Spectrophotometry

|

|

In chemistry, spectrophotometry is the quantitative measurement of the reflection or transmission properties of a material as a function of wavelength.[1] It is more specific than the general term electromagnetic spectroscopy in that spectrophotometry deals with visible light, near-ultraviolet, and near-infrared, but does not cover time-resolved spectroscopic techniques.

Spectrophotometry uses photometers that can measure a light beam's intensity as a function of its color (wavelength) known as spectrophotometers. Important features of spectrophotometers are spectral bandwidth, (the range of colors it can transmit through the test sample), and the percentage of sample-transmission, and the logarithmic range of sample-absorption and sometimes a percentage of reflectance measurement.

A spectrophotometer is commonly used for the measurement of transmittance or reflectance of solutions, transparent or opaque solids, such as polished glass, or gases. However they can also be designed to measure the diffusivity on any of the listed light ranges that usually cover around 200 nm - 2500 nm using different controls and calibrations.[1] Within these ranges of light, calibrations are needed on the machine using standards that vary in type depending on the wavelength of the photometric determination.[2]

An example of an experiment in which spectrophotometry is used is the determination of the equilibrium constant of a solution. A certain chemical reaction within a solution may occur in a forward and reverse direction where reactants form products and products break down into reactants. At some point, this chemical reaction will reach a point of balance called an equilibrium point. In order to determine the respective concentrations of reactants and products at this point, the light transmittance of the solution can be tested using spectrophotometry. The amount of light that passes through the solution is indicative of the concentration of certain chemicals that do not allow light to pass through.

The use of spectrophotometers spans various scientific fields, such as physics, materials science, chemistry, biochemistry, and molecular biology.[3] They are widely used in many industries including semiconductors, laser and optical manufacturing, printing and forensic examination, as well in laboratories for the study of chemical substances. Ultimately, a spectrophotometer is able to determine, depending on the control or calibration, what substances are present in a target and exactly how much through calculations of observed wavelengths.

History

By 1940 several spectrophotometers were available on the market, but early models could not work in the ultraviolet. Arnold O. Beckman developed an improved version at the National Technical Laboratories Company, later the Beckman Instrument Company and ultimately Beckman Coulter. Models A, B, and C were developed (three units of model C were produced), then the model D, which became DU. All the electronics were contained within the instrument case, and it had a new hydrogen lamp with ultraviolet continuum, and a better monochromator. This instrument was produced from 1941 until 1976 with essentially the same design; over 30,000 were sold. 1941 price was US$723 (far-UV accessories were an option at additional cost). Nobel chemistry laureate Bruce Merrifield said it was "probably the most important instrument ever developed towards the advancement of bioscience."[4]

Design

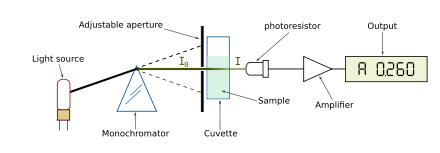

There are two major classes of devices: single beam and double beam. A double beam spectrophotometer compares the light intensity between two light paths, one path containing a reference sample and the other the test sample. A single-beam spectrophotometer measures the relative light intensity of the beam before and after a test sample is inserted. Although comparison measurements from double-beam instruments are easier and more stable, single-beam instruments can have a larger dynamic range and are optically simpler and more compact. Additionally, some specialized instruments, such as spectrophotometers built onto microscopes or telescopes, are single-beam instruments due to practicality.

Historically, spectrophotometers use a monochromator containing a diffraction grating to produce the analytical spectrum. The grating can either be movable or fixed. If a single detector, such as a photomultiplier tube or photodiode is used, the grating can be scanned stepwise so that the detector can measure the light intensity at each wavelength (which will correspond to each "step"). Arrays of detectors, such as charge coupled devices (CCD) or photodiode arrays (PDA) can also be used. In such systems, the grating is fixed and the intensity of each wavelength of light is measured by a different detector in the array. Additionally, most modern mid-infrared spectrophotometers use a Fourier transform technique to acquire the spectral information. The technique is called Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy.

When making transmission measurements, the spectrophotometer quantitatively compares the fraction of light that passes through a reference solution and a test solution, then electronically compares the intensities of the two signals and computes the percentage of transmission of the sample compared to the reference standard. For reflectance measurements, the spectrophotometer quantitatively compares the fraction of light that reflects from the reference and test samples. Light from the source lamp is passed through a monochromator, which diffracts the light into a "rainbow" of wavelengths and outputs narrow bandwidths of this diffracted spectrum through a mechanical slit on the output side of the monochromator. These bandwidths are transmitted through the test sample. Then the photon flux density (watts per metre squared usually) of the transmitted or reflected light is measured with a photodiode, charge coupled device or other light sensor. The transmittance or reflectance value for each wavelength of the test sample is then compared with the transmission or reflectance values from the reference sample. Most instruments will apply a logarithmic function to the linear transmittance ratio to calculate the 'absorbency' of the sample, a value which is proportional to the 'concentration' of the chemical being measured.

