which led to the loss of all flight controls. The flight was en route from Stapleton International Airport in Denver, Colorado to O'Hare International Airport in Chicago. Of the 296 people on board, 111 died in the accident and 185 survived.[note 1] Despite the deaths, the accident is considered a prime example of successful crew resource management due to the large number of survivors and the manner in which the flight crew handled the emergency and landed the airplane without conventional control. The flight crew became well known as a result of their actions, in particular the captain, Alfred C. Haynes, and a DC-10 instructor on board who offered his assistance, Dennis E. Fitch.

General

The National Transportation Safety Board determined that the probable cause of this accident was the inadequate consideration given to human factors limitations in the inspection and quality control procedures used by United Airlines' engine overhaul facility. These resulted in the failure to detect a fatigue crack originating from a previously undetected metallurgical defect located in a critical area of the stage 1 fan disk that was manufactured by General Electric Aircraft Engines. The uncontained manner in which the engine failed resulted in high-speed metal fragments being hurled from the engine; these fragments penetrated the hydraulic lines of all three independent hydraulic systems on board the aircraft, which rapidly lost their hydraulic fluid. The subsequent catastrophic disintegration of the disk resulted in the liberation of debris in a pattern of distribution and with energy levels that exceeded the level of protection provided by design features of the hydraulic systems that operate the DC-10's flight controls; the flight crew lost their ability to operate nearly all of them. Despite these losses, the crew were able to attain and then maintain limited control by using the throttles to adjust thrust to the remaining wing-mounted engines. By using each engine independently, the crew made rough steering adjustments, and by using the engines together they were able to roughly adjust altitude. The crew guided the crippled jet to Sioux Gateway Airport and lined it up for landing on one of the runways. Without the use of flaps and slats, they were unable to slow down for landing, and were forced to attempt landing at a very high ground speed. The aircraft also landed at an extremely high rate of descent due to the inability to flare (reduce the rate of descent before touchdown by increasing pitch). As a result, upon touchdown the aircraft broke apart, rolled over and caught fire. The largest section came to rest in a cornfield next to the runway. Despite the ferocity of the accident, 185 (62.5%) passengers and crew survived owing to a variety of factors including the relatively controlled manner of the crash and the early notification of emergency services.[2]

Involved

Aircraft

The accident airplane, a McDonnell Douglas DC-10-10 (registration N1819U), was delivered in 1971 and had been owned by UAL since then. Before departure on the flight from Denver on July 19, 1989, the airplane had been operated for a total of 43,401 hours and 16,997 cycles. The airplane was powered by General Electric Aircraft Engines (GEAE) CF6-6D high bypass ratio turbofan engines.[2]

Flight crew

Captain Alfred C. Haynes, 57, was hired by United Airlines on February 23, 1956. He had 29,967 hours of total flight time with United Airlines, of which 7,190 was in the DC-10. He held Airline Transport Pilot Certificate, latest issue September 21, 1985, with type ratings in the DC-10 and B727. He was type rated in the DC-10 on May 11, 1983. On April 6, 1987, he was requalified as a DC-10 captain after having served as a B-727 captain since September 1985. His most recent proficiency check in the DC-10 was completed on April 26, 1989.

First Officer William R. Records, 48, was hired by National Airlines on August 25, 1969. He subsequently worked for Pan American World Airways. His first pilot activity at United Airlines was completion of the United Airlines indoctrination course (PAA Pilots to UAL) on December 26, 1985. He estimated that he had accumulated approximately 20,000 hours of total flight time. United's records indicate that he has accrued 665 hours of flight time as a DC-10 first officer. Records completed United's DC-10 transition course on August 8, 1988. This was also the date of his last proficiency check.

Second Officer Dudley J. Dvorak, 51, was hired by United Airlines on May 19, 1986. He estimated that he had approximately 15,000 hours of total flying time. United's records indicate that he had accumulated 1,903 hours as a second officer in the B-727 and 33 hours as a second officer in the DC-10. Dvorak completed DC-10 transition training on June 8, 1989. This was also the date of his last check ride.

Training Check Airman Captain Dennis E. Fitch, 46, was hired by United Airlines on January 2, 1968. He estimated that prior to his employment with United he had accrued between 1,400 and 1,500 hours of flight time with the Air National Guard. His total DC-10 time with United was 2,987 hours, of which 1,943 hours were accrued as a second officer, 965 hours as a first officer, and 79 hours as a captain. He was assigned as a DC-10 training check airman (TCA) at United's Training Center in Denver, Colorado.[2]

Events of crash

Take off, engine failure, hydraulic system unresponsive

Flight 232 took off at 14:09 (CDT) from Stapleton International Airport, Denver, Colorado, bound for O'Hare International Airport in Chicago with continuing service to Philadelphia International Airport.[2]

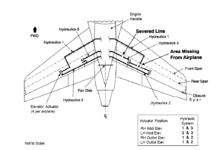

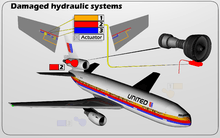

At 15:16, while the plane was in a shallow right turn at 37,000 feet, the fan disk of its tail-mounted General Electric CF6-6 engine failed and disintegrated. The debris from the failed disk was not contained by the engine's nacelle, a housing that protects the engine. Pieces of the disk penetrated the aircraft's tail section structure in numerous places, including the horizontal stabilizer. This fragmentation punctured the lines of all three hydraulic systems, allowing the fluid to rapidly drain away.[3]

