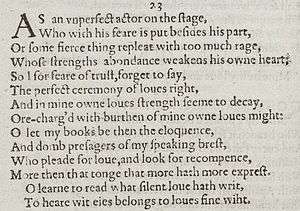

Sonnet 23

As an unperfect actor on the stage,

Who with his fear is put beside his part,

Or some fierce thing replete with too much rage,

Whose strength's abundance weakens his own heart;

So I, for fear of trust, forget to say

The perfect ceremony of love's rite,

And in mine own love's strength seem to decay,

O'ercharg'd with burthen of mine own love's might.

O! let my books be then the eloquence

And dumb presagers of my speaking breast,

Who plead for love, and look for recompense,

More than that tongue that more hath more express'd.

O! learn to read what silent love hath writ:

To hear with eyes belongs to love's fine wit.

Sonnet 23 is one of 154 sonnets written by the English playwright and poet William Shakespeare, and is a part of the Fair Youth sequence.

In the sonnet, the speaker compares himself to an actor on stage who has frozen up and cannot speak, but he hopes that his love will understand him through this poem. It is of special interest because of its use of a metaphor drawn from acting, a figure that has led to much attention for what the poem might reveal about Shakespeare's attitude towards sonnet writing, love poetry, and his professions as a playwright and a poet.

Paraphrase

The actor doesn’t know his lines and due to his fear and nervousness, he loses his mastery of his role, also known as his “part.” The actor is so passionate about his job that his passion is likened to a “fierce thing,” an inhuman beast that has so much fervor and energy that it collapses within itself. This lion-like heart gives out on stage. This paralyzing fear has stripped the actor of his self-trust, the lifeblood of an actor. He is petrified of the responsibility that has been thrust upon him. Because of this, he forgets to say the right words in a certain love ritual. And this reminds him of how his own love’s fortitude is withering due to the burden of his own love’s strength. Ironically, the object of his love is acting. So he loves acting too much to effectively act. The sonnet then turns into a plea, a plea that his plays can be the silent indicators of his heart, a representation of his feelings in paper form. He needs his plays to do this because he can not accurately articulate his feelings. His plays plead for the affection that his heart seeks; they seek a return on what his heart is giving: which is endless affection for the object of the play. Since he is unable to iterate his words, the plays cry out for love even more than his words; the poet eagerly awaits the full love that might await a ready speaker who successfully speaks romantically. The poet pleads with the object of the poem to understand his silent plays that beg for love; for the object to use their eyes as if they were ears listening to romantic words.

Context

Sonnet 23 is part of what are known as the "Fair Youth" sonnet sequence, poems 1-126. It was first published, along with the other "Fair Youth" and "Dark Lady" sonnets, by Thomas Thorpe in the 1609 Quarto. The date that Shakespeare wrote this sonnet is debated, however. If Thorpe numbered the sonnets in the order in which they were written, then Sonnet 23 was written before 1596. This is because, according to GB Harrison, Sonnet 107—using its references to Queen Elizabeth—can be dated to the year 1596.[1]

Other scholars disagree with dating the sonnets by the order they appeared in the Quarto. One scholar, Brents Stirling, in his revised ordering of the sonnets, argues that Sonnet 23 takes place in a "later phase" in the "poet-friendship relationship". In the timeline that Stirling describes, Sonnet 23 "celebrates renewal and rededication" of the relationship. In relation to Sonnet 107, Sonnet 23 is placed within the same "group" that Stirling creates.[2]

As for the subject of Sonnet 23, most scholars have narrowed the identity of the "Fair Youth" down to two contenders: William Herbert, Earl of Pembroke, and Henry Wriothesley, Earl of Southampton.[3] One scholar, Katherine Duncan-Jones, argues that William Herbert is both the "Mr. W.H." of the dedication and the subject of sonnets 1-126. She cites Shakespeare's financial incentive for dedicating the Quarto to Herbert; the Earl's "reluctance to marry" and references to Sonnet 116 in his own writing are a few of her reasons for believing that he is also the fair youth.[4] Scholar Kenneth Larsen also argues for Herbert, on the grounds of parallels between Sonnet 125 and events at the coronation of James I.[5] Despite this, it has been noted that in the early 1590s, Wriothesley refused to marry as well,[6] and Duncan-Jones acknowledges that sonnets written around the time of 1592-95 may have been originally addressed to Henry Wriothesley.[4]

It's also important to note that Shakespeare was the only prominent writer publishing both plays and poetry at this time, since Sonnet 23 directly involves allusions to performance and theatre. Although the sonnet tells the subject to read his poems and understand his love rather than rely on a performance, this directly contradicts Shakespeare's writing style within his plays, where he "presents the writing of love poetry in general, and sonnets in-particular, as ridiculous".[4] Patrick Cheney also notes that Shakespeare’s plays tends to emphasize “the superior effectiveness of performing an emotion rather than speaking about it." Within Sonnet 23, this is further complicated by the comparisons Shakespeare makes, first comparing himself to an actor and then his collection of poems to a play.[7]