In short, the sequence of events in a modern spectrophotometer is as follows:

- The light source is shone into a monochromator and is diffracted into a rainbow and split into two beams and scanned through the sample and the reference solutions.

- Fractions of the incident wavelengths are transmitted through, or reflected from, the sample and the reference.

- The resultant light strikes the photo detector device which compares the relative intensity of the two beams.

- Electronic circuits convert the relative currents into linear transmission percentages and/or absorbance/concentration values.

Many older spectrophotometers must be calibrated by a procedure known as "zeroing," balancing the null current output of the two beams at the detector. The transmission of a reference substance is set as a baseline value, so the transmission of all other substances are recorded relative to the initial "zeroed" substance. The spectrophotometer then converts the transmission ratio into 'absorbency', the concentration of specific components of the test sample [5] relative to the initial substance.[3]

UV-visible spectrophotometry

The most common spectrophotometers are used in the UV and visible regions of the spectrum, and some of these instruments also operate into the near-infrared region as well.

Visible region 400–700 nm spectrophotometry is used extensively in colorimetry science. It is a known fact that it operates best at the range of 0.2-0.8 O.D. Ink manufacturers, printing companies, textiles vendors, and many more, need the data provided through colorimetry. They take readings in the region of every 5–20 nanometers along the visible region, and produce a spectral reflectance curve or a data stream for alternative presentations. These curves can be used to test a new batch of colorant to check if it makes a match to specifications, e.g., ISO printing standards.

Traditional visible region spectrophotometers cannot detect if a colorant or the base material has fluorescence. This can make it difficult to manage color issues if for example one or more of the printing inks is fluorescent. Where a colorant contains fluorescence, a bi-spectral fluorescent spectrophotometer is used. There are two major setups for visual spectrum spectrophotometers, d/8 (spherical) and 0/45. The names are due to the geometry of the light source, observer and interior of the measurement chamber. Scientists use this instrument to measure the amount of compounds in a sample. If the compound is more concentrated more light will be absorbed by the sample; within small ranges, the Beer-Lambert law holds and the absorbance between samples vary with concentration linearly. In the case of printing measurements two alternative settings are commonly used- without/with uv filter to control better the effect of uv brighteners within the paper stock.

Samples are usually prepared in cuvettes; depending on the region of interest, they may be constructed of glass, plastic (visible spectrum region of interest), or quartz (Far UV spectrum region of interest).

Applications

- Estimating dissolved organic carbon concentration

- Specific Ultraviolet Absorption for metric of aromaticity

- Bial's Test for concentration of pentoses

IR spectrophotometry

Spectrophotometers designed for the infrared region are quite different because of the technical requirements of measurement in that region. One major factor is the type of photosensors that are available for different spectral regions, but infrared measurement is also challenging because virtually everything emits IR light as thermal radiation, especially at wavelengths beyond about 5 μm.

Another complication is that quite a few materials such as glass and plastic absorb infrared light, making it incompatible as an optical medium. Ideal optical materials are salts, which do not absorb strongly. Samples for IR spectrophotometry may be smeared between two discs of potassium bromide or ground with potassium bromide and pressed into a pellet. Where aqueous solutions are to be measured, insoluble silver chloride is used to construct the cell.

Spectroradiometers

Spectroradiometers, which operate almost like the visible region spectrophotometers, are designed to measure the spectral density of illuminants. Applications may include evaluation and categorization of lighting for sales by the manufacturer, or for the customers to confirm the lamp they decided to purchase is within their specifications. Components:

- The light source shines onto or through the sample.

- The sample transmits or reflects light.

- The detector detects how much light was reflected from or transmitted through the sample.

- The detector then converts how much light the sample transmitted or reflected into a number.

See also

- Atomic Absorption Spectrophotometry

- Atomic emission spectroscopy

- Inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectroscopy

- Inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry

- Spectroradiometry

- Slope spectroscopy

- Microspectrophotometry

References

- 1 2 Allen, D., Cooksey, C., & Tsai, B. (2010, October 5). Spectrophotometry. Retrieved from http://www.nist.gov/pml/div685/grp03/spectrophotometry.cfm

- ↑ Schwedt, Georg. (1997). The Essential Guide to Analytical Chemistry. (Brooks Haderlie, trans.). Chichester, NY: Wiley. (Original Work Published 1943). pp. 16-17

- 1 2 Rendina, George. Experimental Methods in Modern Biochemistry W. B. Saunders Company: Philadelphia, PA. 1976. pp. 46-55

- ↑ Robert D. Simoni, Robert L. Hill, Martha Vaughan and Herbert Tabor (5 December 2003). "A Classic Instrument: The Beckman DU Spectrophotometer and Its Inventor, Arnold O. Beckman". THE JOURNAL OF BIOLOGICAL CHEMISTRY Vol. 278, No. 49. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ↑ name=Meece

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Spectrophotometry. |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||