The pilots felt a jolt go through the aircraft. Warning lights illuminated that indicated that the autopilot had disengaged and the tail-mounted number two engine was malfunctioning. Captain Haynes watched First Officer Records place his hands on the flight controls in response to the autopilot disconnecting and therefore focused his attention on the malfunctioning engine. Second Officer Dvorak obtained the engine failure checklist and read the first item: throttle power must be reduced to idle. Haynes was unable to move the throttle; the linkage had been jammed as a result of the engine failure.[3] The second item called for the fuel supply lever to be pulled to shutoff, but it would not move either. At this point, at Dvorak's suggestion, the firewall shutoff valve was actuated, and the fuel flow to the engine was shut off.[3] This part of the emergency took 14 seconds.[3]

Meanwhile, First Officer Records noticed that the airliner was off-course, and moved his control column to correct this, but the plane did not respond.[1] Records reported to Captain Haynes that he could not control the airplane. Haynes, having just shut off the fuel supply to the malfunctioning engine, looked at Records and was surprised by what he saw: Records had the control column turned all the way to the left, commanding maximum left aileron, and pulled all the way back, commanding maximum up elevator.[3] These inputs would never be utilized simultaneously in normal flight. What was more, despite these inputs, which command a roll to the left and the aircraft's nose to rise, the aircraft was instead banking to the right with the nose dropping.[3] Haynes took the flight controls and attempted to level the aircraft with his own control column.[3] When this was ineffective, both Haynes and Records utilized their control columns at the same time in an attempt to recover from the steepening bank. The aircraft still did not respond. Out of options, and in danger of the aircraft rolling into a completely inverted position (an unrecoverable situation which would result in a crash), the crew took the throttle for the left wing-mounted number 1 engine and reduced the power to idle, while also taking the throttle for the right wing-mounted number 3 engine and commanding maximum power. The resulting differential thrust (no power on the left side and maximum power on the right side) caused the airplane to slowly level out.[3]

With the imminent danger over, the crew began to diagnose the situation on the flight deck. Dvorak discovered that the pressure gauges and quantity gauges on his instrument panel for the three hydraulic systems were registering zero, and reported this to Haynes.[3] The three hydraulic systems were separate; a single event in one system would not disable the other systems, but lines for all three systems shared the same 10-inch-wide (250 mm) route through the tail where the engine debris had penetrated. There was no additional backup system. The flight crew quickly realized that the initial failure had left all hydraulic systems, and therefore all control surfaces, inoperative.[1] The crew called United Airlines' maintenance base using one of their radios, but as a total loss of hydraulics on the DC-10 was considered "virtually impossible", there were no procedures or guidelines for dealing with such an event.[1]

Help from Fitch, emergency landing and crash

Due to the damage in the tail, the plane had a continual tendency to turn right, and without flight controls it was difficult to maintain a stable course. The plane began to slowly oscillate vertically in a phugoid cycle, which is characteristic of planes in which control surface command is lost. With each iteration of the cycle the aircraft lost approximately 1,500 feet (460 m) of altitude. Dennis E. Fitch, an off-duty United Airlines DC-10 flight instructor, was seated in the first class section and, noticing the crew were having trouble controlling the airplane, offered his assistance to the flight attendants. Upon being informed that there was a DC-10 instructor on board, Haynes immediately invited him to the cockpit, hoping his instructional knowledge of the aircraft would help them regain control.[3]

When he entered the cockpit and looked at the hydraulic gauges, Fitch concluded that the situation was beyond anything he had ever faced.[3] The flight crew, while using the engines to control the airplane, were also still trying to fly the airplane using their control columns. Haynes asked Fitch to go into the passenger cabin and see if their control inputs were having any effect on the ailerons.[3] Fitch reported back that the ailerons were not moving at all. Despite this news, the crew would continue trying to fly the airplane with their control columns for the remainder of the flight, hopeful that it was at least having some effect. Fitch, his first task concluded, asked how he might be of further assistance. Haynes, still trying to fly the airplane with his control column while simultaneously working the throttles, asked Fitch to work the throttles instead. With one throttle in each hand, Fitch was able to mitigate the phugoid cycle and make rough steering adjustments.

Air traffic control (ATC) was contacted and an emergency landing at nearby Sioux Gateway Airport was organized. Haynes kept his sense of humor during the emergency, as recorded on the plane's cockpit voice recorder (CVR):

- Fitch: "I'll tell you what, we'll have a beer when this is all done."[4]

- Haynes: "Well I don't drink, but I'll sure as hell have one."[5][6]

and later:

- Sioux City Approach: "United Two Thirty-Two Heavy, the wind's currently three six zero at one one; three sixty at eleven. You're cleared to land on any runway."[4]

- Haynes: "[laughter] Roger. [laughter] You want to be particular and make it a runway, huh?"[4] (Haynes was alluding to the extreme difficulty in controlling the aircraft and their low chances of making it to a runway at all.)[7]

A more serious remark often quoted from Haynes was made when ATC asked the crew to make a left turn to keep them clear of the city:

