Sparse matrix

|

| |

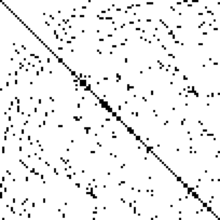

In numerical analysis, a sparse matrix is a matrix in which most of the elements are zero. By contrast, if most of the elements are nonzero, then the matrix is considered dense. The fraction of non-zero elements over the total number of elements (i.e., that can fit into the matrix, say a matrix of dimension of m x n can accommodate m x n total number of elements) in a matrix is called the sparsity (density).

Conceptually, sparsity corresponds to systems which are loosely coupled. Consider a line of balls connected by springs from one to the next: this is a sparse system as only adjacent balls are coupled. By contrast, if the same line of balls had springs connecting each ball to all other balls, the system would correspond to a dense matrix. The concept of sparsity is useful in combinatorics and application areas such as network theory, which have a low density of significant data or connections.

Large sparse matrices often appear in scientific or engineering applications when solving partial differential equations.

When storing and manipulating sparse matrices on a computer, it is beneficial and often necessary to use specialized algorithms and data structures that take advantage of the sparse structure of the matrix. Operations using standard dense-matrix structures and algorithms are slow and inefficient when applied to large sparse matrices as processing and memory are wasted on the zeroes. Sparse data is by nature more easily compressed and thus require significantly less storage. Some very large sparse matrices are infeasible to manipulate using standard dense-matrix algorithms.

Storing a sparse matrix

A matrix is typically stored as a two-dimensional array. Each entry in the array represents an element ai,j of the matrix and is accessed by the two indices i and j. Conventionally, i is the row index, numbered from top to bottom, and j is the column index, numbered from left to right. For an m × n matrix, the amount of memory required to store the matrix in this format is proportional to m × n (disregarding the fact that the dimensions of the matrix also need to be stored).

In the case of a sparse matrix, substantial memory requirement reductions can be realized by storing only the non-zero entries. Depending on the number and distribution of the non-zero entries, different data structures can be used and yield huge savings in memory when compared to the basic approach. The trade-off is that accessing the individual elements becomes more complex and additional structures are needed to be able to recover the original matrix unambiguously.

Formats can be divided into two groups:

- Those that support efficient modification, such as DOK (Dictionary of keys), LIL (List of lists), or COO (Coordinate list). These are typically used to construct the matrices.

- Those that support efficient access and matrix operations, such as CSR (Compressed Sparse Row) or CSC (Compressed Sparse Column).

Dictionary of keys (DOK)

DOK consists of a dictionary that maps (row, column)-pairs to the value of the elements. Elements that are missing from the dictionary are taken to be zero. The format is good for incrementally constructing a sparse matrix in random order, but poor for iterating over non-zero values in lexicographical order. One typically constructs a matrix in this format and then converts to another more efficient format for processing.[1]

List of lists (LIL)

LIL stores one list per row, with each entry containing the column index and the value. Typically, these entries are kept sorted by column index for faster lookup. This is another format good for incremental matrix construction.[2]

Coordinate list (COO)

COO stores a list of (row, column, value) tuples. Ideally, the entries are sorted (by row index, then column index) to improve random access times. This is another format which is good for incremental matrix construction.[3]

Compressed sparse row (CSR, CRS or Yale format)

The compressed sparse row (CSR) or compressed row storage (CRS) format represents a matrices M by three (one-dimensional) arrays, that respectively contain nonzero values, the extents of rows, and column indices. It is similar to COO, but compresses the row indices, hence the name. This format allows fast row access and matrix-vector multiplications (Mx). The CSR format has been in use since at least the mid-1960s, with the first complete description appearing in 1967.[4]

The CSR format stores a sparse m × n matrix M in row form using three (one-dimensional) arrays (A, IA, JA). Let NNZ denote the number of nonzero entries in M. (Note that zero-based indices shall be used here.)

- The array A is of length NNZ and holds all the nonzero entries of M in left-to-right top-to-bottom ("row-major") order.

