Spatial contextual awareness

Spatial contextual awareness consociates contextual information such as an individual’s or sensor’s location, activity, the time of day, and proximity to other people or objects and devices.[1] It is also defined as the relationship between and synthesis of information garnered from the spatial environment, a cognitive agent, and a cartographic map. The spatial environment is the physical space in which the orientation or wayfinding task is to be conducted; the cognitive agent is the person or entity charged with completing a task; and the map is the representation of the environment which is used as a tool to complete the task.[2]

An incomplete view of spatial contextual awareness would render it as simply a contributor to or an element of contextual awareness – that which specifies a point location on the earth. This narrow definition omits the individual cognitive and computational functions involved in a complex geographic system. Rather than defining the myriad of potential factors contributing to context, spatial contextual awareness defined in terms of cognitive processes permits a unique, user-centered perspective in which “conceptualizations imbue spatial structures with meaning.”[2]

Context awareness, geographic awareness, and ubiquitous cartography or Ubiquitous Geographic Information (UBGI) all contribute to the understanding of spatial contextual awareness. They are also key elements in a map-based, location-based service, or LBS. In cases in which the user interface for the LBS is a map, cartographic design challenges must be addressed in order to effectively communicate the spatial context to the user.

Spatial contextual awareness can describe present context – the environment of the user at the present time and location, or that of a future context – where the user wants to go and what may be of interest to them in the approaching spatial environment. Some location-based services are proactive systems which can anticipate future context.[3] Augmented reality is an application which guides a user through present and into future context by displaying spatial contextual information in their visual system as they traverse through real space.[4]

Numerous examples of LBS applications exist which require the ability to leverage spatial contextual awareness. These applications are in demand by the general public and are examples of how maps are being used by individuals to help better understand the world and make daily decisions.[5]

Context awareness

Context awareness originated as a term from ubiquitous computing or as so-called pervasive computing which sought to deal with linking changes in the environment with computer systems, which are otherwise static.[6]

Context is defined in multiple ways, most often with location as the cornerstone. One source defines it as “location and the identity of nearby people and objects.” Another describes it as “location, identity, environment and time”.[7] Yet some definitions recognize context awareness as being more inclusive than location.

Dey[8] took this broader approach: “context is any information that can be used to characterize the situation of an entity, where entity means a person, place, or object, which is relevant to the interaction between a user and an application, including the user and the applications themselves.” The same author defined a system “to be context-aware if it uses context to provide relevant information and/or services to the user, in which the relevancy depends on the user’s task”.[8]

The concept of relevancy is described in the following definition of context awareness: “the set of environmental states and settings that either determines an application’s behavior or in which an application event occurs and is interesting to the user”.[1] Different levels of context, in terms of low and high level have also been outlined. Low-level contexts consist of time, location, network bandwidth and orientation. A high-level context consists of the user’s current activity and social context.[1]

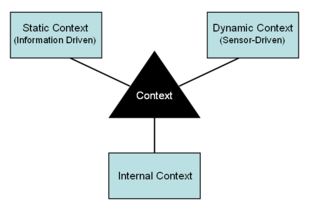

A three-level model of context awareness (Figure 1) includes the changeable nature of the environment by differentiating between the contributions of static, dynamic, and internal context:[9]

- Static context – stored digital geographic information which could impact the user’s environment

- Dynamic context – information on the changeable aspects of the user’s environment obtained by sensors/info services and provided in real time (e.g. weather forecasts, traffic reports)

- Internal context – user information, to include personal preferences, location, speed, and orientation

Static content is driven by stored information while dynamic content is provided and updated by sensors.

Context categories for mobile maps have been identified through pilot user tests. The categories in Table 1 were deemed useful for mobile map services:[10]

| General context categories | Context categories for mobile maps | Features |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Geographic awareness

Geographic awareness, another term for spatial contextual awareness, clarifies the spatial and geographic aspects of context. Being more than simply present location, it must also include other dimensions and their interdependencies. Figure 2 shows Li’s[9] components of context awareness and overlays them on multiple geographic reference systems. To be effective, an LBS application must be able to operate in a heterogeneous space which includes different reference systems. A user of a LBS must be able to seamlessly convert from a Euclidean space (Cartesian Reference Space), to a Linear Reference Space (LRS), to indoor space (to include perhaps the floor, wing, hallway, and room number).[11]