- Haynes: "Whatever you do, keep us away from the city."[8]

Haynes later noted that "We were too busy [to be scared]. You must maintain your composure in the airplane or you will die. You learn that from your first day flying."[9]

As the crew began to prepare for arrival at Sioux City, they questioned whether they should deploy the landing gear or belly-land the aircraft with the gear retracted. They decided that having the landing gear down would provide some shock absorption on impact.[10] The complete hydraulic failure left the landing gear lowering mechanism inoperative. Two options were available to the flight crew. The DC-10 is designed such that if hydraulic pressure to the landing gear is lost, the gear will fall down slightly and rest on the landing gear doors. Placing the regular landing gear handle in the down position will unlock the doors mechanically, and the doors and landing gear will then fall down into place and lock due to gravity.[10] An alternative system is also available using a lever in the cockpit floor to cause the landing gear to fall into position.[11] This lever has the added benefit of unlocking the outboard ailerons, which are not used in high-speed flight and are locked in a neutral position.[10] The crew hoped that there might be some trapped hydraulic fluid in the outboard ailerons and that they might regain some use of flight controls by unlocking them. They elected to extend the gear with the alternative system.[10] Although the gear deployed successfully, there was no change in the controllability of the aircraft.[1]

Landing was originally planned on the 9,000-foot (2,700 m) Runway 31. Difficulties in controlling the aircraft made lining up almost impossible. While dumping some of the excess fuel, the plane executed a series of mostly right-hand turns (it was easier to turn the plane in this direction) with the intention of lining up with Runway 31. When they came out they were instead lined up with the shorter (6,888 ft) and closed Runway 22, and had little capacity to maneuver.[1] Fire trucks had been placed on Runway 22,[3] anticipating a landing on nearby Runway 31, so all the vehicles were quickly moved out of the way before the plane touched down. Runway 22 had been permanently closed a year earlier in 1988.[1]

Fitch continued to control the aircraft's descent by adjusting engine thrust. With the loss of all hydraulics, the crew were unable to control airspeed independent from sink rate. On final descent, the aircraft was going 240 knots and sinking at 1,850 feet per minute (approximately 440 km/h forward and 34 km/h downward speed), while a safe landing would require 140 knots and 300 feet per minute (approximately 260 and 5 km/h respectively). Fitch needed a seat for landing; Dvorak offered up his own, as it could be moved to a position behind the throttles.[1] Dvorak sat in the cockpit's jump seat for landing. Right before touchdown, the aircraft began a downward phugoid and veered right. The flight crew had no time to react. The tip of the right wing hit the runway first, spilling fuel, which ignited immediately. The tail section broke off from the force of the impact, and the rest of the aircraft bounced several times, shedding the landing gear and engine nacelles and breaking the fuselage into several main pieces. On the final impact, the right wing was shorn off and the main part of the aircraft skidded sideways, rolled over onto its back, and slid to a stop upside-down in a corn field to the right of Runway 22. Witnesses reported that the aircraft "cartwheeled" end-over-end, but the investigation did not confirm this.[1] The reports were due to misinterpretation of the video of the crash that showed the flaming right wing tumbling end-over-end and the intact left wing, still attached to the fuselage, rolling up and over as the fuselage flipped over.

Post-crash response

Injuries to persons

Of the 296 people on board, 111 died in the crash. Most were killed by injuries sustained in the multiple impacts, but 35 people in the middle fuselage section directly above the fuel tanks died from smoke inhalation in the post-crash fire. Of those, 24 had no traumatic blunt-force injuries. The majority of the 185 survivors were seated behind first class and ahead of the wings.[8] Many passengers were able to walk out through the ruptures to the structure, and in many cases got lost in the high field of corn adjacent to the runway until rescue workers arrived on the scene and escorted them to safety.

Of all of the passengers:[1]

- 35 died due to smoke inhalation (none were in first class)

- 76 died for reasons other than smoke inhalation (17 in first class)

- 47 were seriously injured (eight in first class)

- 125 had minor injuries (one in first class)

- 13 had no injuries (none in first class)

The passengers who died for reasons other than smoke inhalation were seated in rows 1–4, 24–25 and 28–38. Passengers who died due to smoke inhalation were seated in rows 14, 16 and 22–30. The person assigned to 20H moved to an unknown seat and died of smoke inhalation.

One crash survivor died 31 days after the accident; he was classified according to NTSB regulations as a survivor with serious injuries.[1]

Fifty-two children, including four "lap children" without their own seats, were on board the flight due to the United Airlines "Children's Day" promotion. Eleven children, including one lap child, died.[12] Many of the children had traveled alone.[13]

Rescuers initially ignored the cockpit, as it had been compressed in the crash to approximately waist high and was completely unrecognizable. It was not until 35 minutes after the crash that rescuers discovered that the debris was the cockpit and that the four pilots were still alive inside. All four recovered from their injuries and returned to work: Haynes, Records and Dvorak returned in three months, while Fitch, more seriously injured than the others, returned in 11 months.[3]

