Sound card

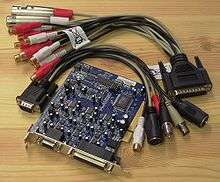

.png) A Sound Blaster Live! Value card, a typical (circa 2000) PCI sound card. | |

| Connects to |

Motherboard via one of:

Line in or out: via one of:

Microphone via one of:

|

|---|---|

| Common manufacturers |

Creative Labs (and subsidiary E-mu Systems) Realtek C-Media MARIAN digital audio electronics M-Audio Turtle Beach ASUS |

A sound card (also known as an audio card) is an internal computer expansion card that facilitates economical input and output of audio signals to and from a computer under control of computer programs. The term sound card is also applied to external audio interfaces that use software to generate sound, as opposed to using hardware inside the PC. Typical uses of sound cards include providing the audio component for multimedia applications such as music composition, editing video or audio, presentation, education and entertainment (games) and video projection.

Sound functionality can also be integrated onto the motherboard, using components similar to plug-in cards. The best plug-in cards, which use better and more expensive components, can achieve higher quality than integrated sound. The integrated sound system is often still referred to as a "sound card". Sound processing hardware is also present on modern video cards with HDMI to output sound along with the video using that connector, previously they used a SPDIF connection to the motherboard or sound card.

General characteristics

Most sound cards use a digital-to-analog converter (DAC), which converts recorded or generated digital data into an analog format. The output signal is connected to an amplifier, headphones, or external device using standard interconnects, such as a TRS phone connector or an RCA connector. If the number and size of connectors is too large for the space on the backplate the connectors will be off-board, typically using a breakout box, an auxiliary backplate, or a panel mounted at the front. More advanced cards usually include more than one sound chip to support higher data rates and multiple simultaneous functionality, for example digital production of synthesized sounds, usually for real-time generation of music and sound effects using minimal data and CPU time.

Digital sound reproduction is usually done with multichannel DACs, which are capable of simultaneous and digital samples at different pitches and volumes, and application of real-time effects such as filtering or deliberate distortion. Multichannel digital sound playback can also be used for music synthesis, when used with a compliance,[1] and even multiple-channel emulation. This approach has become common as manufacturers seek simpler and lower-cost sound cards.

Most sound cards have a line in connector for an input signal from a cassette tape or other sound source that has higher voltage levels than a microphone. The sound card digitizes this signal. The DMAC transfers the samples to the main memory, from where a recording software may write it to the hard disk for storage, editing, or further processing. Another common external connector is the microphone connector, for signals from a microphone or other low-level input device. Input through a microphone jack can be used, for example, by speech recognition or voice over IP applications.

Sound channels and polyphony

An important sound card characteristic is polyphony, which refers to its ability to process and output multiple independent voices or sounds simultaneously. These distinct channels are seen as the number of audio outputs, which may correspond to a speaker configuration such as 2.0 (stereo), 2.1 (stereo and sub woofer), 5.1 (surround), or other configuration. Sometimes, the terms voice and channel are used interchangeably to indicate the degree of polyphony, not the output speaker configuration.

For example, many older sound chips could accommodate three voices, but only one audio channel (i.e., a single mono output) for output, requiring all voices to be mixed together. Later cards, such as the AdLib sound card, had a 9-voice polyphony combined in 1 mono output channel.

For some years, most PC sound cards have had multiple FM synthesis voices (typically 9 or 16) which were usually used for MIDI music. The full capabilities of advanced cards are often not fully used; only one (mono) or two (stereo) voice(s) and channel(s) are usually dedicated to playback of digital sound samples, and playing back more than one digital sound sample usually requires a software downmix at a fixed sampling rate. Modern low-cost integrated soundcards (i.e., those built into motherboards) such as audio codecs like those meeting the AC'97 standard and even some lower-cost expansion sound cards still work this way. These devices may provide more than two sound output channels (typically 5.1 or 7.1 surround sound), but they usually have no actual hardware polyphony for either sound effects or MIDI reproduction – these tasks are performed entirely in software. This is similar to the way inexpensive softmodems perform modem tasks in software rather than in hardware.