Ubiquitous geographic information (UBGI)/Ubiquitous cartography

Ubiquitous geographic information (UBGI) is geographic information which is provided at any time and any place to users or systems through communication devices. Critical to the understanding of UBGI is that the information provided is based on the context of the user. UBGI is more than data. It includes a set of concepts, practices and standards for spatial and geographic information and processing for applications accessible for use by the general public.[11]

UBGI must also take into account the situation and goals of the user, or cognitive agent. For that purpose, ubiquitous computing concepts employ sensors to collect data on the user’s location as well as environmental parameters.[2]

Ubiquitous cartography is “the ability for users to create and use maps in any place and at any time to resolve geospatial problems”.[12] The users and creators of these maps are more than just highly trained geographers and cartographers, but include the average citizen. In contrast to the accused elitism of the GIS community in the early 80’s when many advocated for separate technology because geospatial information was different and unattainable to common users or systems, today’s goal of ubiquity is to make the user experience with GIS-enabled devices intuitive and simple to use.[13] These devices and other multimedia cartography tools are playing a major role in the effort to get “maps out” to the general public and end the inexcusable practice of perfecting maps as a visualization form only for expert map users operating highly specialized Geographic Information Systems.[5]

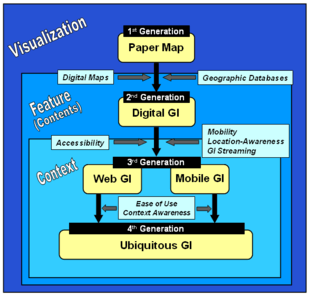

The “ease-of-use” objective of ubiquitous cartography can be seen as the fourth generation in the evolution of geographic information. UBGI was preceded by easily accessible of internet maps and the addition of contextual information of LBS and mobile mapping. Digital geographic information was an essential precursor to accessible and mobile maps and these advancements are all an outgrowth of the first generation of paper maps and the effort to better represent and visualize the world (Fig. 3).[11]

Location-based services (LBS)

A location-based service (LBS) is an information and entertainment service, accessible with mobile devices through the mobile network and utilizing the ability to make use of the geographical position of the mobile device.[14]

LBS services can be used in a variety of contexts, such as health, work, personal life, etc. LBS services include services to identify a location of a person or object, such as discovering the nearest banking cash machine or the whereabouts of a friend or employee. LBS services include parcel tracking and vehicle tracking services. LBS can include mobile commerce when taking the form of coupons or advertising directed at customers based on their current location. They include personalized weather services and even location-based games. They are an example of telecommunication convergence.[14]

Location Based Services have the ability to exploit knowledge about the location of a user or an information device. Whether the output of the device is a simple text message or an interactive graphic map, the user and the user’s location are in some way incorporated into the overall system.[12]

Other distinguishing characteristics of LBS include:[7]

- Usually provide personalized services for a user on-the-move

- Based on diverse hardware and software platforms which utilize the internet, GIS, and location-aware devices and telecommunication services

- Receive data from various sources, sensors and systems

- Must integrate and process data in real-time

- Pose unique challenges for visualization due to the fact that the user’s location could be constantly changing

LBS can be used to answer user questions which can be placed into four general categories: location, proximity, navigation, and events. Examples include:[15]

- Where am I? Where is my destination? [location]

- Where is the nearest bus stop or fast food restaurant? [proximity]

- What is the best route to my destination? [navigation]

- Is the latest movie showing at the local theater? [events]

Another category is “measurement” to answer the question, how far away is my destination?[10] This is a routine function of personal automobile navigation devices.

New, innovative ideas continue to add to the types of questions in which LBS can answer for a user. For example, computer vision and object based indexing can be used to both identify an object and assist a user in navigating from the location. Spatial contextual awareness plays a key role in this process as it provides an initial geo-reference of the location while simplifying the object recognition process to a manageable degree.[16] This category of LBS use can be called “identification” and answers the question “What is it?”

Cartographic challenges

Applications which require the use of spatial contextual awareness in LBS are confronted with a multitude of cartographic challenges and decisions. Some of these challenges are due to the small displays of the typical PDA user interface and method of use.[17] Other problems result from the large volume of potentially relevant contextual data as difficult choices need to be made on the most important content to display.[18]

A sampling of some of these challenges are:

- Mobility – A map on a mobile platform is changing quickly to keep up with context changes; limited time to view map information before a change in scene may be required.[19]

- Adaptation – Refers to “the ability of flexible systems to be changed by the user or the system in order to meet specific requirements.” Users must be able to personalize the display to present content adaptable to their sophistication and familiarity of the environment[19]

- Accessibility – “the matching of people’s information and service needs with their needs and preferences in terms of intellectual and sensory engagement with that information or service, and control of it”.[20] A service need could include a driver who cannot take their eyes off the road to study a map display; or a visitor in a foreign country who cannot understand the language of the audible cues of a LBS provider.