Investigation

National Transportation Safety Board officials were on scene within hours of the accident. N1819U had been in service since 1972 and was 17 years old, about mid-life for a DC-10, when the accident occurred. The rear section of the aircraft containing the number two engine was intact. Because of this, investigators were easily able to see inside engine number 2. As the investigation unfolded, it became apparent that the entire fan disk and blade assembly from engine number 2, a component approximately 8 feet (2.4 m) in diameter and made of titanium alloy, was missing from the accident scene.[1] Despite an extensive search in the weeks following the crash, the missing disk and blade assembly could not be located. Realizing that that disk potentially held the key to understanding the reasons for the engine failure, the engine's manufacturer, General Electric, offered a $50,000 reward to whoever located the disk, and $1,000 for each fan blade.[14] On October 10, 1989, three months after the crash, Janice Sorenson, a farmer harvesting corn near Alta, Iowa, felt resistance on her combine, and after getting out to investigate, discovered most of the fan disk with a number of blades still attached partially buried in her cornfield.[14] The rest of the fan disk and most of the additional blades were located later in the harvest.

Investigators discovered an impurity and fatigue crack in the disk. Titanium reacts with air when melted, which creates impurities which can initiate fatigue cracks like that found in the crash disk. To prevent this, the ingot that would become the fan disk was formed using a "double vacuum" process: the raw materials were melted together in a vacuum, allowed to cool and solidify, then melted in a vacuum once more. After the double vacuum process, the ingot was shaped into a billet, a sausage-like form about 16 inches in diameter, and tested using ultrasound to look for defects. Defects were located and the ingot was further processed to remove them, but some contamination remained. (GE later changed to an improved triple-vacuum process because of their investigation into failing rotating titanium engine parts.)[1]

The contamination caused what is known as a hard alpha inclusion, a brittle part of the metal, which cracked during forging and then fell out during final machining. This formed a cavity with microscopic cracks at the edges. For the next 18 years, the crack grew slightly each time the engine was powered up and brought to operating temperature. Eventually the crack grew large enough to cause structural failure of the disk.[1]

Significant irregularities and gaps in GE Aircraft engines’ and its suppliers’ manufacturing records of the crash disk noted in the NTSB report[1] leave doubts about the origins of the crash disk. Records found after the accident indicated that two rough-machined forgings having the serial number of the crash disk had been routed through GEAE manufacturing. Records indicated that Alcoa supplied GE with TIMET titanium forgings for one disk with the serial number of the crash disk. Some records show that this disk “was rejected for an unsatisfactory ultrasonic indication”, that an outside lab performed an ultrasound inspection of this disk, that this disk was subsequently returned to GE, and that this disk should have been scrapped. The FAA report stated “There is no record of warranty claim by GEAE for defective material and no record of any credit for GEAE processed by Alcoa or TIMET”.[1]

GE records of the second disk having the serial number of the crash disk indicate that it was made with an RMI titanium billet supplied by Alcoa. Research of GE records showed no other titanium parts were manufactured at GE from this RMI titanium billet during the period of 1969 to 1990. GE records indicate that final finishing and inspection of the crash disk were completed on December 11, 1971. Alcoa records indicate that this RMI titanium billet was first cut in 1972 and that all forgings made from this material were for airframe parts.[1] If the Alcoa records were accurate, the RMI titanium could not have been used to manufacture the crash disk, indicating that the initially rejected TIMET disk with “an unsatisfactory ultrasonic indication” was the crash disk.

CF6 engines like that containing the crash disk were used to power many civilian and military aircraft at the time of the crash. Due to concerns that the accident could recur, a large number of disks that were in service were examined by ultrasound for indications of defects. At least two “sister disks” were found to have defects like that of the crash disk. Prioritization and efficiency of inspections of the many engines under suspicion would have been aided by determination of the titanium source of the crash disk. Chemical analyses of the crash disk intended to determine its source were inconclusive. The NTSB report stated that if examined disks were not from the same source, “the records on a large number of GEAE disks are suspect. It also means that any AD action that is based on the serial number of a disk could fail to have its intended effect because suspect disks could remain in service.” [1] The FAA report did not explicitly address the impact of these uncertainties on operations of military aircraft that might have contained a suspect disk.

Cause

The investigation, while praising the actions of the flight crew for saving lives, would later identify the cause of the accident as a failure by United Airlines maintenance processes and personnel to detect an existing fatigue crack.[1] The Probable Cause in the report by the NTSB read as follows:

The National Transportation Safety Board determines that the probable cause of this accident was the inadequate consideration given to human factors limitations in the inspection and quality control procedures used by United Airlines' engine overhaul facility which resulted in the failure to detect a fatigue crack originating from a previously undetected metallurgical defect located in a critical area of the stage 1 fan disk that was manufactured by General Electric Aircraft Engines. The subsequent catastrophic disintegration of the disk resulted in the liberation of debris in a pattern of distribution and with energy levels that exceeded the level of protection provided by design features of the hydraulic systems that operate the DC-10's flight controls.[1]

Post-crash analysis of the crack surfaces showed the presence of a penetrating fluorescent dye used to detect cracks during maintenance. The presence of the dye indicated that the crack was present and should have been detected at a prior inspection. The detection failure arose from poor attention to human factors in United Airlines' specification of maintenance processes.[1]