Also, in the early days of 'wavetable' sample-based synthesis, some sound card manufacturers advertised polyphony solely on the MIDI capabilities alone. In this case, the card's output channel is irrelevant; typically, the card is only capable of two channels of digital sound. Instead, the polyphony measurement solely applies to the number of MIDI instruments the sound card is capable of producing at one given time.

Today, a sound card providing actual hardware polyphony, regardless of the number of output channels, is typically referred to as a "hardware audio accelerator", although actual voice polyphony is not the sole (or even a necessary) prerequisite, with other aspects such as hardware acceleration of 3D sound, positional audio and real-time DSP effects being more important.

Since digital sound playback has become available and single and provided better performance than synthesis, modern soundcards with hardware polyphony do not actually use DACs with as many channels as voices; instead, they perform voice mixing and effects processing in hardware, eventually performing digital filtering and conversions to and from the frequency domain for applying certain effects, inside a dedicated DSP. The final playback stage is performed by an external (in reference to the DSP chip(s)) DAC with significantly fewer channels than voices (e.g., 8 channels for 7.1 audio, which can be divided among 32, 64 or even 128 voices).

Color codes

Connectors on the sound cards are color-coded as per the PC System Design Guide.[2] They will also have symbols with arrows, holes and soundwaves that are associated with each jack position, the meaning of each is given below:

| Color | Function | Connector | symbol | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pink | Analog microphone audio input. | 3.5 mm minijack | A microphone | |

| Light blue | Analog line level audio input. | 3.5 mm minijack | An arrow going into a circle | |

| Lime green | Analog line level audio output for the main stereo signal (front speakers or headphones). | 3.5 mm minijack | Arrow going out one side of a circle into a wave | |

| Orange | Analog line level audio output for center channel speaker and subwoofer. | 3.5 mm minijack | ||

| Black | Analog line level audio output for surround speakers, typically rear stereo. | 3.5 mm minijack | ||

| Silver/Grey | Analog line level audio output for surround optional side channels. | 3.5 mm minijack | ||

| Brown/Dark | Analog line level audio output for a special panning, 'Right-to-left speaker'. | 3.5 mm minijack | ||

| Gold/Grey | Game port / MIDI | 15 pin D | Arrow going out both sides into waves | |

History of sound cards for the IBM PC architecture

.png)

.png)

.jpg)

Sound cards for computers compatible with the IBM PC were very uncommon until 1988, which left the single internal PC speaker as the only way early PC software could produce sound and music.[3] The speaker hardware was typically limited to square waves, which fit the common nickname of "beeper". The resulting sound was generally described as "beeps and boops". Several companies, most notably Access Software, developed techniques for digital sound reproduction over the PC speaker (see RealSound); the resulting audio, while barely functional, suffered from distorted output and low volume, and usually required all other processing to be stopped while sounds were played. Other home computer models of the 1980s included hardware support for digital sound playback, or music synthesis (or both), leaving the IBM PC at a disadvantage to them when it came to multimedia applications such as music composition or gaming. The initial design and marketing focuses of sound cards for the IBM PC platform were not based on gaming, but rather on specific audio applications such as music composition (AdLib Personal Music System, IBM Music Feature Card, Creative Music System), or on speech synthesis (Digispeech DS201, Covox Speech Thing, Street Electronics Echo).