- The array IA is of length m + 1. It is defined by this recursive definition:

- IA[0] = 0

- IA[i] = IA[i − 1] + (number of nonzero elements on the (i − 1)-th row in the original matrix)

Thus, the first m elements store the index in A of the first nonzero element in each row of M, and the last element IA[m] stores NNZ, the number of elements in A, which can be also thought of as the index in A of first element of a phantom row just beyond the end of the matrix M. The values of the i-th row of the original matrix is read from the elements A[IA[i]] to A[IA[i + 1] − 1] (inclusive on both ends), i.e. from the start of one row to the last index just before the start of the next.[5]

- The third array, JA, contains the column index in M of each element of A and hence is of length NNZ as well.

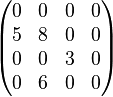

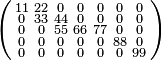

For example, the matrix

is a 4 × 4 matrix with 4 nonzero elements, hence

A = [ 5 8 3 6 ] JA = [ 0 1 2 1 ] IA = [ 0 0 2 3 4 ]

So, in array JA, the element "5" from A has column index 0, "8" and "6" have index 1, and element "3" has index 2.

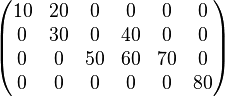

In this case the CSR representation contains 13 entries, compared to 16 in the original matrix. The CSR format saves on memory only when NNZ < (m (n − 1) − 1) / 2. Another example, the matrix

is a 4 × 6 matrix (24 entries) with 8 nonzero elements, so

A = [ 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 ] JA = [ 0 1 1 3 2 3 4 5 ] IA = [ 0 2 4 7 8 ]

The whole is stored as 21 entries.

- IA splits the array A into rows:

(10, 20) (30, 40) (50, 60, 70) (80); - JA aligns values in columns:

(10, 20, ...) (0, 30, 0, 40, ...)(0, 0, 50, 60, 70, 0) (0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 80).

Note that in this format, the first value of IA is always zero and the last is always NNZ, so they are in some sense redundant (although in programming languages where the array length needs to be explicitly stored, NNZ would not be redundant). Nonetheless, this does avoid the need to handle an exceptional case when computing the length of each row, as it guarantees the formula IA[i + 1] − IA[i] works for any row i. Moreover, the memory cost of this redundant storage is likely insignificant for a sufficiently large matrix.

The (old and new) Yale sparse matrix formats are instances of the CSR scheme. The old Yale format works exactly as described above, with three arrays; the new format achieves a further compression by combining IA and JA into a single array.[6]

Compressed sparse column (CSC or CCS)

CSC is similar to CSR except that values are read first by column, a row index is stored for each value, and column pointers are stored. I.e. CSC is (val, row_ind, col_ptr), where val is an array of the (top-to-bottom, then left-to-right) non-zero values of the matrix; row_ind is the row indices corresponding to the values; and, col_ptr is the list of val indexes where each column starts. The name is based on the fact that column index information is compressed relative to the COO format. One typically uses another format (LIL, DOK, COO) for construction. This format is efficient for arithmetic operations, column slicing, and matrix-vector products. See scipy.sparse.csc_matrix.

This is the traditional format for specifying a sparse matrix in MATLAB (via the sparse function).

Special structure

Banded

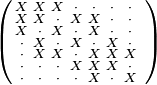

An important special type of sparse matrices is band matrix, defined as follows. The lower bandwidth of a matrix A is the smallest number p such that the entry ai,j vanishes whenever i > j + p. Similarly, the upper bandwidth is the smallest number p such that ai,j = 0 whenever i < j − p (Golub & Van Loan 1996, §1.2.1). For example, a tridiagonal matrix has lower bandwidth 1 and upper bandwidth 1. As another example, the following sparse matrix has lower and upper bandwidth both equal to 3. Notice that zeros are represented with dots for clarity.

Matrices with reasonably small upper and lower bandwidth are known as band matrices and often lend themselves to simpler algorithms than general sparse matrices; or one can sometimes apply dense matrix algorithms and gain efficiency simply by looping over a reduced number of indices.

By rearranging the rows and columns of a matrix A it may be possible to obtain a matrix A′ with a lower bandwidth. A number of algorithms are designed for bandwidth minimization.

Diagonal

A very efficient structure for an extreme case of band matrices, the diagonal matrix, is to store just the entries in the main diagonal as a one-dimensional array, so a diagonal n × n matrix requires only n entries.