- Generalization – “Due to the very small display area of mobile devices mobile maps need to be extremely generalized.” The design should simple, concise and self-evident as possible and should be instantly usable. “This means to lower the information density following the primacy of relevance over completeness”[19]

- Scaling – Map display is typically very small, requiring scaling functions to show enough area and information to be useful, but at a large enough scale to adequately show detail

- Relevance – “Presenting as much info as needed and as little as required”.[18] The information which is “needed” is the content which is effective for the particular spatial context of the user.

- Presentation Form – Multimedia maps provide several display medium options. The option selected should be the one which best generates the user’s mental map. Besides the visual medium of a graphic map with representative symbols, textual and vocal presentations are options to consider.[21]

- Visual Variables – Color is an appropriate primary graphic element when portraying different type or classes of qualitative features.[22] Color can contribute enormously to the usability of products as it assists in differentiating between different screen elements.[23] High contrast, harmoniously matched colors need to be considered for quick perception and to reduce eye fatigue resulting from the radiant screen display[24]

- Metadata – Good metadata provides information to the user on the sources and quality of data being referenced to include reliability, accuracy, and authenticity. More useful and higher quality metadata for multimedia applications is an omnipresent challenge. International standards have been developed for geographic information, however, these “need to be extended and linked to information object metadata standards for photographs, videos, imagery, text, and other elements used by multimedia cartography”.[25]

- Navigation Views – The determination on best map views to aid user navigation. Considerations include: overview maps available at various scales; automatic zoom to larger scale when user is in motion; maintain egocentric map position with north always marked.[26]

Applications

- Google Maps for mobile: Free download to view maps and satellite imagery, determine present location, business search, driving directions, and traffic reports

- Streamspin: Mobile services platform for delivery and receipt of information and services based on subscriber context and metadata.

- Local Location Assistant (Lol@): Prototype of a location-based multimedia service for a Universal Mobile Telecommunications System in which a foreign tourist can take a self-guided tour along a route based on user input and preferences.

- IPointer (Intelligent Spatial Technologies): Based on an augmented reality engine providing a local mobile client search to provide the user with information about their surroundings. Uses location and radial direction to identify a landmark of interest and stream information content.

- Signpost: A location-aware guide utility which uses computer vision technology to track fiducial markers for wide area indoor tracking. Signpost guides conference attendees through the venue with the use of a cell phone.

See also

- Context awareness

- Contextual cueing

- Ubiquitous computing

- Context-aware pervasive systems

- Human-computer interaction

- Location-based service

- Location awareness

- Sense of direction

- Topology

- Augmented reality

- Fiduciary marker

- Spatial ability

References

- 1 2 3 Chen, Guanling, and David Kotz. 2000. A Survey of Context-Aware Mobile Computing Research. Dartmouth Computer Science Technical Report TR2000-381.

- 1 2 3 Freksa, Christian, Alexander Klippel, and Stephan Winter. 2005. A Cognitive Perspective on Spatial Context. Dagstuhl Seminar Proceedings 05491.

- ↑ Mayrhofer, Rene, Harald Radi, and Alois Ferscha. 2003. Recognizing and Predicting Context by Learning from User Behavior. In The International Conference On Advances in Mobile Multimedia (MoMM2003), ed. W. Schreiner, G. Kotsis, A. Ferscha, and K. Ibrahim, volume 171, pages 25–35. Austrian Computer Society (OCG), September 2003.

- ↑ Gartner, Georg. 2007a. Development of Multimedia – Mobile and Ubiquitous. In Multimedia Cartography, ed. William Cartwright, Michael P. Peterson, and Georg Gartner, 51-62. Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg.

- 1 2 Peterson, Michael P. 2007a. Elements of Multimedia Cartography. In Multimedia Cartography, ed. William Cartwright, Michael P. Peterson, and Georg Gartner, 63-73. Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg.