In 1988 a panel of computer-game CEOs stated at the Consumer Electronics Show that the PC's limited sound capability prevented it from becoming the leading home computer, that it needed a $49–79 sound card with better capability than current products, and that once such hardware was widely installed their companies would support it. Sierra On-Line, which had pioneered supporting EGA and VGA video, and 3 1/2" disks, that year promised to support AdLib, IBM Music Feature, and Roland MT-32 in its games; the cards cost $195 to $600.[4] A 1989 Computer Gaming World survey found that 18 of 25 game companies planned to support AdLib, six Roland and Covox, and seven Creative Music System/Game Blaster.[5]

Hardware manufacturers

One of the first manufacturers of sound cards for the IBM PC was AdLib,[3] which produced a card based on the Yamaha YM3812 sound chip, also known as the OPL2. The AdLib had two modes: A 9-voice mode where each voice could be fully programmed, and a less frequently used "percussion" mode with 3 regular voices producing 5 independent percussion-only voices for a total of 11. (The percussion mode was considered inflexible by most developers; it was used mostly by AdLib's own composition software.)

Creative Labs also marketed a sound card about the same time called the Creative Music System. Although the C/MS had twelve voices to AdLib's nine, and was a stereo card while the AdLib was mono, the basic technology behind it was based on the Philips SAA1099 chip which was essentially a square-wave generator. It sounded much like twelve simultaneous PC speakers would have except for each channel having amplitude control, and failed to sell well, even after Creative renamed it the Game Blaster a year later, and marketed it through RadioShack in the US. The Game Blaster retailed for under $100 and was compatible with many popular games, such as Silpheed.

A large change in the IBM PC compatible sound card market happened when Creative Labs introduced the Sound Blaster card.[3] Recommended by Microsoft to developers creating software based on the Multimedia PC standard,[6] the Sound Blaster cloned the AdLib and added a sound coprocessor for recording and play back of digital audio (likely to have been an Intel microcontroller relabeled by Creative). It was incorrectly called a "DSP" (to suggest it was a digital signal processor), a game port for adding a joystick, and capability to interface to MIDI equipment (using the game port and a special cable). With more features at nearly the same price, and compatibility as well, most buyers chose the Sound Blaster. It eventually outsold the AdLib and dominated the market.

Roland also made sound cards in the late 1980s, most of them being high quality "prosumer" cards, such as the MT-32 and LAPC-I.[3] Roland cards often sold for hundreds of dollars, and sometimes over a thousand. Many games had music written for their cards, such as Silpheed and Police Quest II. The cards were often poor at sound effects such as laughs, but for music were by far the best sound cards available until the mid nineties. Some Roland cards, such as the SCC, and later versions of the MT-32 were made to be less expensive, but their quality was usually drastically poorer than the other Roland cards.

By 1992 one sound card vendor advertised that its product was "Sound Blaster, AdLib, Disney Sound Source and Covox Speech Thing Compatible!".[7] The Sound Blaster line of cards, together with the first inexpensive CD-ROM drives and evolving video technology, ushered in a new era of multimedia computer applications that could play back CD audio, add recorded dialogue to video games, or even reproduce full motion video (albeit at much lower resolutions and quality in early days). The widespread decision to support the Sound Blaster design in multimedia and entertainment titles meant that future sound cards such as Media Vision's Pro Audio Spectrum and the Gravis Ultrasound had to be Sound Blaster compatible if they were to sell well. Until the early 2000s (by which the AC'97 audio standard became more widespread and eventually usurped the SoundBlaster as a standard due to its low cost and integration into many motherboards), Sound Blaster compatibility is a standard that many other sound cards still support to maintain compatibility with many games and applications released.

Industry adoption

When game company Sierra On-Line opted to support add-on music hardware (instead of built-in hardware such as the PC speaker and built-in sound capabilities of the IBM PCjr and Tandy 1000), what could be done with sound and music on the IBM PC changed dramatically. Two of the companies Sierra partnered with were Roland and AdLib, opting to produce in-game music for King's Quest 4 that supported the MT-32 and AdLib Music Synthesizer. The MT-32 had superior output quality, due in part to its method of sound synthesis as well as built-in reverb. Since it was the most sophisticated synthesizer they supported, Sierra chose to use most of the MT-32's custom features and unconventional instrument patches, producing background sound effects (e.g., chirping birds, clopping horse hooves, etc.) before the Sound Blaster brought playing real audio clips to the PC entertainment world. Many game companies also supported the MT-32, but supported the Adlib card as an alternative because of the latter's higher market base. The adoption of the MT-32 led the way for the creation of the MPU-401/Roland Sound Canvas and General MIDI standards as the most common means of playing in-game music until the mid-1990s.

