Adams–Onís Treaty

| Treaty of Amity, Settlement and Limits between the United States of America, and His Catholic Majesty | |

|---|---|

|

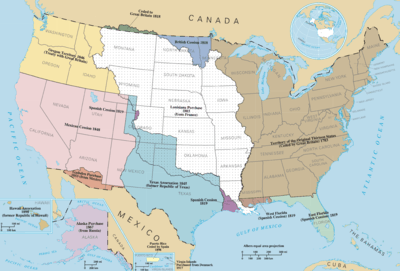

Map showing results of the Adams–Onís Treaty. | |

| Type | Bilateral treaty |

| Context | Territorial cession |

| Signed | February 22, 1819 |

| Location | Washington |

| Effective | February 22, 1821 |

| Expiry | April 14, 1903 |

| Original signatories | |

| Citations | 8 Stat. 252; TS 327; 11 Bevans 528; 3 Miller 3 |

| Terminated by treaty of friendship and general relations of July 3, 1902 (33 Stat. 2105; TS 422; 11 Bevans 628). | |

The Adams–Onís Treaty of 1819,[1] also known as the Transcontinental Treaty,[2] the Florida Purchase Treaty,[3] or the Florida Treaty,[4][5] was a treaty between the United States and Spain in 1819 that ceded Florida to the U.S. and defined the boundary between the U.S. and New Spain. It settled a standing border dispute between the two countries and was considered a triumph of American diplomacy. It came in the midst of increasing tensions related to Spain's territorial boundaries in North America vs. the United States and Great Britain in the aftermath of the American Revolution; and also during the Latin American Wars of Independence. Florida had become a burden to Spain, which could not afford to send settlers or garrisons. Madrid decided to cede the territory to the United States through the Adams–Onís Treaty in exchange for settling the boundary dispute along the Sabine River in Spanish Texas. The treaty established the boundary of U.S. territory and claims through the Rocky Mountains and west to the Pacific Ocean, in exchange for the U.S. paying residents' claims against the Spanish government up to a total of $5,000,000 and relinquishing the US claims on parts of Spanish Texas west of the Sabine River and other Spanish areas, under the terms of the Louisiana Purchase.

History

The Treaty was negotiated by John Quincy Adams, the Secretary of State under U.S. President James Monroe, and the Spanish foreign minister Luis de Onís y González-Vara, during the reign of King Ferdinand VII.[6]

Spain's territories

Spain had long rejected repeated American efforts to purchase Florida. But by 1818, Spain was facing a troubling colonial situation where the cession of Florida made sense. Spain had been exhausted by the Peninsular War in Europe and needed to rebuild its credibility and presence in its colonies. Revolutionaries in Central America and South America were beginning to demand independence. Spain was unwilling to invest further in Florida, encroached on by American settlers, and it worried about the border between New Spain (a large area including today's Mexico, Central America, and much of the current US Western States) and the United States. With minor military presence in Florida, Spain was not able to restrain the Seminole warriors who routinely crossed the border and raided American villages and farms, as well as protected southern slave refugees from slave owners and traders of the southern United States.[7]

By 1819, Spain was forced to negotiate, as it was losing hold on its American empire, with its western territories primed to revolt. While fighting escaped African-American slaves, outlaws, and Native Americans in U.S.-controlled Georgia during the First Seminole War, American General Andrew Jackson had pursued them into Spanish Florida. He attacked and captured forts, such as the so-called "Negro Fort" (an abandoned British fort manned by escaped slaves and Native Americans), in Florida that he thought were assisting the raids into American territory.

To stop the Seminole Indians based in East Florida from raiding Georgia settlements and offering havens for runaway slaves, the U.S. Army led increasingly frequent incursions into Spanish territory. This included the 1817–1818 campaign by Andrew Jackson that became known as the First Seminole War, after which the U.S. effectively controlled East Florida. Secretary of State John Quincy Adams said the US had to take control because Florida had become "a derelict open to the occupancy of every enemy, civilized or savage, of the United States, and serving no other earthly purpose than as a post of annoyance to them."[8] Spain asked for British intervention, but London declined to assist Spain in the negotiations. Some of President James Monroe's cabinet demanded Jackson's immediate dismissal for invading Florida, but Adams realized that his success had given the U.S. a favorable diplomatic position. Adams was able to negotiate very favorable terms.[7]

Louisiana

Spain and the United States had disagreed over the boundaries of the territory of the Louisiana Purchase of 1803. Spain considered it to be at the west bank of the Mississippi River and the city of New Orleans. The United States claimed that the land they bought reached to the Summit of the Rocky Mountains.[9] Eventually the U.S. admitted to claim only as far west as the Sabine River, but Spain insisted that the boundary should be upon the Arroyo Hondo. The disputed region was known as Neutral Ground.

