Juana Inés de la Cruz

| Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, O.S.H. | |

|---|---|

|

Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz by Miguel Cabrera | |

| Born |

Juana Inés de Asbaje y Ramírez de Santillana 12 November 1651 San Miguel Nepantla, New Spain, Spanish Empire |

| Died |

17 April 1695 (aged 43) Mexico City, New Spain, Spanish Empire |

| Occupation | Nun, poet, writer |

| Nationality | Mexican |

| Literary movement | Baroque |

| Relatives | Pedro Manuel de Asbaje and Isabel Ramírez (parents) |

|

| |

| Signature |

|

Sister (Spanish: Sor) Juana Inés de la Cruz, O.S.H. (English: Joan Agnes of the Cross; 12 November 1651 – 17 April 1695),was a self-taught scholar and poet of the Baroque school, and Hieronymite nun of New Spain, known in her lifetime as "The Tenth Muse." Although she lived in a colonial era when Mexico was part of the Spanish Empire, she is considered today both a Mexican writer and a contributor to the Spanish Golden Age. She stands at the beginning of the history of Mexican literature in the Spanish language. In recognition, she is honored by official government recognition and is an inspiration to artists in the modern era.

Life

She was born Juana Inés de Asbaje y Ramírez de Santillana in San Miguel Nepantla (now called Nepantla de Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz in her honor) near Mexico City. She was the illegitimate child of a Spanish Captain, Pedro Manuel de Asbaje, and a Criolla woman, Isabel Ramírez. Her father, according to all accounts, was absent from her life. She was baptized 2 December 1651 and described on the baptismal rolls as "a daughter of the Church". She was raised in Amecameca, where her maternal grandfather owned an hacienda.

Juana was a devoutly religious child who often hid in the hacienda chapel to read her grandfather's books from the adjoining library, something forbidden to girls. She learned how to read and write Latin at the age of three. By age five, she reportedly could do accounts. At age eight, she composed a poem on the Eucharist.[1]

By adolescence, Juana had mastered Greek logic, and at age thirteen she was teaching Latin to young children. She also learned the Aztec language of Nahuatl, and wrote some short poems in that language.[2]

.jpg)

In 1664, aged 12, Juana was sent to live in Mexico City. She asked her mother's permission to disguise herself as a male student so that she could enter the university there. Not being allowed to do this, she continued her studies privately. She was a lady-in-waiting at the colonial viceroy's court,[3] where she came under the tutelage of the Vicereine Leonor Carreto, wife of the Viceroy of New Spain Antonio Sebastián de Toledo. The viceroy (whom Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography names as the Marquis de Mancera), wishing to test the learning and intelligence of this 17-year-old, invited several theologians, jurists, philosophers, and poets to a meeting, during which she had to answer, unprepared, many questions, and explain several difficult points on various scientific and literary subjects. The manner in which she acquitted herself astonished all present, and greatly increased her reputation. Her literary accomplishments garnered her fame throughout New Spain. Her interest in scientific thought and experiment led to professional discussions with Isaac Newton.[3] She was much admired in the viceregal court, and declined several proposals of marriage.[1]

Life as Nun

In 1667, she entered the Monastery of St. Joseph, a community of the Discalced Carmelite nuns, as a postulant. She chose not to enter that Order, which had a strict discipline, and later, in 1669, she entered the monastery of the Hieronymite nuns, which had a more relaxed rule. She chose to become a nun so that she could study as she wished, saying she wanted "to have no fixed occupation which might curtail my freedom to study." [4]

In the convent and perhaps earlier, Sor Juana became friends with fellow savant, Don Carlos de Sigüenza y Góngora, who visited her in the convent's locutorio.[5] She stayed cloistered in the Convent of Santa Paula of the Hieronymite in Mexico City from 1669 until her death, where she collected a large library of books, studied, and wrote.[4] The Viceroy and Vicereine of New Spain became her patrons; they supported her and had her writings published in Spain.[4]

One noted critic of her writing was the bishop of Puebla, Manuel Fernández de Santa Cruz, who in November of 1690 published Sor Juana's critique of a 40-year-old sermon by Father António Vieira, a Portuguese Jesuit preacher.[6] In addition to publishing this without her permission (albeit under a pseudonym), he told her to focus on religious instead of secular studies.[7]