Feature evolution

Early ISA bus soundcards were half-duplex, meaning they couldn't record and play digitized sound simultaneously, mostly due to inferior card hardware (e.g., DSPs). Later, ISA cards like the SoundBlaster AWE series and Plug-and-play Soundblaster clones eventually became full-duplex and supported simultaneous recording and playback, but at the expense of using up two IRQ and DMA channels instead of one, making them no different from having two half-duplex sound cards in terms of configuration. Towards the end of the ISA bus' life, ISA soundcards started taking advantage of IRQ sharing, thus reducing the IRQs needed to one, but still needed two DMA channels. Many PCI bus cards do not have these limitations and are mostly full-duplex. It should also be noted that many modern PCI bus cards also do not require free DMA channels to operate.

Also, throughout the years, soundcards have evolved in terms of digital audio sampling rate (starting from 8-bit 11025 Hz, to 32-bit, 192 kHz that the latest solutions support). Along the way, some cards started offering 'wavetable' sample-based synthesis, which provides superior MIDI synthesis quality relative to the earlier OPL-based solutions, which uses FM-synthesis. Also, some higher end cards started having their own RAM and processor for user-definable sound samples and MIDI instruments as well as to offload audio processing from the CPU.

For years, soundcards had only one or two channels of digital sound (most notably the Sound Blaster series and their compatibles) with the exception of the E-MU card family, the Gravis GF-1 and AMD Interwave, which had hardware support for up to 32 independent channels of digital audio. Early games and MOD-players needing more channels than a card could support had to resort to mixing multiple channels in software. Even today, the tendency is still to mix multiple sound streams in software, except in products specifically intended for gamers or professional musicians, with a sensible difference in price from "software based" products. Also, in the early era of 'wavetable' sample-based synthesis, soundcard companies would also sometimes boast about the card's polyphony capabilities in terms of MIDI synthesis. In this case polyphony solely refers to the count of MIDI notes the card is capable of synthesizing simultaneously at one given time and not the count of digital audio streams the card is capable of handling.

In regards to physical sound output, the number of physical sound channels has also increased. The first soundcard solutions were mono. Stereo sound was introduced in the early 1980s, and quadraphonic sound came in 1989. This was shortly followed by 5.1 channel audio. The latest soundcards support up to 8 physical audio channels in the 7.1 speaker setup.[8]

Crippling of features

Most new soundcards no longer have the audio loopback device commonly called "Stereo Mix"/"Wave out mix"/"Mono Mix"/"What U Hear" that was once very prevalent and that allows users to digitally record speaker output to the microphone input.

Lenovo and other manufacturers fail to implement the chipset feature in hardware, while other manufacturers disable the driver from supporting it. In some cases loopback can be reinstated with driver updates (as in the case of some Dell computers[9]); alternatively software (Total Recorder or "Virtual Audio Cable") can be purchased to enable the functionality. According to Microsoft, the functionality was hidden by default in Windows Vista (to reduce user confusion), but is still available, as long as the underlying sound card drivers and hardware support it.[10] Ultimately, the user can connect the line out directly to the line in (analog hole).

Professional soundcards (audio interfaces)

Professional soundcards are special soundcards optimized for low-latency multichannel sound recording and playback, including studio-grade fidelity. Their drivers usually follow the Audio Stream Input Output protocol for use with professional sound engineering and music software, although ASIO drivers are also available for a range of consumer-grade soundcards.

Professional soundcards are usually described as "audio interfaces", and sometimes have the form of external rack-mountable units using USB, FireWire, or an optical interface, to offer sufficient data rates. The emphasis in these products is, in general, on multiple input and output connectors, direct hardware support for multiple input and output sound channels, as well as higher sampling rates and fidelity as compared to the usual consumer soundcard. In that respect, their role and intended purpose is more similar to a specialized multi-channel data recorder and real-time audio mixer and processor, roles which are possible only to a limited degree with typical consumer soundcards.

