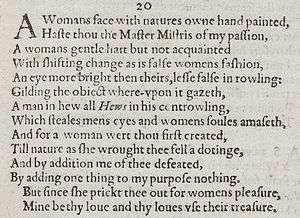

Sonnet 20

A woman's face with nature's own hand painted,

Hast thou, the master mistress of my passion;

A woman's gentle heart, but not acquainted

With shifting change, as is false women's fashion:

An eye more bright than theirs, less false in rolling,

Gilding the object whereupon it gazeth;

A man in hue, all 'hues' in his controlling,

Which steals men's eyes and women's souls amazeth.

And for a woman wert thou first created;

Till Nature, as she wrought thee, fell a-doting,

And by addition me of thee defeated,

By adding one thing to my purpose nothing.

But since she prick'd thee out for women's pleasure,

Mine be thy love and thy love's use their treasure.

Sonnet 20 is one of the best-known of 154 sonnets written by the English playwright and poet William Shakespeare. Part of the Fair Youth sequence (which comprises sonnets 1-126), the subject of the sonnet is widely interpreted as being male, thereby raising questions about the sexuality of its author. In this sonnet (as in, for example, Sonnet 53) the beloved's beauty is compared to both a man's and a woman's.

Structure

Sonnet 20 is a typical English of Shakespearean sonnet, containing three quatrains and a couplet for a total of fourteen lines. It follows the rhyme scheme of this type of sonnet, abab cdcd efef gg. Sonnet 20 departs from the sequence's typical use of iambic pentameter, a type of poetic metre that consists of five pairs of unstressed/stressed syllables per line. Each of the lines in this sonnet contains an extra eleventh syllable.

Context

Sonnet 20 is most often considered to be a member of the “Fair Youth” group of sonnets, in which most scholars agree that the poet addresses a young man. This interpretation contributes to common assumption of the homosexuality of Shakespeare, or at least the speaker of his sonnet. The position of Sonnet 20 also influences its analysis and examinations. William Nelles, of the University of Massachusetts, Dartmouth, claims that, “Sonnet 20 splits readers into two groups: those who see an end to any clear sequence after this point, and those who read on, finding a narrative line connecting the rest of the sonnets in a meaningful pattern.”[1] Scholars have suggested countless motivations or means of organizing Shakespeare’s sonnets in a specific sequence or system of grouping. Some see the division between the sonnets written to the “young man,” while others do not. A number of academics believe the sonnets may be woven into some form of complex narrative, while “Paul Edmondson and Stanley Wells confidently assert that the sonnets are ‘better thought of as a collection than a sequence, since…the individual poems do not hang together from beginning to end as a single unity…Though some of the first 126 poems in the collection unquestionably relate to a young man, others could relate to either a male or female.’”[1]

Sexuality

The modern reader may read sonnet 20 and question whether or not Shakespeare’s sexuality is reflected in this sonnet. When looking at the sexual connotations in this sonnet it is important to reflect on what homoerotism meant during the time that Shakespeare was writing. Casey Charles discusses the idea that there was no official identity for a gay person at this time. There were words that identified what we would consider to be homosexual behaviour, but the idea of a “gay culture” or "gay identity" did not exist.[2] Charles goes on to say that early modern laws against sodomy had very few transgressors, which means that either people did not commit these crimes of homosexuality or these acts were more socially acceptable than the modern reader would think. Shakespeare’s awareness of the possible homoeroticism in Sonnet 20 does not necessarily illuminate whether or not he himself was actually practicing homosexual behavior.[3]

One of the most famous accounts to raise the issue of homoeroticism in this sonnet is Oscar Wilde's short story "The Portrait of Mr. W.H.", in which Wilde, or rather the story's narrator, describes the puns on "will" and "hues" throughout the sonnets, and particularly in the line in sonnet 20, "A man in hue all hues in his controlling," as referring to a seductive young actor named Willie Hughes who played female roles in Shakespeare's plays. However, there is no evidence for the existence of any such person. (A "hue" was a servant; see OED, "hewe". The original word in the Quarto for "hues" is "Hews.")

Analysis

While there is much evidence that suggests the narrator’s homosexuality, there are also countless academics who have argued against the theory. Both approaches can be used to analyze the sonnet.