In response to critics of her writing, Juana wrote a letter, Respuesta a Sor Filotea (Reply to Sister Philotea), in which she defended women's right to education saying, "Oh, how much harm would be avoided in our country" if women were able to teach women in order to avoid the danger of male teachers in intimate setting with young female students. Sister Juana said that such hazards "would be eliminated if there were older women of learning, as Saint Paul desires, and instructions were passed down from one group to another, as in the case with needlework and other traditional activities."[8] In response, Francisco de Aguiar y Seijas, Archbishop of Mexico joined other high-ranking officials in condemning Sor Juana's "waywardness". By 1693, Sor Juana seemingly ceased writing rather than risk official censure. However, there is no undisputed evidence of her renouncing devotion to letters, though there are documents showing her agreeing to undergo penance. Her name is affixed to such a document in 1694, but given her deep natural lyricism, the tone of these supposed hand-written penitentials is in rhetorical and autocratic Church formulae; one is signed "Yo, la peor de todas" ("I, the worst of all women") She is said to have sold all her books,[1] then an extensive library of over 4,000 volumes, and her musical and scientific instruments as well. Other sources report that her defiance toward the church led to all of her books and instruments being confiscated.[3] Only a few of her writings have survived, which are known as the Complete Works. According to Octavio Paz, her writings were saved by the vicereine.[9]

She died after ministering to other nuns stricken during a plague, on 17 April 1695. Sigüenza y Góngora delivered the eulogy at her funeral.[10]

Works

The Dream

The Dream, a long philosophical and descriptive silva (a poetic form combining verses of 7 and 11 syllables), “deals with the shadow of night beneath which a person [11] falls asleep in the midst of quietness and silence, where night and day animals participate, either dozing or sleeping, all urged to silence and rest by Harpocrates. The person's body ceases its ordinary operations,[12] which are described in physiological and symbolical terms, ending with the activity of the imagination as an image-reflecting apparatus: the Pharos. From this moment, her soul, in a dream, sees itself free at the summit of her own intellect; in other words, at the apex of an own pyramid-like mount, which aims at God and is luminous.[13]

There, perched like an eagle, she contemplates the whole creation,[14] but fails to comprehend such a sight in a single concept. Dazzled, the soul's intellect faces its own shipwreck, caused mainly by trying to understand the overwhelming abundance of the universe, until reason undertakes that enterprise, beginning with each individual creation, and processing them one by one, helped by the Aristotelic method of ten categories.[15]

The soul cannot get beyond questioning herself about the traits and causes of a fountain and a flower, intimating perhaps that his method constitutes a useless effort, since it must take into account all the details, accidents, and mysteries of each being. By that time, the body has consumed all its nourishment, and it starts to move and wake up, soul and body are reunited. The poem ends with the Sun overcoming Night in a straightforward battle between luminous and dark armies, and with the poet's awakening.”[15]

Other notable works

- Loa to Divine Narcissus, (Spanish "El divino Narciso") (see Jauregui 2003, 2009)

Studies of Juana Inés de la Cruz

There is a vast scholarly literature on Sor Juana in Spanish, English, French, and German.

Her works have appeared in translation. An early translation of Sor Juana's work into English was Ten Sonnets from Sor Juana Inez de la Cruz [sic], 1651-1695: Mexico's Tenth Muse, published in Taxco, Guerrero, in 1943. The translator was Elizabeth Prall Anderson who settled in Taxco. One musical work attributed to Sor Juana survives from the archive at Guatemala Cathedral. This is a 4 part villancico, Madre, la de los primores.

An important translation to English of a work by Juana Inés de la Cruz for a wide readership is published as Poems, Protest, and a Dream in a Penguin Classics paperback in March 1, 1997, which includes her response to authorities censuring her.