Details of the treaty

The treaty, consisting of 16 articles[10] was signed in Adams' State Department office at Washington,[11] on February 22, 1819, by John Quincy Adams, U.S. Secretary of State, and Luis de Onís, Spanish minister. Ratification was postponed for two years, because Spain wanted to use the treaty as an incentive to keep the United States from giving diplomatic support to the revolutionaries in South America. As soon as the treaty was signed, the U.S. Senate ratified unanimously; but because of Spain's stalling, a new ratification was necessary and this time there were objections. Henry Clay and other Western spokesmen demanded that Spain also give up Texas. This proposal was defeated by the Senate, which ratified the treaty a second time on February 19, 1821 following ratification by Spain on October 24, 1820. Ratifications were exchanged three days later and the treaty was proclaimed on February 22, 1821, two years after the signing.[12]

The Treaty closed the first era of United States expansion by providing for the cession of East Florida under Article 2; the abandonment of the controversy over West Florida under Article 2 (a portion of which had been seized by the United States); and the definition of a boundary with the Spanish province of Mexico, that clearly made Spanish Texas a part of Mexico, under Article 3, thus ending much of the vagueness in the boundary of the Louisiana Purchase. Spain also ceded to the U.S. its claims to the Oregon Country, under Article 3.

The U.S. did not pay Spain for Florida, but instead agreed to pay the legal claims of American citizens against Spain, to a maximum of $5 million, under Article 11.[13] Under Article 12, Pinckney's Treaty of 1795 between the U.S. and Spain was to remain in force. Under Article 15, Spanish goods received exclusive most-favored-nation tariff privileges in the ports at Pensacola and St. Augustine for twelve years.

Under Article 2, the U.S. received ownership of Spanish Florida (British East Florida and West Florida 1763-1783). Under Article 3, the U.S. relinquished its own claims on parts of Texas west of the Sabine River and other Spanish areas.

The Adams–Onís Treaty settled the dispute by defining borders more precisely, roughly granting Florida, the Gulf Coast areas of future Mississippi and Alabama, and western Louisiana to the U.S. while giving to Spain everything west of Louisiana from Texas to California. The new boundary was to be the Sabine River north from the Gulf of Mexico to the 32nd parallel north, then due north to the Red River, west along the Red River to the 100th meridian west, due north to the Arkansas River, west to its headwaters, north to the 42nd parallel north, and finally west along that parallel to the Pacific Ocean.

Informally this has been called the "Step Boundary," although the step-like shape of the boundary was not apparent for several decades — the source of the Arkansas, believed to be near the 42nd parallel, was not known until John C. Frémont located it in the 1840s, hundreds of miles south of the 42nd parallel.

Oregon

The claims of Spain in the Pacific Northwest dated to the papal bull of 1493, which had granted to Spain the rights to colonize the western coast of North America, and to the explorer Vasco Núñez de Balboa in 1513, who claimed all the "South Sea" (the entire Pacific Ocean) and the lands adjoining the Pacific Ocean for the Spanish Crown. To solidify these 250-year-old claims, in the late 18th century Spain established Santa Cruz de Nuca in today's British Columbia and performed "acts of sovereignty" in Alaska. As a result of the Adams–Onís Treaty, the United States acquired the claims of Spain to the Pacific Northwest north of the 42nd parallel.[14]

For the United States, this Treaty (and the Treaty of 1818 with Britain agreeing to joint occupancy of the Pacific Northwest) meant that its claimed territory now extended far west from the Mississippi River to the Pacific Ocean. For Spain, it meant that it kept its colonies in Texas and also kept a buffer zone between its colonies in California and New Mexico and the U.S. territories. Historians consider the Treaty to be a great achievement for the U.S., as time validated Adams's vision that it would allow the U.S. to open trade with the Orient across the Pacific.[15]

Implementation

Washington set up a commission, 1821 to 1824, that handled American claims against Spain. Many notable lawyers, including Daniel Webster and William Wirt, represented claimants before the commission. During its term, the commission examined 1,859 claims arising from over 720 spoliation incidents, and distributed the $5 million in a basically fair manner.[16] The treaty reduced tensions with Spain (and after 1821 Mexico), and allowed budget cutters in Congress to reduce the army budget and reject the plans to modernize and expand the army proposed by Secretary of War John C. Calhoun.

The treaty was honored by both sides, although inaccurate maps from the treaty meant that the boundary between Texas and Oklahoma remained unclear for most of the 19th century. The American boundary was expanded in 1848 by the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo with Mexico.