- ↑ Context awareness

- 1 2 Jiang, Bin, and Xiaobai Yao. 2007. Location Based Services and GIS in Perspective. In Location Based Services and TeleCartography, ed. Georg Gartner, William Cartwright, and Michael P. Peterson, 27-45. Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg.

- 1 2 Dey, Anind K. 2001. Understanding and Using Context. Personal and Ubiquitous Computing, Volume 5, 4-7. Springer London.

- 1 2 3 4 Li, Ki-Joune. 2007. Ubiquitous GIS, Part I: Basic Concepts of Ubiquitous GIS, Lecture Slides, Pusan National University.

- 1 2 3 Nivala, Annu-Maaria, and L. Tiina Sarjakoski. 2003. Need for Context-Aware Topographic Maps in Mobile Devices, In ScanGIS'2003 -Proceedings of the 9th Scandinavian Research Conference on Geographical Information Science, June 4–6, Espoo, Finland.

- 1 2 3 4 Hong, Sang-Ki, 2008. Ubiquitous Geographic Information (UBGI) and address standards. ISO Workshop on address standards: Considering the issues related to an international address standard. 25 May 2008. Copenhagen, Denmark.

- 1 2 Gartner, Georg. 2007b. LBS and TeleCartography: About the book. In Location Based Services and TeleCartography, ed. Georg Gartner, William Cartwright, and Michael P. Peterson, 1-11. Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg.

- ↑ Herring, John R. n.d. Ubiquitous Geographic Information: Releasing GI from Its Ivory Tower, Oracle Corporation.

- 1 2 Location based service

- ↑ Reichenbacher, Tumasch. 2001. The World in Your Pocket – Towards a Mobile Cartography. In Proceedings of the 20th International Cartographic Conference, August 6–10, Beijing, China, 4: 2514–2521.

- ↑ Luley, Patrick, Lucas Paletta, Alexander Almer, Mathias Schardt, Josef Ringert, 2007. Geo-Services and Computer Vision for Object Awareness in Mobile System Applications. In Location Based Services and TeleCartography, ed. Georg Gartner, William Cartwright, and Michael P. Peterson, 291-300. Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg.

- ↑ Peterson, Michael P. 2007b. The Internet and Multimedia Cartography. In Multimedia Cartography, ed. William Cartwright, Michael P. Peterson, and Georg Gartner, 35-50. Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg.

- 1 2 Reichenbacher, Tumasch. 2007b. The concept of relevance in mobile maps. In Location Based Services and TeleCartography, ed. Georg Gartner, William Cartwright, and Michael P. Peterson, 231-246. Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg.

- 1 2 3 Reichenbacher, Tumasch. 2007a. Adaptation in mobile and ubiquitous cartography. In Multimedia Cartography, ed. William Cartwright, Michael P. Peterson, and Georg Gartner, 383-397. Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg.

- ↑ Nevile, Liddy, and Martin Ford. 2007. Location and Access: Issues Enabling Accessibility of Information. In Multimedia Cartography, ed. William Cartwright, Michael P. Peterson, and Georg Gartner, 471-485. Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg.

- ↑ Gartner, Georg. and Verena Radoczky. 2007c. Maps and LBS – Supporting wayfinding by cartographic means. In Multimedia Cartography, ed. William Cartwright, Michael P. Peterson, and Georg Gartner, 369-382. Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg.

- ↑ Robinson, Arthur H., Joel L. Morrison, Phillip C. Muehrcke, A. Jon Kimerling, and Stephen C. Guptill. 1995. Elements of Cartography, 381. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- ↑ Furey, Scott, and Kirk Mitchell. 2007. A Real-World implementation of Multimedia Cartography in LBS: The Whereis Mobile Application Suite. In Multimedia Cartography, ed. William Cartwright, Michael P. Peterson, and Georg Gartner, 399-414. Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg.

- ↑ Wintges, Theodor. 2005. Geodata Communication on Personal Digital Assistants (PDA). In Maps and the Internet, ed. Michael P. Peterson, 397-402. Elsevier Ltd.

- ↑ Taylor, D.R. Fraser, and Tracey P. Lauriault. 2007. Future Directions for Multimedia Cartography. In Multimedia Cartography, ed. William Cartwright, Michael P. Peterson, and Georg Gartner, 505-522. Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg.

- ↑ Radoczky, Verena. 2007. How to design a pedestrian navigation system for indoor and outdoor environments. In Location Based Services and TeleCartography, ed. Georg Gartner, William Cartwright, and Michael P. Peterson, 301-316. Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg.