Enthalpy

| Thermodynamics | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

The classical Carnot heat engine | ||||||||||||

|

Branches |

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Book:Thermodynamics | ||||||||||||

Enthalpy is a measure of energy in a thermodynamic system. It includes the internal energy, which is the energy required to create a system, and the amount of energy required to make room for it by displacing its environment and establishing its volume and pressure.[1]

Enthalpy is defined as a state function that depends only on the prevailing equilibrium state identified by the variables internal energy, pressure, and volume. It is an extensive quantity. The unit of measurement for enthalpy in the International System of Units (SI) is the joule, but other historical, conventional units are still in use, such as the British thermal unit and the calorie.

The enthalpy is the preferred expression of system energy changes in many chemical, biological, and physical measurements at constant pressure, because it simplifies the description of energy transfer. At constant pressure, the enthalpy change equals the energy transferred from the environment through heating or work other than expansion work.

The total enthalpy, H, of a system cannot be measured directly. The same situation exists in classical mechanics: only a change or difference in energy carries physical meaning. Enthalpy itself is a thermodynamic potential, so in order to measure the enthalpy of a system, we must refer to a defined reference point; therefore what we measure is the change in enthalpy, ΔH. The ΔH is a positive change in endothermic reactions, and negative in heat-releasing exothermic processes.

For processes under constant pressure, ΔH is equal to the change in the internal energy of the system, plus the pressure-volume work that the system has done on its surroundings.[2] This means that the change in enthalpy under such conditions is the heat absorbed (or released) by the material through a chemical reaction or by external heat transfer. Enthalpies for chemical substances at constant pressure assume standard state: most commonly 1 bar pressure. Standard state does not, strictly speaking, specify a temperature (see standard state), but expressions for enthalpy generally reference the standard heat of formation at 25 °C.

Enthalpy of ideal gases and incompressible solids and liquids does not depend on pressure, unlike entropy and Gibbs energy. Real materials at common temperatures and pressures usually closely approximate this behavior, which greatly simplifies enthalpy calculation and use in practical designs and analyses.

Origins

The word enthalpy is based on the Greek enthalpein (ἐνθάλπειν), which means "to warm in".[3] It comes from the Classical Greek prefix ἐν- en-, meaning "to put into", and the verb θάλπειν thalpein, meaning "to heat". The word enthalpy is often incorrectly attributed to Benoît Paul Émile Clapeyron and Rudolf Clausius through the 1850 publication of their Clausius–Clapeyron relation. This misconception was popularized by the 1927 publication of The Mollier Steam Tables and Diagrams. However, neither the concept, the word, nor the symbol for enthalpy existed until well after Clapeyron's death.

The earliest writings to contain the concept of enthalpy did not appear until 1875,[4] when Josiah Willard Gibbs introduced "a heat function for constant pressure". However, Gibbs did not use the word "enthalpy" in his writings.[note 1]

The actual word first appears in the scientific literature in a 1909 publication by J. P. Dalton. According to that publication, Heike Kamerlingh Onnes (1853–1926) actually coined the word.[5]

Over the years, many different symbols were used to denote enthalpy. It was not until 1922 that Alfred W. Porter proposed the symbol "H" as the accepted standard,[6] thus finalizing the terminology still in use today.

Formal definition

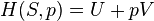

The enthalpy of a homogeneous system is defined as[7][8]

where

- H is the enthalpy of the system,

- U is the internal energy of the system,

- p is the pressure of the system,

- V is the volume of the system.

The enthalpy is an extensive property. This means that, for homogeneous systems, the enthalpy is proportional to the size of the system. It is convenient to introduce the specific enthalpy h = H/m, where m is the mass of the system, or the molar enthalpy Hm = H/n, where n is the number of moles (h and Hm are intensive properties). For inhomogeneous systems the enthalpy is the sum of the enthalpies of the composing subsystems:

where the label k refers to the various subsystems. In case of continuously varying p, T, and/or composition, the summation becomes an integral:

where ρ is the density.