Influence on the industry

The National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) investigation, after subsequent reconstructions of the accident in flight simulators, deemed that training for such an event involved too many factors to be practical. While some level of control was possible, no precision could be achieved, and a landing under these conditions was stated to be "a highly random event".[1] The NTSB further noted that "under the circumstances the UAL[note 2] flight crew performance was highly commendable and greatly exceeded reasonable expectations."[1]

The manufacturing process for titanium was changed in order to eliminate the type of gaseous anomaly that served as the starting point for the crack. Newer batches of titanium use much higher melting temperatures and a "triple vacuum" process in an attempt to eliminate such impurities.[15]

Because this type of aircraft control (with loss of control surfaces) is difficult for humans to achieve, some researchers have attempted to integrate this control ability into the computers of fly-by-wire aircraft. Early attempts to add the ability to real airplanes were not very successful; the software was based on experiments conducted in flight simulators where jet engines are usually modeled as "perfect" devices with exactly the same thrust on each engine, a linear relationship between throttle setting and thrust, and instantaneous response to input. Later, computer models were updated to account for these factors, and planes have been successfully flown with this software installed.[16]

Newer aircraft designs such as the McDonnell Douglas MD-11 have incorporated hydraulic fuses to isolate a punctured section and prevent a total loss of hydraulic fluid. Following the UAL 232 accident, such fuses were installed in the number 3 hydraulic system in the area below the number 2 engine on all DC-10 aircraft to ensure sufficient control capability remained if all three hydraulic system lines should be damaged in the tail area.[8] Although elevator and rudder control would be lost, the aircrew would still be able to control the aircraft's pitch (up and down) with stabilizer trim, and would be able to control roll (left and right) with some of the aircraft's ailerons and spoilers. Although not an ideal situation, the system provides a greater measure of control than was available to the crew of United 232.

It is still possible to lose all three hydraulic systems if serious damage occurs elsewhere, as nearly happened to a cargo airliner in 2002 during takeoff when a main gear tire exploded in the wheel well area. The damage in the left wing area caused total fluid loss from the number 1 and the number 2 hydraulic systems. The number 3 system was dented but not penetrated. DC-10s still have no fuse protection for any of the three hydraulic systems in the event of an exploding main gear tire.[17]

Of the four children deemed too young to require seats of their own ("lap children"), one died from smoke inhalation.[1] The NTSB added a safety recommendation to the FAA on its "List of Most Wanted Safety Improvements" in May 1999 suggesting a requirement for children under 2 to be safely restrained, which was removed in November 2006.[18][19] The accident sparked a campaign led by United Flight 232's senior flight attendant, Jan Brown Lohr, for all children to have seats on aircraft.[20]

The accident has since become a prime example of successful Crew Resource Management.[21] For much of aviation's history, the captain was considered the final authority, and crews were to respect the captain's expertise and not question him. This began to change in the 1970s, especially after the Tenerife airport disaster. Crew Resource Management, while still considering the captain the final authority, instructs crewmembers to speak up when they detect a problem, and instructs captains to listen to their concerns. United Airlines instituted a Crew Resource Management class in the early 1980s. The NTSB would later credit this training as valuable toward the success of United 232's crew in handling their emergency.[1] The FAA made Crew Resource Training mandatory in the aftermath of the accident.

Factors contributing to survival rate

Of the 296 people aboard, 111 were killed in the crash, while 185 survived.[note 1] Captain Haynes later told of three contributing factors regarding the time of day that allowed for a greater number of passengers surviving:

- The accident occurred during daylight hours in good weather;

- The accident occurred as a shift change was occurring at both a regional trauma center and a regional burn center in Sioux City, allowing for more medical personnel to treat the injured;

- The accident occurred when the Iowa Air National Guard was on duty at Sioux Gateway Airport, allowing for 285 trained personnel to assist with triage and evacuation of the injured.

"Had any of those things not been there," Haynes said, "I'm sure the fatality rate would have been a lot higher."[22]

Captain Haynes also credited Crew Resource Management as being one of the factors that saved his own life, and many others.

…the preparation that paid off for the crew was something … called Cockpit Resource Management… Up until 1980, we kind of worked on the concept that the captain was THE authority on the aircraft. What he said, goes. And we lost a few airplanes because of that. Sometimes the captain isn't as smart as we thought he was. And we would listen to him, and do what he said, and we wouldn't know what he's talking about. And we had 103 years of flying experience there in the cockpit, trying to get that airplane on the ground, not one minute of which we had actually practised, any one of us. So why would I know more about getting that airplane on the ground under those conditions than the other three. So if I hadn't used CRM, if we had not let everybody put their input in, it's a cinch we wouldn't have made it.[23]

As with the Eastern Air Lines Flight 401 crash of a similarly-sized Lockheed L-1011 in 1972, the relatively shallow angle[note 3] of descent likely played a large part in the relatively high survival rate. The National Transportation Safety Board concluded that under the circumstances, "a safe landing was virtually impossible."[1]

Notable survivors

- Spencer Bailey – subject of a famous photograph showing Lt. Colonel Dennis Nielsen carrying the three-year-old survivor to safety.[24] His brother Brandon also survived the crash, but their mother, Francie, did not.[24] A statue in part of Sioux City's riverfront development is based on the picture.[25] The 1994 memorial commemorates the rescue efforts by the Sioux City community following the crash, and features contemplative areas and a tree-lined approach with plaques describing the accident.[24] Bailey is now the executive editor of Surface and is a contributor to The New York Times Magazine. He now lives in New York City.[26]