Structure

Sonnet 23 is a standard Shakespearean Sonnet. There are 14 lines of iambic pentameter. Like other sonnets, the rhyme scheme is ABABCDCDEFEFGG. The form consists of three quatrains and a couplet. After the octave (the first two quatrains) there is usually a significant thematic twist referred to as the volta. This volta is evident in Sonnet 23, as the first eight lines of the poem describe what has happened to the speaker-poet. Scholar Helen Vendler says, “the octave seems to imply that the cause of the tongue-tiedness lies in the psychology of the speaker-poet.” This analysis points to a shift in the tone of the poem, in other words, a volta. The overall framing of the sonnet shines a light on the volta as well. The “A” lines in the octave are parallel thematically, as are B,C, and D. According to Vendler, “Careful parallels are drawn between A and A’ by fear and perfect (unperfect), between B and B’ by strength and own (his/mine).” She says when Shakespeare frames a sonnet this intentionally, “something is about to burst loose.”[8] That something is the volta.

In line one, the speaker is an unperfect actor. In like six, there is a perfect ceremony of love’s right. Another theme is loving something so much you come to fear it. There are references to fear or love in lines 2, 5, 6, 7, 8, 11, 13, and 14. It is very prevalent. Strength and might, or the lack thereof, are also addressed frequently, such as in lines 4, 7, and 8. Sight and sound conflict throughout the whole piece as well, as sight is referenced to in line 1 “stage,” line 9 “books,” line 13 “read,” line 13 “silent,” and line 14 “eyes.” Sound is referred to in lines 1 “stage,” line 10 “dumb” “speaking,” line 11 “plead,” line 12 “tongue” “expressed,” and line 14 “hear.” It all converges on line 14, the ending of the poem. There’s only one period in this version of the sonnet, after the last word. In Duncan-Jones version of this poem, in line 6 the word “right” is used. “The perfect ceremony of love’s right.” In many other versions, the line ends with the word “rite,” like a marriage rite. In the footnotes in Duncan-Jones’ version of Sonnet 23, she suggests a double meaning of the word right/rite, like the word is interchangeable.[4]

| Stress | x | / | x | / | x | / | x | / | x | / |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Syllable | So | I | for | fear | of | trust | for | get | to | say |

Source and analysis

Hermann Isaac notes parallels to the central dilemma of the poem ranging from Petrarch, the Renaissance locus for love-conceits, through Wyatt and Edmund Spenser, to Walter Raleigh and Samuel Daniel. The reference to acting has struck some critics as relevant to the author's biography. George Steevens, an advocate of early composition, argued that Shakespeare might have derived the image from watching performances of traveling troupes in Stratford; Malone suggested that the image implies familiarity with acting, not spectating. However, the image is not unique to Shakespeare and need not be taken as personal.

"For fear of trust" has drawn different, though not necessarily contradictory, glosses. Nicolaus Delius has it "from want of self-confidence," with which Edward Dowden substantially agrees; Thomas Tyler adds "for fear that I shall not be trusted," and Beeching agrees that "the trust is active."

"Dumb presagers" is sometimes seen as a continuation of the acting metaphor; a dumb show often preceded each act of Elizabethan plays. Fleay suggests a more specific indebtedness to Daniel's Complaint of Rosamond, 19.

The principal interpretive issue relates to "books" in line 9. George Sewell and Edward Capell, among others, supported emendation to "looks," principally because the syntactical connection with "presagers" seems to require a word in line 9 that can evoke future time. Both words fit into the trope of the lover struck dumb by his love, and hoping to use his books (or looks) to make himself understood. Editors from Malone to Booth and William Kerrigan have defended the quarto reading, and most modern editors generally retain "books."

Exegesis

According to Joel Fineman, Shakespeare’s sonnets portray language as “corruptingly linguistic rather than something ideally specular.” He cites 23’s conclusion — “To hear with eyes belongs to love’s fine wit” — to illuminate Shakespeare’s fixation on the shortcomings of words, stating that many sonnets “speak against a strong tradition, not only poetic, of linguistic idealization for which words in some sense are the things of which they speak.” [9]

Vendler expands on this idea, writing that “in a passage such as [23,] the (inevitable) distance between composing author and fictive speaker narrows to the vanishing point.” She says that the sonnet gets at the “stranglehold” of both the poem and Shakespeare’s prolific literary mind—both the author and the “character” of 23 desire to express too many things at once. Vendler states that language is not the only barrier to expression in 23 though, continuing to say that when the poem recognizes “that tongue” in line 12 as a rival to the “character,” Shakespeare intends “the tongue-tiedness rather as a fear of trusting the audience--the potentially faithless beloved.” [10]