The enthalpy of homogeneous systems can be viewed as function H(S,p) of the entropy S and the pressure p, and a differential relation for it can be derived as follows. We start from the first law of thermodynamics for closed systems for an infinitesimal process:

Here, δQ is a small amount of heat added to the system, and δW a small amount of work performed by the system. In a homogeneous system only reversible processes can take place, so the second law of thermodynamics gives δQ = T dS, with T the absolute temperature of the system. Furthermore, if only pV work is done, δW = p dV. As a result,

Adding d(pV) to both sides of this expression gives

or

So

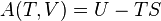

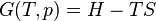

Other expressions

The above expression of dH in terms of entropy and pressure may be unfamiliar to some readers. However, there are expressions in terms of more familiar variables such as temperature and pressure:[9][10]

Here Cp is the heat capacity at constant pressure and α is the coefficient of (cubic) thermal expansion:

With this expression one can, in principle, determine the enthalpy if Cp and V are known as functions of p and T.

Notice that for an ideal gas,  ,[note 2] so that

,[note 2] so that

In a more general form, the first law describes the internal energy with additional terms involving the chemical potential and the number of particles of various types. The differential statement for dH then becomes

where μi is the chemical potential per particle for an i-type particle, and Ni is the number of such particles. The last term can also be written as μi dni (with dni the number of moles of component i added to the system and, in this case, μi the molar chemical potential) or as μi dmi (with dmi the mass of component i added to the system and, in this case, μi the specific chemical potential).

Physical interpretation

The U term can be interpreted as the energy required to create the system, and the pV term as the energy that would be required to "make room" for the system if the pressure of the environment remained constant. When a system, for example, n moles of a gas of volume V at pressure p and temperature T, is created or brought to its present state from absolute zero, energy must be supplied equal to its internal energy U plus pV, where pV is the work done in pushing against the ambient (atmospheric) pressure.

In basic physics and statistical mechanics it may be more interesting to study the internal properties of the system and therefore the internal energy is used.[11][12] In basic chemistry, experiments are often conducted at constant atmospheric pressure, and the pressure-volume work represents an energy exchange with the atmosphere that cannot be accessed or controlled, so that ΔH is the expression chosen for the heat of reaction.

Relationship to heat

In order to discuss the relation between the enthalpy increase and heat supply, we return to the first law for closed systems: dU = δQ − δW. We apply it to the special case with a uniform pressure at the surface. In this case the work term can be split into two contributions, the so-called pV work, given by p dV (where here p is the pressure at the surface, dV is the increase of the volume of the system) and all other types of work δW', such as by a shaft or by electromagnetic interaction. So we write δW = p dV + δW'. In this case the first law reads:

or

From this relation we see that the increase in enthalpy of a system is equal to the added heat:

provided that the system is under constant pressure (dp = 0) and that the only work done by the system is expansion work (δW = 0).[13]

Applications

In thermodynamics, one can calculate enthalpy by determining the requirements for creating a system from "nothingness"; the mechanical work required, pV, differs based upon the conditions that obtain during the creation of the thermodynamic system.

Energy must be supplied to remove particles from the surroundings to make space for the creation of the system, assuming that the pressure p remains constant; this is the pV term. The supplied energy must also provide the change in internal energy, U, which includes activation energies, ionization energies, mixing energies, vaporization energies, chemical bond energies, and so forth. Together, these constitute the change in the enthalpy U + pV. For systems at constant pressure, with no external work done other than the pV work, the change in enthalpy is the heat received by the system.

For a simple system, with a constant number of particles, the difference in enthalpy is the maximum amount of thermal energy derivable from a thermodynamic process in which the pressure is held constant.