Later developments

The treaty was ratified by Spain in 1820, and by the United States in 1821 (during the time that Spain and Mexico were engaged in the prolonged Mexican War of Independence). Spain finally recognized the independence of Mexico with the Treaty of Córdoba signed on August 24, 1821. While Mexico was not initially a party to the Adams–Onís Treaty, in 1831 Mexico ratified the treaty by agreeing to the 1828 Treaty of Limits with the U.S.[17]

By the mid-1830s, a controversy developed regarding the border with Texas, during which the United States demonstrated that the Sabine and Neches rivers had been switched on maps, moving the frontier in favor of Mexico. As a consequence, the eastern boundary of Texas was not firmly established until the independence of the Republic of Texas in 1836. It was not agreed upon by the United States and Mexico until the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848, which concluded the Mexican–American War. The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo formalized the cession by Mexico of Alta California and today's American Southwest, except for the territory of the later Gadsden Purchase of 1854.[18]

Another dispute occurred after Texas joined the Union. The treaty stated that the boundary between the French claims on the north and the Spanish claims on the south was Rio Roxo de Natchitoches (Red River) until it reached the 100th meridian, as noted on the John Melish map of 1818. But, the 100th meridian on the Melish map was marked some 90 miles (140 km) east of the true 100th meridian, and the Red River forked about 50 miles (80 km) east of the 100th meridian. Texas claimed the land south of the North Fork, and the United States claimed the land north of the South Fork (later called the Prairie Dog Town Fork Red River). In 1860 Texas organized the area as Greer County. The matter was not settled until a United States Supreme Court ruling in 1896 upheld federal claims to the territory, after which it was added to the Oklahoma Territory.

See also

References

- ↑ Crutchfield, James A.; Moutlon, Candy; Del Bene, Terry. The Settlement of America: An Encyclopedia of Westward Expansion from Jamestown to the Closing of the Frontier. Routledge. p. 51. ISBN 978-1-317-45461-8.

The formal name of the agreement is Treaty of Amity, Settlement, and Limits Between the United States of America and His Catholic Majesty.

- ↑ The Oxford Encyclopedia of American Military and Diplomatic History. OUP USA. January 31, 2013. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-19-975925-5.

- ↑ Danver, Steven L. (May 14, 2013). Encyclopedia of Politics of the American West. SAGE Publications. p. 147. ISBN 978-1-4522-7606-9.

- ↑ Weeks, p.168.

- ↑ A History of British Columbia, p. 90, E.O.S. Scholefield, British Columbia Historical Association, Vancouver, British Columbia 1913

- ↑ Weeks, pp. 170–175.

- 1 2 Weeks

- ↑ Alexander Deconde, A History of American Foreign Policy (1963) p. 127

- ↑ Hämäläinen, Pekka (2008), The Comanche Empire, New Haven: Yale University Press, p. 156, ISBN 978-0-300-12654-9.

- ↑ "Adams-Onís Treaty of 1819". Sons of Dewitt Colony. TexasTexas A&M University,. Archived from the original on April 28, 2015.

- ↑ Adams, John Quincy. "Diary of John Quincy Adams" 31: 44.

- ↑ Deconde, History of American Foreign Policy, p 128

- ↑ The U.S. commission established to adjudicate claims considered some 1,800 claims and agreed that they were collectively worth $5,454,545.13. Since the treaty limited the payment of claims to $5 million, the commission reduced the amount paid out proportionately by 8⅓ percent.

- ↑ Brooks (1939)

- ↑ Howard Jones, Crucible of Power: A History of American Foreign Relations to 1913 (2009), p. 112

- ↑ Cash, Peter Arnold (1999), "The Adams-Onís Treaty Claims Commission: Spoliation and Diplomacy, 1795-1824", DAI (PhD dissertation U. of Memphis 1998) 59 (9), pp. 3611–A. DA9905078 Fulltext: ProQuest Dissertations & Theses.

- ↑ The Border: Adams–Onís Treaty, PBS

- ↑ Brooks (1939) ch 6

This article incorporates material from the Citizendium article "Adams–Onís Treaty", which is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License but not under the GFDL.

Further reading

- Bailey, Hugh C. (1956). "Alabama's Political Leaders and the Acquisition of Florida" (PDF). Florida Historical Quarterly 35 (1): 17–29. ISSN 0015-4113.

- Bemis, Samuel Flagg (1949). John Quincy Adams and the Foundations of American Foreign Policy. New York: A. A. Knopf., the standard history.

- Brooks, Philip Coolidge (1939). Diplomacy and the borderlands: the Adams–Onís Treaty of 1819.

- Weeks, William Earl (1992). John Quincy Adams and American Global Empire. Lexington, Kentucky: University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 0-8131-9058-4..

- Sources

External links

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||