Arguably the most important book devoted to Sor Juana, written by Nobel Prize laureate Octavio Paz in Spanish and translated to English in 1989 as Sor Juana: Or, the Traps of Faith (translated by Margaret Sayers Peden). This work examines and contemplates Sor Juana's poetry and life in the context of the history of New Spain, particularly focusing on the difficulties women then faced while trying to thrive in academic and artistic fields. Paz describes how he had been drawn to her work by the enigmas of Sor Juana's personality and life paths. "Why did she become a nun? How could she renounce her lifelong passion for writing and learning?"[16]

In his book, Paz makes a thorough analysis of Sor Juana's poetry and traces some of her influences to the Spanish writers of the Golden Age and the Hermetic tradition, mainly derived from the works of a noted Jesuit scholar of her era, Athanasius Kircher. Paz analyses Sor Juana's most ambitious and extensive poem, "First Dream" ("Primero Sueño") as largely a representation of the desire of knowledge through a number of hermetic symbols, albeit transformed in her own language and skilled image-making abilities. In conclusion, Paz makes the case that Sor Juana's works were the most important body of poetic work produced in the Americas until the arrival of 19th-century figures such as Emily Dickinson and Walt Whitman.

Tarsicio Herrera Zapién, a classical scholar, has devoted much of his career to the study of Sor Juana's works. Some of his publications (in Spanish) include Buena fe y humanismo en Sor Juana: diálogos y ensayos: las obras latinas: los sorjuanistas recientes (1984); López Velarde y sor Juana, feministas opuestos: y cuatro ensayos sobre Horacio y Virgilio en México (1984); Poemas mexicanos universales: de Sor Juana a López Velarde (1989) and Tres siglos y cien vidas de Sor Juana (1995).

Historical memory and influence

Sor Juana was a famous and controversial figure in the seventeenth century. In the modern era, she has been honored in Mexico as well as being the part of a political controversy in the late twentieth century. During renovations at the cloister in the 1970s, bones were found that are believed to be those of Sor Juana. Also found at the same time was a medallion similar to the one depicted in portraits of Sor Juana. The medallion was kept by Margarita López Portillo, the sister of President José López Portillo (1976-1982). During the tercentennial of Sor Juana's death in 1995, a member of the Mexican congress called on Margarita López Portillo to return the medallion, which she said taken for "safekeeping." She returned it to Congress on November 14, 1995, with the event and description of the controversy reported in the New York Times a month later. Whether or not the medallion is Sor Juana's, the incident sparked discussions about Sor Juana and abuse of official power in Mexico.[17]

Official recognition by the Mexican government

She was honored by the Mexican government in significant ways.

- Sor Juana's name was inscribed in gold on the wall of honor in the Mexican congress in April 1995.[18]

- Sor Juana is pictured on the obverse of the 200 pesos bill issued by the Banco de Mexico.[19]

- Sor Juana also appears on the 1000 pesos coin minted by Mexico between 1988 and 1992

- The convent in Mexico City in which she lived the last 27 years of her life and where she wrote most of her work is today the University of the Cloister of Sor Juana in the historic center of Mexico City.

Inspiration and influence

Sor Juana has been the inspiration for film makers and authors of poetry, plays, opera, and literary fiction.

- María Luisa Bemberg wrote and directed the 1990 film, Yo, la peor de todas (I, the Worst of All), about the life of Sor Juana

- A telenovela about her life, Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz (telenovela) was created in 1962.

- Diane Ackerman wrote a dramatic verse play, Reverse Thunder, about Sor Juana (1992)

- Alicia Gaspar de Alba's historical novel, Sor Juana's Second Dream (1999)

- Jesusa Rodríguez has produced a number of works concerning Sor Juana, including Sor Juana en Almoloya and Striptease de Sor Juana, based on Juana's poem, "Primero Sueño"

- Canadian novelist Paul Anderson devoted 12 years writing a 1300 page novel entitled Hunger's Brides (pub. 2004) on Sor Juana. His novel won the 2005 Alberta Book Award.