On the other hand, certain features of consumer soundcards such as support for environmental audio extensions (EAX), optimization for hardware acceleration in video games, or real-time ambience effects are secondary, nonexistent or even undesirable in professional soundcards, and as such audio interfaces are not recommended for the typical home user.

The typical "consumer-grade" soundcard is intended for generic home, office, and entertainment purposes with an emphasis on playback and casual use, rather than catering to the needs of audio professionals. In response to this, Steinberg (the creators of audio recording and sequencing software, Cubase and Nuendo) developed a protocol that specified the handling of multiple audio inputs and outputs.

In general, consumer grade soundcards impose several restrictions and inconveniences that would be unacceptable to an audio professional. One of a modern soundcard's purposes is to provide an AD/DA converter (analog to digital/digital to analog). However, in professional applications, there is usually a need for enhanced recording (analog to digital) conversion capabilities.

One of the limitations of consumer soundcards is their comparatively large sampling latency; this is the time it takes for the AD Converter to complete conversion of a sound sample and transfer it to the computer's main memory.

Consumer soundcards are also limited in the effective sampling rates and bit depths they can actually manage (compare analog versus digital sound) and have lower numbers of less flexible input channels: professional studio recording use typically requires more than the two channels that consumer soundcards provide, and more accessible connectors, unlike the variable mixture of internal—and sometimes virtual—and external connectors found in consumer-grade soundcards.

Sound devices other than expansion cards

Integrated sound hardware on PC motherboards

In 1984, the first IBM PCjr had a rudimentary 3-voice sound synthesis chip (the SN76489) which was capable of generating three square-wave tones with variable amplitude, and a pseudo-white noise channel that could generate primitive percussion sounds. The Tandy 1000, initially a clone of the PCjr, duplicated this functionality, with the Tandy TL/SL/RL models adding digital sound recording and playback capabilities. Many games during the 1980s that supported the PCjr's video standard (described as "Tandy-compatible", "Tandy graphics", or "TGA") also supported PCjr/Tandy 1000 audio.

In the late 1990s many computer manufacturers began to replace plug-in soundcards with a "codec" chip (actually a combined audio AD/DA-converter) integrated into the motherboard. Many of these used Intel's AC'97 specification. Others used inexpensive ACR slot accessory cards.

From around 2001 many motherboards incorporated integrated "real" (non-codec) soundcards, usually in the form of a custom chipset providing something akin to full Sound Blaster compatibility, providing relatively high-quality sound.

However, these features were dropped when AC'97 was superseded by Intel's HD Audio standard, which was released in 2004, again specified the use of a codec chip, and slowly gained acceptance. As of 2011, most motherboards have returned to using a codec chip, albeit a HD Audio compatible one, and the requirement for Sound Blaster compatibility relegated to history.

Integrated sound on other platforms

Various non-IBM PC compatible computers, such as early home computers like the Commodore 64 (1982) and Amiga (1985), NEC's PC-88 and PC-98, Fujitsu's FM-7 and FM Towns, the MSX,[11] Apple's Macintosh, and workstations from manufacturers like Sun, have had their own motherboard integrated sound devices. In some cases, most notably in those of the Amiga, C64, PC-88, PC-98, MSX, FM-7, and FM towns, they provide very advanced capabilities (as of the time of manufacture), in others they are only minimal capabilities. Some of these platforms have also had sound cards designed for their bus architectures that cannot be used in a standard PC.

Several Japanese computer platforms, including the PC-88, PC-98, MSX, and FM-7, featured built-in FM synthesis sound from Yamaha by the mid-1980s. By 1989, the FM Towns computer platform featured built-in PCM sample-based sound and supported the CD-ROM format.[11]

The custom sound chip on Amiga, named Paula, had four digital sound channels (2 for the left speaker and 2 for the right) with 8 bit resolution (although with patches, 14/15bit was accomplishable at the cost of high CPU usage) for each channel and a 6 bit volume control per channel. Sound playback on Amiga was done by reading directly from the chip-RAM without using the main CPU.