- Jerry Schemmel – radio announcer for the Colorado Rockies, Denver's Major League Baseball team, and a former radio announcer for the Denver Nuggets, Denver's National Basketball Association basketball team. He wrote a book about United Airlines Flight 232 titled Chosen to Live, and was credited with saving the life of a child in the crash.[27]

- Michael R. Matz – trainer of the 2006 Kentucky Derby favorite and winner Barbaro and the 2012 Belmont Stakes winner Union Rags. He was credited with saving the lives of four children in the crash, three from the same family. Matz competed for the US in equestrian show jumping in several Summer Olympics, winning silver in the team show jumping event at the 1996 games.[28]

- Alfred C. Haynes – the captain of United Airlines flight 232. His actions, along with the actions of the flight crew, are credited for saving the lives of the survivors.[1] He returned to flying after recovering from his injuries and would continue to fly DC-10s as captain until reaching mandatory retirement age in 1991. Several rescuers, crew members and passengers from flight 232 flew with Haynes on his final flight.[29] Haynes became a public speaker soon after the accident, giving speeches about what happened aboard flight 232. He continued these after retirement, and credits this work with helping his own healing process.[30]

- Dennis E. Fitch – a DC-10 pilot and instructor, he helped Captain Haynes fly United Airlines Flight 232. "For the 30 minutes I was up there," Fitch said, "I was the most alive I've ever been. That is the only way I can describe it to you."[22] Fitch died at the age of 69 on May 7, 2012, after a battle with brain cancer.

- Pete Wernick – banjo player with the Hot Rize bluegrass band and instructor, he was on his way to a festival in the Albany, New York, area. Wernick walked away from the crash with his young son, and along with his wife, they took a later flight to go to the festival. He gave his personal account of the day's events in the song "A Day in '89 (You Never Know)". Wernick has yet to release a recording of the song, but has published the lyrics on his website.[31]

- Jan Brown Lohr – United 232's Senior Flight Attendant. She was forced by regulation to ask parents with "lap children" aboard flight 232 to place their children on the cabin floor during the flight's final moments before impact. One of four children died from smoke inhalation. The dead child's mother confronted Lohr at the crash scene. Since then, Lohr has lobbied in Washington D.C. for new federal regulations requiring all children to have a seat belt on every flight.[20]

Depictions

- The accident was the subject of the 1992 television movie A Thousand Heroes, also known as Crash Landing: The Rescue of Flight 232.[32]

- It was featured in an episode of Seconds From Disaster on the National Geographic Channel and MSNBC Investigates on the MSNBC news channel.

- The History Channel distributed a documentary named Shockwave; a portion of Episode 7 (originally aired January 25, 2008) detailed the events of the crash.

- The episode "A Wing and a Prayer" of Survival in the Sky (UK title: Black Box) featured the accident.

- The Biography Channel series I Survived... explained in detail the events of the crash through passenger Jerry, flight attendant Jan Brown Lohr, and pilot Alfred Haynes.

- Mayday (also known as Air Crash Investigation in the UK, Australia and Asia and Air Emergency or Air Disasters in the United States) produced a one-hour docudrama about the crash entitled "Impossible Landing".

- The episode "Crisis in the Cockpit" (Season 2, Episode 1) of "Why Planes Crash" on The Weather Channel featured the accident.

- The 1999 play Charlie Victor Romeo (made into a film in 2013) dramatically reenacted the incident using transcripts from the flight deck voice recorder.

- The 1991 novel Cold Fire, by Dean Koontz, includes a fictional crash based on Flight 232.

- The 1993 film Fearless portrayed a fictional air crash based in part on the crash of Flight 232.

Survivor accounts

- Dennis Fitch described his experiences in Errol Morris's television show First Person.[33]

- Martha Conant told her story of survival to her daughter-in-law, Brittany Conant, on "Storycorps" during NPR's Morning Edition of January 11, 2008.[34]

- Flight 232: A Story of Disaster and Survival by Laurence Gonzales (2014, W. W. Norton & Company; ISBN 978-0-393-24002-3).

- Miracle in the Cornfield – an inside survivor narrative by Joseph Trombello (1999, PrintSource Plus, Appleton, WI; ISBN 0966981502).