- Helen Edmundson's play The Heresy of Love, based on the life of Sor Juana, was premiered by the Royal Shakespeare Company in early 2012 and revived by Shakespeare's Globe in 2015.[20]

- Composer Daniel Crozier and librettist Peter M. Krask wrote With Blood, With Ink, an opera based around her life, while both were students at Baltimore's Peabody Institute in 1993. The work was premiered at Peabody and won first prize in the National Operatic and Dramatic Association's Chamber Opera Competition. In May 2000, excerpts from the opera were included in the New York City Opera's Showcasing American Composers Series. The work in its entirety was premiered by the Fort Worth Opera on April 20, 2014 and recorded by Albany Records.

See also

References

- 1 2 3

Wilson, James Grant; Fiske, John, eds. (1900). "Cruz, Juana Inés de la". Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. New York: D. Appleton.

Wilson, James Grant; Fiske, John, eds. (1900). "Cruz, Juana Inés de la". Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. New York: D. Appleton. - ↑ Profile at Poets.org

- 1 2 3 Murray, Stuart (2009). The Library: An Illustrated History. Chicago: Skyhorse Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8389-0991-1.

- 1 2 3 http://www.biography.com/people/sor-juana-in%C3%A9s-de-la-cruz-38178#synopsis

- ↑ Irving A. Leonard, Baroque Times in Old Mexico, Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, pp. 191-192.

- ↑ http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/1072584/Manuel-Fernandez-de-Santa-Cruz

- ↑ http://www.biography.com/people/sor-juana-in%C3%A9s-de-la-cruz-38178#writing-development

- ↑ Murray, Stuart A.P. (2009). The library : an illustrated history. New York, NY: Skyhorse Pub. ISBN 9781602397064.

- ↑ Paz, Octavio (1988). Sor Juana or the Traps of Faith. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University.

- ↑ Leonard 1959, ibid. 191-92.

- ↑ In the final verse we come to know it is Sor Juana herself because she uses the first person, feminine.

- ↑ Sor Juana is inspired by Fray Luis de Granada's Introducción al Símbolo de la Fe, where an extended verbal description of physiological functions is the closest match to what is found in the poem.

- ↑ It must be understood that this light of intellect is Grace given by God.

- ↑ This pinnacle of contemplation is clearly preceded by Saint Augustine (Confessions, X, VIII, 12), who also inspired Petrarch's letter about the contemplation of the world created by God from the summit of a mountain (in his letter Familiares, IV, 1)

- 1 2 Olivares Zorrilla, Rocío. “The Eye of Imagination. Emblems in the Baroque Poem The Dream, by Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz”, Emblematica. An Interdisciplinary Journal for Emblem Studies, volume 18 (2010): 111-61: 115-17.

- ↑ Paz p. 2

- ↑ Anthony DePalma, "The Poet's Medallion: A Case of Finders Keepers?" New York Times, Friday, December 15, 1995.

- ↑ Anthony DePalma, "The Poet's Medallion", New York Times, Friday, December 15, 1995.

- ↑ "Billete de 200 pesos". Bank of Mexico. Retrieved 2011-07-26.

- ↑ Spencer, C. The Heresy of Love, RSC, Stratford-upon-Avon, review. The Telegraph. Retrieved March 19, 2013

Sources

- The Juana Inés de la Cruz Project Dartmouth College. Retrieved: 2010-05-09.

- Sor Juana Ines de la Cruz (1648-1695) Oregon State University. Retrieved: 2010-05-09.

- Universidad del Claustro de Sor Juana. Retrieved: 2010-08-03.

Further reading

- ALATORRE, Antonio, Sor Juana a través de los siglos. México: El Colegio de México, 2007.

- BENASSY-BERLING, Marié-Cécile, Humanisme et Religion chez Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz: la femme et la cultura au 17e siècle. Paris: Editions Hispaniques, 1982. ISBN 2-85355-000-1

- BEAUCHOT, Mauricio, Sor Juana, una filosofía barroca, Toluca: UAM, 2001.

- BUXÓ, José Pascual, Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz: Lectura barroca de la poesía, México, Renacimiento, 2006.

- CORTES, Adriana, Cósmica y cosmética, pliegues de la alegoría en sor Juana Inés de la Cruz y Pedro Calderón de la Barca. Madrid: Vervuert, 2013. ISBN 978-84-8489-698-2

- GAOS, José. “El sueño de un sueño”. Historia Mexicana, 10, 1960.