Heat of reaction

The total enthalpy of a system cannot be measured directly, the enthalpy change of a system is measured instead. Enthalpy change is defined by the following equation:

where

is the "enthalpy change",

is the "enthalpy change", is the final enthalpy of the system (in a chemical reaction, the enthalpy of the products),

is the final enthalpy of the system (in a chemical reaction, the enthalpy of the products), is the initial enthalpy of the system (in a chemical reaction, the enthalpy of the reactants).

is the initial enthalpy of the system (in a chemical reaction, the enthalpy of the reactants).

For an exothermic reaction at constant pressure, the system's change in enthalpy equals the energy released in the reaction, including the energy retained in the system and lost through expansion against its surroundings. In a similar manner, for an endothermic reaction, the system's change in enthalpy is equal to the energy absorbed in the reaction, including the energy lost by the system and gained from compression from its surroundings. A relatively easy way to determine whether or not a reaction is exothermic or endothermic is to determine the sign of ΔH. If ΔH is positive, the reaction is endothermic, that is heat is absorbed by the system due to the products of the reaction having a greater enthalpy than the reactants. On the other hand if ΔH is negative, the reaction is exothermic, that is the overall decrease in enthalpy is achieved by the generation of heat.

Specific enthalpy

The specific enthalpy of a uniform system is defined as h = H/m where m is the mass of the system. The SI unit for specific enthalpy is joule per kilogram. It can be expressed in other specific quantities by h = u + pv, where u is the specific internal energy, p is the pressure, and v is specific volume, which is equal to 1/ρ, where ρ is the density.

Enthalpy changes

An enthalpy change describes the change in enthalpy observed in the constituents of a thermodynamic system when undergoing a transformation or chemical reaction. It is the difference between the enthalpy after the process has completed, i.e. the enthalpy of the products, and the initial enthalpy of the system, i.e. the reactants. These processes are reversible and the enthalpy for the reverse process is the negative value of the forward change.

A common standard enthalpy change is the enthalpy of formation, which has been determined for a large number of substances. Enthalpy changes are routinely measured and compiled in chemical and physical reference works, such as the CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics. The following is a selection of enthalpy changes commonly recognized in thermodynamics.

When used in these recognized terms the qualifier change is usually dropped and the property is simply termed enthalpy of 'process'. Since these properties are often used as reference values it is very common to quote them for a standardized set of environmental parameters, or standard conditions, including:

- A temperature of 25 °C or 298 K,

- A pressure of one atmosphere (1 atm or 101.325 kPa),

- A concentration of 1.0 M when the element or compound is present in solution,

- Elements or compounds in their normal physical states, i.e. standard state.

For such standardized values the name of the enthalpy is commonly prefixed with the term standard, e.g. standard enthalpy of formation.

Chemical properties:

- Enthalpy of reaction, defined as the enthalpy change observed in a constituent of a thermodynamic system when one mole of substance reacts completely.

- Enthalpy of formation, defined as the enthalpy change observed in a constituent of a thermodynamic system when one mole of a compound is formed from its elementary antecedents.

- Enthalpy of combustion, defined as the enthalpy change observed in a constituent of a thermodynamic system when one mole of a substance burns completely with oxygen.

- Enthalpy of hydrogenation, defined as the enthalpy change observed in a constituent of a thermodynamic system when one mole of an unsaturated compound reacts completely with an excess of hydrogen to form a saturated compound.

- Enthalpy of atomization, defined as the enthalpy change required to atomize one mole of compound completely.

- Enthalpy of neutralization, defined as the enthalpy change observed in a constituent of a thermodynamic system when one mole of water is formed when an acid and a base react.

- Standard Enthalpy of solution, defined as the enthalpy change observed in a constituent of a thermodynamic system when one mole of a solute is dissolved completely in an excess of solvent, so that the solution is at infinite dilution.

- Standard enthalpy of Denaturation (biochemistry), defined as the enthalpy change required to denature one mole of compound.

- Enthalpy of hydration, defined as the enthalpy change observed when one mole of gaseous ions are completely dissolved in water forming one mole of aqueous ions.