Similar accidents

The odds against all three hydraulic systems failing simultaneously had previously been calculated as high as a billion to one.[35] Yet such calculations assume that multiple failures must have independent causes, an unrealistic assumption, and similar flight control failures have indeed occurred:

- In 1971 a Pan American 747 struck approach light structures for the reciprocal runway as it lifted off the runway at San Francisco Airport. Major damage to the belly and landing gear resulted, which caused the loss of hydraulic fluid from three of its four flight control systems. The fluid which remained in the fourth system gave the captain very limited control of some of the spoilers, ailerons, and one inboard elevator. That was sufficient to circle the plane while fuel was dumped and then to make a hard landing. There were no fatalities, but there were some injuries.[36]

- In 1981, a Lockheed L-1011, operating as Eastern Airlines Flight 935, suffered a similar failure of its tail-mounted number two engine. The shrapnel from that engine inflicted damage on all four of its hydraulic systems, which were also close together in the tail structure. Fluid was lost in three of the four systems. The fourth hydraulic system was impacted with shrapnel, but not punctured. The hydraulic pressure remaining in that fourth system enabled the captain to land the plane safely with some limited use of the outboard spoilers, the inboard ailerons, and the horizontal stabilizer, plus differential engine power of the remaining two engines. There were no injuries.[37]

- On August 12, 1985, Japan Airlines Flight 123, a Boeing 747-146SR, suffered a rupture of the pressure bulkhead in its tail section, caused by undetected damage during a faulty repair to the rear bulkhead after a tailstrike seven years earlier. Pressurized air subsequently rushed out of the bulkhead and blew off the plane's vertical stabilizer, also severing all four of its hydraulic control systems. The pilots were able to keep the plane airborne for almost 30 minutes using differential engine power, but without any hydraulics or the stabilizing force of the vertical stabilizer, the plane eventually crashed in mountainous terrain. There were only 4 survivors among the 524 on board. This accident is the deadliest single-aircraft accident in history.[38]

- In 1994, RA85656, a Tupolev Tu-154 operating as Baikal Airlines Flight 130, crashed near Irkutsk shortly after departing from Irkutsk Airport, Russia. Damage to the starter caused a fire in engine number two (located in the rear fuselage). High temperatures during the fire destroyed the tanks and pipes of all three hydraulic systems. The crew lost control of the aircraft. The unmanageable plane, at a speed of 275 knots, hit the ground at a dairy farm and burned. All passengers and crew, as well as a dairyman on the ground, died.[39]

- In 2003, OO-DLL, a DHL Airbus A300, was struck by a surface-to-air missile shortly after departing from Baghdad International Airport, Iraq. The missile struck the port-side wing, rupturing a fuel tank and causing the loss of all three hydraulic systems. With the flight controls disabled, the crew used differential thrust to execute a safe landing at Baghdad.[40]

The disintegration of a turbine disc, leading to loss of control, was a direct cause of two major aircraft disasters in Poland:

- On March 14, 1980, LOT Polish Airlines Flight 007, an Ilyushin Il-62, attempted a go-around when the crew experienced troubles with a gear indicator. When thrust was applied, the low pressure turbine disc in engine number 2 disintegrated because of material fatigue; parts of the disc damaged engines number 1 and 3 and severed control pushers for both horizontal and vertical stabilizers. After 26 seconds of uncontrolled descent, the aircraft crashed, killing all 87 people on board.[41]

- On May 9, 1987, improperly assembled bearings in Il-62M engine number 2 on LOT Polish Airlines Flight 5055 overheated and exploded during cruise over the village of Lipinki, causing the shaft to break in two; this caused the low-pressure turbine disc to spin to enormous speeds and disintegrate, damaging engine number 1 and cutting the control pushers. The crew managed to return to Warsaw, using nothing but trim tabs to control the crippled aircraft, but on the final approach, the trim controlling links burned and the crew completely lost control over the aircraft. Soon after, it crashed on the outskirts of Warsaw; all 183 on board perished. Had the plane stayed airborne for 40 seconds more, it would have been able to reach the runway.[42]

See also

- Flight with disabled controls

- American Airlines Flight 96

- American Airlines Flight 191

- Japan Airlines Flight 123

- Qantas Flight 32

- Tan Son Nhut C-5 accident

- Turkish Airlines Flight 981

- US Airways Flight 1549

- John Kenneth Stille - Organic chemist who was killed in the crash.

Notes

- 1 2 3 One passenger died 31 days after the accident; in accordance with NTSB regulations, he is classified as a survivor with "serious" injuries.

- ↑ UAL is the three-letter designator code for United Airlines.

- ↑ Angle of descent and Rate of descent are two different things. The aircraft approached at a high rate of descent but a shallow angle.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 "NTSB/AAR-90/06" (PDF). NTSB. Retrieved 2011-03-15.

- 1 2 3 4 http://www.airdisaster.com/reports/ntsb/AAR90-06.pdf

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Haynes, Al. "Special report". Airdisaster.com. Retrieved 2006-09-15.

- 1 2 3 "Aviation Safety Network CVR/FDR: United Airlines DC-10-10 – 19 JUL 1989" (PDF). Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved 25 March 2011.

- ↑ Playback of original CVR recording on “A Wing and a Prayer” episode of TV series Black Box, 1996.

- ↑ last cockpit voice recording of United Flight 232 at 0:18 Retrieved January 10, 2013.

- ↑ "30 minutes that changed everything". CBS News. 1998-08-20. Retrieved 2006-12-05.

- 1 2 3 Macarthur Job (1996). Air Disaster Volume 2, Aerospace Publications, ISBN 1-875671-19-6: pp.186–202

- ↑ Gates, Dominic (2009-07-19). "20 years ago, pilot's heroic efforts saved 185 people as plane crashed". Seattle Times. Retrieved 2009-07-19.

- 1 2 3 4 Haynes, Al. "The Crash of United Flight 232". Retrieved 16 March 2011.

- ↑ "DC-10 Flight Crew Operating Manual". Retrieved 16 March 2011.