- JAUREGUI, Carlos A. “Cannibalism, the Eucharist, and Criollo Subjects.” In Creole Subjects in the Colonial Americas: Empires, Texts, Identities. Ralph Bauer & Jose A. Mazzotti (eds.). Chapel Hill: Omohundro Institute of Early American History & Culture, Williamsburg, VA, U. of North Carolina Press, 2009. 61-100.

- JAUREGUI, Carlos A. “El plato más sabroso’: eucaristía, plagio diabólico, y la traducción criolla del caníbal.” Colonial Latin American Review 12:2 (2003): 199-231.

- MERKL, Heinrich, Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz. Ein Bericht zur Forschung 1951-1981. Heidelberg: Winter, 1986. ISBN 3-533-03789-4

- MURATTA BUNSEN, Eduardo, "La estancia escéptica de Sor Juana". Sor Juana Polímata. Ed. Pamela H. Long. México: Destiempos, 2013. ISBN 978-607-9130-27-5

- NEUMEISTER, Sebastian, "Disimulación y rebelión: El Político silencio de Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz". La cultura del barroco español e iberoamericano y su contexto europeo. Ed. Kazimierz Sabik and Karolina Kumor, Varsovia: Insituto de Estudios Ibéricos e Iberoamericanos de la Universidad de Varsovia, 2010. ISBN 978-83-60875-84-1

- OLIVARES ZORRILLA, Rocío, "The Eye of Imagination: Emblems in the Baroque Poem 'The Dream,' by Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz", in Emblematica. An Interdisciplinary Journal for Emblem Studies, AMC Press, Inc., New York, vol. 18, 2010: 111-161.

- ----, La figura del mundo en "El sueño", de Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz. Ojo y "spiritus phantasticus" en un sueño barroco, Madrid, Editorial Académica Española, 2012. ISBN 978-3-8484-5766-3

- PERELMUTER, Rosa, Los límites de la femineidad en sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, Madrid, Iberoamericana, 2004.

- PAZ, Octavio. Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz o las trampas de la fe. México: Fondo de Cultura Económica, 1982.

- PFLAND, Ludwig, Die zehnte Muse von Mexiko Juana Inés de la Cruz. Ihr Leben, ihre Dichtung, ihre Psyche. München: Rinn, 1946.

- RODRÍGUEZ GARRIDO, José Antonio, La Carta Atenagórica de Sor Juana: Textos inéditos de una polémica, México: UNAM, 2004. ISBN 9703214150

- ROSAS LOPATEGUI, Patricia, Oyeme con los ojos : de Sor Juana al siglo XXI; 21 escritoras mexicanas revolucionarias. México: Universidad Autónoma Nuevo León, 2010. ISBN 978-607-433-474-6

- SABAT DE RIVERS, Georgina, El «Sueño» de Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz: tradiciones literarias y originalidad, Londres: Támesis, 1977.

- SORIANO, Alejandro, La hora más bella de Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, México, CONACULTA, Instituto Queretano de la Cultura y las Artes, 2010.

- WEBER, Hermann, Yo, la peor de todas – Ich, die Schlechteste von allen. Karlsruhe: Info Verlag, 2009. ISBN 978-3-88190-542-8

External links

- Works by Juana Inés de la Cruz at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Sor Juana, the Poet: The Sonnets from National Endowment for the Humanities

- Sor Juana, la poetisa: Los sonetos from National Endowment for the Humanities

- The Imperfect Sex: Why Is Sor Juana Not a Saint? by Jorge Majfud

- The Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz Project

- Academic resource on the poetry of Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz

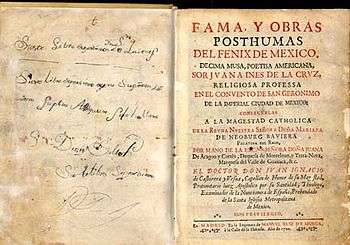

- On-line facsimile edition of Sor Juana's Fama y obras posthumas

- Six sonnets in Spanish with English translations

- Free scores by Juana Inés de la Cruz in the Choral Public Domain Library (ChoralWiki)

|

.jpg)