Physical properties:

- Enthalpy of fusion, defined as the enthalpy change required to completely change the state of one mole of substance between solid and liquid states.

- Enthalpy of vaporization, defined as the enthalpy change required to completely change the state of one mole of substance between liquid and gaseous states.

- Enthalpy of sublimation, defined as the enthalpy change required to completely change the state of one mole of substance between solid and gaseous states.

- Lattice enthalpy, defined as the energy required to separate one mole of an ionic compound into separated gaseous ions to an infinite distance apart (meaning no force of attraction).

- Enthalpy of mixing, defined as the enthalpy change upon mixing of two (non-reacting) chemical substances.

Open systems

In thermodynamic open systems, matter may flow in and out of the system boundaries. The first law of thermodynamics for open systems states: The increase in the internal energy of a system is equal to the amount of energy added to the system by matter flowing in and by heating, minus the amount lost by matter flowing out and in the form of work done by the system:

where  is the average internal energy entering the system, and

is the average internal energy entering the system, and  is the average internal energy leaving the system.

is the average internal energy leaving the system.

The region of space enclosed by the boundaries if the open system is usually called a control volume, and it may or may not correspond to physical walls. If we choose the shape of the control volume such that all flow in or out occurs perpendicular to its surface, then the flow of matter into the system performs work as if it were a piston of fluid pushing mass into the system, and the system performs work on the flow of matter out as if it were driving a piston of fluid. There are then two types of work performed: flow work described above, which is performed on the fluid (this is also often called pV work), and shaft work, which may be performed on some mechanical device.

These two types of work are expressed in the equation

Substitution into the equation above for the control volume cv yields:

The definition of enthalpy,  , permits us to use this thermodynamic potential to account for both internal energy and

, permits us to use this thermodynamic potential to account for both internal energy and  work in fluids for open systems:

work in fluids for open systems:

If we allow also the system boundary to move (e.g. due to moving pistons), we get a rather general form of the first law for open systems.[14] In terms of time derivatives it reads:

with sums over the various places k where heat is supplied, matter flows into the system, and boundaries are moving. The  terms represent enthalpy flows, which can be written as

terms represent enthalpy flows, which can be written as

with  the mass flow and

the mass flow and  the molar flow at position k respectively. The term dVk/dt represents the rate of change of the system volume at position k that results in pV power done by the system. The parameter P represents all other forms of power done by the system such as shaft power, but it can also be e.g. electric power produced by an electrical power plant.

the molar flow at position k respectively. The term dVk/dt represents the rate of change of the system volume at position k that results in pV power done by the system. The parameter P represents all other forms of power done by the system such as shaft power, but it can also be e.g. electric power produced by an electrical power plant.

Note that the previous expression holds true only if the kinetic energy flow rate is conserved between system inlet and outlet. Otherwise, it has to be included in the enthalpy balance. During steady-state operation of a device (see turbine, pump, and engine), the average dU/dt may be set equal to zero. This yields a useful expression for the average power generation for these devices in the absence of chemical reactions:

where the angle brackets denote time averages. The technical importance of the enthalpy is directly related to its presence in the first law for open systems, as formulated above.

Diagrams

Nowadays the enthalpy values of important substances can be obtained using commercial software. Practically all relevant material properties can be obtained either in tabular or in graphical form. There are many types of diagrams, such as h–T diagrams, which give the specific enthalpy as function of temperature for various pressures, and h–p diagrams, which give h as function of p for various T. One of the most common diagrams is the temperature–entropy diagram (T–s-diagram). It gives the melting curve and saturated liquid and vapor values together with isobars and isenthalps. These diagrams are powerful tools in the hands of the thermal engineer.

Some basic applications

The points a through h in the figure play a role in the discussion in this section.