Philip C. Kolin of the University of Southern Mississippi interprets several lines from the first two quatrains of Sonnet 20 as written by a homosexual figure. One of the most common interpretations of line 2 is that the speaker believes, “the young man has the beauty of a woman and the form of a man...Shakespeare bestows upon the young man feminine virtues divorced from all their reputedly shrewish infidelity.”[4] In other words, the young man possesses all the positive qualities of a woman, without all of her negative qualities. The narrator seems to believe that the young man is as beautiful as any woman, but is also more faithful and less fickle. Kolin also argues that, “numerous, though overlooked, sexual puns run throughout this indelicate panegyric to Shakespeare’s youthful friend.”[4] He suggests the reference to the youth’s eyes, which gild the objects upon which they gaze, may also be a pun on “gelding…The feminine beauty of this masculine paragon not only enhances those in his sight but, with the sexual meaning before us, gelds those male admirers who temporarily fall under the sway of the feminine grace and pulchritude housed in his manly frame.”[4]

Amy Stackhouse suggests an interesting interpretation of the form of sonnet 20. Stackhouse explains that the form of the sonnet (written in iambic pentameter with an extra-unstressed syllable on each line) lends itself to the idea of a “gender-bending” model. The unstressed syllable is a feminine rhyme, yet the addition of the syllable to the traditional form may also represent a phallus.[5] Sonnet 20 is one of only two in the sequence with feminine endings to its lines; the other is Sonnet 87.[6] Stackhouse also comments on the reveal of the gender of the addressee in the final few lines as a way of Shakespeare playing with the idea of gender throughout the poem. Stackhouse’s analysis of the nature aspect also seemed to play into the “gender-bending” model by creating this idea of Mother Nature falling in love with her creation and thus imparting a phallus to him. Which is represented in the extra-unstressed syllable as well.[5]

This idea of nature is also reflected in Philip C. Kolin’s analysis of the last part of the poem as well. Kolin’s observation of Shakespeare’s discussion of the man being for “women’s pleasure” does not lend itself to this idea of bisexuality or gender-bending at all. This is where Shakespeare is clearly saying that this is not homosexual love. Kolin is saying that nature made him for “women’s pleasure” and that is what is “natural”.[4] Kolin goes on to say that the phrase “to my purpose nothing” also reflects this natural aspect of being created for women’s pleasure. In this, however, he takes no account of Shakespeare's common pun of "nothing" ("O") to mean vagina.[7] Whereas Stackhouse would argue the poem is almost gender neutral, Kolin would argue that the poem is “playful” and “sexually (dualistic)”[4]

Notes

- 1 2 William Nelles, "Sexing Shakespeare’s Sonnets: Reading Beyond Sonnet 20," English Literary Renaissance Volume 39, Issue 1, February 2009: 128-140. Abstract

- ↑ Charles, Casey. "Was Shakespeare gay? Sonnet 20 and the politics of pedagogy." College Literature 25.3 (1998): 35-52. EBSCOhost. Web. 10 Nov. 2009.

- ↑ Charles, Casey. "Was Shakespeare gay? Sonnet 20 and the politics of pedagogy." College Literature 25.3 (1998): 35-52. EbSCOhost. Web. 10 Nov. 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Kolin, Philip C. "Shakespeare's Sonnet 20." Explicitor 45.1 (1986): 10-12. Print.

- 1 2 Stackhouse, Amy D. "Shakespeare's Half-Foot: Gendered Prosody in Sonnet 20." Explicitor 65 (2006): 202-04. Print.

- ↑ Larsen, Kenneth J. "Sonnet 20". Essays on Shakespeare's Sonnets. Retrieved 30 November 2014.

- ↑ Williams, Gordon (1997). "nothing". Shakespeare's Sexual Language: A Glossary. London: Athlone Press. p. 219. ISBN 0-8264-9134-0.

References

- Alden, Raymond (1916). The Sonnets of Shakespeare, with Variorum Reading and Commentary. Houghton-Mifflin, Boston.

- Baldwin, T. W. (1950). On the Literary Genetics of Shakspeare's Sonnets. University of Illinois Press, Urbana.

- Booth, Stephen (1977). Shakespeare's Sonnets. Yale University Press, New Haven.

- Dowden, Edward (1881). Shakespeare's Sonnets. London.

- Evans, G. Blakemore, Anthony Hecht, (1996). Shakespeare's Sonnets. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- Hubler, Edwin (1952). The Sense of Shakespeare's Sonnets. Princeton University Press, Princeton.

- Schoenfeldt, Michael (2007). The Sonnets: The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare’s Poetry. Patrick Cheney, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- Tyler, Thomas (1989). Shakespeare’s Sonnets. London D. Nutt.

- Vendler, Helen (1997). The Art of Shakespeare's Sonnets. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

External links

Works related to Sonnet 20 (Shakespeare) at Wikisource

Works related to Sonnet 20 (Shakespeare) at Wikisource- Paraphrase and analysis (Shakespeare-online)

- Analysis

| ||||||||||

.png)