Most arcade games have integrated sound chips, the most popular being the Yamaha OPL chip for BGM coupled with a variety of DACs for sampled audio and sound effects.

Sound cards on other platforms

The earliest known soundcard used by computers was the Gooch Synthetic Woodwind, a music device for PLATO terminals, and is widely hailed as the precursor to sound cards and MIDI. It was invented in 1972.

Certain early arcade machines made use of sound cards to achieve playback of complex audio waveforms and digital music, despite being already equipped with onboard audio. An example of a sound card used in arcade machines is the Digital Compression System card, used in games from Midway. For example, Mortal Kombat II on the Midway T Unit hardware. The T-Unit hardware already has an onboard YM2151 OPL chip coupled with an OKI 6295 DAC, but said game uses an added on DCS card instead.[12] The card is also used in the arcade version of Midway and Aerosmith's Revolution X for complex looping BGM and speech playback (Revolution X used fully sampled songs from the band's album that transparently looped- an impressive feature at the time the game was released).

MSX computers, while equipped with built-in sound capabilities, also relied on sound cards to produce better quality audio. The card, known as Moonsound, uses a Yamaha OPL4 sound chip. Prior to the Moonsound, there were also soundcards called MSX Music and MSX Audio, which uses OPL2 and OPL3 chipsets, for the system.

The Apple II series of computers, which did not have sound capabilities beyond a beep until the IIGS, could use plug-in sound cards from a variety of manufacturers. The first, in 1978, was ALF's Apple Music Synthesizer, with 3 voices; two or three cards could be used to create 6 or 9 voices in stereo. Later ALF created the Apple Music II, a 9-voice model. The most widely supported card, however, was the Mockingboard. Sweet Micro Systems sold the Mockingboard in various models. Early Mockingboard models ranged from 3 voices in mono, while some later designs had 6 voices in stereo. Some software supported use of two Mockingboard cards, which allowed 12-voice music and sound. A 12-voice, single card clone of the Mockingboard called the Phasor was made by Applied Engineering. In late 2005 a company called ReactiveMicro.com produced a 6-voice clone called the Mockingboard v1 and also had plans to clone the Phasor and produce a hybrid card user-selectable between Mockingboard and Phasor modes plus support both the SC-01 or SC-02 speech synthesizers.

External sound devices

Devices such as the Covox Speech Thing could be attached to the parallel port of an IBM PC and feed 6- or 8-bit PCM sample data to produce audio. Also, many types of professional soundcards (audio interfaces) have the form of an external FireWire or USB unit, usually for convenience and improved fidelity.

Sound cards using the PCMCIA Cardbus interface were available before laptop and notebook computers routinely had onboard sound. Cardbus audio may still be used if onboard sound quality is poor. When Cardbus interfaces were superseded by Expresscard on computers since about 2005, manufacturers followed. Most of these units are designed for mobile DJs, providing separate outputs to allow both playback and monitoring from one system, however some also target mobile gamers, providing high-end sound to gaming laptops who are usually well-equipped when it comes to graphics and processing power, but tend to have audio codecs that are no better than the ones found on regular laptops.

USB sound cards

USB sound "cards", sometimes called "audio interfaces", are usually external boxes that plug into the computer via USB. A USB audio interface may describe a device allowing a computer which has a sound-card, yet lacks a standard audio socket, to be connected to an external device which requires such a socket, via its USB socket.

The USB specification defines a standard interface, the USB audio device class, allowing a single driver to work with the various USB sound devices and interfaces on the market.

Even cards meeting the older, slow, USB 1.1 specification are capable of high quality sound with a limited number of channels, or limited sampling frequency or bit depth, but USB 2.0 or later is more capable.