- ↑ United Airlines Flight 232 episode, Seconds From Disaster

- ↑ "The Crash of United Flight 232 by Capt. Al Haynes". Clear-prop.org. Retrieved 2011-03-15.

- 1 2 "Key Piece of Doomed DC-10 Found in Field". Los Angeles Times. 1989-10-12. Retrieved 2011-03-15.

- ↑ Thomas, Malcolm. "Titanium in Aero Engines, Trends & Developments" (PDF). Rolls Royce. Retrieved April 10, 2011.

- ↑ "Active Home Page". Past Research Projects. NASA. Retrieved 2006-06-01.

- ↑ "NTSB/Safety Recommendation to FAA". NTSB, August 21, 2003.

- ↑ "Aviation Issues". 2006-08-13. Archived from the original on August 13, 2006. Retrieved 2011-03-15.

- ↑ "Modifications to NTSB Most Wanted List: List of Transportation Safety Improvements after September 1990" (PDF). NTSB.

- 1 2 "The power of stories over statistics". British Medical Journal. Retrieved 2006-09-15.

- ↑ How Swift Starting Action Teams Get off the Ground: What United Flight 232 and Airline Flight Crews Can Tell Us About Team Communication Management Communication Quarterly, Vol. 19, No. 2, November 2005

- 1 2 Nicholas Faith (1996, 1998). Black Box, Boxtree, ISBN 0-7522-2118-3: pp.158–165

- ↑ Capt. Al Haynes (May 24, 1991). "The Crash of United Flight 232". Retrieved 2013-06-04. Presentation to NASA Dryden Flight Research Facility staff.

- 1 2 3 "Flight 232: Snapshots of tragedy and triumph". Retrieved 30 March 2011.

- ↑ Flight 232 Memorial and Statue – Sioux City, IA

- ↑ http://www.linkedin.com/in/spencercbailey?_mSplash=1

- ↑ Schemmel, Jerry; Simpson, Kevin (1996). Chosen to Live: The Inspiring Story of a Flight 232 Survivor. Victory Publishing. ISBN 0-9652086-5-6.

- ↑ Wallechinsky, David and Loucky, Jaime (2008). "Equestrian: Jumping (Prix des Nations), Team". In The Complete Book of the Olympics: 2008 Edition. London: Aurum Pres Limited. pp. 582, 584–5.

- ↑ Anima, Tina (27 August 1991). "Hero's Last Flight: Pilot Al Haynes Retires". Seattle Times. Retrieved 19 March 2011.

- ↑ Zerschling, Lynn (1 February 2010). "Eight Questions with retired Capt. Al Haynes". Sioux City Journal. Retrieved 19 March 2011.

- ↑ Lyrics to Pete Wernick's "A Day in '89 (You Never Know)" from drbanjo.com (Wernick's official site).

- ↑ "Crash Landing: The Rescue of Flight 232". IMDB. Retrieved 2006-09-15.

- ↑ "Errol Morris’ First Person Episode 10". Retrieved 2011-03-15.

- ↑ Morning Edition (2008-01-11). "After Disaster, a Survivor Sheds Her Regrets". NPR. Retrieved 2011-03-15.

- ↑ "Eyewitness Report:United 232". AirDisaster.Com. Retrieved 2008-06-04.

- ↑ "Aircraft Accident Report Pan American World Airways Inc Boeing 747, N747PA Flight 845" (PDF). NTSB. Retrieved 11 April 2011.

- ↑ "Aircraft Accident Report Eastern Airlines Flight 935" (PDF). NTSB. Retrieved 11 April 2011.

- ↑ "Japan Airlines Flight 123, Boeing 747-SR100, JA8119". FAA. Retrieved 11 April 2011.

- ↑ "Aviation Safety Network Accident Description". Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved 11 April 2011.

- ↑ "Aviation Safety Network Criminal Occurrence Description". Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved 11 April 2011.

- ↑ "Aviation Safety Network Accident Description". Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved 11 April 2011.

- ↑ "Aviation Safety Network Accident Description". Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved 11 April 2011.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to United Airlines Flight 232. |

| Wikinews has related news: 20 years on: Sioux City, Iowa remembers crash landing that killed 111 |

- Accident description at the Aviation Safety Network

- NTSB Accident report of United Airlines Flight 232

- Cockpit voice-recorder transcript (pdf) (NB contains error)

- A talk given by the pilot describing the crash at NASA Dryden in 1991

- Siouxland Chamber Of Commerce: Remembering Flight 232 (Picture of memorial depicting Lt. Colonel Dennis Nielsen carrying Spencer Bailey)

- "17th Anniversary Tribute of Flight 232"

- News report with video of crash landing of Flight 232, ABC News, July 19, 1989

- Pre-crash landing photos from Airliners.net

- Martha Conant tells her story of surviving the crash.

- Crash Landing: The Rescue of Flight 232 at the Internet Movie Database – 1992 TV movie

- Cockpit voice-recorder recording at time of impact

- Accident photos

- A detailed description of the accident

- Errol Morris’ First Person (interview with Denny Fitch)

Coordinates: 42°24′29″N 96°23′02″W / 42.40806°N 96.38389°W

| ||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||