Manfred Pfister writes that 23 is an example of Shakespeare combining poetry and playwriting in the sonnets. Similar to notions of “character” in the work of Fineman and Vendler, Pfister argues that each sonnet has a “speaker” that, much like a character in a play, delivers the sonnet with an awareness of the present moment, what has happened in the immediate past, and the audience hearing the text.[11]

In opposition to characterizing the sonnet “speaker,” University of Wisconsin-Madison English professor Heather Dubrow writes that the sonnets are “plotted” too often. She argues that narrativizing them and applying a biographical lens to them is unwise because of how little we know about their original form.[12]

Regardless of authorship, Patrick Cheney writes that the poem’s focus on both the theater and “books” is useful. “The complication helps make its own point: Shakespeare’s ingrained thinking process both separates and intertwines the two modes of his professional career...Perhaps we can see Shakespeare presenting Will as a (clowning) man of the theatre who nonetheless has managed to write poetry of educational value -- and is saying so in a Petrarchan sonnet.” Cheney goes on to say that Sonnet 23’s purpose is to make a statement about the uses of theater and poetry. 23 illuminates live performance’s inability to capture the “integrity” of timid infatuation.[13]

Interpretations

- John Gielgud, for the 2002 compilation album, When Love Speaks (EMI Classics)

References

Footnotes

- ↑ Fort, J.A. (1933). "THE ORDER AND CHRONOLOGY OF SHAKESPEARE'S SONNETS". Review of English Studies (33): 19–23.

- ↑ Stirling, Brents (1968). The Shakespeare Sonnet Order: Poems and Groups. University of California Press. pp. 41–44.

- ↑ Delahoyde, Michael. "SHAKE-SPEARE'S SONNETS". Washington State University.

- 1 2 3 4 Skakespeare, William (August 21, 1997). Duncan-Jones, Katherine, ed. Shakespeare's Sonnets. Arden Shakespeare; 3rd edition. ISBN 1903436575.

- ↑ Larsen, Kenneth J. "Mr. W.H.". Essays on Shakespeare's Sonnets. Retrieved 14 December 2014.

- ↑ Delahoyde, Michael. "SHAKE-SPEARE'S SONNETS". Washington State University. Retrieved 5 October 2014.

- ↑ Cheney, Patrick (Nov 25, 2004). Shakespeare, National Poet-Playwright. Cambridge University Press. p. 221.

- ↑ Vendler, Helen (1997). The Art of Shakespeare's Sonnets, Volume 1. Harvard University Press. p. 138.

- ↑ Fineman, Joel (1986). Shakespeare's perjured eye: the invention of poetic subjectivity in the sonnets. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 116–118.

- ↑ Vendler, Helen (1997). The Art of Shakespeare's Sonnets, Volume 1. Harvard University Press. pp. 138–140.

- ↑ Pfister, Manfred (Jan 1, 2005). Müller-Zettelmann, Eva, ed. Theory Into Poetry: New Approaches to the Lyric. Rodopi. p. 210.

- ↑ Dubrow, Heather (1996). "Incertainties now crown themselves assur'd: The Politics of Plotting Shakespeare's Sonnets". Shakespeare Quarterly 47 (3): 291. doi:10.2307/2871379.

- ↑ Cheney, Patrick (Nov 25, 2004). Shakespeare, National Poet-Playwright. Cambridge University Press. pp. 220–225.

Sources

- Alden, Raymond (1916). The Sonnets of Shakespeare, with Variorum Reading and Commentary. Houghton-Mifflin, Boston.

- Baldwin, T. W. (1950). On the Literary Genetics of Shakspeare's Sonnets. University of Illinois Press, Urbana.

- Booth, Stephen (1977). Shakespeare's Sonnets. Yale University Press, New Haven.

- Dowden, Edward (1881). Shakespeare's Sonnets. London.

- Evans, G. Blakemore, Anthony Hecht, (1996). Shakespeare's Sonnets. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- Hubler, Edwin (1952). The Sense of Shakespeare's Sonnets. Princeton University Press, Princeton.

- Schoenfeldt, Michael (2007). The Sonnets: The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare’s Poetry. Patrick Cheney, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- Tyler, Thomas (1989). Shakespeare’s Sonnets. London D. Nutt.

- Vendler, Helen (1997). The Art of Shakespeare's Sonnets. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

External links

Works related to Sonnet 23 (Shakespeare) at Wikisource

Works related to Sonnet 23 (Shakespeare) at Wikisource- Paraphrase and analysis (Shakespeare-online)

- Facsimile of Sonnet 23 from 1609 Quarto

- Analysis

| ||||||||||

.png)