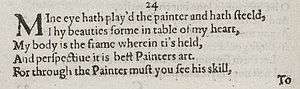

Sonnet 24

Mine eye hath play'd the painter and hath steel'd,

Thy beauty's form in table of my heart;

My body is the frame wherein 'tis held,

And perspective it is best painter's art.

For through the painter must you see his skill,

To find where your true image pictur'd lies,

Which in my bosom's shop is hanging still,

That hath his windows glazed with thine eyes.

Now see what good turns eyes for eyes have done:

Mine eyes have drawn thy shape, and thine for me

Are windows to my breast, where-through the sun

Delights to peep, to gaze therein on thee;

Yet eyes this cunning want to grace their art,

They draw but what they see, know not the heart.

Sonnet 24 is one of 154 sonnets written by the English playwright and poet William Shakespeare, and is a part of the Fair Youth sequence.

In the sonnet, Shakespeare treats the commonplace Renaissance conceit connecting heart and eye. Although it relates to other sonnets that explore this theme, Sonnet 24 is considered largely imitative and conventional.

Structure

Sonnet 24 is an English or Shakespearean sonnet. English sonnets contain fourteen lines, including three quatrains and a final couplet. It follows the typical rhyme scheme of the form: abab cdcd efef gg. This sonnet, like many in the sequence, is written in iambic pentameter, a type of poetic metre which has five pairs of unstressed/stressed syllables per line.

| Stress | x | / | x | / | x | / | x | / | x | / |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Syllable | Mine | eyes | have | drawn | thy | shape, | and | thine | for | me |

Source and analysis

Edward Capell amended quarto "steeld" to "stelled," a word more closely related to the metaphor of the first quatrain. Edward Dowden notes parallels for the opening conceit in Henry Constable's Diana and in Thomas Watson's Tears of Fancy.

The poem's central conceit, the dialogue between heart and eye, was a period cliché. Sidney Lee traces it to Petrarch and notes analogues in the work of Ronsard, Michael Drayton, and Barnabe Barnes.

The poem has not enjoyed a high reputation. Henry Charles Beeching speculates that it might be a half-serious spoof of a cliched type of poem. George Wyndham is among the few to take it completely seriously, providing a neoplatonic reading.

"Perspective" is the key trope in the second half of the poem, as it introduces the idea of the connection between speaker and beloved. Some editors have assumed that "perspective" was used, as often in the Renaissance, to refer to a specific type of optical illusion sometimes called a perspective house;[1] however, Thomas Tyler and others demonstrated that the word was also known in its modern sense during the time.

Sonnet 46 and Sonnet 47 also present the eyes of the speaker as a character in the poem. Note that in Sonnet 24 both the singular eye and the plural eyes are used for the eyes of the speaker, contrary to Sonnet 46 and Sonnet 47 where only the singular is used.

References

- ↑ Larsen, Kenneth J. "Sonnet 24". Essays on Shakespeare's Sonnets. Retrieved 23 December 2014.

Further References

- Alden, Raymond (1916). The Sonnets of Shakespeare, with Variorum Reading and Commentary. Houghton-Mifflin, Boston.

- Baldwin, T. W. (1950). On the Literary Genetics of Shakspeare's Sonnets. University of Illinois Press, Urbana.

- Booth, Stephen (1977). Shakespeare's Sonnets. Yale University Press, New Haven.

- Dowden, Edward (1881). Shakespeare's Sonnets. London.

- Evans, G. Blakemore, Anthony Hecht, (1996). Shakespeare's Sonnets. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- Hubler, Edwin (1952). The Sense of Shakespeare's Sonnets. Princeton University Press, Princeton.

- Schoenfeldt, Michael (2007). The Sonnets: The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare’s Poetry. Patrick Cheney, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- Tyler, Thomas (1989). Shakespeare’s Sonnets. London D. Nutt.

- Vendler, Helen (1997). The Art of Shakespeare's Sonnets. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

External links

-

Works related to Sonnet 24 (Shakespeare) at Wikisource

Works related to Sonnet 24 (Shakespeare) at Wikisource - Paraphrase and analysis (Shakespeare-online)

- Analysis

| ||||||||||

.png)