- a T = 300 K, p = 1 bar, s = 6.85 kJ/(kgK), h = 461 kJ/kg;

- b T = 380 K, p = 2 bar, s = 6.85 kJ/(kgK), h = 530 kJ/kg;

- c T = 300 K, p = 200 bar, s = 5.16 kJ/(kgK), h = 430 kJ/kg;

- d T = 270 K, p = 1 bar, s = 6.79 kJ/(kgK), h = 430 kJ/kg;

- e T = 108 K, p = 13 bar, s = 3.55 kJ/(kgK), h = 100 kJ/kg (saturated liquid at 13 bar);

- f T = 77.2 K, p = 1 bar, s = 3.75 kJ/(kgK), h = 100 kJ/kg;

- g T = 77.2 K, p = 1 bar, s = 2.83 kJ/(kgK), h = 28 kJ/kg (saturated liquid at 1 bar);

- h T = 77.2 K, p = 1 bar, s = 5.41 kJ/(kgK), h =230 kJ/kg (saturated gas at 1 bar);

Throttling

.

.One of the simple applications of the concept of enthalpy is the so-called throttling process, also known as Joule-Thomson expansion. It concerns a steady adiabatic flow of a fluid through a flow resistance (valve, porous plug, or any other type of flow resistance) as shown in the figure. This process is very important, since it is at the heart of domestic refrigerators, where it is responsible for the temperature drop between ambient temperature and the interior of the refrigerator. It is also the final stage in many types of liquefiers.

In the first law for open systems (see above) applied to the system, all terms are zero, except the terms for the enthalpy flow. Hence

Since the mass flow is constant, the specific enthalpies at the two sides of the flow resistance are the same:

that is, the enthalpy per unit mass does not change during the throttling. The consequences of this relation can be demonstrated using the T–s diagram above. Point c is at 200 bar and room temperature (300 K). A Joule–Thomson expansion from 200 bar to 1 bar follows a curve of constant enthalpy of roughly 425 kJ/kg (not shown in the diagram) lying between the 400 and 450 kJ/kg isenthalps and ends in point d, which is at a temperature of about 270 K. Hence the expansion from 200 bar to 1 bar cools nitrogen from 300 K to 270 K. In the valve, there is a lot of friction, and a lot of entropy is produced, but still the final temperature is below the starting value!

Point e is chosen so that it is on the saturated liquid line with h = 100 kJ/kg. It corresponds roughly with p = 13 bar and T = 108 K. Throttling from this point to a pressure of 1 bar ends in the two-phase region (point f). This means that a mixture of gas and liquid leaves the throttling valve. Since the enthalpy is an extensive parameter, the enthalpy in f (hf) is equal to the enthalpy in g (hg) multiplied with the liquid fraction in f (xf) plus the enthalpy in h (hh) multiplied with the gas fraction in f (1 − xf). So

With numbers: 100 = xf 28 + (1 − xf)230, so xf = 0.64. This means that the mass fraction of the liquid in the liquid–gas mixture that leaves the throttling valve is 64%.

Compressors

. A power P is applied and a heat flow

. A power P is applied and a heat flow  is released to the surroundings at ambient temperature Ta.

is released to the surroundings at ambient temperature Ta.A power P is applied e.g. as electrical power. If the compression is adiabatic, the gas temperature goes up. In the reversible case it would be at constant entropy, which corresponds with a vertical line in the T–s diagram. For example, compressing nitrogen from 1 bar (point a) to 2 bar (point b) would result in a temperature increase from 300 K to 380 K. In order to let the compressed gas exit at ambient temperature Ta, heat exchange, e.g. by cooling water, is necessary. In the ideal case the compression is isothermal. The average heat flow to the surroundings is  . Since the system is in the steady state the first law gives

. Since the system is in the steady state the first law gives

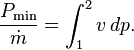

The minimal power needed for the compression is realized if the compression is reversible. In that case the second law of thermodynamics for open systems gives

Eliminating  gives for the minimal power

gives for the minimal power

For example, compressing 1 kg of nitrogen from 1 bar to 200 bar costs at least (hc − ha) − Ta(sc − sa). With the data, obtained with the T–s diagram, we find a value of (430 − 461) − 300 (5.16 − 6.85) = 476 kJ/kg.