Symmetric

A symmetric sparse matrix arises as the adjacency matrix of an undirected graph; it can be stored efficiently as an adjacency list.

Reducing fill-in

The fill-in of a matrix are those entries which change from an initial zero to a non-zero value during the execution of an algorithm. To reduce the memory requirements and the number of arithmetic operations used during an algorithm it is useful to minimize the fill-in by switching rows and columns in the matrix. The symbolic Cholesky decomposition can be used to calculate the worst possible fill-in before doing the actual Cholesky decomposition.

There are other methods than the Cholesky decomposition in use. Orthogonalization methods (such as QR factorization) are common, for example, when solving problems by least squares methods. While the theoretical fill-in is still the same, in practical terms the "false non-zeros" can be different for different methods. And symbolic versions of those algorithms can be used in the same manner as the symbolic Cholesky to compute worst case fill-in.

Solving sparse matrix equations

Both iterative and direct methods exist for sparse matrix solving.

Iterative methods, such as conjugate gradient method and GMRES utilize fast computations of matrix-vector products  , where matrix

, where matrix  is sparse. The use of preconditioners can significantly accelerate convergence of such iterative methods.

is sparse. The use of preconditioners can significantly accelerate convergence of such iterative methods.

See also

References

- Golub, Gene H.; Van Loan, Charles F. (1996). Matrix Computations (3rd ed.). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins. ISBN 978-0-8018-5414-9.

- Stoer, Josef; Bulirsch, Roland (2002). Introduction to Numerical Analysis (3rd ed.). Berlin, New York: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 978-0-387-95452-3.

- Tewarson, Reginald P. (May 1973). Sparse Matrices (Part of the Mathematics in Science & Engineering series). Academic Press Inc. (This book, by a professor at the State University of New York at Stony Book, was the first book exclusively dedicated to Sparse Matrices. Graduate courses using this as a textbook were offered at that University in the early 1980s).

- Bank, Randolph E.; Douglas, Craig C. "Sparse Matrix Multiplication Package" (PDF).

- Pissanetzky, Sergio (1984). Sparse Matrix Technology. Academic Press.

- Snay, Richard A. (1976). "Reducing the profile of sparse symmetric matrices". Bulletin Géodésique 50 (4): 341. doi:10.1007/BF02521587. Also NOAA Technical Memorandum NOS NGS-4, National Geodetic Survey, Rockville, MD.

- ↑ See scipy.org

- ↑ See scipy.org

- ↑ See scipy.org

- ↑ Buluç, Aydın; Fineman, Jeremy T.; Frigo, Matteo; Gilbert, John R.; Leiserson, Charles E. (2009). Parallel sparse matrix-vector and matrix-transpose-vector multiplication using compressed sparse blocks (PDF). ACM Symp. on Parallelism in Algorithms and Architectures. CiteSeerX: 10

.1 ..1 .211 .5256 - ↑ netlib.org

- ↑ Bank, Randolph E.; Douglas, Craig C. (1993), "Sparse Matrix Multiplication Package (SMMP)" (PDF), Advances in Computational Mathematics 1

Further reading

- Gibbs, Norman E.; Poole, William G.; Stockmeyer, Paul K. (1976). "A comparison of several bandwidth and profile reduction algorithms". ACM Transactions on Mathematical Software 2 (4): 322–330. doi:10.1145/355705.355707.

- Gilbert, John R.; Moler, Cleve; Schreiber, Robert (1992). "Sparse matrices in MATLAB: Design and Implementation". SIAM Journal on Matrix Analysis and Applications 13 (1): 333–356. doi:10.1137/0613024.

- Sparse Matrix Algorithms Research at the University of Florida, containing the UF sparse matrix collection.

- SMALL project A EU-funded project on sparse models, algorithms and dictionary learning for large-scale data.

External links

- Oral history interview with Harry M. Markowitz, Charles Babbage Institute, University of Minnesota. Markowitz discusses his development of portfolio theory (for which he received a Nobel Prize in Economics), sparse matrix methods, and his work at the RAND Corporation and elsewhere on simulation software development (including computer language SIMSCRIPT), modeling, and operations research.