Uses

The main function of a sound card is to play audio, usually music, with varying formats (monophonic, stereophonic, various multiple speaker setups) and degrees of control. The source may be a CD or DVD, a file, streamed audio, or any external source connected to a sound card input.

Audio may be recorded. Sometimes sound card hardware and drivers do not support recording a source that is being played.

A card can also be used, in conjunction with software, to generate arbitrary waveforms, acting as an audio-frequency function generator. Free and commercial software is available for this purpose;[13] there are also online services that generate audio files for any desired waveforms, playable through a sound card.

A card can be used, again in conjunction with free or commercial software, to analyse input waveforms. For example, a very-low-distortion sinewave oscillator can be used as input to equipment under test; the output is sent to a sound card's line input and run through Fourier transform software to find the amplitude of each harmonic of the added distortion.[14] Alternatively, a less pure signal source may be used, with circuitry to subtract the input from the output, attenuated and phase-corrected; the result is distortion and noise only, which can be analysed.

There are programs which allow a sound card to be used as an audio-frequency oscilloscope.

For all measurement purposes a sound card must be chosen with good audio properties. It must itself contribute as little distortion and noise as possible, and attention must be paid to bandwidth and sampling. A typical integrated sound card, the Realtek ALC887, according to its data sheet has distortion of about 80 dB below the fundamental; cards are available with distortion better than -100 dB.

Sound cards with a sampling rate of 192 kHz can be used to synchronize the clock of the computer with a time signal transmitter working on frequencies below 96 kHz like DCF 77 with a special software and a coil at the entrance of the soundcard, working as antenna , .

Driver architecture

To use a sound card, the operating system (OS) typically requires a specific device driver, a low-level program that handles the data connections between the physical hardware and the operating system. Some operating systems include the drivers for many cards; for cards not so supported, drivers are supplied with the card, or available for download.

- DOS programs for the IBM PC often had to use universal middleware driver libraries (such as the HMI Sound Operating System, the Miles Audio Interface Libraries (AIL), the Miles Sound System etc.) which had drivers for most common sound cards, since DOS itself had no real concept of a sound card. Some card manufacturers provided (sometimes inefficient) middleware TSR-based drivers for their products. Often the driver is a Sound Blaster and AdLib emulator designed to allow their products to emulate a Sound Blaster and AdLib, and to allow games that could only use SoundBlaster or AdLib sound to work with the card. Finally, some programs simply had driver/middleware source code incorporated into the program itself for the sound cards that were supported.

- Microsoft Windows uses drivers generally written by the sound card manufacturers. Many device manufacturers supply the drivers on their own discs or to Microsoft for inclusion on Windows installation disc. Sometimes drivers are also supplied by the individual vendors for download and installation. Bug fixes and other improvements are likely to be available faster via downloading, since CDs cannot be updated as frequently as a web or FTP site. USB audio device class support is present from Windows 98 SE onwards.[15] Since Microsoft's Universal Audio Architecture (UAA) initiative which supports the HD Audio, FireWire and USB audio device class standards, a universal class driver by Microsoft can be used. The driver is included with Windows Vista. For Windows XP, Windows 2000 or Windows Server 2003, the driver can be obtained by contacting Microsoft support.[16] Almost all manufacturer-supplied drivers for such devices also include this class driver.

- A number of versions of UNIX make use of the portable Open Sound System (OSS). Drivers are seldom produced by the card manufacturer.

- Most present day Linux distributions make use of the Advanced Linux Sound Architecture (ALSA). Up until Linux kernel 2.4, OSS was the standard sound architecture for Linux, although ALSA can be downloaded, compiled and installed separately for kernels 2.2 or higher. But from kernel 2.5 onwards, ALSA was integrated into the kernel and the OSS native drivers were deprecated. Backwards compatibility with OSS-based software is maintained, however, by the use of the ALSA-OSS compatibility API and the OSS-emulation kernel modules.