The relation for the power can be further simplified by writing it as

With dh = T ds + v dp, this results in the final relation

See also

- Standard enthalpy change of formation (data table)

- Calorimetry

- Calorimeter

- Departure function

- Hess's law

- Isenthalpic process

- Stagnation enthalpy

- Thermodynamic databases for pure substances

- Entropy

Notes

References

- ↑ Mark W. Zemansky (1968), Heat and Thermodynamics, Chapter 11 (5th edition) page 275, McGraw Hill, New York.

- ↑ G.J. Van Wylen and R.E. Sonntag (1985), Fundamentals of Classical Thermodynamics, Section 5.5 (3rd edition), John Wiley & Sons Inc. New York. ISBN 0-471-82933-1

- ↑ "ἐνθάλπω". A Greek–English Lexicon.

- ↑ Henderson, Douglas; Eyring, Henry; Jost, Wilhelm (1967). Physical Chemistry: An Advanced Treatise. Academic Press. p. 29.

- ↑ Laidler, Keith (1995). The World of Physical Chemistry. Oxford University Press. p. 110.

- ↑ Howard, Irmgard (2002). "H Is for Enthalpy, Thanks to Heike Kamerlingh Onnes and Alfred W. Porter". Journal of Chemical Education (ACS Publications) 79 (6): 697. Bibcode:2002JChEd..79..697H. doi:10.1021/ed079p697.

- ↑ E.A. Guggenheim, Thermodynamics, North-Holland Publishing Company, Amsterdam, 1959

- ↑ Zumdahl, Steven S. (2008). "Thermochemistry". Chemistry. Cengage Learning. p. 243. ISBN 978-0-547-12532-9.

- ↑ Guggenheim, p. 88

- ↑ M. J. Moran and H. N. Shapiro "Fundamentals of Engineering Thermodynamics" 5th edition, (2006) John Wiley & Sons, Inc., p. 511.

- ↑ F. Reif Statistical physics McGraw-Hill, London (1967)

- ↑ C. Kittel and H. Kroemer Thermal physics Freeman London (1980)

- ↑ Ebbing, Darrel & Gammon, Steven (2010). General Chemistry. Cengage Learning. p. 231. ISBN 978-0-538-49752-7.

- ↑ M. J. Moran and H. N. Shapiro "Fundamentals of Engineering Thermodynamics" 5th edition, (2006) John Wiley & Sons, Inc., p. 129.

- ↑ Figure composed with data obtained with RefProp, NIST Standard Reference Database 23.

Bibliography

- J.P. Dalton "Researches on the Joule-Kelvin effect, especially at low temperatures. I. Calculations for hydrogen", KNAW Proceedings 11 pp. 863-873 (1909)

- Haase, R. In Physical Chemistry: An Advanced Treatise; Jost, W., Ed.; Academic: New York, 1971; p 29.

- Gibbs, J. W. In The Collected Works of J. Willard Gibbs, Vol. I; Yale University Press: New Haven, Connecticut, reprinted 1948; p 88.

- I.K. Howard "H Is for Enthalpy, Thanks to Heike Kamerlingh Onnes and Alfred W. Porter", Journal of Chemical Education 79 pp. 697-698 (2002)

- Laidler, K. The World of Physical Chemistry; Oxford University Press: Oxford, 1995; p 110.

- C. Kittel, H. Kroemer In Thermal Physics; S. R Furphy and Company, New York, 1980; p246

- DeHoff, R. Thermodynamics in Materials Science: 2nd ed.; Taylor and Francis Group, New York, 2006.

External links

- Enthalpy - Eric Weisstein's World of Physics

- Enthalpy - Georgia State University

- Enthalpy example calculations - Texas A&M University Chemistry Department