- Mockingboard support on the Apple II is usually incorporated into the programs itself as many programs for the Apple II boot directly from disk. However a TSR is shipped on a disk that adds instructions to Apple Basic so users can create programs that use the card, provided that the TSR is loaded first.

List of sound card manufacturers

- This list is incomplete; you can help by expanding it.

- AIM

- ASUS

- Advanced Gravis Computer Technology (defunct)

- AdLib (defunct)

- Aureal Semiconductor (defunct)

- Auzentech (defunct)

- Aztech Labs

- Behavior Tech Computer

- Behringer

- C-Media

- Creative Technology

- E-mu Systems (bought out by Creative)

- Ensoniq (bought out by Creative)

- ESI

- HT Omega

- MARIAN digital audio electronics

- M-Audio

- Onkyo

- Realtek Semiconductor

- RME Audio

- Roland Corporation

- Trident Microsystems (defunct)

- Turtle Beach Systems

- VIA Technologies

- Yamaha Corporation

See also

- Loudspeaker

- Loudspeaker enclosure

- Analog Devices

- Sound chip

- EAX

- ASIO

- Audio signal processing

- Guitar effects unit

- Sound effect

- Audio Libraries (Categories)

- Codec

- DirectSound

- DirectMusic

- OpenAL

- Programmable sound generator

- Stereo

- Dolby Digital

- S Logic

- SNR

- Texture (music)

- Audio compression (data)

- PC System Design Guide

References

This article is based on material taken from the Free On-line Dictionary of Computing prior to 1 November 2008 and incorporated under the "relicensing" terms of the GFDL, version 1.3 or later.

- ↑ "Studio Recording Techniques - Recording Devices". joelezekielconfetti. Retrieved 2016-01-20.

- ↑ PC 99 System Design Guide, Intel Corporation and Microsoft Corporation, 14 July 1999. Chapter 3: PC 99 basic requirements (PC 99 System Design Guide (Self-extracting .exe archive). Requirement 3.18.3: Systems use a color-coding scheme for connectors and ports. Accessed 2012-11-26

- 1 2 3 4 http://www.joeylatimer.com/pdf/Compute!%20April%201990%20PC%20Sound%20Gets%20Serious%20by%20Joey%20Latimer.pdf

- ↑ "Winds of Progress Unleashed in "Windy City"". Computer Gaming World. July 1988. p. 8. Retrieved 3 November 2013.

- ↑ "The Gamer's Guide to Sound Boards". Computer Gaming World. September 1989. p. 18. Retrieved 4 November 2013.

- ↑ English, David (June 1992). "Sound Blaster turns Pro". Compute!. p. 82. Retrieved 11 November 2013.

- ↑ "Computing Will Never Sound the Same". Computer Gaming World (advertisement). July 1992. p. 90. Retrieved 3 July 2014.

- ↑ "Realtek". Retrieved 2013-02-27.

- ↑ Installing an LG driver on many Dells with Sigmatel 92xx chip, including the Inspiron 6400 and other models can add support for stereo mix. Reference dates from 2007 and covers Windows XP and Vista

- ↑ "Whatever happened to Wave Out Mix? - Larry Osterman's WebLog - Site Home - MSDN Blogs". Blogs.msdn.com. Retrieved 2013-02-28.

- 1 2 John Szczepaniak. "Retro Japanese Computers: Gaming's Final Frontier Retro Japanese Computers". Hardcore Gaming 101. Retrieved 2011-03-29. Reprinted from Retro Gamer (67), 2009

- ↑ System 16 - Midway T Unit Hardware

- ↑ Web page with free function generator and oscilloscope software for sound card

- ↑ Detailed discussion of distortion measurement with sound cards, including suitable cards and software

- ↑ Microsoft USB FAQ

- ↑ Universal Audio Architecture (UAA) High Definition Audio class driver version 1.0a available

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sound cards. |

- Jumper settings for many sound cards

- History of PC Sound Hardware

- Soundcards Museum

- How Stuff Works - Sound Cards

- PC Sound cards

- External Soundcard solutions

| ||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||